J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2009 Oct;50(10):1475-1482. 10.3341/jkos.2009.50.10.1475.

The Effects of a Subtenoncapsular Injection of Bevacizumab for Ocular Surface Disease With Corneal Neovascularization

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. jck50ey@kornet.net

- KMID: 2212763

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2009.50.10.1475

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the effect of an injection of bevacizumab into the sub-Tenon's capsule on ocular surface neovascularization disease including pterygium and corneal neovascularization.

METHODS

Twenty-five eyes of 21 patients with pterygium and 19 eyes of 15 patients with corneal neovascularization were given an injection of 5 mg bevacizumab into the sub-Tenon's capsule. The clinical effects and complications were evaluated by analyzing the changes in anterior segment photo, visual acuity, and intraocular pressure at week one, week two, week four, and every month thereafter.

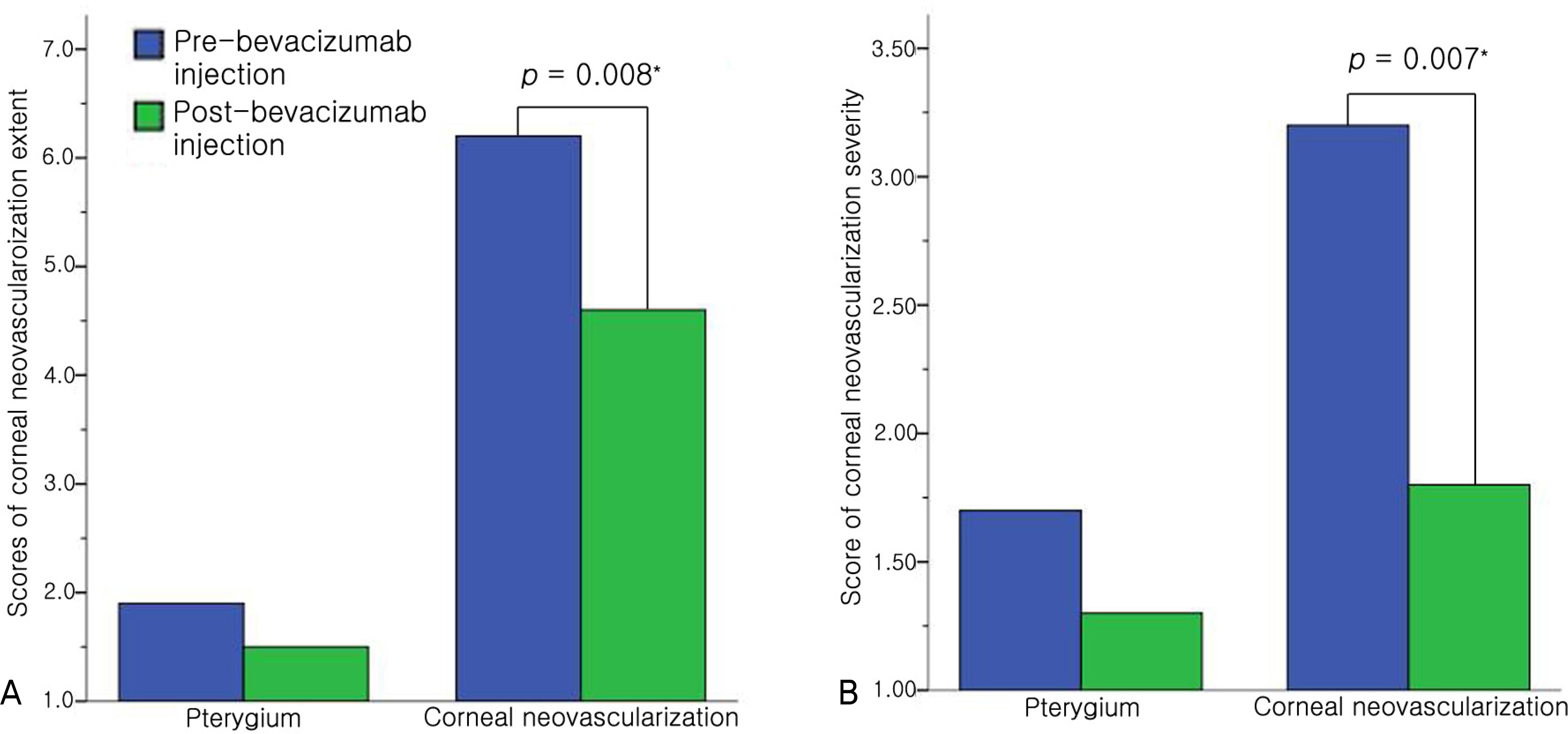

RESULTS

After injections of bevacizumab, partial remission of corneal neovascularized lesion was observed in five eyes (20%) of the pterygium group, and there were no significant changes in the visual acuity and no complications. In the corneal neovascularization group, corneal neovascularized lesions of 18 eyes (95%: 2 eyes, complete remission 16 eyes, partial remission) improved after injections of the bevacizumab and the scores of extent and severity of corneal neovascularized lesion improved significantly, unlike the pterygium group. The visual acuity of two eyes (11%) improved more than two lines of Yong-Han Jin's distance visual acuity test and there were no systemic side effects. Localized side effects included four eyes (21%) with punctate epithelial erosions and two eyes (11%) with temporary, elevated intraocular pressure in the corneal neovascularization group. The side effects improved without any additional treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

An injection of bevacizumab into the sub-Tenon's capsule is more effective in fresh lesions of corneal neovascularization disease than in old and stable lesions of pterygium. Therefore, it could be used as a prominent treatment of various corneal neovascularization diseases.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

The Effect of Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection before Conjunctival Autograft for Pterygium

Yong Il Kim, Geun Young Lee, Eun Joo Kim, Yeoun Hee Kim, Kyoo Won Lee, Young Jeung Park

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2015;56(6):847-855. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2015.56.6.847.Prognostic Factors Affecting Visual Recovery in Terson Syndrome with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Mi Sun Choi, Joo Hee Lee, Ji Hun Song, Yong Cheol Lim

J Neurocrit Care. 2017;10(2):99-106. doi: 10.18700/jnc.170026.

