J Korean Med Sci.

2015 Dec;30(12):1847-1855. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.12.1847.

Cerebral Angiographic Findings of Cosmetic Facial Filler-related Ophthalmic and Retinal Artery Occlusion

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea. sejoon1@snu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, Hallym University College of Medicine, Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Radiology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- KMID: 2359971

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.12.1847

Abstract

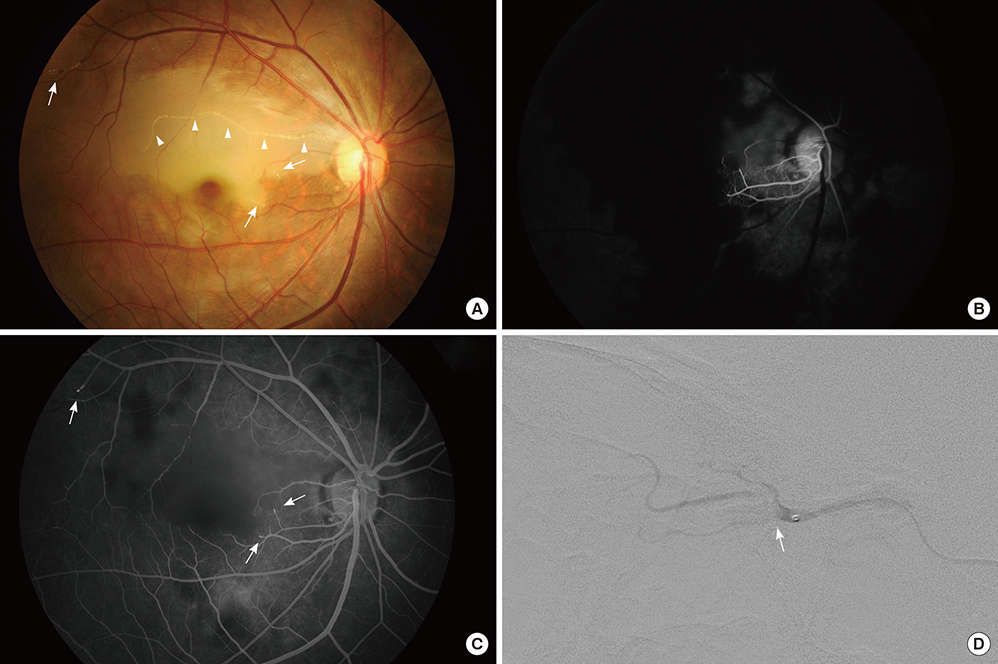

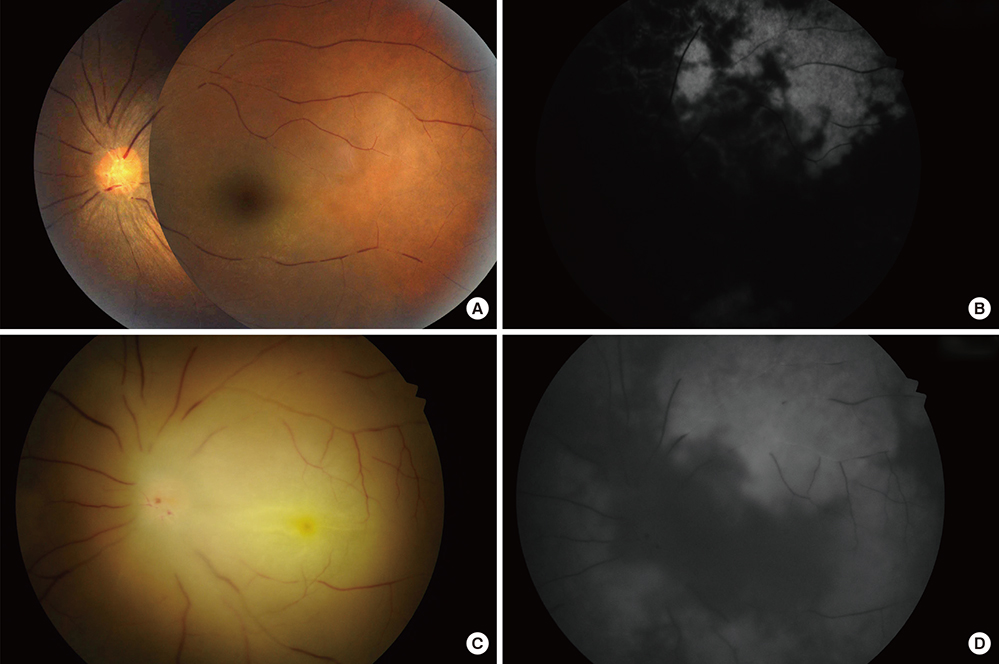

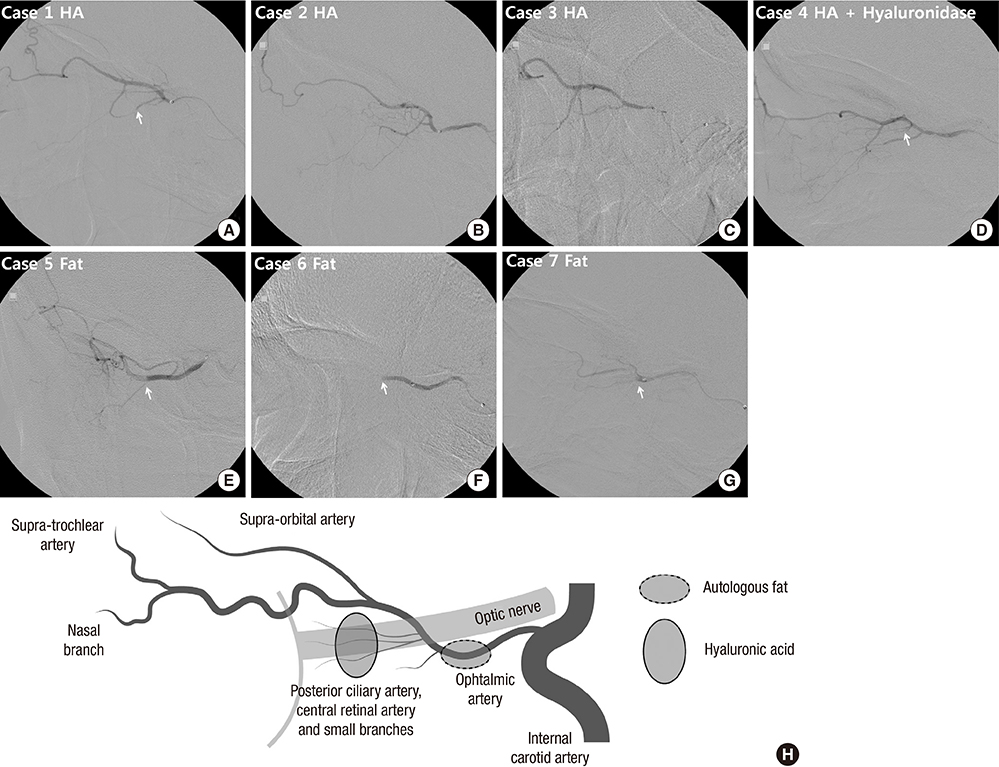

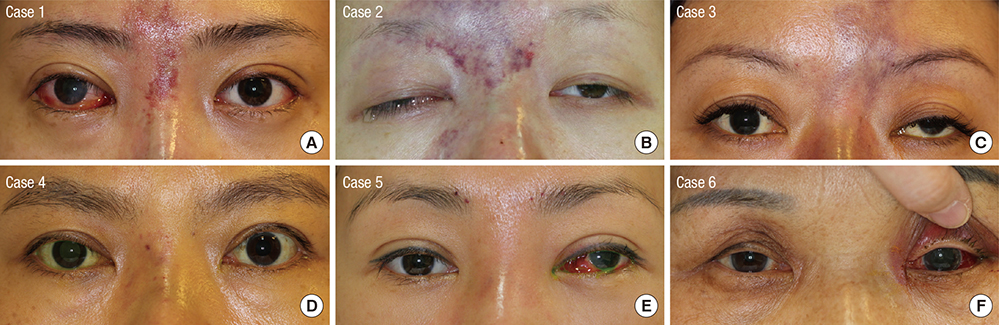

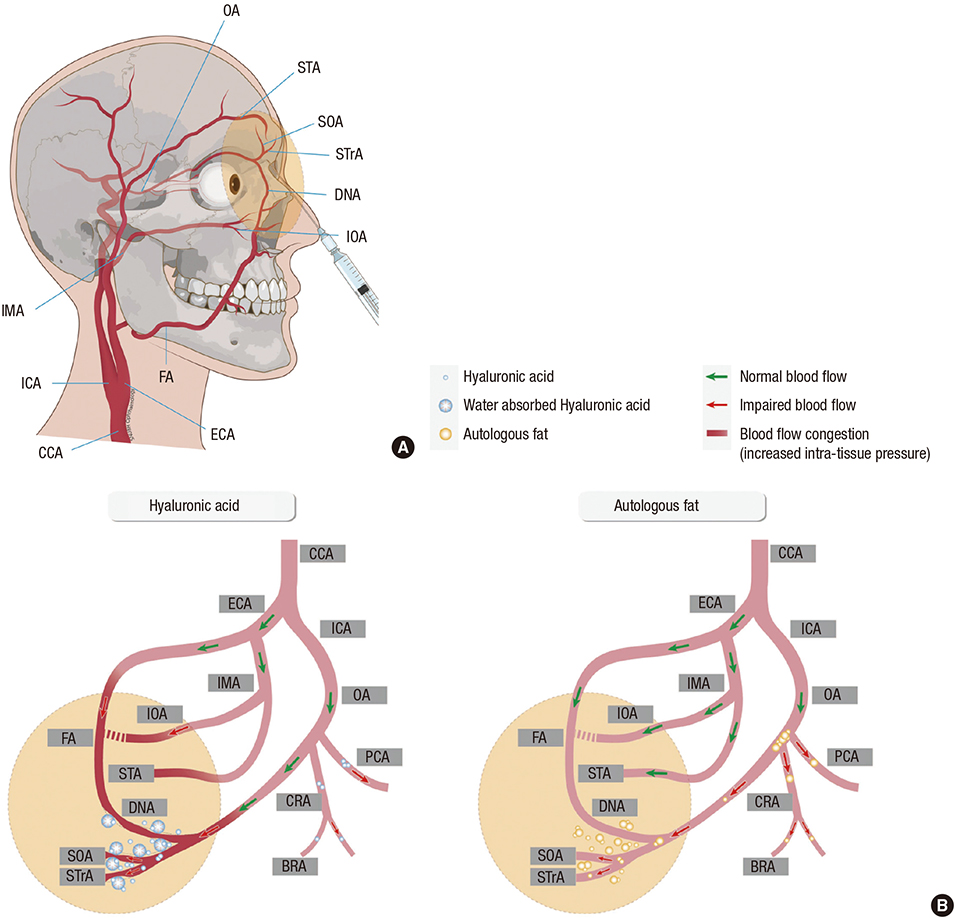

