Korean J Crit Care Med.

2014 Nov;29(4):250-256. 10.4266/kjccm.2014.29.4.250.

Implementing a Sepsis Resuscitation Bundle Improved Clinical Outcome: A Before-and-After Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. nswksj@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2227731

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2014.29.4.250

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Unlike other diseases, the management of sepsis has not been fully integrated in our daily practice. The aim of this study was to determine whether repeated training could improve compliance with a 6-h resuscitation bundle in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.

METHODS

Repeated education regarding a sepsis bundle was provided to the intensive care unit and emergency department residents, nurses, and faculties in a single university hospital. The educational program was led by a multidisciplinary team. A total of 175 adult patients with severe sepsis or septic shock were identified (88 before and 87 after the educational program). Hemodynamic resuscitation bundle and timely antibiotics administration were measured for all cases and mortality at 28 days after sepsis diagnosis was evaluated.

RESULTS

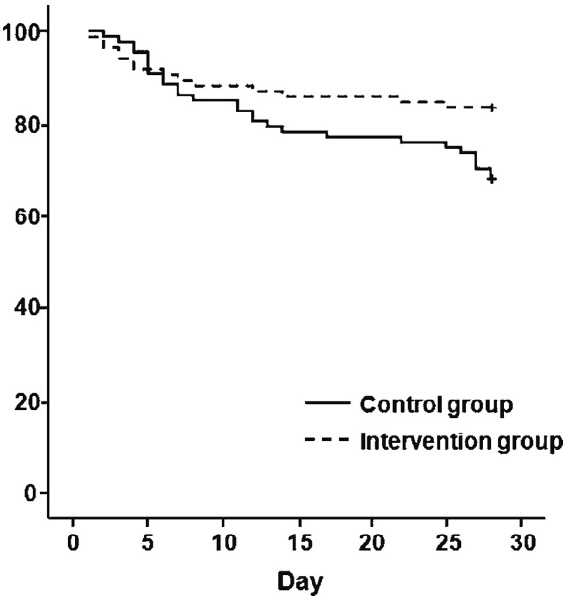

The compliance rate for the sepsis resuscitation bundle before the educational program was poor (0%), and repeated training improved it to 80% (p < 0.001). The 28-day mortality was significantly lower in the intervention group (16% vs. 32%, p = 0.040). Within the intervention group, patients for whom the resuscitation bundle was successfully completed had a significantly lower 28-day mortality than other patients (11% vs. 41%, p = 0.004).

CONCLUSIONS

Repeated education led by a multidisciplinary team and interdisciplinary communication improved the compliance rate of the 6-h resuscitation bundle in severe sepsis and septic shock patients. Compliance with the sepsis resuscitation bundle was associated with improved 28-day mortality in the study population.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1). Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J, Dellamonica P, Gouin F, Lepoutre A, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. A multicenter prospective study in intensive care units. French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. JAMA. 1995; 274:968–74.

Article2). Guidet B, Aegerter P, Gauzit R, Meshaka P, Dreyfuss D; CUB-Réa Study Group. Incidence and impact of organ dysfunctions associated with sepsis. Chest. 2005; 127:942–51.

Article3). Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41:580–637.

Article4). Gao F, Melody T, Daniels DF, Giles S, Fox S. The impact of compliance with 6-hour and 24-hour sepsis bundles on hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2005; 9:R764–70.5). Kortgen A, Niederprüm P, Bauer M. Implementation of an evidence-based “standard operating procedure” and outcome in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:943–9.

Article6). Micek ST, Roubinian N, Heuring T, Bode M, Williams J, Harrison C, et al. Before-after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:2707–13.

Article7). Nguyen HB, Corbett SW, Steele R, Banta J, Clark RT, Hayes SR, et al. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:1105–12.

Article8). Rivers E. Implementation of an evidence-based “standard operating procedure” and outcome in septic shock: what a sepsis pilot must consider before taking flight with your next patient. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:1247.

Article9). Trzeciak S, Dellinger RP, Abate NL, Cowan RM, Stauss M, Kilgannon JH, et al. Translating research to clinical practice: a 1-year experience with implementing early goal-directed therapy for septic shock in the emergency department. Chest. 2006; 129:225–32.10). Ferrer R, Artigas A, Levy MM, Blanco J, González-Díaz G, Garnacho-Montero J, et al. Improvement in process of care and outcome after a multicenter severe sepsis educational program in Spain. JAMA. 2008; 299:2294–303.

Article11). Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996; 22:707–10.12). Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. 1992. Chest. 2009; 136(5 Suppl):e28.13). Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:858–73.

Article14). De Miguel-Yanes JM, Andueza-Lillo JA, González-Ramallo VJ, Pastor L, Muñoz J. Failure to implement evidence-based clinical guidelines for sepsis at the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006; 24:553–9.

Article15). Chen YC, Chang SC, Pu C, Tang GJ. The impact of nationwide education program on clinical practice in sepsis care and mortality of severe sepsis: a population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e77414.

Article16). Paes BA, Modi A, Dunmore R. Changing physicians’ behavior using combined strategies and an evidence-based protocol. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994; 148:1277–80.

Article17). Gray J. Changing physician prescribing behaviour. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2006; 13:e81–4.18). Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999; 282:867–74.19). Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995; 274:700–5.

Article20). Shin HJ, Lee KH, Hwang SO, Kim H, Shin TY, Kim SC. The efficacy of early goal-directed therapy in septic shock patients in the emergency department: severe sepsis campaign. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2010; 25:61–70.

Article21). De Miguel-Yanes JM, Muñoz-González J, Andueza-Lillo JA, Moyano-Villaseca B, González-Ramallo VJ, Bustamante-Fermosel A. Implementation of a bundle of actions to improve adherence to the surviving sepsis campaign guidelines at the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27:668–74.

Article22). Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1368–77.

Article23). Lauzier F, Lévy B, Lamarre P, Lesur O. Vasopressin or norepinephrine in early hyperdynamic septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2006; 32:1782–9.24). Sharshar T, Blanchard A, Paillard M, Raphael JC, Gajdos P, Annane D. Circulating vasopressin levels in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2003; 31:1752–8.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Treatment of Severe Sepsis-Based on Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline

- Management of sepsis

- Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

- Update of Sepsis: Recent Evidences about Early Goal Directed Therapy

- Effects of a Case-Based Sepsis Education Program for General Ward Nurses on Knowledge, Accuracy of Sepsis Assessment, and Self-efficacy