J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc.

2016 Aug;55(3):234-244. 10.4306/jknpa.2016.55.3.234.

Measurement of Depression in Breast Cancer Patients by Using a Mobile Application : A Feasibility and Reliability Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. shaman_korea@mac.com

- 2Department of Surgery, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. jongwonlee116@gmail.com

- KMID: 2351550

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2016.55.3.234

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

This study examined feasibility and reliability of a mobile application to measure depression in breast cancer patients.

METHODS

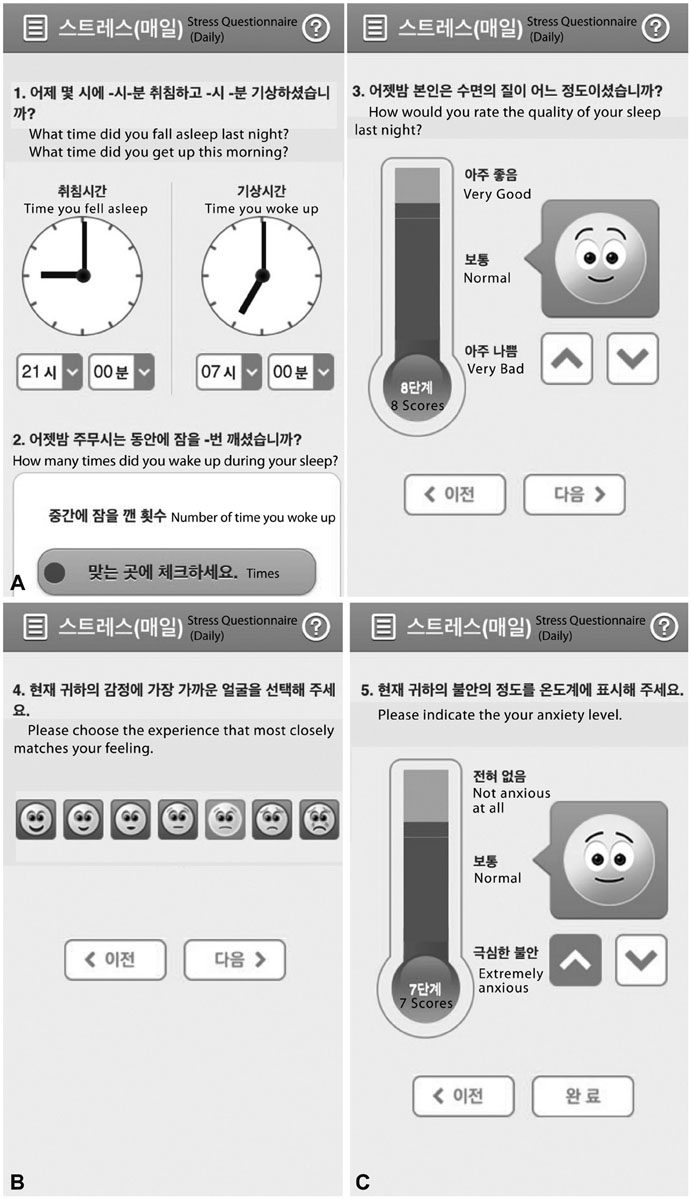

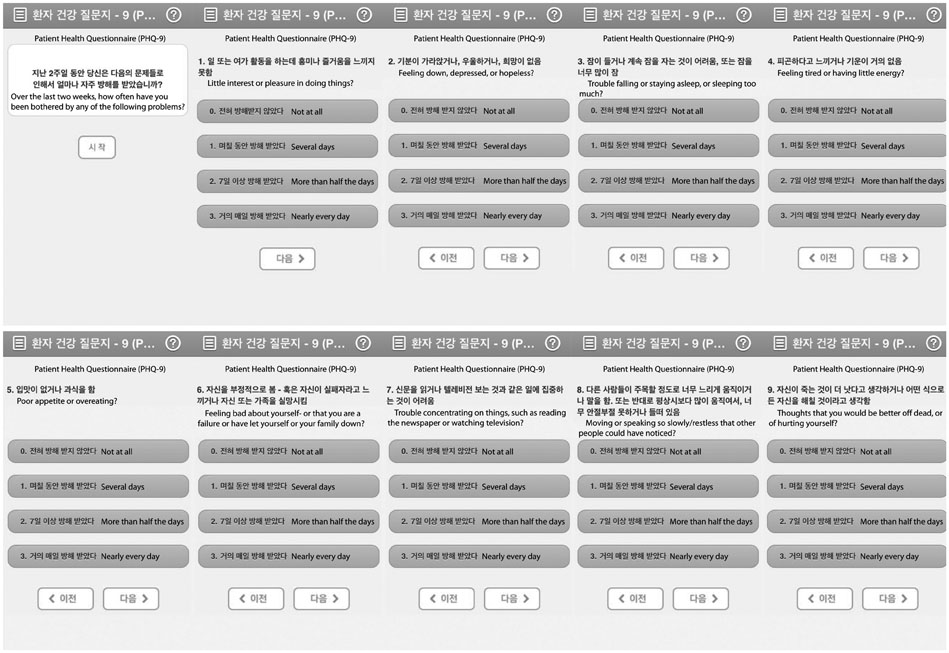

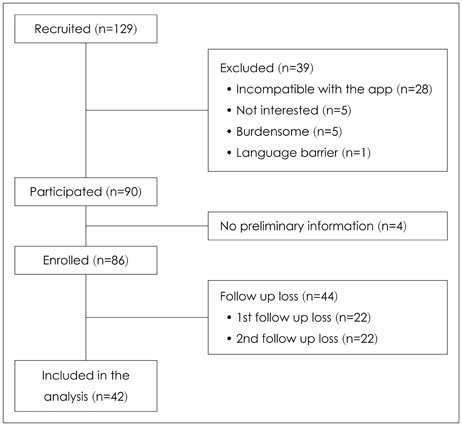

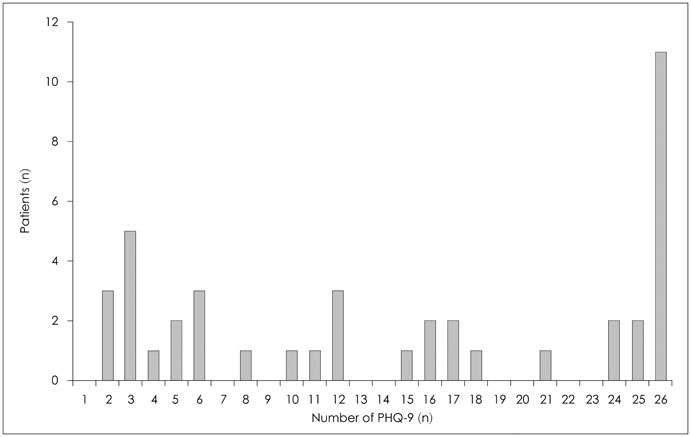

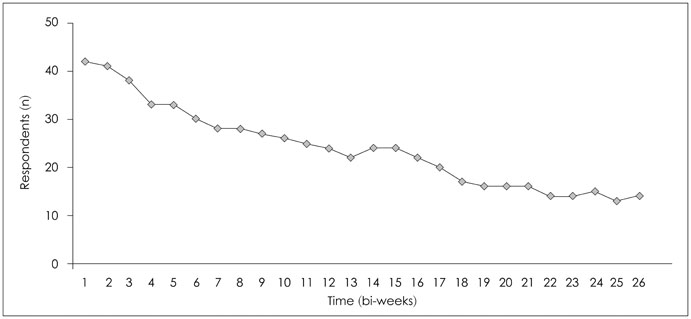

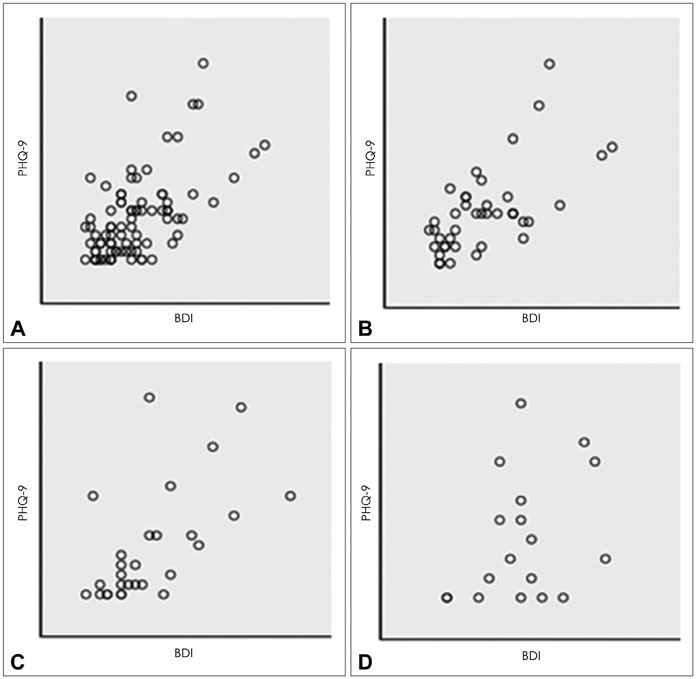

Forty-two breast cancer patients from the Department of Surgery at Asan Medical Center were included in the study. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), EuroQol Five Dimensional Questionnaire, and EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale were assessed at baseline and twice after surgery at regular intervals. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was delivered by as a push notification via mobile application every two weeks for 12 months. Feasibility was calculated using number of respondents and total number of PHQ-9 completed. Reliability was calculated from the relationship between PHQ-9 and BDI scores obtained within each two week period. Agreement between PHQ-9 and BDI scores in the diagnosis of depression was evaluated by kappa statistic and McNemar's test.

RESULTS

