Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2023 Dec;29(4):302-316. 10.4069/kjwhn.2023.11.13.1.

An explanatory model of quality of life in high-risk pregnant women in Korea: a structural equation model

- Affiliations

-

- 1College of Nursing, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea

- KMID: 2550994

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2023.11.13.1

Abstract

- Purpose

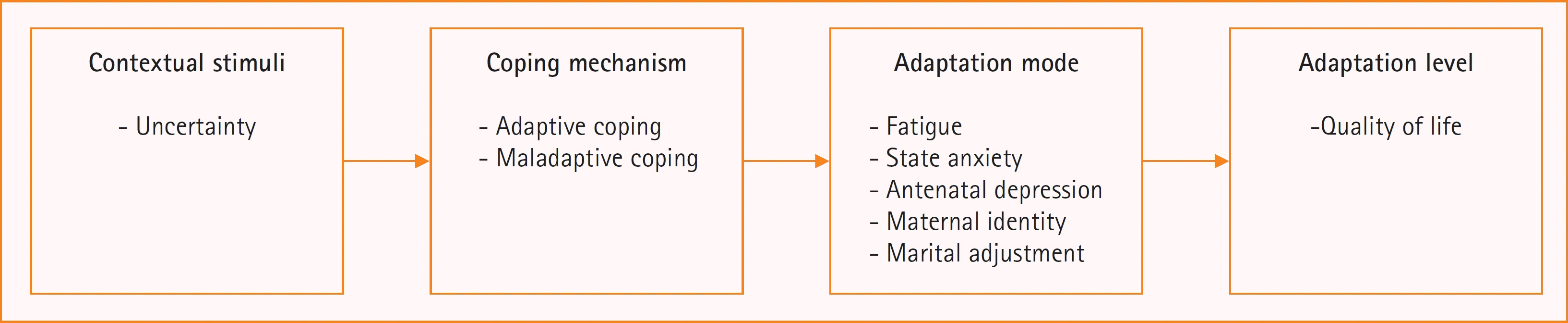

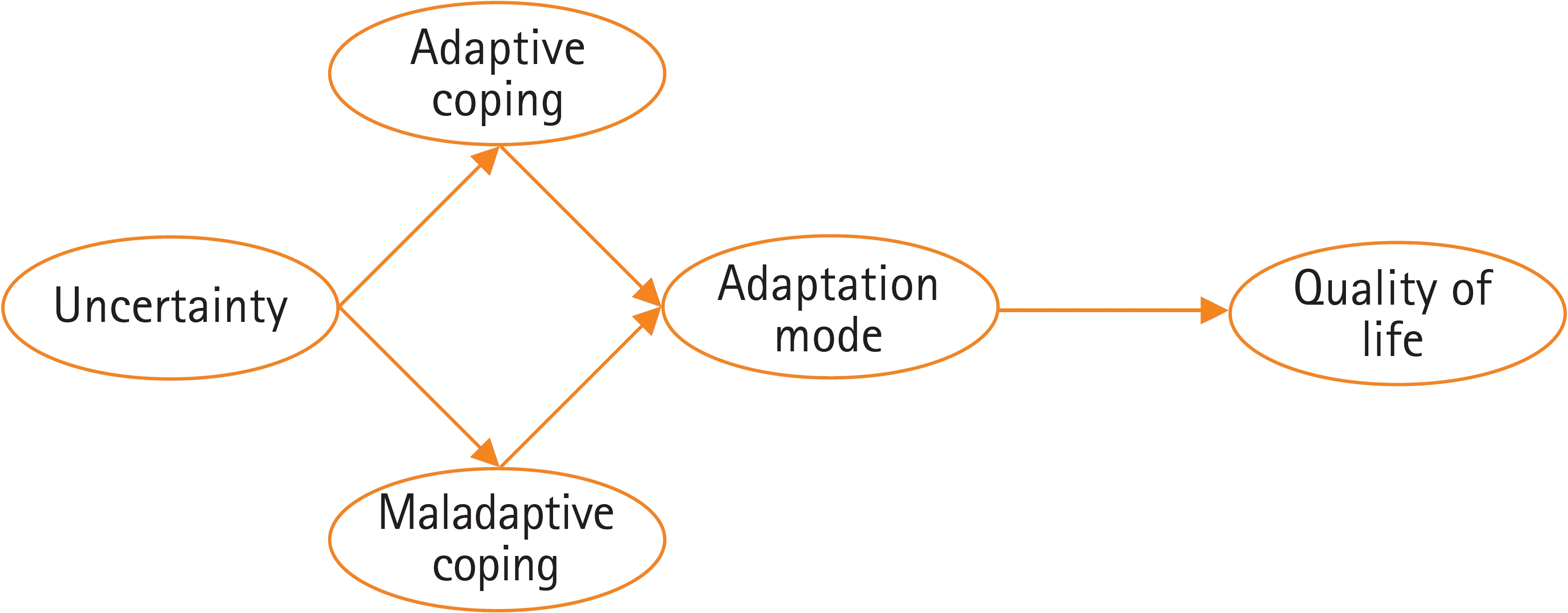

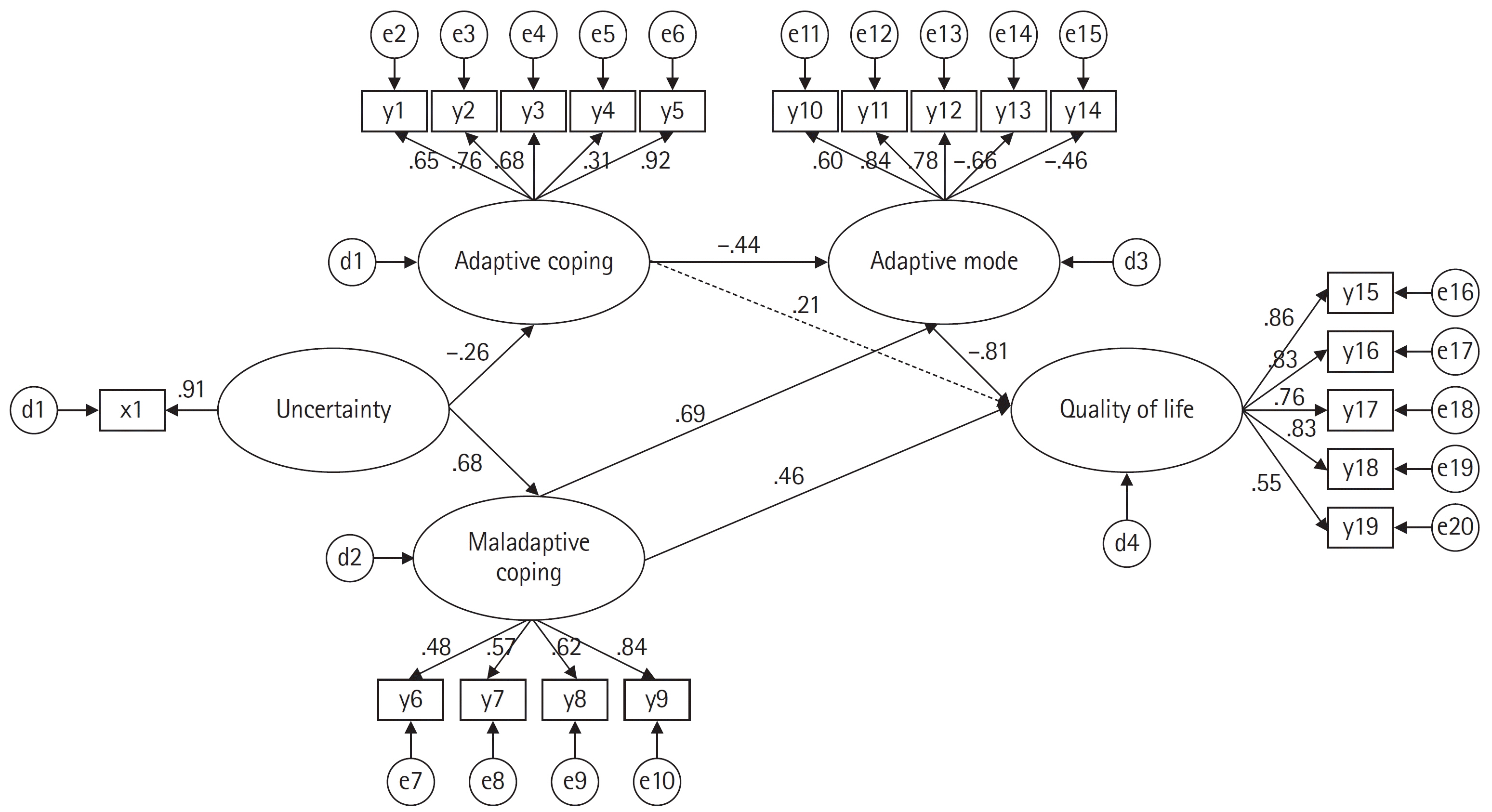

This study aimed to develop and validate a structural model for the quality of life (QoL) among high-risk pregnant women, based on Roy’s adaptation model. Methods: This cross-sectional study collected data from 333 first-time mothers diagnosed with a high-risk pregnancy in two obstetrics and gynecology clinics in Cheonan, Korea, or participating in an online community, between October 20, 2021 and February 20, 2022. Structured questionnaires measured QoL, contextual stimuli (uncertainty), coping (adaptive or maladaptive), and adaptation mode (fatigue, state anxiety, antenatal depression, maternal identity, and marital adjustment). Results: The mean age of the respondents was 35.29±3.72 years, ranging from 26 to 45 years. The most common high-risk pregnancy diagnosis was gestational diabetes (26.1%). followed by preterm labor (21.6%). QoL was higher than average (18.63±3.80). Above-moderate mean scores were obtained for all domains (psychological/baby, 19.03; socioeconomic, 19.00; relational/spouse-partner, 20.99; relational/family-friends, 19.18; and health and functioning, 16.18). The final model explained 51% of variance in QoL in high-risk pregnant women, with acceptable overall model fit. Adaptation mode (β=–.81, p=.034) and maladaptive coping (β=.46 p=.043) directly affected QoL, and uncertainty (β=–. 