J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg.

2015 Dec;17(4):324-330. 10.7461/jcen.2015.17.4.324.

Contrast Extravasation on Computed Tomography Angiography Imitating a Basilar Artery Trunk Aneurysm in Subsequent Conventional Angiogram-Negative Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Report of Two Cases with Different Clinical Courses

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Medical Research Institute, Pusan National University College of Medicine and Hospital, Busan, Korea. medifirst@pusan.ac.kr

- KMID: 2150971

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7461/jcen.2015.17.4.324

Abstract

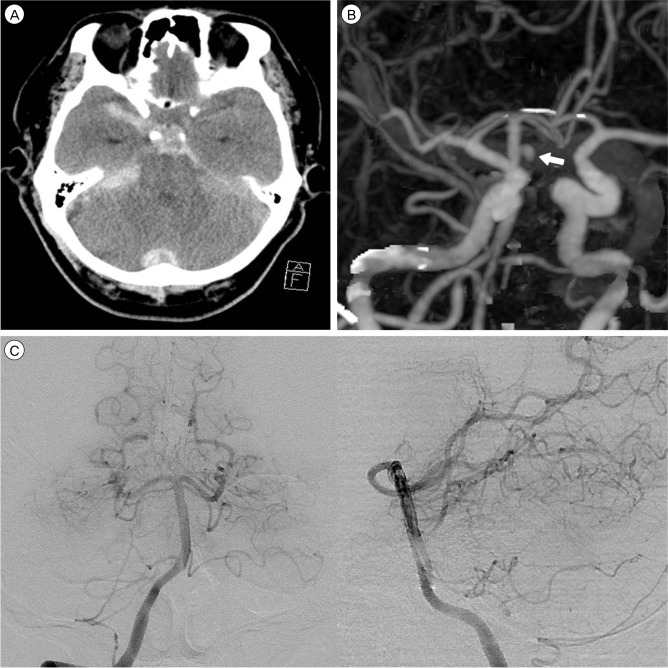

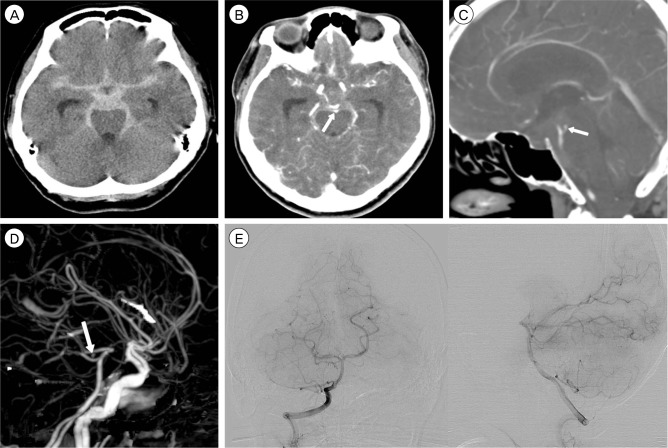

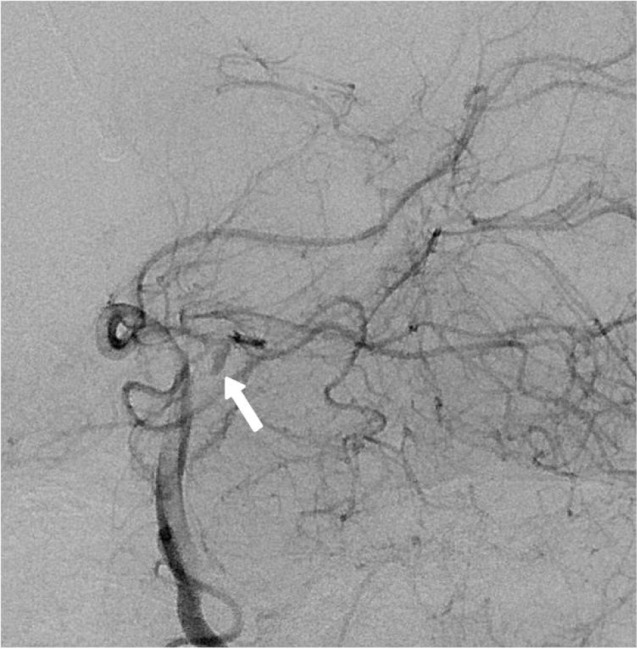

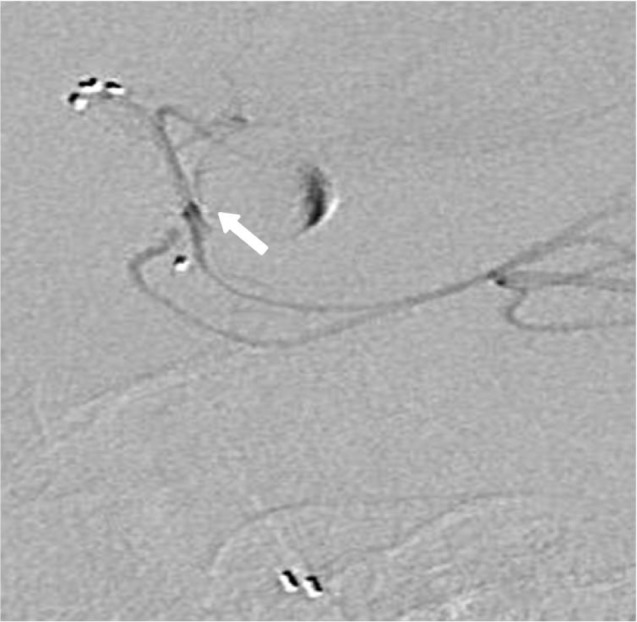

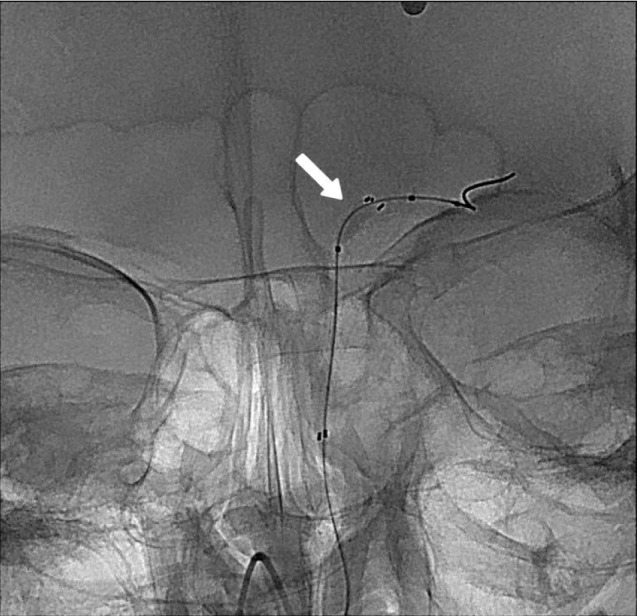

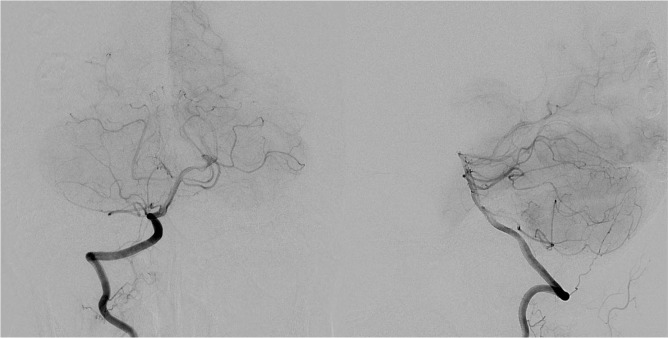

- Contrast extravasation on computed tomography angiography (CTA) is rare but becoming more common, with increasing use of CTA for various cerebral vascular diseases. We report on two cases of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in which the CTA showed an upper basilar trunk saccular lesion suggesting ruptured aneurysm. However, immediate subsequent digital subtraction angiography (DSA) failed to show a vascular lesion. In one case, repeated follow up DSA was also negative. The patient was treated conservatively and discharged without any neurologic deficit. In the other case, the patient showed sudden mental deterioration on the third hospital day and her brain CT showed rebleeding. The immediate follow up DSA showed contrast stagnation in the vicinity of the upper basilar artery, suggestive of pseudoaneurysm. Double stents deployment at the disease segment was performed. Due to the frequent use of CTA, contrast extravasation is an increasingly common observation. Physicians should be aware that basilar artery extravasation can mimic the appearance of an aneurysm.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Brisman JL, Song JK, Newell DW. Cerebral aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2006; 8. 31. 355(9):928–939. PMID: 16943405.

