Restor Dent Endod.

2023 Aug;48(3):e30. 10.5395/rde.2023.48.e30.

Comparison between a bulk-fill resinbased composite and three luting materials on the cementation of fiberglass-reinforced posts

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

- 2Centro Universitário do Estado do Pará, Belém, PA, Brazil

- 3Department of Biomaterials and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

- KMID: 2548233

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2023.48.e30

Abstract

Objectives

This study verified the possibility of cementing fiberglass-reinforced posts using a flowable bulk-fill composite (BF), comparing its push-out bond strength and microhardness with these properties of 3 luting materials.

Materials and Methods

Sixty endodontically treated bovine roots were used. Posts were cemented using conventional dual-cured cement (CC); self-adhesive cement (SA); dual-cured composite (RC); and BF. Push-out bond strength (n = 10) and microhardness (n = 5) tests were performed after 1 week and 4 months of storage. Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), 1-way ANOVA, t-test, and Tukey post-hoc tests were applied for the pushout bond strength and microhardness results; and Pearson correlation test was applied to verify the correlation between push-out bond strength and microhardness results (α = 0.05).

Results

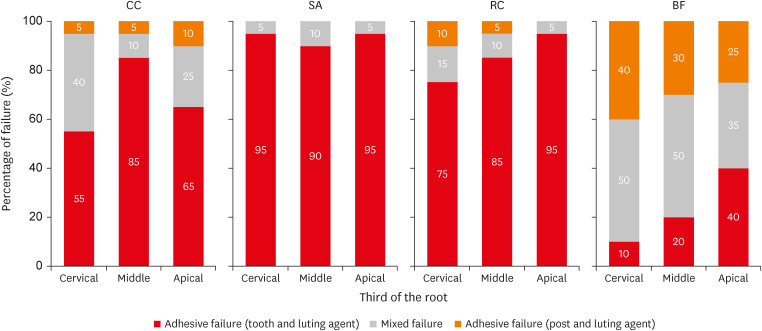

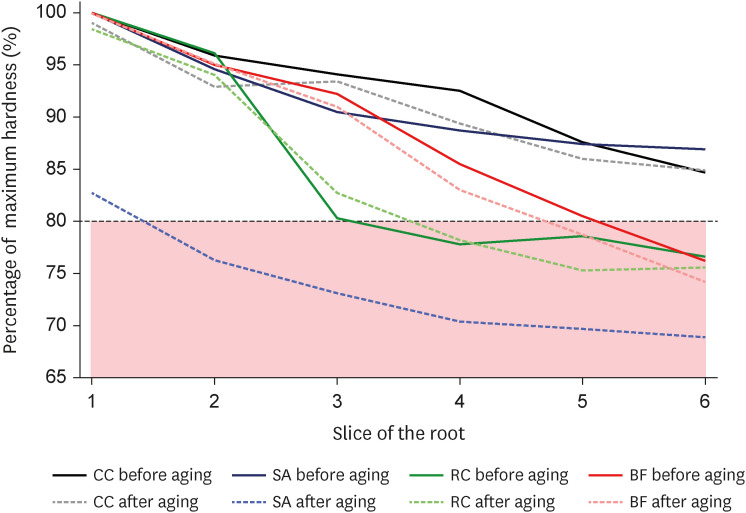

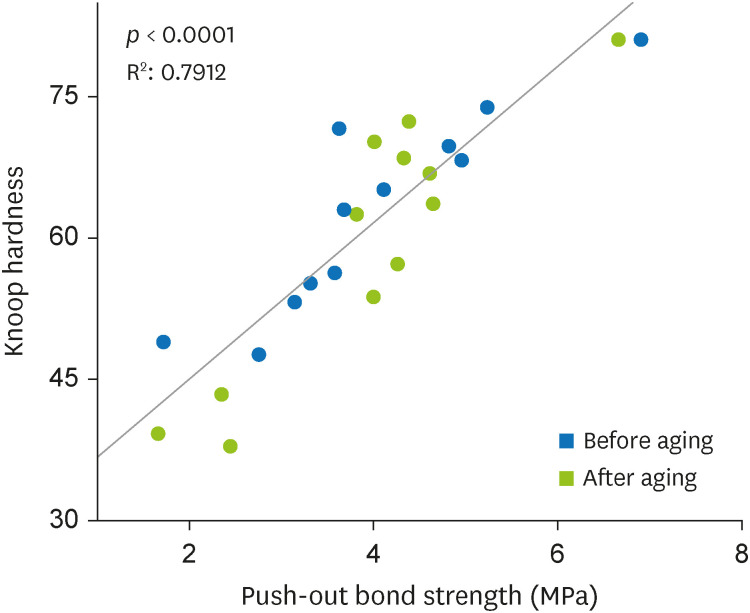

BF presented higher push-out bond strength than CC and SA in the cervical third before aging (p < 0.01). No differences were found between push-out bond strength before and after aging for all the luting materials (p = 0.84). Regarding hardness, only SA presented higher values measured before than after aging (p < 0.01). RC and BF did not present 80% of the maximum hardness at the apical regions. A strong positive correlation was found between the luting materials' push-out bond strength and microhardness (p < 0.01, R 2 = 0.7912).

Conclusions

The BF presented comparable or higher push-out bond strength and microhardness than the luting materials, which indicates that it could be used for cementing resin posts in situations where adequate light curing is possible.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Morgano SM, Rodrigues AH, Sabrosa CE. Restoration of endodontically treated teeth. Dent Clin North Am. 2004; 48:vi397–vi416.