21, p=.004), adaptive coping (β=.36 p=.026), and maladaptive coping (β=–.56 p=.023) indirectly affected QoL. Conclusion: It is essential to develop nursing interventions aimed at enhancing appropriate coping strategies to improve QoL in high-risk pregnant women. By reinforcing adaptive coping strategies and mitigating maladaptive coping, these interventions can contribute to better maternal and fetal outcomes and improve the overall well-being of high-risk pregnant women.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Korean Statistical Information Service. 2021 Birth statistics [Internet]. Daejeon, Korea: Statistics Korea;2022. [cited 2023 Apr 16]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=204&tag=&act=view&list_no=419974&ref_bid=203,204,205,206,207,210,211.2. Lancaster EE, Lapato DM, Jackson-Cook C, Strauss JF 3rd, Roberson-Nay R, York TP. Maternal biological age assessed in early pregnancy is associated with gestational age at birth. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):15440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94281-7.

Article3. Korean Statistical Information Service. 2020 Birth: population trend survey tables for Korea [Internet]. Daejeon, Korea: Statistics Korea; 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 16]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/search/search.do?query=%EA%B3%A0%ED%98%88%EC%95%95.4. Hwang JY. Reclassification of high-risk pregnancy for maternal-fetal healthcare providers. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2020; 24(2):65–74. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2020.24.2.65.

