J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2009 Jan;50(1):139-144. 10.3341/jkos.2009.50.1.139.

Analysis of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Patients With Superior Segmental Optic Hypoplasia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, College of Medicine, Gyeonggi, Korea. eyechung90@hallym.or.kr

- KMID: 2211909

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2009.50.1.139

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To analyze the thickness of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in patients with superior segmental optic hypoplasia (SSOH) using optical coherence tomography (OCT).

METHODS

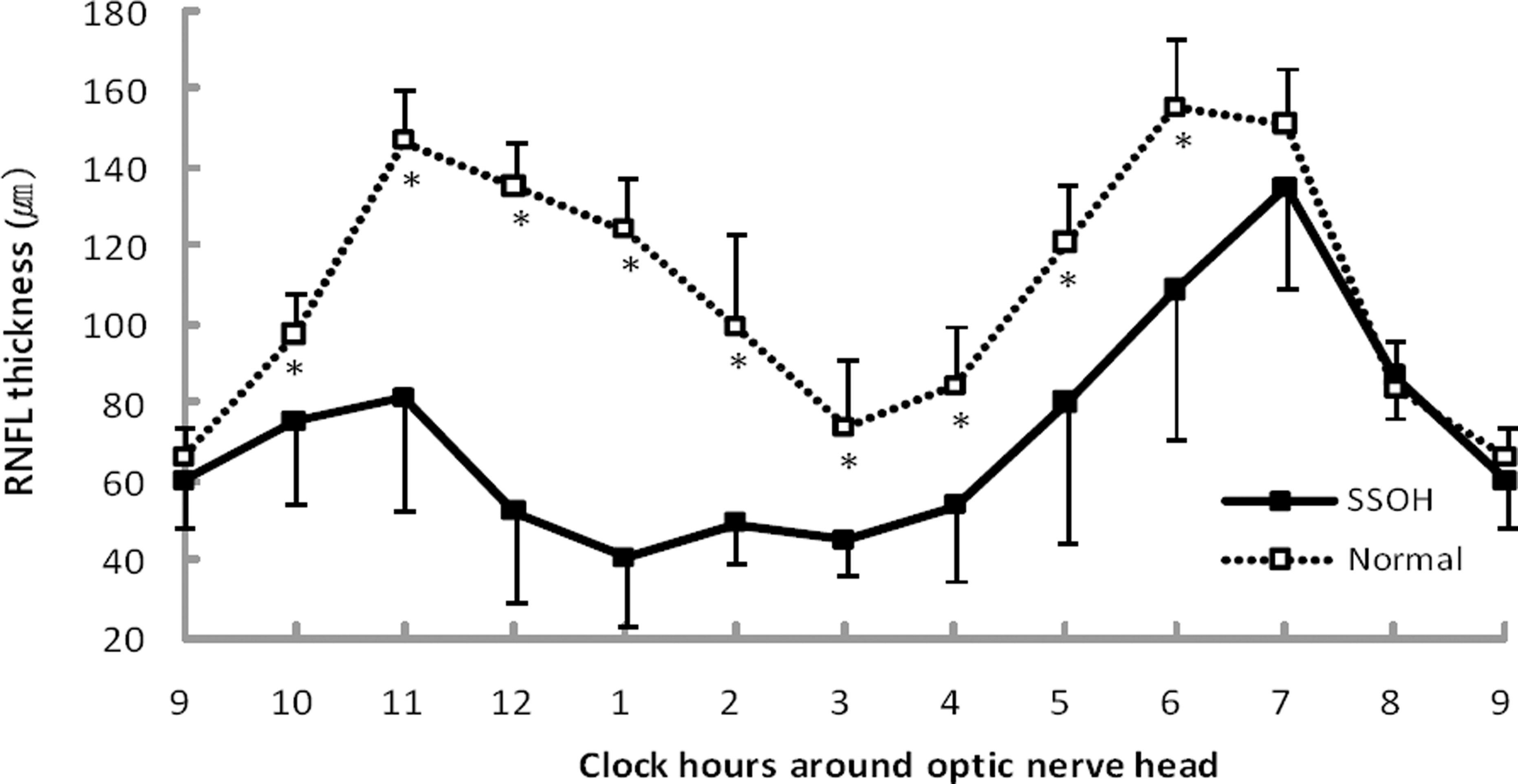

Ten eyes of 10 patients with SSOH and 20 eyes of 20 subjects as normal control were evaluated. The peripapillary RNFL thickness measured by Stratus OCT was compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