One thousand and ninety-two notifications for PHQ-9 were sent, and 622 responses were reported (compliance rate=57%). The compliance rate was not related to demographic factors except for the date of the first use of the application. Pearson's r between PHQ-9 and BDI scores was 0.599 (p<0.001), and kappa analysis demonstrated moderate level of agreement in diagnosis of depression (κ=0.431).

CONCLUSION

The compliance rate for patients reporting their symptoms by mobile application is high and the scores of PHQ-9 and BDI are correlated, which suggests that the mobile data measuring depression is reliable. However, this is a preliminary study and further study is needed to determine other factors that influence compliance rate.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Mobile Health for Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review

Bok Yae Chung, Eun Hee Oh, Su Jeong Song

Asian Oncol Nurs. 2017;17(3):133-142. doi: 10.5388/aon.2017.17.3.133.

Reference

-

1. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001; 10:19–28.

Article2. Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, Cowley D, Pepping M, Mc-Gregor BA, et al. Major depression after breast cancer: a review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008; 30:112–126.

Article3. Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, Riepma IC, de Bree R, Leemans CR, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014; 23:121–130.

Article4. Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005; 330:702.

Article5. Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum;2001. p. 405–413.6. Breitbart W, Jacobsen PB. Psychiatric symptom management in terminal care. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996; 12:329–347.