- Cosmetic facial filler-related ophthalmic artery occlusion is rare but is a devastating complication, while the exact pathophysiology is still elusive. Cerebral angiography provides more detailed information on blood flow of ophthalmic artery as well as surrounding orbital area which cannot be covered by fundus fluorescein angiography. This study aimed to evaluate cerebral angiographic features of cosmetic facial filler-related ophthalmic artery occlusion patients. We retrospectively reviewed cerebral angiography of 7 patients (4 hyaluronic acid [HA] and 3 autologous fat-injected cases) showing ophthalmic artery and its branches occlusion after cosmetic facial filler injections, and underwent intra-arterial thrombolysis. On selective ophthalmic artery angiograms, all fat-injected patients showed a large filling defect on the proximal ophthalmic artery, whereas the HA-injected patients showed occlusion of the distal branches of the ophthalmic artery. Three HA-injected patients revealed diminished distal runoff of the internal maxillary and facial arteries, which clinically corresponded with skin necrosis. However, all fat-injected patients and one HA-injected patient who were immediately treated with subcutaneous hyaluronidase injection showed preserved distal runoff of the internal maxillary and facial arteries and mild skin problems. The size difference between injected materials seems to be associated with different angiographic findings. Autologous fat is more prone to obstruct proximal part of ophthalmic artery, whereas HA obstructs distal branches. In addition, hydrophilic and volume-expansion property of HA might exacerbate blood flow on injected area, which is also related to skin necrosis. Intra-arterial thrombolysis has a limited role in reconstituting blood flow or regaining vision in cosmetic facial filler-associated ophthalmic artery occlusions.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adipose Tissue/transplantation

