Lab Med Online.

2023 Oct;13(4):290-300. 10.47429/lmo.2023.13.4.290.

Clinical Utility and Reporting of Absence of Heterozygosity in Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2552755

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.47429/lmo.2023.13.4.290

Abstract

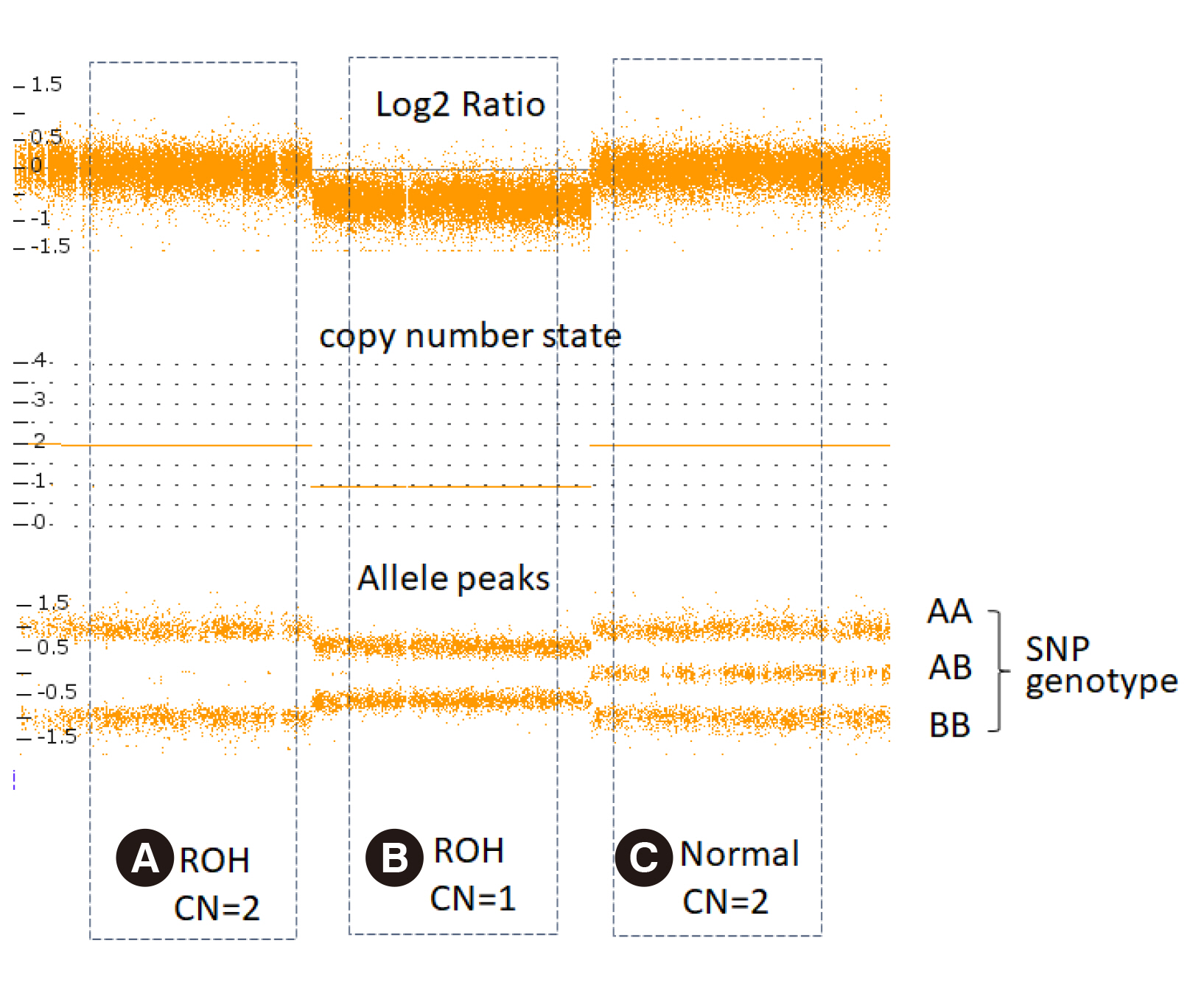

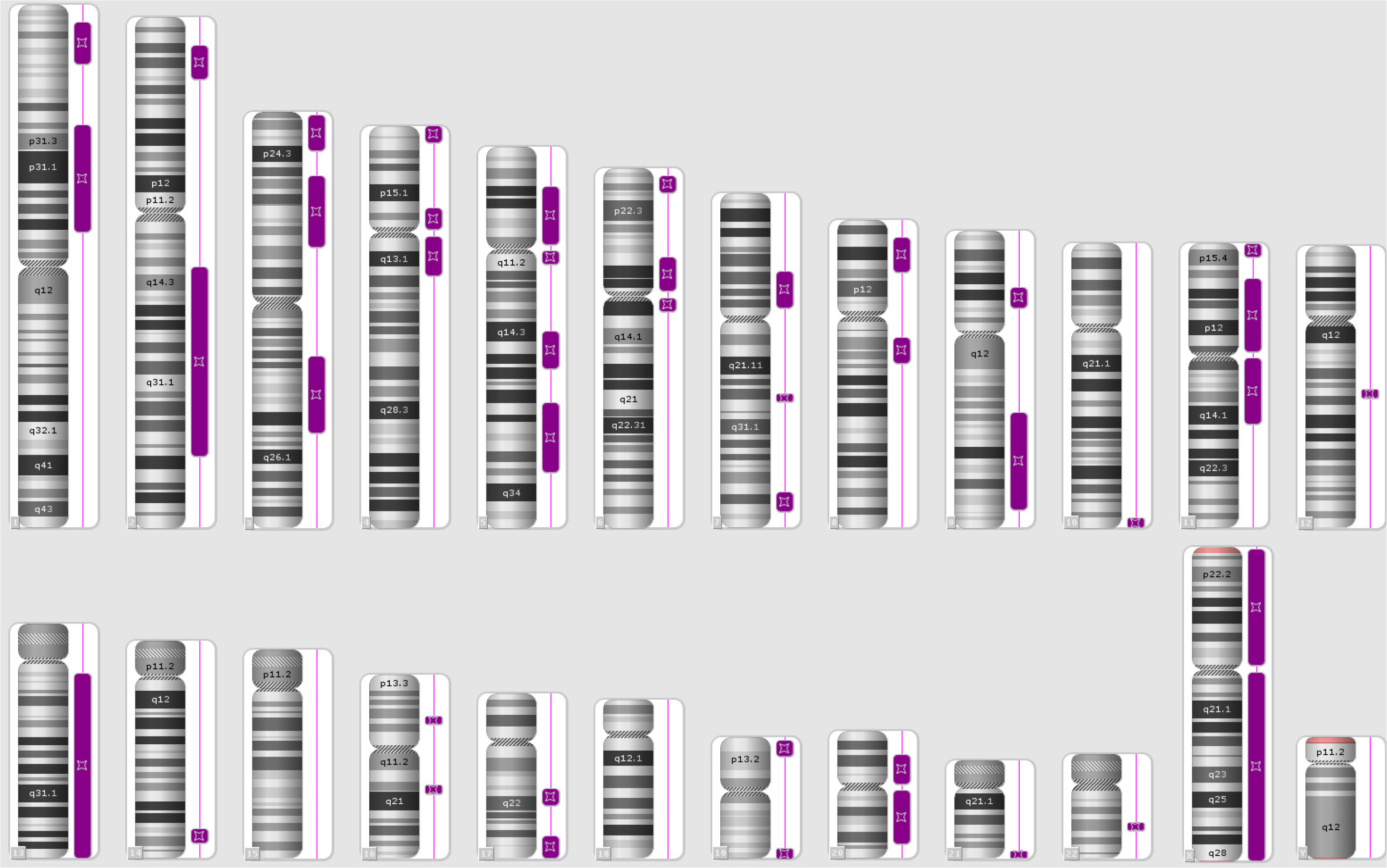

- With the widespread use of chromosomal microarray (CMA) testing in Korea, the chances for laboratories to detect the absence of heterozygosity (AOH) are increasing. AOH detected by CMA can be caused by chromosomal deletion, identity by descent (IBD) and uniparental disomy (UPD), and provides diagnostic clues for recessive and imprinted diseases, as well as information on parental blood relationship, such as consanguinity. Each laboratory should understand the clinical significance of AOH and apply it to the patient diagnosis. In addition, each laboratory should prepare laboratory policies for AOH detection and reporting results, including information of consanguinity, understanding the legal and ethical aspects.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, Biesecker LG, Brothman AR, Carter NP, et al. 2010; Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 86:749–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006. PMID: 20466091. PMCID: PMC2869000.2. Kearney HM, Kearney JB, Conlin LK. 2011; Diagnostic implications of excessive homozygosity detected by SNP-based microarrays: consanguinity, uniparental disomy, and recessive single-gene mutations. Clin Lab Med. 31:595–613. DOI: 10.1016/j.cll.2011.08.003. PMID: 22118739.3. Hillman SC, McMullan DJ, Hall G, Togneri FS, James N, Maher EJ, et al. 2013; Use of prenatal chromosomal microarray: prospective cohort study and systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 41:610–20. DOI: 10.1002/uog.12464. PMID: 23512800.4. Kirin M, McQuillan R, Franklin CS, Campbell H, McKeigue PM, Wilson JF. 2010; Genomic runs of homozygosity record population history and consanguinity. PLoS One. 5:e13996. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013996. PMID: 21085596. PMCID: PMC2981575.5. Rehder CW, David KL, Hirsch B, Toriello HV, Wilson CM, Kearney HM. 2013; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics: standards and guidelines for documenting suspected consanguinity as an incidental finding of genomic testing. Genet Med. 15:150–2. DOI: 10.1038/gim.2012.169. PMID: 23328890.6. Papenhausen P, Schwartz S, Risheg H, Keitges E, Gadi I, Burnside RD, et al. 2011; UPD detection using homozygosity profiling with a SNP genotyping microarray. Am J Med Genet A. 155:757–68. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33939. PMID: 21594998.7. Engel E. 1980; A new genetic concept: uniparental disomy and its potential effect, isodisomy. Am J Med Genet. 6:137–43. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.1320060207. PMID: 7192492.8. Spence JE, Perciaccante RG, Greig GM, Willard HF, Ledbetter DH, Hejtmancik JF, et al. 1988; Uniparental disomy as a mechanism for human genetic disease. Am J Hum Genet. 42:217–26.9. Benn P. 2021; Uniparental disomy: origin, frequency, and clinical significance. Prenat Diagn. 41:564–72. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5837. PMID: 33179335.10. Hoppman N, Rumilla K, Lauer E, Kearney H, Thorland E. 2018; Patterns of homozygosity in patients with uniparental disomy: detection rate and suggested reporting thresholds for SNP microarrays. Genet Med. 20:1522–7. DOI: 10.1038/gim.2018.24. PMID: 29565418.11. Takahashi KK, Innan H. 2022; Frequent somatic gene conversion as a mechanism for loss of heterozygosity in tumor suppressor genes. Genome Res. 32:1017–25. DOI: 10.1101/gr.276617.122. PMID: 35618418. PMCID: PMC9248884.12. Papenhausen PR, Kelly CA, Harris S, Caldwell S, Schwartz S, Penton A. 2021; Clinical significance and mechanisms associated with segmental UPD. Mol Cytogenet. 14:38. DOI: 10.1186/s13039-021-00555-0. PMID: 34284807. PMCID: PMC8290618.13. Ledbetter DH, Engel E. 1995; Uniparental disomy in humans: development of an imprinting map and its implications for prenatal diagnosis. Hum Mol Genet. 4(S1):1757–64. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1757. PMID: 8541876.14. Matsubara K, Yanagida K, Nagai T, Kagami M, Fukami M. 2020; De Novo small supernumerary marker chromosomes arising from partial trisomy rescue. Front Genet. 11:132. DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00132. PMID: 32174976. PMCID: PMC7056893.15. Del Gaudio D, Shinawi M, Astbury C, Tayeh MK, Deak KL, Raca G. 2020; Diagnostic testing for uniparental disomy: a points to consider statement from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 22:1133–41. DOI: 10.1038/s41436-020-0782-9. PMID: 32296163.16. Robinson WP. 2000; Mechanisms leading to uniparental disomy and their clinical consequences. Bioessays. 22:452–9. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200005)22:5<452::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-K.17. Nakka P, Pattillo Smith S, O'Donnell-Luria AH, McManus KF, Mountain JL, Ramachandran S, et al. 2019; Characterization of prevalence and health consequences of uniparental disomy in four million individuals from the general population. Am J Hum Genet. 105:921–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.09.016. PMID: 31607426. PMCID: PMC6848996.18. Sasaki K, Mishima H, Miura K, Yoshiura K. 2013; Uniparental disomy analysis in trios using genome-wide SNP array and whole-genome sequencing data imply segmental uniparental isodisomy in general populations. Gene. 512:267–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.035. PMID: 23111162.19. Campbell H, Carothers AD, Rudan I, Hayward C, Biloglav Z, Barac L, et al. 2007; Effects of genome-wide heterozygosity on a range of biomedically relevant human quantitative traits. Hum Mol Genet. 16:233–41. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddl473. PMID: 17220173.20. Yamazawa K, Ogata T, Ferguson-Smith AC. 2010; Uniparental disomy and human disease: an overview. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 154C:329–34. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30270. PMID: 20803655.21. Ku CS, Naidoo N, Teo SM, Pawitan Y. 2011; Regions of homozygosity and their impact on complex diseases and traits. Hum Genet. 129:1–15. DOI: 10.1007/s00439-010-0920-6. PMID: 21104274.22. Lapunzina P, Monk D. 2011; The consequences of uniparental disomy and copy number neutral loss-of-heterozygosity during human development and cancer. Biol Cell. 103:303–17. DOI: 10.1042/BC20110013. PMID: 21651501.23. Wang JC, Ross L, Mahon LW, Owen R, Hemmat M, Wang BT, et al. 2015; Regions of homozygosity identified by oligonucleotide SNP arrays: evaluating the incidence and clinical utility. Eur J Hum Genet. 23:663–71. DOI: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.153. PMID: 25118026. PMCID: PMC4402629.24. Wang Y, Li Y, Chen Y, Zhou R, Sang Z, Meng L, et al. 2020; Systematic analysis of copy-number variations associated with early pregnancy loss. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 55:96–104. DOI: 10.1002/uog.20412. PMID: 31364215.25. Schaaf CP, Scott DA, Wiszniewska J, Beaudet AL. 2011; Identification of incestuous parental relationships by SNP-based DNA microarrays. Lancet. 377:555–6. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60201-8. PMID: 21315943.26. Niida Y, Ozaki M, Shimizu M, Ueno K, Tanaka T. 2018; Classification of uniparental isodisomy patterns that cause autosomal recessive disorders: proposed mechanisms of different proportions and parental origin in each pattern. Cytogenet Genome Res. 154:137–46. DOI: 10.1159/000488572. PMID: 29656286.27. Muthusamy K, Macke EL, Klee EW, Tebben PJ, Hand JL, Hasadsri L, et al. 2020; Congenital ichthyosis in Prader-Willi syndrome associated with maternal chromosome 15 uniparental disomy: case report and review of autosomal recessive conditions unmasked by UPD. Am J Med Genet A. 182:2442–9. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61792. PMID: 32815268.28. King JE, Dexter A, Gadi I, Zvereff V, Martin M, Bloom M, et al. 2014; Maternal uniparental isodisomy causing autosomal recessive GM1 gangliosidosis: a clinical report. J Genet Couns. 23:734–41. DOI: 10.1007/s10897-014-9720-9. PMID: 24777551.29. Ferrier RA, Lowry RB, Lemire EG, Stoeber GP, Howard J, Parboosingh JS. 2009; Father-to-son transmission of an X-linked gene: a case of paternal sex chromosome heterodisomy. Am J Med Genet A. 149A:2871–3. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32994. PMID: 19921643.30. Matsubara K, Kagami M, Fukami M. 2018; Uniparental disomy as a cause of pediatric endocrine disorders. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 27:113–21. DOI: 10.1297/cpe.27.113. PMID: 30083028. PMCID: PMC6073059.31. Temple IK, James RS, Crolla JA, Sitch FL, Jacobs PA, Howell WM, et al. 1995; An imprinted gene(s) for diabetes? Nat Genet. 9:110–2. DOI: 10.1038/ng0295-110. PMID: 7719335.32. Kamiya M, Judson H, Okazaki Y, Kusakabe M, Muramatsu M, Takada S, et al. 2000; The cell cycle control gene ZAC/PLAGL1 is imprinted--a strong candidate gene for transient neonatal diabetes. Hum Mol Genet. 9:453–60. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/9.3.453. PMID: 10655556.33. Price SM, Stanhope R, Garrett C, Preece MA, Trembath RC. 1999; The spectrum of Silver-Russell syndrome: a clinical and molecular genetic study and new diagnostic criteria. J Med Genet. 36:837–42.34. Su J, Wang J, Fan X, Fu C, Zhang S, Zhang Y, et al. 2017; Mosaic UPD(7q)mat in a patient with silver Russell syndrome. Mol Cytogenet. 10:36. DOI: 10.1186/s13039-017-0337-1. PMID: 29075327. PMCID: PMC5645907.35. Choufani S, Shuman C, Weksberg R. 2010; Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 154C:343–54. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30267. PMID: 20803657.36. Slatter RE, Elliott M, Welham K, Carrera M, Schofield PN, Barton DE, et al. 1994; Mosaic uniparental disomy in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet. 31:749–53. DOI: 10.1136/jmg.31.10.749. PMID: 7837249. PMCID: PMC1050119.37. Luk HM, Ivan Lo FM, Sano S, Matsubara K, Nakamura A, Ogata T, et al. 2016; Silver-Russell syndrome in a patient with somatic mosaicism for upd(11)mat identified by buccal cell analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 170:1938–41. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37679. PMID: 27150791. PMCID: PMC5084779.38. Bullman H, Lever M, Robinson DO, Mackay DJ, Holder SE, Wakeling EL. 2008; Mosaic maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 11 in a patient with Silver-Russell syndrome. J Med Genet. 45:396–9. DOI: 10.1136/jmg.2007.057059. PMID: 18474587.39. Ioannides Y, Lokulo-Sodipe K, Mackay DJ, Davies JH, Temple IK. 2014; Temple syndrome: improving the recognition of an underdiagnosed chromosome 14 imprinting disorder: an analysis of 51 published cases. J Med Genet. 51:495–501. DOI: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102396. PMID: 24891339.40. Sanlaville D, Aubry MC, Dumez Y, Nolen MC, Amiel J, Pinson MP, et al. 2000; Maternal uniparental heterodisomy of chromosome 14: chromosomal mechanism and clinical follow up. J Med Genet. 37:525–8. DOI: 10.1136/jmg.37.7.525. PMID: 10882756. PMCID: PMC1734622.41. Kagami M, Kurosawa K, Miyazaki O, Ishino F, Matsuoka K, Ogata T. 2015; Comprehensive clinical studies in 34 patients with molecularly defined UPD(14)pat and related conditions (Kagami-Ogata syndrome). Eur J Hum Genet. 23:1488–98. DOI: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.13. PMID: 25689926. PMCID: PMC4613461.42. Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ. 2012; Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med. 14:10–26. DOI: 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0. PMID: 22237428.43. Fridman C, Koiffmann CP. 2000; Origin of uniparental disomy 15 in patients with Prader-Willi or Angelman syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 94:249–53. DOI: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000918)94:3<249::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID: 10995513.44. Buiting K. 2010; Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 154C:365–76. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30273. PMID: 20803659.45. Poyatos D, Guitart M, Gabau E, Brun C, Mila M, Vaquerizo J, et al. 2002; Severe phenotype in Angelman syndrome resulting from paternal isochromosome 15. J Med Genet. 39:E4. DOI: 10.1136/jmg.39.2.e4. PMID: 11836373. PMCID: PMC1735026.46. Dixit A, Chandler KE, Lever M, Poole RL, Bullman H, Mughal MZ, et al. 2013; Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b due to paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 20q. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98:E103–8. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2012-2639. PMID: 23144470.47. Mulchandani S, Bhoj EJ, Luo M, Powell-Hamilton N, Jenny K, Gripp KW, et al. 2016; Maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 20: a novel imprinting disorder of growth failure. Genet Med. 18:309–15. DOI: 10.1038/gim.2015.103. PMID: 26248010.48. Kawashima S, Nakamura A, Inoue T, Matsubara K, Horikawa R, Wakui K, et al. 2018; Maternal uniparental disomy for chromosome 20: physical and endocrinological characteristics of five patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 103:2083–8. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2017-02780. PMID: 29878129.49. Yip MY. 2014; Uniparental disomy in Robertsonian translocations: strategies for uniparental disomy testing. Transl Pediatr. 3:98–107.50. Berend SA, Horwitz J, McCaskill C, Shaffer LG. 2000; Identification of uniparental disomy following prenatal detection of Robertsonian translocations and isochromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 66:1787–93. DOI: 10.1086/302916. PMID: 10775524. PMCID: PMC1378034.51. Silverstein S, Lerer I, Sagi M, Frumkin A, Ben-Neriah Z, Abeliovich D. 2002; Uniparental disomy in fetuses diagnosed with balanced Robertsonian translocations: risk estimate. Prenat Diagn. 22:649–51. DOI: 10.1002/pd.370. PMID: 12210570.52. Liehr T, Klein E, Mrasek K, Kosyakova N, Guilherme RS, Aust N, et al. 2013; Clinical impact of somatic mosaicism in cases with small supernumerary marker chromosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 139:158–63. DOI: 10.1159/000346026. PMID: 23295254.53. Behnecke A, Hinderhofer K, Jauch A, Janssen JW, Moog U. 2012; Silver-Russell syndrome due to maternal uniparental disomy 7 and a familial reciprocal translocation t(7;13). Clin Genet. 