Article7. Hardman A, Maguire P, Crowther D. The recognition of psychiatric morbidity on a medical oncology ward. J Psychosom Res. 1989; 33:235–239.

Article8. Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Theobald DE, Edgerton S. Oncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998; 16:1594–1600.

Article9. Kroenke K, Taylor-Vaisey A, Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE. Interventions to improve provider diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care. A critical review of the literature. Psychosomatics. 2000; 41:39–52.

Article10. Brown KW, Levy AR, Rosberger Z, Edgar L. Psychological distress and cancer survival: a follow-up 10 years after diagnosis. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65:636–643.11. Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MA, Cleeland C, et al. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009; 10:865–871.

Article12. Watson M, Haviland JS, Greer S, Davidson J, Bliss JM. Influence of psychological response on survival in breast cancer: a populationbased cohort study. Lancet. 1999; 354:1331–1336.

Article13. Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, Rush R, Cargill A, Storey D, et al. Emotional distress in cancer patients: the Edinburgh Cancer Centre symptom study. Br J Cancer. 2007; 96:868–874.

Article14. Watson M, Homewood J, Haviland J, Bliss JM. Influence of psychological response on breast cancer survival: 10-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2005; 41:1710–1714.

Article15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006; 4:79.16. Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP. Patient-reported outcomes: a new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011; 2:137–144.