Article2. Cloft HJ, Joseph GJ, Dion JE. Risk of cerebral angiography in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral aneurysm, and arteriovenous malformation: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 1999; 2. 30(2):317–320. PMID: 9933266.3. Eskesen V, Sorensen EB, Rosenorn J, Schmidt K. The prognosis in subarachnoid hemorrhage of unknown etiology. J Neurosurg. 1984; 12. 61(6):1029–1031. PMID: 6502230.

Article4. Goddard AJ, Tan G, Becker J. Computed tomography angiography for the detection and characterization of intra-cranial aneurysms: current status. Clin Radiol. 2005; 12. 60(12):1221–1236. PMID: 16291304.

Article5. Inamasu J, Nakamura Y, Saito R, Horiguchi T, Kuroshima Y, Mayanagi K, et al. "Occult" ruptured cerebral aneurysms revealed by repeat angiography: result from a large retrospective study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2003; 12. 106(1):33–37. PMID: 14643914.

Article6. Juul R, Fredriksen TA, Ringkjob R. Prognosis in subarachnoid hemorrhage of unknown etiology. J Neurosurg. 1986; 3. 64(3):359–362. PMID: 3950713.

Article7. Nakatsuka M, Mizuno S, Uchida A. Extravasation on three-dimensional CT angiography in patients with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage and ruptured aneurysm. Neuroradiology. 2002; 1. 44(1):25–30. PMID: 11942496.

Article8. Ney JP. Midbrain stroke with angiogram-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage mimicking a perimesencephalic bleed. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005; May-Jun. 14(3):136–137. PMID: 17904013.

Article9. Ronkainen A, Hernesniemi J. Subarachnoid haemorrhage of unknown aetiology. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992; 119(1-4):29–34. PMID: 1481749.

Article10. Ryu CW, Kim SJ, Lee DH, Suh DC, Kwun BD. Extravasation of intracranial aneurysm during computed tomography angiography: mimicking a blood vessel. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005; Sep-Oct. 29(5):677–679. PMID: 16163041.11. Stetson ND, Pile-Spellman J, Brisman JL. Contrast extravasation on computed tomographic angiography mimicking a basilar artery aneurysm in angiogram-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage: report of 2 cases. Neurosurgery. 2012; 11. 71(5):E1047–E1052. discussion E1052PMID: 22806079.12. Tatter SB, Buonanno FS, Ogilvy CS. Acute lacunar stroke in association with angiogram-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage. Mechanistic implications of two cases. Stroke. 1995; 5. 26(5):891–895. PMID: 7740585.13. Wada R, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, Sahlas DJ, Gladstone DJ, Tomlinson G, et al. CT angiography "spot sign" predicts hematoma expansion in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007; 4. 38(4):1257–1262. PMID: 17322083.

Article14. Walker MT, Wattamwar A, Mellman D, Mo J. Active hemorrhage into a postresection cavity detected by neuro-CT angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005; 5. 26(5):1163–1165. PMID: 15891177.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Contrast Extravasation on Computed Tomography Angiography Imitating a Basilar Artery Trunk Aneurysm in Subsequent Conventional Angiogram-Negative Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Report of Two Cases with Different Clinical Courses

- Three-Dimensional Fusion Angiography of a Giant Basilar Aneurysm for Coil Embolization

- Incidental Discovery of Angiogram-negative Aneurysm during Aneurysm Surgery: Case Report

- Fatal Traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage due to Acute Rebleeding of a Pseudoaneurysm Arising from the Distal Basilar Artery

- Rupturing Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysm during Computed Tomography Angiography: Three-Dimensional Visualization of Bleeding into the Septum Pellucidum and the Lateral Ventricle