J Korean Med Assoc.

2012 Oct;55(10):950-958. 10.5124/jkma.2012.55.10.950.

Current status and policy options for high-tech medical devices in Korea: vertical and horizontal synchronization of health policy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicien, Dankook University College of Medicien, Cheonan, Korea. leevan@dankook.ac.kr

- KMID: 2192815

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2012.55.10.950

Abstract

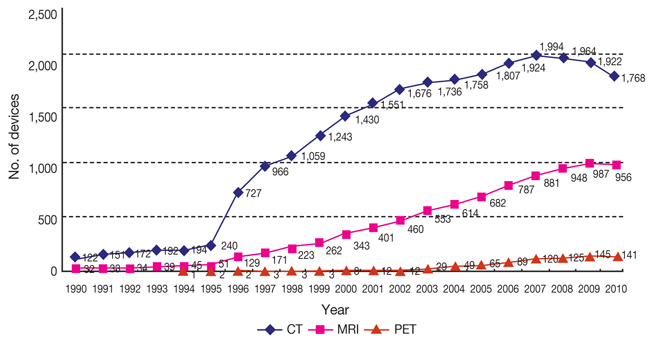

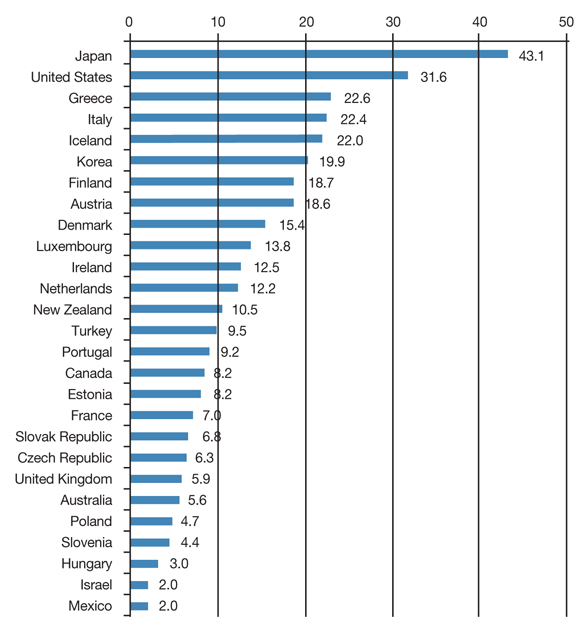

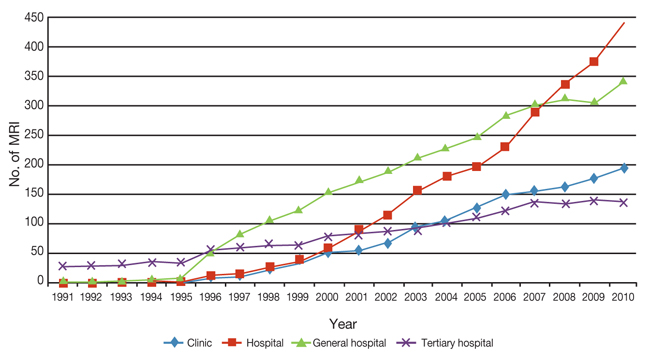

- This paper examines current status of high-tech medical devices in Korea, especially bringing focus to the computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, and traces government policies relevant to this situation. The rapid diffusion of high-tech medical devices mainly led by physician's clinics and small hospitals and lack of efficient policy coordination and synchronization have resulted deterioration of quality and decrease of social benefit. The quality problem could be resolved when the pursuit of micro-efficiencies by the providers are synchronized to the macro-efficiency of health system. If the government disclose quality information of high-tech devices and gives incentives to the provider's efforts to increase quality, the current competition between providers to capture patients could be evolved to the competition for better quality. In addition to this vertical synchronization, horizontal policy synchronizations such as with health insurance policy are also discussed.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The current status and directions of healthcare policy in Korea

Eun-Cheol Park

J Korean Med Assoc. 2012;55(10):930-931. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2012.55.10.930.

Reference

-

1. Ministry of Health and Welfare. New health plan 2020. 2011. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.2. Fuchs VR, Sox HC Jr. Physicians' views of the relative importance of thirty medical innovations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001. 20:30–42.

Article3. Goetghebeur MM, Forrest S, Hay JW. Understanding the underlying drivers of inpatient cost growth: a literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2003. 9(Spec No 1):SP3–SP12.4. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating valuebased competition on results. 2006. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.5. Cucic S. European Union health policy and its implications for national convergence. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000. 12:217–225.

Article6. Choi YJ, Cho SJ. Development of fee schedule for high-tech medical imaging devices. 2012. Seoul: Health Insurance Review Agency.7. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD health care resources [Internet]. cited 2012 Sep 17. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development;Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_REAC.8. Han KH, Ko SK, Jeong SH. High-price medical technologies in South Korea. Korean J Hosp Manage. 2007. 12:31–50.9. Oh YH, Kim JH. The demand and supply of major medical equipments and policy recommendations. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2007. 27:96–121.

Article10. National Conference of State Legislatures. Certificate of need: state health laws and programs [Internet]. 2011. cited 2012 Sep 20. Denver: National Conference of State Legislatures;Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/health/con-certificate-of-need-state-laws.aspx.11. Banta HD. US Office of Technology Assessment. Health care technology and its assessment in eight countries background paper. 1995. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.12. Cho JK. An improvement plan for health care delivery system. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2010. 169:6–15.13. Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006. 13:121–126.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Role of Academic Journal in Health Policy

- Public Health Policy and Health Equity

- Health Inequalities Policy in Korea: Current Status and Future Challenges

- A Conversaion with Senior Scholar; The History of the Korean Academy of Health Policy and Management and Future Tasks of Health Policy

- Expectations for the New Government’s Policy Innovation