Article17. Chen H, Taichman DB, Doyle RL. Health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008; 5:623–630.

Article18. Ramachandran S, Lundy JJ, Coons SJ. Testing the measurement equivalence of paper and touch-screen versions of the EQ-5D visual analog scale (EQ VAS). Qual Life Res. 2008; 17:1117–1120.

Article19. Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient non-compliance with paper diaries. BMJ. 2002; 324:1193–1194.

Article20. Kauer SD, Reid SC, Crooke AH, Khor A, Hearps SJ, Jorm AF, et al. Self-monitoring using mobile phones in the early stages of adolescent depression: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012; 14:e67.

Article21. Morris ME, Kathawala Q, Leen TK, Gorenstein EE, Guilak F, Labhard M, et al. Mobile therapy: case study evaluations of a cell phone application for emotional self-awareness. J Med Internet Res. 2010; 12:e10.

Article22. International Telecommunication Union. Measuring the Information Society Report 2014. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union;2014.23. Digieco.co.kr [homepage on the Internet]. The mobile trend in the first half year of 2015. cited 2016 Mar 8. Available from: http://www.digieco.co.kr/KTFront/report/report_issue_trend_view.action?board_seq=10349&board_id=issue_trend#.24. Chan M, Estève D, Fourniols JY, Escriba C, Campo E. Smart wearable systems: current status and future challenges. Artif Intell Med. 2012; 56:137–156.

Article25. Pfeiffer PN, Bohnert KM, Zivin K, Yosef M, Valenstein M, Aikens JE, et al. Mobile health monitoring to characterize depression symptom trajectories in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2015; 174:281–286.

Article26. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961; 4:561–571.

Article27. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001; 33:337–343.28. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16:606–613.29. Park KB, Shin MS, Kim ZS. The cut-off score for the Korean version of Beck depression inventory. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1993; 12:71–81.30. Lee MK, Lee YH, Park SH, Sohn CH, Jung YJ, Hong SK, et al. A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory (I): Korean version (K-BDI): reliability land factor analysis. Korean J Psychopathol. 1995; 4:77–95.31. Nuevo R, Lehtinen V, Reyna-Liberato PM, Ayuso-Mateos JL. Usefulness of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening method for depression among the general population of Finland. Scand J Public Health. 2009; 37:28–34.

Article32. Hahn HM, Yum TH, Shin YW, Kim KH, Yoon DJ, Chung KJ. A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory in Korea. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1986; 25:487–500.33. Lee YK, Nam HS, Chuang LH, Kim KY, Yang HK, Kwon IS, et al. South Korean time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states: modeling with observed values for 101 health states. Value Health. 2009; 12:1187–1193.

Article34. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;1994.35. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a selfreport version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999; 282:1737–1744.

Article36. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012; 184:E191–E196.

Article37. Pettersson A, Boström KB, Gustavsson P, Ekselius L. Which instruments to support diagnosis of depression have sufficient accuracy? A systematic review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015; 69:497–508.

Article38. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33:159–174.

Article39. Schutt PE, Kung S, Clark MM, Koball AM, Grothe KB. Comparing the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression measures in an outpatient bariatric clinic. Obes Surg. 2016; 26:1274–1278.

Article40. Kung S, Alarcon RD, Williams MD, Poppe KA, Jo Moore M, Frye MA. Comparing the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression measures in an integrated mood disorders practice. J Affect Disord. 2013; 145:341–343.

Article41. BinDhim NF, Shaman AM, Trevena L, Basyouni MH, Pont LG, Alhawassi TM. Depression screening via a smartphone app: crosscountry user characteristics and feasibility. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015; 22:29–34.

Article42. Min YH, Lee JW, Shin YW, Jo MW, Sohn G, Lee JH, et al. Daily collection of self-reporting sleep disturbance data via a smartphone app in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014; 16:e135.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Application and evaluation of mobile nutrition management service for breast cancer patients

- Mobile Health for Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review

- The Reliability and Validity of World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (WHOQOL) in Patients with Breast Cancer: Physical Domain and Depression

- The development of a lifestyle modification mobile application, “Health for You” for overweight and obese breast cancer survivors in Korea

- Psychometric Properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Patients With Breast Cancer