Korean J Crit Care Med.

2017 Aug;32(3):231-239. 10.4266/kjccm.2017.00024.

Rapid Response Systems Reduce In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Arrest: A Pilot Study and Motivation for a Nationwide Survey

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea. jymoon@cnuh.co.kr

- 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea.

- 3Division of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Emergency Medicine, Hallym University Medical Center, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea.

- 5Division of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea.

- 6Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea.

- 7Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Dong-A University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 9Division of Pulmonology and Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, Korea.

- 10Division of Pulmonology and Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Dankook University Hospital, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea.

- 11Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea.

- 12Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic University of Daegu School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea.

- 13Division of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

- 14Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 15Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2391182

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2017.00024

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Early recognition of the signs and symptoms of clinical deterioration could diminish the incidence of cardiopulmonary arrest. The present study investigates outcomes with respect to cardiopulmonary arrest rates in institutions with and without rapid response systems (RRSs) and the current level of cardiopulmonary arrest rate in tertiary hospitals.

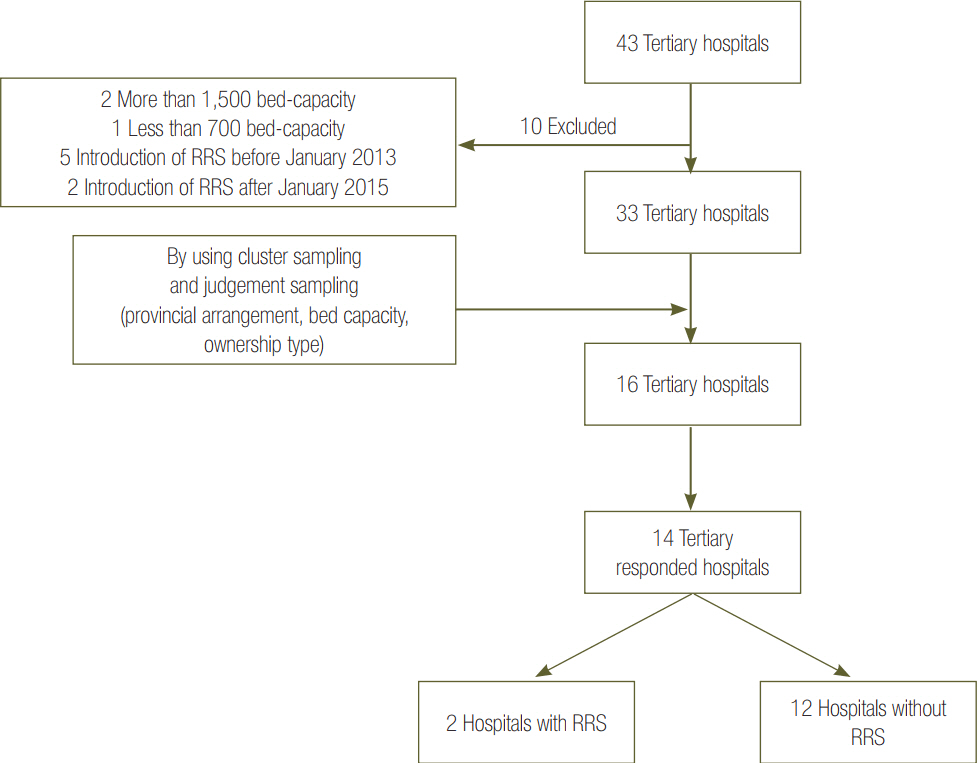

METHODS

This was a retrospective study based on data from 14 tertiary hospitals. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) rate reports were obtained from each hospital to include the number of cardiopulmonary arrest events in adult patients in the general ward, the annual adult admission statistics, and the structure of the RRS if present.

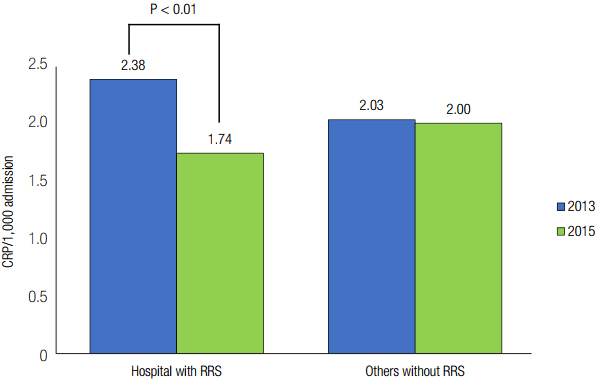

RESULTS

Hospitals with RRSs showed a statistically significant reduction of the CPR rate between 2013 and 2015 (odds ratio [OR], 0.731; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.577 to 0.927; P = 0.009). Nevertheless, CPR rates of 2013 and 2015 did not change in hospitals without RRS (OR, 0.988; 95% CI, 0.868 to 1.124; P = 0.854). National university-affiliated hospitals showed less cardiopulmonary arrest rate than private university-affiliated in 2015 (1.92 vs. 2.40; OR, 0.800; 95% CI, 0.702 to 0.912; P = 0.001). High-volume hospitals showed lower cardiopulmonary arrest rates compared with medium-volume hospitals in 2013 (1.76 vs. 2.63; OR, 0.667; 95% CI, 0.577 to 0.772; P < 0.001) and in 2015 (1.55 vs. 3.20; OR, 0.485; 95% CI, 0.428 to 0.550; P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