Article5. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Preterm labor [Internet]. Wonju, Korea: Author;2021. [cited 2023 Apr 16]. Available from: http://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olapMfrnIntrsIlnsInfo.do.6. Kao MH, Hsu PF, Tien SF, Chen CP. Effects of support interventions in women hospitalized with preterm labor. Clin Nurs Res. 2019; 28(6):726–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773817744323.

Article7. Kim EM, Hong S. Impact of uncertainty on the anxiety of hospitalized pregnant women diagnosed with preterm labor: focusing on mediating effect of uncertainty appraisal and coping style. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2018; 48(4):485–496. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2018.48.4.485.

Article8. Schmuke AD. Factors affecting uncertainty in women with high-risk pregnancies. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2019; 44(6):317–324. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000563.

Article9. Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Pers Individ Dif. 2001; 30(8):1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6.

Article10. Naseiri S, Askarizadeh G, Masoud Fazilat FP. The role of cognitive regulation strategies of emotion, psychological hardiness and optimism in the prediction of death anxiety of women in their third trimester of pregnancy. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2017; 4(6):50–58. https://doi.org/10.21859/ijpn-04068.

Article11. Jirapaet V. Effects of an empowerment program on coping, quality of life, and the maternal role adaptation of Thai HIV-infected mothers. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2000; 11(4):34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60394-4.

Article12. Gadelha IP, Aquino PS, Balsells MM, Diniz FF, Pinheiro AK, Ribeiro SG, et al. Quality of life of high risk pregnant women during prenatal care. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020; 73 Suppl 5:e20190595. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0595.

Article13. Marchetti D, Carrozzino D, Fraticelli F, Fulcheri M, Vitacolonna E. Quality of life in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Diabetes Res. 2017; 2017:7058082. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7058082.

Article14. Kang H, Nho JH, Kang H, Lee S, Lee H, Choi S. Influence of fatigue, depression and anxiety on quality of life in pregnant women with preterm labor. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2016; 22(4):254–263. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2016.22.4.254.

Article15. Morin M, Claris O, Dussart C, Frelat A, de Place A, Molinier L, et al. Health-related quality of life during pregnancy: a repeated measures study of changes from the first trimester to birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019; 98(10):1282–1291. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13624.

Article16. Kim KT, Cho YW, Bae JG. Quality of sleep and quality of life measured monthly in pregnant women in South Korea. Sleep Breath. 2020; 24(3):1219–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-020-02041-0.

Article17. Roy C, Andrews HA. The Roy adaptation model. 2nd ed. Stamford (CT): Appleton & Lange;1999. p. 574.18. Amanak K, Sevil U, Karacam Z. The impact of prenatal education based on the Roy adaptation model on gestational hypertension, adaptation to pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019; 69(1):11–17.19. Widiasih R, Trisyani M, Maryati I, Hermayanti Y. Nursing care of premature rupture of membranes in pregnancy: Roy adaptation model. J Matern Care Reprod Health. 2018; 1(1):87–99. https://doi.org/10.36780/jmcrh.v1i1.18.

Article20. Fawcett J, Tulman L. Adaptation to high-risk childbearing: a preliminary situation-specific theory. Aquichan. 2018; 18(4):407–414. https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2018.18.4.3.

Article21. Dobratz MC. Moving nursing science forward within the framework of the Roy adaptation model. Nurs Sci Q. 2008; 21(3):255–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318408319289.

Article22. Mirzakhani K, Ebadi A, Faridhosseini F, Khadivzadeh T. Well-being in high-risk pregnancy: an integrative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):526. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03190-6.

Article23. Abrar A, Fairbrother N, Smith AP, Skoll A, Albert AYK. Anxiety among women experiencing medically complicated pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Birth. 2020; 47(1):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12443.

Article24. Lindegren ML, Kennedy CE, Bain-Brickley D, Azman H, Creanga AA, Butler LM, et al. Integration of HIV/AIDS services with maternal, neonatal and child health, nutrition, and family planning services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; (9):CD010119. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010119.

Article25. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Support for medical expenses for high-risk pregnant women [Internet]. Sejong, Korea: Author;2022. [cited 2023 Apr 16]. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=032901&CONT_SEQ=369619.26. Shin GG. Amos 23 statistical analysis follow-up. 2nd ed. Seoul: Chungram Books;2016. p. 491.27. Dadi AF, Miller ER, Woodman R, Bisetegn TA, Mwanri L. Antenatal depression and its potential causal mechanisms among pregnant mothers in Gondar town: application of structural equation model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02859-2.

Article28. Hill PD, Aldag JC. Maternal perceived quality of life following childbirth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007; 36(4):328–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00164.x.

Article29. Choi SY, Gu HJ, Ryu EJ. Effects of fatigue and postpartum depression on maternal perceived quality of life (MAPP-QOL) in early postpartum mothers. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2011; 17(2):118–125. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2011.17.2.118.

Article30. Mishel MH, Clayton MF. Theories of uncertainty in illness. In : Smith MJ, Liehr PR, editors. Middle range theory of nursing. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company;2008. p. 55–84.31. Chung C, Kim MJ, Rhee MH, Do HG. Functional status and psychosocial adjustment in gynecologic cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2005; 11(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2005.11.1.58.

Article32. Kim SH. A study on relationships among the stressful events, cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychological well-being [master’s thesis]. Seoul: The Catholic University of Korea;2004. 61.33. Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij VV, Van Den Kommer T, Teerds J. Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a comparison between adolescents and adults. J Adolesc. 2002; 25(6):603–611. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2002.0507.

