Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2023 Sep;29(3):243-252. 10.4069/kjwhn.2023.09.11.

Effects of anxiety, depression, social support, and physical health status on the health-related quality of life of pregnant women in post-pandemic Korea: a cross-sectional study

- Affiliations

-

- 1College of Nursing, Kongju National University, Kongju, Korea

- 2School of Nursing and Research Institute in Nursing Science, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea

- 3College of Nursing, Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2547160

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2023.09.11

Abstract

- Purpose

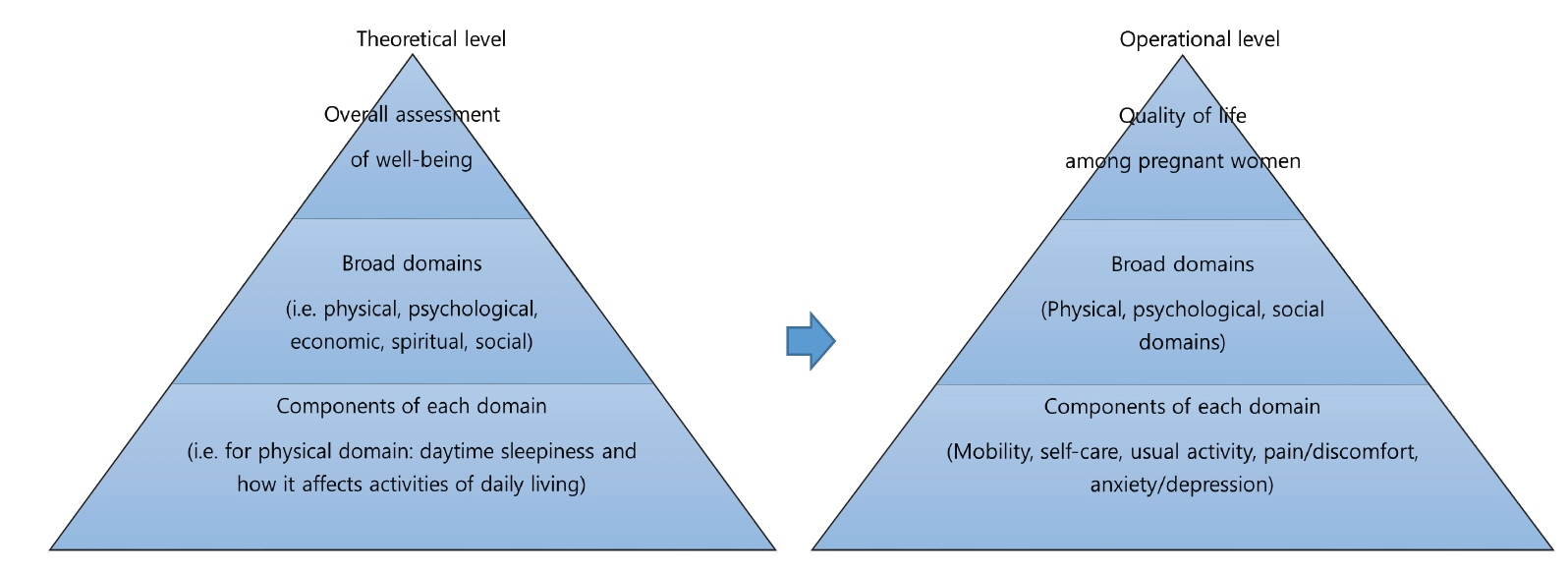

This study aimed to examine the effects of anxiety, depression, social support, and physical health status on the health-related quality of life of Korean pregnant women using Spilker’s quality of life model. Methods: This was a cross-sectional study with a correlational design. The participants included 166 pregnant women who were recruited via convenience sampling at two healthcare centers in South Korea. Questionnaires were collected from April 22 to May 29, 2023, in two cities in South Korea. The EuroQol-5D-3L, General Anxiety Disorder-7, Patient Health Questionnaire-2, Perceived Social Support through Others Scale-8, and EuroQol visual analog scale were used to assess the study variables. The t-test, Pearson correlation coefficients, and multiple regression tests were conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 26.0. Results: Statistically significant correlations were identified between the health-related quality of life of pregnant women and anxiety (r=.29, p<.001), depression (r=.31, p<.001), social support (r=–.34, p<.001), and physical health status (r=–.44, p<. 001). Physical health status (β=–.31, p<.001) and social support (β=–.21, p=.003) had the greatest effect on health-related quality of life (F=15.50, p<.001), with an explanatory power of 26.0%. Conclusion: The health-related quality of life of pregnant women was affected by social support and physical health status. This study demonstrated that physical health and social support promotion can improve the health-related quality of life of pregnant women. Healthcare providers should consider integrating physical health into social support interventions for pregnant women in the post-pandemic era.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Wekesa E, Askew I, Abuya T. Ambivalence in pregnancy intentions: the effect of quality of care and context among a cohort of women attending family planning clinics in Kenya. PLoS One. 2018; 13(1):e0190473. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190473.

Article2. Mei H, Li N, Li J, Zhang D, Cao Z, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosom Res. 2021; 149:110586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110586.

Article3. Vaccaro C, Mahmoud F, Aboulatta L, Aloud B, Eltonsy S. The impact of COVID-19 first wave national lockdowns on perinatal outcomes: a rapid review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21(1):676. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04156-y.

Article4. Lagadec N, Steinecker M, Kapassi A, Magnier AM, Chastang J, Robert S, et al. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1):455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4.

Article5. Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016; 34(7):645–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9.

Article6. Estebsari F, Kandi ZR, Bahabadi FJ, Filabadi ZR, Estebsari K, Mostafaei D. Health-related quality of life and related factors among pregnant women. J Educ Health Promot. 2020; 9:299. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_307_20.

Article7. Boutib A, Chergaoui S, Marfak A, Hilali A, Youlyouz-Marfak I. Quality of Life During Pregnancy from 2011 to 2021: Systematic Review. Int J Womens Health. 2022; 14:975–1005. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S361643.

Article8. Spilker B. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott-Raven;1996. p. 1–10.9. STROBE. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology [Internet]. Seoul: Author;2022. [cited 2023 Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.strobe-statement.org.10. Li J, Yin J, Waqas A, Huang Z, Zhang H, Chen M, et al. Quality of life in mothers with perinatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:734836. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.734836.

Article11. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009; 41(4):1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

Article12. Evans K, Fraser H, Uthman O, Osokogu O, Johnson S, Al-Khudairy L. The effect of mode of delivery on health-related quality-of-life in mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22(1):149. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04473-w.

Article13. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Article14. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999; 282(18):1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.18.1737.

Article15. Park JW. A study to development a scale of social support [dissertation]. Seoul: Yonsei University;1985. 127.16. Kim HJ, Kang J, Kim N. Development of short perceived social support through others scale (PSO-8): a Rasch analysis. J Hum Underst Couns. 2021; 42(1):51–70. https://doi.org/10.30593/JHUC.42.1.3.

Article17. Calou CG, Pinheiro AKB, Barbosa Castro RC, de Oliveira MF, de Souza Aquino P, Antezena FJ. Health related quality of life of pregnant women and associated factors: an integrative review. Health. 2014; 6(18):2375–2387. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2014.618273.

Article18. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001; 33(5):337–343. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890109002087.

Article19. Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The report of quality weighted health related quality of life. Seoul: Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2007.20. Franklin M, Enrique A, Palacios J, Richards D. Psychometric assessment of EQ-5D-5L and ReQoL measures in patients with anxiety and depression: construct validity and responsiveness. Qual Life Res. 2021; 30(9):2633–2647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02833-1.

Article21. Lau Y, Yin L. Maternal, obstetric variables, perceived stress and health-related quality of life among pregnant women in Macao, China. Midwifery. 2011; 27(5):668–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.02.008.

Article22. Montoya Arizabaleta AV, Orozco Buitrago L, Aguilar de Plata AC, Mosquera Escudero M, Ramirez-Velez R. Aerobic exercise during pregnancy improves health-related quality of life: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2010; 56(4):253–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1836-9553(10)70008-4.

Article23. Vallim AL, Osis MJ, Cecatti JG, Baciuk ÉP, Silveira C, Cavalcante SR. Water exercises and quality of life during pregnancy. Reprod Health. 2011; 8:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-14.

Article24. Boutib A, Chergaoui S, Azizi A, Saad EM, Hilali A, Youlyouz Marfak I, et al. Health-related quality of life during three trimesters of pregnancy in Morocco: cross-sectional pilot study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023; 57:101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101837.

Article25. Wang B, Liu Y, Qian J, Parker SK. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: a work design perspective. Appl Psychol. 2021; 70(1):16–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290.

Article26. Luo Y, Zhang K, Huang M, Qiu C. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022; 17(3):e0265021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265021.

Article27. Blustein DL, Kenny ME, Autin K, Duffy R. The psychology of working in practice: a theory of change for a new era. Career Dev Q. 2019; 67(3):236–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12193.

Article28. Camacho EM, Shields GE, Chew-Graham CA, Eisner E, Gilbody S, Littlewood E, et al. Generating EQ-5D-3L health utility scores from the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: a perinatal mapping study. Eur J Health Econ. 2023; Apr. 24. [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-023-01589-4.

Article29. Janssen MF, Szende A, Cabases J, Ramos-Goñi JM, Vilagut G, König HH. Population norms for the EQ-5D-3L: a cross-country analysis of population surveys for 20 countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2019; 20(2):205–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0955-5.

Article30. Bauer AE, Guintivano J, Krohn H, Sullivan PF, Meltzer-Brody S. The longitudinal effects of stress and fear on psychiatric symptoms in mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2022; 25(6):1067–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01265-1.

Article31. COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021; 398(10312):1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on depression during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study

- Influencing Factors on Health-related Quality of Life among Japanese Middle-aged Marriage-based Immigrant Women in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Study

- A Study on the Relationship between Social Support, Health Promoting Behaviors and Depression among Unmarried Pregnant Women

- Effects of Frailty on Health-related Quality of Life of Rural Community-dwelling Elderly: Mediating and Moderating Effects of Fall-Related Efficacy and Social Support

- Effects of Intergenerational Social Support Exchange and Self-efficacy on Level of Depression among Elderly Women