RRSs may be a feasible option to reduce the CPR rate. The discrepancy in cardiopulmonary arrest rates suggests further research should include a nationwide survey to tease out factors involved in in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest and differences in outcomes based on hospital characteristics.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Intensivists' Direct Management without Residents May Improve the Survival Rate Compared to High-Intensity Intensivist Staffing in Academic Intensive Care Units: Retrospective and Crossover Study Design

Jin Hyoung Kim, Jihye Kim, SooHyun Bae, Taehoon Lee, Jong-Joon Ahn, Byung Ju Kang

J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(3):. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e19.Rapid response systems in Korea

Bo Young Lee, Sang-Bum Hong

Acute Crit Care. 2019;34(2):108-116. doi: 10.4266/acc.2019.00535.

Reference

-

References

1. Morrison LJ, Neumar RW, Zimmerman JL, Link MS, Newby LK, McMullan PW Jr, et al. Strategies for improving survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States: 2013 consensus recommendations--a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013; 127:1538–63.2. Skrifvars MB, Nurmi J, Ikola K, Saarinen K, Castrén M. Reduced survival following resuscitation in patients with documented clinically abnormal observations prior to in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2006; 70:215–22.

Article3. Sandroni C, Nolan J, Cavallaro F, Antonelli M. Inhospital cardiac arrest: incidence, prognosis and possible measures to improve survival. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33:237–45.

Article4. Hillman KM, Bristow PJ, Chey T, Daffurn K, Jacques T, Norman SL, et al. Antecedents to hospital deaths. Intern Med J. 2001; 31:343–8.

Article5. Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002; 324:387–90.

Article6. Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M, Ruben BH, Sprung CL. Clinical antecedents to in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Chest. 1990; 98:1388–92.

Article7. Chen J, Ou L, Hillman K, Flabouris A, Bellomo R, Hollis SJ, et al. The impact of implementing a rapid response system: a comparison of cardiopulmonary arrests and mortality among four teaching hospitals in Australia. Resuscitation. 2014; 85:1275–81.

Article8. Chen J, Ou L, Hillman KM, Flabouris A, Bellomo R, Hollis SJ, et al. Cardiopulmonary arrest and mortality trends, and their association with rapid response system expansion. Med J Aust. 2014; 201:167–70.

Article9. Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, Berg RA, Billi JE, Bossaert L, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries. A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the international liaison committee on resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa). Resuscitation. 2004; 63:233–49.10. Thomas JW, Hofer TP. Accuracy of risk-adjusted mortality rate as a measure of hospital quality of care. Med Care. 1999; 37:83–92.

Article11. Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Identifying poor-quality hospitals: can hospital mortality rates detect quality problems for medical diagnoses? Med Care. 1996; 34:737–53.12. Zalkind DL, Eastaugh SR. Mortality rates as an indicator of hospital quality. J Healthc Manag. 1997; 42:3–15.13. DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL, et al. Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004; 13:251–4.

Article14. Goldhill DR, Worthington L, Mulcahy A, Tarling M, Sumner A. The patient-at-risk team: identifying and managing seriously ill ward patients. Anaesthesia. 1999; 54:853–60.

Article15. Winters BD, Weaver SJ, Pfoh ER, Yang T, Pham JC, Dy SM. Rapid-response systems as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 158(5 Pt 2):417–25.16. Maharaj R, Raffaele I, Wendon J. Rapid response systems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015; 19:254.

Article17. Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK, Berg RA, Sasson C. Rapid response teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170:18–26.18. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, Buckmaster J, Hart GK, Opdam H, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003; 179:283–7.

Article19. Direkze S, Jain S. Time to intervene? Lessons from the NCEPOD cardiopulmonary resuscitation report 2012. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2012; 73:585–7.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Prospective Study of the Epidemiology of Out-of-Hospital Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Arrest

- Rapid response systems in Korea

- Early Experience of Medical Alert System in a Rural Training Hospital: a Pilot Study

- Current Status of CPR in Korea

- Effects of a Rapid Response Team on the Clinical Outcomes of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation of Patients Hospitalized in General Wards