Article34. Milligan R, Lenz ER, Parks PL, Pugh LC, Kitzman H. Postpartum fatigue: clarifying a concept. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1996; 10(3):279–291.35. Song JE. A structural model of postpartum fatigue of the primipara in Korea [dissertation]. Seoul: Yonsei University;2007. 134.36. Spielberger CD, Gonzalez-Reigosa F, Martinez-Urrutia A, Natalicio LF, Natalicio DS. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Interam J Psychol. 1971; 5(3 & 4):145–158.37. Kim J, Shin D. A study based on the standardization of the STAI for Korea. New Med J. 1978; 21(11):69–75.38. Kim YK, Hur JW, Kim KH, Oh KS, Shin YC. Clinical application of Korean version of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2008; 47(1):36–44.39. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Article40. Kim HW, Hong KJ. Development of a maternal identity scale for pregnant women. J Korean Acad Nurs. 1996; 26(3):531–543. https://doi.org/10.4040/jnas.1996.26.3.531.

Article41. Cho H, Choi SM, Oh HJ, Kwon JH. Validity of the short forms of the Korean Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2011; 23(3):655–670.42. Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976; 38(1):15–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/350547.

Article43. Pahlevan Sharif S, Ahadzadeh AS, Perdamen HK. Uncertainty and quality of life of Malaysian women with breast cancer: mediating role of coping styles and mood states. Appl Nurs Res. 2017; 38:88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2017.09.012.

Article44. Kang DI, Park E. Do taegyo practices, self-esteem, and social support affect maternal-fetal attachment in high-risk pregnant women? A cross-sectional survey. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2022; 28(4):338–347. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2022.12.16.

Article45. Yoo SM. Pregnancy stress and maternal-fetal attachment among high-risk pregnant women with different coping strategies [master’s thesis]. Busan: Pusan National University;2021. 61.46. Kim JS. Effects of pregnant woman social support, pregnancy stress and anxiety on quality of life. J Converg Inf Technol. 2021; 11(5):50–56. https://doi.org/10.22156/CS4SMB.2021.11.05.050.

Article47. Jeong YJ, Nho JH, Kim HY, Kim JY. Factors influencing quality of life in early postpartum women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(6):2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062988.

Article48. Lagadec N, Steinecker M, Kapassi A, Magnier AM, Chastang J, Robert S, et al. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1):455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4.

Article49. Park HJ. Factors affecting quality of life in pregnant women [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Korea University;2021. 89.50. Kim HJ, Chun N. Effects of a supportive program on uncertainty, anxiety, and maternal-fetal attachment in women with high-risk pregnancy. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2020; 26(2):180–190. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2020.06.17.

Article51. Williamson SP, Moffitt RL, Broadbent J, Neumann DL, Hamblin PS. Coping, wellbeing, and psychopathology during high-risk pregnancy: a systematic review. Midwifery. 2023; 116:103556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103556.

Article52. Chung MY, Hwang KH, Cho OH. Relationship between fatigue, sleep disturbance, and gestational stress among pregnant women in the late stages. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2014; 20(3):195–203. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2014.20.3.195.

Article53. Schubert KO, Air T, Clark SR, Grzeskowiak LE, Miller E, Dekker GA, et al. Trajectories of anxiety and health related quality of life during pregnancy. PLoS One. 2017; 12(7):e0181149. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181149.

Article54. Koh M, Kim J, Yoo H, Kim SA, Ahn S. Development and application of a couple-centered antenatal education program in Korea. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2021; 27(2):141–152. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2021.06.20.

Article55. Seo HJ, Song JE, Lee Y, Ahn JA. Effects of stress, depression, and spousal and familial support on maternal identity in pregnant women. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2020; 26(1):84–92. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2020.03.17.

Article56. Lee SM, Park HJ. Relationship among emotional clarity, maternal identity, and fetal attachment in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2017; 23(2):99–108. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2017.23.2.99.

Article57. Oh YK, Hwang SY. Impact of uncertainty on the quality of life of young breast cancer patients: focusing on mediating effect of marital intimacy. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2018; 48(1):50–58. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2018.48.1.50.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Structural Equation Model of Health-Related Quality of Life in School Age Children with Asthma

- Quality of Life in Middle-aged Men with Prostatic hyperplasia: A Structural Equation Model

- The Role of Negative Affect in the Assessment of Quality of Life among Women with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

- Health-related quality of life for older patients with chronic low back pain: A structural equation modeling study

- Model Setting and Interpretation of Results in Research Using Structural Equation Modeling: A Checklist with Guiding Questions for Reporting