Article2. Santos AF, Meira JB, Tanaka CB, Xavier TA, Ballester RY, Lima RG, Pfeifer CS, Versluis A. Can fiber posts increase root stresses and reduce fracture? J Dent Res. 2010; 89:587–591. PMID: 20348486.

Article3. Giachetti L, Scaminaci Russo D, Bertini F, Giuliani V. Translucent fiber post cementation using a light-curing adhesive/composite system: SEM analysis and pull-out test. J Dent. 2004; 32:629–634. PMID: 15476957.

Article4. Bitter K, Meyer-Lueckel H, Priehn K, Kanjuparambil JP, Neumann K, Kielbassa AM. Effects of luting agent and thermocycling on bond strengths to root canal dentine. Int Endod J. 2006; 39:809–818. PMID: 16948667.

Article5. Bolhuis P, de Gee A, Feilzer A. The influence of fatigue loading on the quality of the cement layer and retention strength of carbon fiber post-resin composite core restorations. Oper Dent. 2005; 30:220–227. PMID: 15853108.6. Schwartz RS. Adhesive dentistry and endodontics. Part 2: bonding in the root canal system-the promise and the problems: a review. J Endod. 2006; 32:1125–1134. PMID: 17174666.

Article7. Goracci C, Sadek FT, Fabianelli A, Tay FR, Ferrari M. Evaluation of the adhesion of fiber posts to intraradicular dentin. Oper Dent. 2005; 30:627–635. PMID: 16268398.8. Ferracane JL, Greener EH. The effect of resin formulation on the degree of conversion and mechanical properties of dental restorative resins. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986; 20:121–131. PMID: 3949822.

Article9. Nakano EL, de Souza A, Boaro L, Catalani LH, Braga RR, Gonçalves F. Polymerization stress and gap formation of self-adhesive, bulk-fill and flowable composite resins. Oper Dent. 2020; 45:E308–E316. PMID: 32516396.

Article10. Lima RBW, Troconis CCM, Moreno MBP, Murillo-Gómez F, De Goes MF. Depth of cure of bulk fill resin composites: a systematic review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2018; 30:492–501. PMID: 30375146.

Article11. Helvey GA. Creating super dentin: using flowable composites as luting agents to help prevent secondary caries. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013; 34:288–300. PMID: 23895566.12. Tomaselli LO, Oliveira DCRS, Favarão J, Silva AFD, Pires-de-Souza FCP, Geraldeli S, Sinhoreti MAC. Influence of pre-heating regular resin composites and flowable composites on luting ceramic veneers with different thicknesses. Braz Dent J. 2019; 30:459–466. PMID: 31596330.

Article13. Ghodsi S, Aghamohseni MM, Arzani S, Rasaeipour S, Shekarian M. Cement selection criteria for different types of intracanal posts. Dent Res J. 2022; 19:51.

