J Korean Med Sci.

2012 Oct;27(10):1208-1214. 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.10.1208.

Clinical Characteristics of an Esophageal Fish Bone Foreign Body from Chromis notata

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University School of Medicine, Jeju, Korea. kimhup@jejunu.ac.kr

- KMID: 1778828

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2012.27.10.1208

Abstract

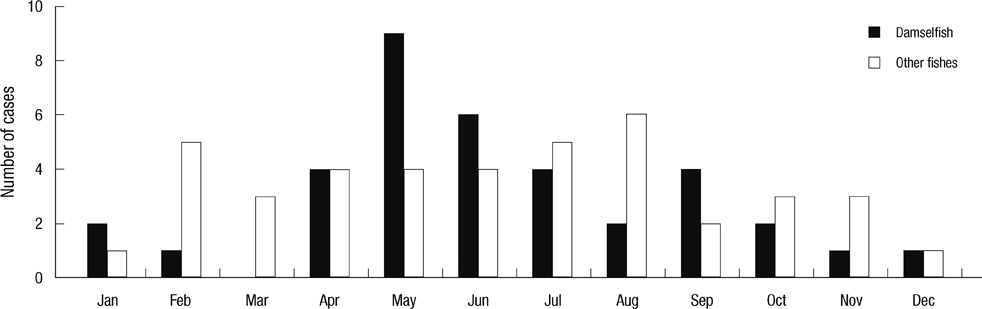

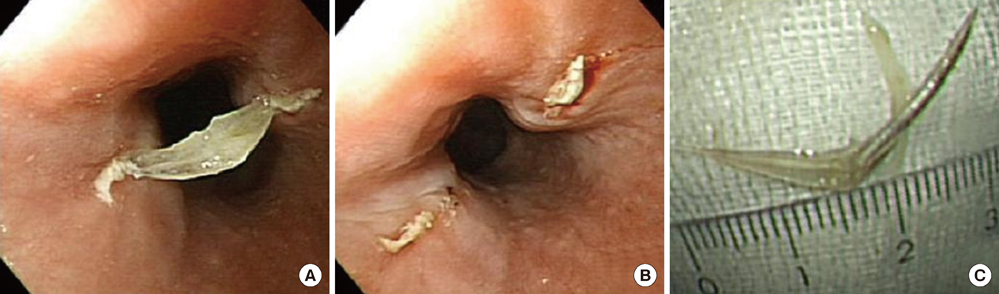

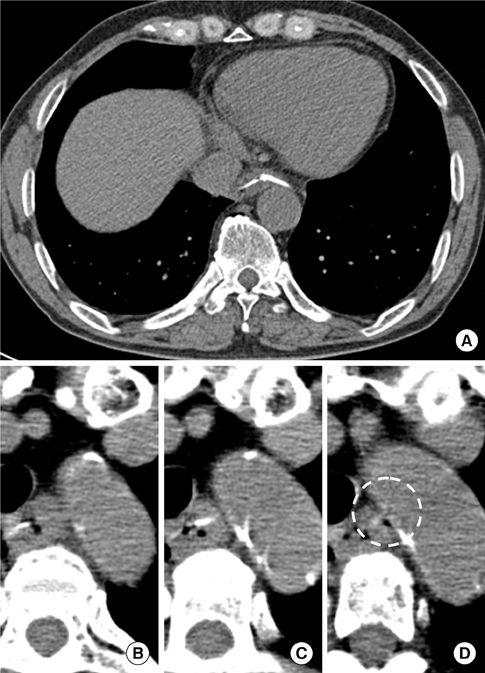

- Damselfish Chromis notata is a small fish less than 15 cm long and it is widespread in the Indo-Pacific Ocean. Of all the cases of fish bone foreign body (FBFB) disease at our hospital, a damselfish FBFB was very common, and a specific part of the bone complex was involved in the majority of cases. This study was performed to evaluate the clinical characteristics of damselfish FBFB in Jeju Island. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records from March 2004 to March 2011 for foreign body diseases. Among 126 cases of foreign body diseases, there were 77 (61.1%) cases of FBFB. The mean age +/- standard deviation was 57.8 +/- 12.7 yr, and this was higher in females 60.9 +/- 14.6 yr vs 54.1 +/- 8.7 yr. Damselfish was the most common origin of a FBFB 36 out of total 77 cases. The anal fin spine-pterygiophore complex of damselfish was most commonly involved and cause more severe clinical features than other fish bone foreign bodies; deep 2.7 +/- 0.8 cm vs 2.3 +/- 0.8 cm; P < 0.01, more common mural penetration 23/36 vs 10/41; P < 0.01, and longer hospital stay 12.6 +/- 20.0 days 4.7 +/- 4.8 days; P = 0.02. We recommend removing the anal fin spine-pterygiophore complex during cleaning the damselfish before cooking.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Guitron A, Adalid R, Huerta F, Macias M, Sanchez-Navarrete M, Nares J. Extraction of foreign bodies in the esophagus. Experience in 215 cases. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 1996. 61:19–26.2. Ngan JH, Fok PJ, Lai EC, Branicki FJ, Wong J. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion. Experience of 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990. 211:459–462.3. Nelson JS. Fishes of the World. 2006. 4th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.;393–394.4. Wu IS, Ho TL, Chang CC, Lee HS, Chen MK. Value of lateral neck radiography for ingested foreign bodies using the likelihood ratio. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008. 37:292–296.5. Ritchie T, Harvey M. The utility of plain radiography in assessment of upper aerodigestive tract fishbone impaction: an evaluation of 22 New Zealand fish species. N Z Med J. 2010. 123:32–37.6. Shihada R, Goldsher M, Sbait S, Luntz M. Three-dimensional computed tomography for detection and management of ingested foreign bodies. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009. 88:910–911.7. Luk WH, Fan WC, Chan RY, Chan SW, Tse KH, Chan JC. Foreign body ingestion: comparison of diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography versus endoscopy. J Laryngol Otol. 2009. 123:535–540.8. Scher RL, Tegtmeyer CJ, McLean WC. Vascular injury following foreign body perforation of the esophagus. Review of the literature and report of a case. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990. 99:698–702.9. Singh B, Kantu M, Har-El G, Lucente FE. Complications associated with 327 foreign bodies of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997. 106:301–304.10. Shimizu T, Marusawa H, Yamashita Y. Pneumothorax following esophageal perforation due to ingested fish bone. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010. 8:A24.11. Mukhopadhyay B, Tripathy BB, Saha S, Shukla RM, Saha SR. Acquired tracheo-oesophageal fistula: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc. 2008. 106:806. 808.12. Macchi V, Porzionato A, Bardini R, Parenti A, De Caro R. Rupture of ascending aorta secondary to esophageal perforation by fish bone. J Forensic Sci. 2008. 53:1181–1184.13. Blanco Ramos M, Rivo Vazquez JE, Garcia-Fontan E, Amoedo TO. Systemic air embolism in a patient with ingestion of a foreign body. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009. 8:292–294.14. Maseda E, Ablanedo A, Baldo C, Fernandez MJ. Migration and extrusion from the upper digestive tract to the skin of the neck of a foreign body (fish bone). Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2006. 57:474–476.15. Okafor BC. Aneurysm of the external carotid artery following a foreign body in the pharynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1978. 92:429–434.16. White RK, Morris DM. Diagnosis and management of esophageal perforations. Am Surg. 1992. 58:112–119.17. Sabiston DCJ, Lyerly HK. Textbook of Surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 1997. 15th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co..18. Katsetos MC, Tagbo AC, Lindberg MP, Rosson RS. Esophageal perforation and mediastinitis from fish bone ingestion. South Med J. 2003. 96:516–520.19. McCanse DE, Kurchin A, Hinshaw JR. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Am J Surg. 1981. 142:335–337.20. Nandi P, Ong GB. Foreign body in the oesophagus: review of 2394 cases. Br J Surg. 1978. 65:5–9.21. Skinner DB, Little AG, DeMeester TR. Management of esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 1980. 139:760–764.22. Michel L, Grillo HC, Malt RA. Operative and nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Ann Surg. 1981. 194:57–63.23. Wesdorp IC, Bartelsman JF, Huibregtse K, den Hartog Jager FC, Tytgat GN. Treatment of instrumental oesophageal perforation. Gut. 1984. 25:398–404.24. Radmark T, Sandberg N, Pettersson G. Instrumental perforation of the oesophagus. A ten year study from two ENT clinics. J Laryngol Otol. 1986. 100:461–465.25. Cameron JL, Kieffer RF, Hendrix TR, Mehigan DG, Baker RR. Selective nonoperative management of contained intrathoracic esophageal disruptions. Ann Thorac Surg. 1979. 27:404–408.26. Altorjay A, Kiss J, Voros A, Bohak A. Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Is it justified? Ann Surg. 1997. 225:415–421.27. Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, Marshall MB, Kaiser LR, Kucharczuk JC. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004. 77:1475–1483.28. Shaffer HA Jr, Valenzuela G, Mittal RK. Esophageal perforation. A reassessment of the criteria for choosing medical or surgical therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1992. 152:757–761.29. Brook I, Frazier EH. Microbiology of mediastinitis. Arch Intern Med. 1996. 156:333–336.30. George VL. Evans DH, Claiborne JB, editors. Locomotion. The physiology of fishes. 2006. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group;3–27.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of a Pharyngeal Impacted Fish Bone Foreign Body Detected by Finger Palpation

- Analysis of Clinical Feature and Management of Fish Bone Ingestion of Upper Gastrointestinal Tract

- Esophageal Foreign Body: Treatment and Complications

- Oroesophageal Fish Bone Foreign Body

- Small Bowel Perforation by a Fish Bone in Intestinal Obstruction: A Case Report