Yonsei Med J.

2011 Sep;52(5):701-716. 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.5.701.

Are You "Tilting at Windmills" or Undertaking a Valid Clinical Trial?

- Affiliations

-

- 1ICORD (International Collaboration On Repair Discoveries), University of British Columbia (UBC) and Vancouver Coastal Health, Blusson Spinal Cord Centre, Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, Canada. steeves@icord.org

- KMID: 1108061

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2011.52.5.701

Abstract

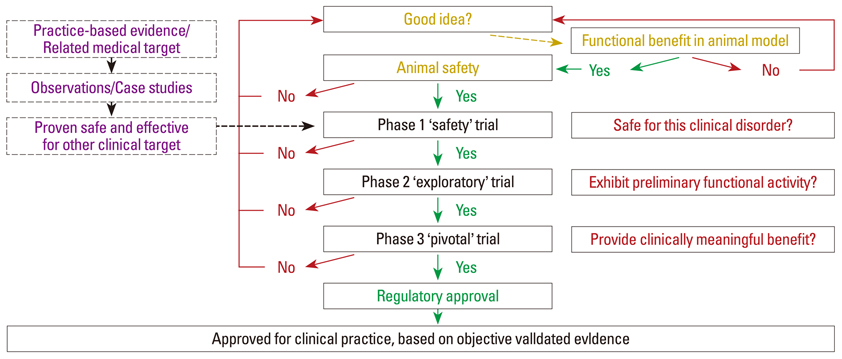

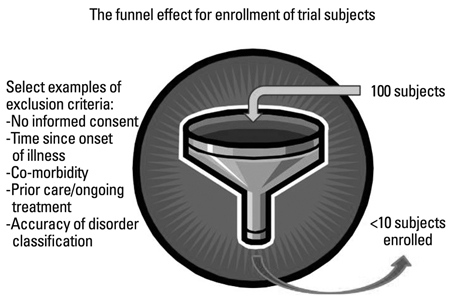

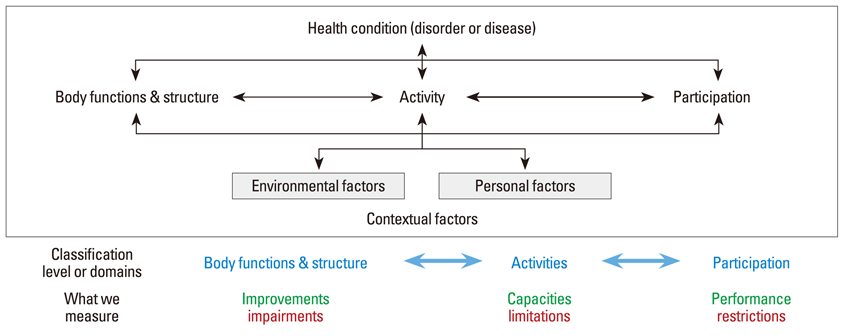

- In this review, several aspects surrounding the choice of a therapeutic intervention and the conduct of clinical trials are discussed. Some of the background for why human studies have evolved to their current state is also included. Specifically, the following questions have been addressed: 1) What criteria should be used to determine whether a scientific discovery or invention is worthy of translation to human application? 2) What recent scientific advance warrants a deeper understanding of clinical trials by everyone? 3) What are the different types and phases of a clinical trial? 4) What characteristics of a human disorder should be noted, tracked, or stratified for a clinical trial and what inclusion /exclusion criteria are important to enrolling appropriate trial subjects? 5) What are the different study designs that can be used in a clinical trial program? 6) What confounding factors can alter the accurate interpretation of clinical trial outcomes? 7) What are the success rates of clinical trials and what can we learn from previous clinical trials? 8) What are the essential principles for the conduct of valid clinical trials?

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bown SR. Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. 2004. New York: Thomas Dunne Books (St. Martin's Press).2. Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003. 327:1459–1461.

Article3. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008. 336:924–926.

Article4. Steeves JD. Lin VW, editor. Considerations for the Translation of Pre-Clinical Discoveries and the Conduct of Valid Spinal Cord injury Clinical Trials. Spinal Cord Medicine. 2010. 2nd ed. New York: Demos;930–938.5. Kwon BK, Okon EB, Tsai E, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, Magnuson DK, Reier PJ, et al. A Grading System To Evaluate Objectively the Strength of Pre-Clinical Data of Acute Neuroprotective Therapies for Clinical Translation in Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010. 10. 18. [Epub ahead of print].

Article6. Tetzlaff W, Okon EB, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Hill CE, Sparling JS, Plemel JR, et al. A systematic review of cellular transplantation therapies for spinal cord injury. J Neurotrama. 2010. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1177.

Article7. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006. 126:663–676.

Article8. Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007. 131:861–872.

Article9. Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007. 318:1917–1920.

Article10. Blight A, Curt A, Ditunno JF, Dobkin B, Ellaway P, Fawcett J, et al. Position statement on the sale of unproven cellular therapies for spinal cord injury: the international campaign for cures of spinal cord injury paralysis. Spinal Cord. 2009. 47:713–714.

Article11. Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2007. 45:190–205.

Article12. Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Tuszynski MH, Ditunno JF, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord. 2007. 45:206–221.

Article13. Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, Lammertse D, Kalichman M, Rask C, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP Panel: clinical trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord. 2007. 45:222–231.

Article14. Lammertse D, Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Rask C, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial design. Spinal Cord. 2007. 45:232–242.

Article15. Steeves JD, Kramer JK, Fawcett JW, Cragg J, Lammertse DP, Blight AR, et al. Extent of spontaneous motor recovery after traumatic cervical sensorimotor complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011. 49:257–265.

Article16. Zariffa J, Kramer JL, Fawcett JW, Lammertse DP, Blight AR, Guest J, et al. Characterization of neurological recovery following traumatic sensorimotor complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011. 49:463–471.

Article17. Illes J, Reimer JC, Kwon BK. Stem Cell Clinical Trials for Spinal Cord Injury: Readiness, Reluctance, Redefinition. Stem Cell Rev. 2011. 04. 08. [Epub ahead of print].

Article18. Donovan WH. Ethics, health care and spinal cord injury: research, practice and finance. Spinal Cord. 2011. 49:162–174.

Article19. Ziebland S, Featherstone K, Snowdon C, Barker K, Frost H, Fairbank J. Does it matter if clinicians recruiting for a trial don't understand what the trial is really about? Qualitative study of surgeons' experiences of participation in a pragmatic multicentre RCT. Trials. 2007. 8:4.

Article20. Gatchel RJ, Lurie JD, Mayer TG. Minimal clinically important difference. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010. 35:1739–1743.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Research Related Activities and Its Related Factors in Clinical Nurses

- The Effect of The IOL Position Studied by Using Scheimpflug Camera to The Postop Astigmatism

- The Changes of Contraction Patterns in Trunk Muscles with Multidirectional Tilting Motion on the Dynamic Posturography

- Comparison of Multifidus Muscle Activity and Pelvic Tilting Angle During Typing in Nonspecific Lower Back Pain Subjects with and without Visual Biofeedback

- Spontaneous Tilting after Placement of the Gunther-Tulip Inferior Vena Caval Filter: A Case Report