Article14. Sarkis-Onofre R, Skupien JA, Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Pereira-Cenci T. The role of resin cement on bond strength of glass-fiber posts luted into root canals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Oper Dent. 2014; 39:E31–E44. PMID: 23937401.15. Bergoli CD, Brondani LP, Wandscher VF, Pereira G, Cenci MS, Pereira-Cenci T, Valandro LF. A multicenter randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial of fiber post cementation strategies. Oper Dent. 2018; 43:128–135. PMID: 29504877.

Article16. Moorthy A, Hogg CH, Dowling AH, Grufferty BF, Benetti AR, Fleming GJ. Cuspal deflection and microleakage in premolar teeth restored with bulk-fill flowable resin-based composite base materials. J Dent. 2012; 40:500–505. PMID: 22390980.

Article17. Braga RR, Ballester RY, Ferracane JL. Factors involved in the development of polymerization shrinkage stress in resin-composites: a systematic review. Dent Mater. 2005; 21:962–970. PMID: 16085301.

Article18. do Carmo SS, Néspoli FFP, Bachmann L, Miranda CES, Castro-Raucci LMS, Oliveira IR, Raucci-Neto W. Influence of early mineral deposits of silicate- and aluminate-based cements on push-out bond strength to root dentine. Int Endod J. 2018; 51:92–101. PMID: 28470849.

Article19. Goracci C, Grandini S, Bossù M, Bertelli E, Ferrari M. Laboratory assessment of the retentive potential of adhesive posts: a review. J Dent. 2007; 35:827–835. PMID: 17766026.

Article20. De-Deus G, Souza E, Versiani M. Methodological considerations on push-out tests in Endodontics. Int Endod J. 2015; 48:501–503. PMID: 25851123.

Article21. Palin WM, Leprince JG, Hadis MA. Shining a light on high volume photocurable materials. Dent Mater. 2018; 34:695–710. PMID: 29549967.

Article22. Watts DC, Amer O, Combe EC. Characteristics of visible-light-activated composite systems. Br Dent J. 1984; 156:209–215. PMID: 6584142.

Article23. Shortall AC, Wilson HJ, Harrington E. Depth of cure of radiation-activated composite restoratives--influence of shade and opacity. J Oral Rehabil. 1995; 22:337–342. PMID: 7616343.

Article24. Rosado L, Münchow EA, de Oliveira E, Lacerda-Santos R, Freitas DQ, Carlo HL, Verner FS. Translucency and radiopacity of dental resin composites - is there a direct relation? Oper Dent. 2023; 48:E61–E69. PMID: 37079916.

Article25. Vieira C, Bachmann L, De Andrade Lima Chaves C, Correa Silva-Sousa YT, Correa Da Silva SR, Alfredo E. Light transmission and bond strength of glass fiber posts submitted to different surface treatments. J Prosthet Dent. 2021; 125:674.e1–674.e7.

Article26. Shimokawa C, Turbino ML, Giannini M, Braga RR, Price RB. Effect of curing light and exposure time on the polymerization of bulk-fill resin-based composites in molar teeth. Oper Dent. 2020; 45:E141–E155. PMID: 32053458.

Article27. Montanari M, Prati C, Piana G. Differential hydrolytic degradation of dentin bonds when luting carbon fiber posts to the root canal. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011; 16:e411–e417. PMID: 20526268.

Article28. Ramos MB, Pegoraro TA, Pegoraro LF, Carvalho RM. Effects of curing protocol and storage time on the micro-hardness of resin cements used to lute fiber-reinforced resin posts. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012; 20:556–562. PMID: 23138743.

Article29. Tay FR, Carvalho RM, Pashley DH. Water movement across bonded dentin - too much of a good thing. J Appl Oral Sci. 2004; 12:12–25.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The effect of individualization of fiberglass posts using bulk-fill resin-based composites on cementation: an in vitro study

- Currently there are so many fiber reinforced composite posts in the market. Some products are factory silanated but some products are not. Should I use silane for surface treatment of fiber reinforced composite posts?

- Comparison of mechanical properties of a new fiber reinforced composite and bulk filling composites

- Fracture resistance of upper central incisors restored with different posts and cores

- Clinical performance of class I cavities restored with bulk fill composite at a 1-year follow-up using the FDI criteria: a randomized clinical trial