The mean RNFL thickness was significantly different between SSOH patients (72.35+/-14.77 micrometer) and normal subjects (111.61+/-6.62 micrometer) (p<0.001). The extent to which the RNFL thickness was below 5 percentile of normal subjects on the TSNIT graph was from the 41.7+/-15.53 to 110.1+/-7.47 scan number, which corresponded mainly with the superior nasal region. Moreover, in a clock-hour analysis, the peripapillary RNFL thic kness of the SSOH patients decreased significantly from 10 o'clock to 6 o'clock compared to normal subjects (p<0.01).

CONCLUSIONS

Peripapillary RNFL thickness in patients with SSOH was reduced in the superior, nasal, and inferior regions. Further studies involving larger populations of patients should be performed to verify these findings.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Analysis of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness of Superior Segmental Optic Hypoplasia and Normal-Tension Glaucoma

Joo Hyun Kim, Shin Hee Kang, Joo Hyun Park, Kayoung Yi

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013;54(2):331-337. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2013.54.2.331.

Reference

-

References

1. Kim RY, Hoyt WF, Lessell S, Narahara MH. Superior segmental optic hypoplasia. A sign of maternal diabetes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989; 107:1312–5.2. Landau K, Bajka JD, Kirchschläger BM. Topless optic disks in children of mothers with type I diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998; 125:605–11.

Article3. Provis JM, van Driel D, Billson FA, Russell P. Human fetal optic nerve: overproduction and elimination of retinal axons during development. J Comp Neurol. 1985; 238:92–100.

Article4. Brodsky MC, Shroeder GT, Ford R. Superior segmental optic hypoplasia in identical twins. J Clin Neuroophthamol. 1993; 13:152–4.5. Nelson M, Lessell S, Sadun AA. Optic nerve hypoplasia and maternal diabetes mellitus. Arch Neurol. 1986; 43:20–5.

Article6. Hashimoto M, Ohtsuka K, Nakagawa T, Hoyt WF. Topless optic disk syndrome without maternal diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999; 128:111–2.

Article7. Kim TW, Shin KC, Kim DM. Two cases of topless optic disc syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2000; 41:2291–5.8. Unoki K, Ohba N, Hoyt WF. Optical coherence tomography of superior segmental optic hypoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86:910–4.

Article9. Yamamoto T, Sato M, Iwase A. Superior segmental optic hypoplasia found in Tajimi Eye Health Care Project participants. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004; 48:578–83.

Article10. Petersen RA, Walton DS. Optic nerve hypoplasia with good visual acuity and visual field defects. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977; 95:254–8.

Article11. Bjork A, Laurell CG, Laurell U. Bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia with good visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978; 86:524–9.12. Miller NR. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. 6th. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;2005. p. 151–9.13. Garway-Heath DF, Poinoosawmy D, Fitzke FW, Hitchings RA. Mapping the visual field to the optic disc in normal tension glaucoma eyes. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107:1809–15.14. Birgbauer E, Cowan CA, Sretavan DW, Henkemeyer M. Kinase independent function of EphB receptors in retinal axon pathfinding to the optic disc from dorsal but not ventral retina. Development. 2000; 127:1231–41.

Article15. Brais P, Drance SM. The temporal field in chronic simple glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972; 88:518–22.

Article16. Kang JH, Kim DM. Seven cases of normal tension glaucoma with temporal visual field defect only. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002; 43:2175–8.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness of Superior Segmental Optic Hypoplasia and Normal-Tension Glaucoma

- Correlation between Visual Acuity and Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Optic Neuropathies

- Two Cases of Topless Optic Disc Syndrome

- Reproducibility of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness Evaluation by Nerve Fiber Analyzer

- The Parameters of the Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Measured with Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscope & Nerve Fiber Analyzer