82:494–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01792.x. PMID: 21954990.54. Eggermann T, Soellner L, Buiting K, Kotzot D. 2015; Mosaicism and uniparental disomy in prenatal diagnosis. Trends Mol Med. 21:77–87. DOI: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.010. PMID: 25547535.55. Benn P, Malvestiti F, Grimi B, Maggi F, Simoni G, Grati FR. 2019; Rare autosomal trisomies: comparison of detection through cell-free DNA analysis and direct chromosome preparation of chorionic villus samples. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 54:458–67. DOI: 10.1002/uog.20383. PMID: 31237735.56. Christian SL, Smith AC, Macha M, Black SH, Elder FF, Johnson JM, et al. 1996; Prenatal diagnosis of uniparental disomy 15 following trisomy 15 mosaicism. Prenat Diagn. 16:323–32. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199604)16:4<323::AID-PD856>3.0.CO;2-5.57. Trisomy 15 CPM: probable origins, pregnancy outcome and risk of fetal UPD: European Collaborative Research on Mosaicism in CVS (EUCROMIC). 1999; Prenat Diagn. 19:29–35. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199901)19:1<29::AID-PD462>3.0.CO;2-B.58. Robinson WP, Langlois S, Schuffenhauer S, Horsthemke B, Michaelis RC, Christian S, et al. 1996; Cytogenetic and age-dependent risk factors associated with uniparental disomy 15. Prenat Diagn. 16:837–44. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199609)16:9<837::AID-PD956>3.0.CO;2-7.59. Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. 2002; Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e57. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. PMID: 12060695. PMCID: PMC117299.60. Magi A, Tattini L, Palombo F, Benelli M, Gialluisi A, Giusti B, et al. 2014; H3M2: detection of runs of homozygosity from whole-exome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 30:2852–9. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu401. PMID: 24966365.61. King DA, Fitzgerald TW, Miller R, Canham N, Clayton-Smith J, Johnson D, et al. 2014; A novel method for detecting uniparental disomy from trio genotypes identifies a significant excess in children with developmental disorders. Genome Res. 24:673–87. DOI: 10.1101/gr.160465.113. PMID: 24356988. PMCID: PMC3975066.62. Shaffer LG, Agan N, Goldberg JD, Ledbetter DH, Longshore JW, Cassidy SB. 2001; American College of Medical Genetics statement of diagnostic testing for uniparental disomy. Genet Med. 3:206–11. DOI: 10.1097/00125817-200105000-00011. PMID: 11388763. PMCID: PMC3111049.63. Oniya O, Neves K, Ahmed B, Konje JC. 2019; A review of the reproductive consequences of consanguinity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 232:87–96. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.042. PMID: 30502592.64. Carothers AD, Rudan I, Kolcic I, Polasek O, Hayward C, Wright AF, et al. 2006; Estimating human inbreeding coefficients: comparison of genealogical and marker heterozygosity approaches. Ann Hum Genet. 70:666–76. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00263.x. PMID: 16907711.65. Sund KL, Zimmerman SL, Thomas C, Mitchell AL, Prada CE, Grote L, et al. 2013; Regions of homozygosity identified by SNP microarray analysis aid in the diagnosis of autosomal recessive disease and incidentally detect parental blood relationships. Genet Med. 15:70–8. DOI: 10.1038/gim.2012.94. PMID: 22858719.66. Gonzales PR, Andersen EF, Brown TR, Horner VL, Horwitz J, Rehder CW, et al. 2022; Interpretation and reporting of large regions of homozygosity and suspected consanguinity/uniparental disomy, 2021 revision: a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 24:255–61. DOI: 10.1016/j.gim.2021.10.004. PMID: 34906464.67. Pemberton TJ, Absher D, Feldman MW, Myers RM, Rosenberg NA, Li JZ. 2012; Genomic patterns of homozygosity in worldwide human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 91:275–92. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.014. PMID: 22883143. PMCID: PMC3415543.68. Wang JC, Radcliff J, Coe SJ, Mahon LW. 2019; Effects of platforms, size filter cutoffs, and targeted regions of cytogenomic microarray on detection of copy number variants and uniparental disomy in prenatal diagnosis: results from 5026 pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 39:137–56. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5375. PMID: 30734327.69. Delgado F, Tabor HK, Chow PM, Conta JH, Feldman KW, Tsuchiya KD, et al. 2015; Single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays and unexpected consanguinity: considerations for clinicians when returning results to families. Genet Med. 17:400–4. DOI: 10.1038/gim.2014.119. PMID: 25232848. PMCID: PMC4404161.70. Grote L, Myers M, Lovell A, Saal H, Lipscomb Sund K. 2012; Variability in laboratory reporting practices for regions of homozygosity indicating parental relatedness as identified by SNP microarray testing. Genet Med. 14:971–6. DOI: 10.1038/gim.2012.83. PMID: 22791212.71. Grote L, Myers M, Lovell A, Saal H, Sund KL. 2014; Variable approaches to genetic counseling for microarray regions of homozygosity associated with parental relatedness. Am J Med Genet A. 164A:87–98. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36206. PMID: 24243712.72. Burgess AW. 2007; How many red flags does it take? Am J Nurs. 107:28–31. DOI: 10.1097/00000446-200701000-00017. PMID: 17200630.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Practical Guidelines for Chromosomal Microarray Analysis for Constitutional Abnormalities: Part II, Reporting and Interpretation

- Clinical application of prenatal chromosomal microarray

- Prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis of fetus with increased nuchal translucency

- Usefulness of Chromosomal Microarray in Hematologic Malignancies: A Case of Aggressive NK-cell Leukemia with 1q Abnormality

- Triploidy that escaped diagnosis using chromosomal microarray testing in early pregnancy loss: Two cases and a literature review