Adult

Aged

Arterial Occlusive Diseases/*etiology/*radiography/therapy

Cerebral Angiography

Cosmetic Techniques/adverse effects

Dermal Fillers/administration & dosage/*adverse effects

Face

Female

Humans

Hyaluronic Acid/administration & dosage/adverse effects

Hyaluronoglucosaminidase/administration & dosage

Injections, Subcutaneous

Ophthalmic Artery/*radiography

Retinal Artery Occlusion/*etiology/*radiography/therapy

Retrospective Studies

Transplantation, Autologous/adverse effects

Young Adult

Dermal Fillers

Hyaluronic Acid

Hyaluronoglucosaminidase

Figure

Reference

-

1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2014 plastic surgery statistics report. accessed on 12 June 2015. Available at Http://www.Plasticsurgery.Org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics/2014-statistics.Html.2. Danesh-Meyer HV, Savino PJ, Sergott RC. Case reports and small case series: ocular and cerebral ischemia following facial injection of autologous fat. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119:777–778.3. Park SH, Sun HJ, Choi KS. Sudden unilateral visual loss after autologous fat injection into the nasolabial fold. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008; 2:679–683.4. Sung MS, Kim HG, Woo KI, Kim YD. Ocular ischemia and ischemic oculomotor nerve palsy after vascular embolization of injectable calcium hydroxylapatite filler. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 26:289–291.5. Kim YJ, Kim SS, Song WK, Lee SY, Yoon JS. Ocular ischemia with hypotony after injection of hyaluronic acid gel. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 27:e152–e155.6. Park SJ, Woo SJ, Park KH, Hwang JM, Hwang GJ, Jung C, Kwon OK. Partial recovery after intraarterial pharmacomechanical thrombolysis in ophthalmic artery occlusion following nasal autologous fat injection. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011; 22:251–254.7. Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, Nardi M, Pantaloni M, Lazzeri S. Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012; 129:995–1012.8. Park SW, Woo SJ, Park KH, Huh JW, Jung C, Kwon OK. Iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012; 154:653–662.e1.9. Oh BL, Jung C, Park KH, Hong YJ, Woo SJ. Therapeutic intra-arterial hyaluronidase infusion for ophthalmic artery occlusion following cosmetic facial filler (hyaluronic acid) injection. Neuroophthalmology. 2014; 38:39–43.10. Carle MV, Roe R, Novack R, Boyer DS. Cosmetic facial fillers and severe vision loss. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014; 132:637–639.11. Kim YK, Ryoo NK, Park KH. Occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injection. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015; 133:224–225.12. Park KH, Kim YK, Woo SJ, Kang SW, Lee WK, Choi KS, Kwak HW, Yoon IH, Huh K, Kim JW, et al. Iatrogenic occlusion of the ophthalmic artery after cosmetic facial filler injections: a national survey by the Korean Retina Society. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014; 132:714–723.13. Grunebaum LD, Bogdan Allemann I, Dayan S, Mandy S, Baumann L. The risk of alar necrosis associated with dermal filler injection. Dermatol Surg. 2009; 35:1635–1640.14. Dayan SH, Arkins JP, Mathison CC. Management of impending necrosis associated with soft tissue filler injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011; 10:1007–1012.15. Kim JE, Sykes JM. Hyaluronic acid fillers: history and overview. Facial Plast Surg. 2011; 27:523–528.16. Humphrey S, Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Clinical experience with 11,460 mL of a 20-mg/mL, smooth, highly cohesive, viscous hyaluronic acid filler. Dermatol Surg. 2015; 41:1060–1067.17. Cox SE, Adigun CG. Complications of injectable fillers and neurotoxins. Dermatol Ther. 2011; 24:524–536.18. Cavallini M, Gazzola R, Metalla M, Vaienti L. The role of hyaluronidase in the treatment of complications from hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2013; 33:1167–1174.19. Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL, Carruthers JD. Successful management of an unusual presentation of impending necrosis following a hyaluronic acid injection embolus and a proposed algorithm for management with hyaluronidase. Dermatol Surg. 2007; 33:357–360.20. Kim DW, Yoon ES, Ji YH, Park SH, Lee BI, Dhong ES. Vascular complications of hyaluronic acid fillers and the role of hyaluronidase in management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011; 64:1590–1595.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Multifocal Retinal and Ciliary Artery Occlusion with Submacular Hemorrhage Following Cosmetic Facial Filler Injection

- Incomplete Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

- Multiple Cerebral Infarctions with Neurological Symptoms and Ophthalmic Artery Occlusion after Filler Injection

- Successful Endovascular Thrombectomy in a Patient with Monocular Blindness Due to Thrombus of the Ophthalmic Artery Orifice

- A Case of Sudden Unilateral Visual Loss Following Injection of Filler into the Glabella