Reference

-

References

1. Folkman J, Ingber D. Inhibition of angiogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 1992; 3:89–96.2. Battegay EJ. Angiogenesis: mechanistic insights, neovascular diseases, and therapeutic prospects. J Mol Med. 1995; 73:333–46.

Article3. Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, et al. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983; 219:983–5.

Article4. De Vries C, Escobedo JA, Ueno H, et al. The fms-like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science. 1992; 255:989–91.5. Chen J, Liu W, Liu Z, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors (flt-1) in morbid human corneas and investigation of its clinic importance. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2002; 18:203–7.6. Philipp W, Speicher L, Humpel C. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in inflamed and vascularized human corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41:2514–22.7. Cursiefen C, Rummelt C, Küchle M. Immunohistochemical loca– lization of vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, and transforming growth factor beta1 in human corneas with neovascularization. Cornea. 2000; 19:526–33.8. Lazic R, Gabric N. Intravitreally administered bevacizumab (avastin) in minimally classic and occult choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007; 245:68–73.

Article9. Jorge R, Costa RA, Calucci D, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) for persistent new vessels in diabetic retonopathy (IBEPE study). Retina. 2006; 26:1006–13.10. Iliev ME, Domig D, Wolf-Schnurrbursch U, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) in the treatment of neovascular glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006; 142:1054–6.

Article11. Bahar I, Kaiserman I, McAllum P, et al. Subconjunctival bevacizu– mab injection for corneal neovascularization in recurrent pterygium. Curr Eye Res. 2008; 33:23–8.12. Uy HS, Chan PS, Ang RE. Topical bevacizumab and ocular surface neovascularization in patients with stevens-johnson syndrome. Cornea. 2008; 27:70–3.

Article13. Awadein A. Subconjunctival bevacizumab for vascularized rejected corneal grafts. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007; 33:1991–3.

Article14. Carrasco MA. Subconjunctival bevacizumab for corneal neovascu– larization in herpetic stromal keratitis. Cornea. 2008; 27:743–5.15. Bahar I, Kaiserman I, McAllum P, et al. Subconjunctival bevacizu– mab injection for corneal neovascularization. Cornea. 2008; 27:142–7.16. Lee JW, Park YJ, Kim IT, Lee KW. Clinical results after application of bevacizumab in recurrent pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008; 49:1901–9.

Article17. Hill JC, Maske R. Pathogenesis of pterygium. Eye. 1989; 3:218–26.

Article18. Zhang SX, Ma JX. Ocular neovascularization: implication of endogenous angiogenic inhibitors and potential therapy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007; 26:1–37.

Article19. Epstein RJ, Stulting RD, Hendricks RL, Harris DM. Corneal neo-vascularization. Pathogenesis and inhibition. Cornea. 1987; 6:250–7.20. Shimazaki J, Aiba M, Goto E, et al. Transplantation of human limbal stem epithelium cultivated on amniotic membrane for the treatment of severe ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:1285–90.21. Solomon A, Espana EM, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane trans– plantation for reconstruction of the conjunctival fornices. Ophthal– mology. 2003; 110:93–100.22. Nishida K, Yamato M, Hayashida Y, et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of autologous oral mucosal epithelium. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351:1170–2.

Article23. Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, et al. Transplantation of cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial cells in patients with severe ocular surface disorders. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004; 88:1280–4.

Article24. Tseng SC, Di Pascuale MA, Liu DT, et al. Intraoperative mitomycin C and amniotic membrane transplantation for fornix reconstruction in several cicatricial ocular surface diseases. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112:896–903.25. Hollick EJ, Watson SL, Dart JK, et al. Legeais BioKpro III keratoprosthesis implantation: long–term results in seven patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90:1146–51.26. Inatomi T, Nakamura T, Kojyo M, et al. Ocular surface recon– struction with combination of cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial transplantation and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006; 142:757–64.27. Santos MS, Gomes JA, Hofling-Lima AL, et al. Survival analysis of conjunctival limbal graftsand amniotic membrane transplantation in eyes with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005; 140:223–30.28. Geerling G, Liu CS, Collin JR, Dart JK. Costs and gains of complex procedures to rehabilitate end stage ocular surface disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86:1220–1.

Article29. Crum R, Szabo S, Folkman J. A new class of steroids inhibits angiogenesis in the presence of heparin or a heparin fragment. Science. 1985; 230:1375–8.

Article30. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101:1883–95.31. Cursiefen C, Chen L, Borges LP, et al. VEGF-A stimulates lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis in inflammatory neovascularization via macrophage recruitment. J Clin Invest. 2004; 113:1040–50.

Article32. Mimura T, Amano S, Usui T, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor C and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 in corneal lymphangiogenesis. Exp Eye Res. 2001; 72:71–8.

Article33. Singh D, Singh K. Transciliary filtration using the fugo blade TM. Ann Ophthalmol. 2002; 34:183–7.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Acute Visual Loss after Intravitreal Bevacizumab Injection in a Patient with Ocular Ischemic Syndrome

- Bi-weekly Subconjunctival Injection of Bevacizumab for Corneal Neovascularization after Burn Injury

- Ranibizumab Injection for Corneal Neovascularization Refractory to Bevacizumab Treatment

- The Effect of Bevacizumab on Corneal Neovascularization in Rabbits

- Two Cases of Corneal Neovascularization Improved by Electrocauterization and Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection