Intest Res.

2023 Apr;21(2):177-188. 10.5217/ir.2023.00003.

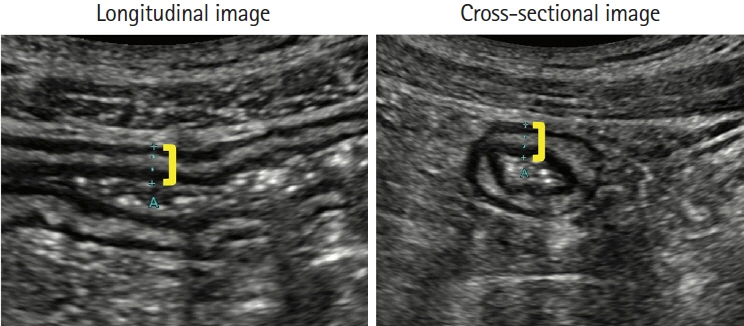

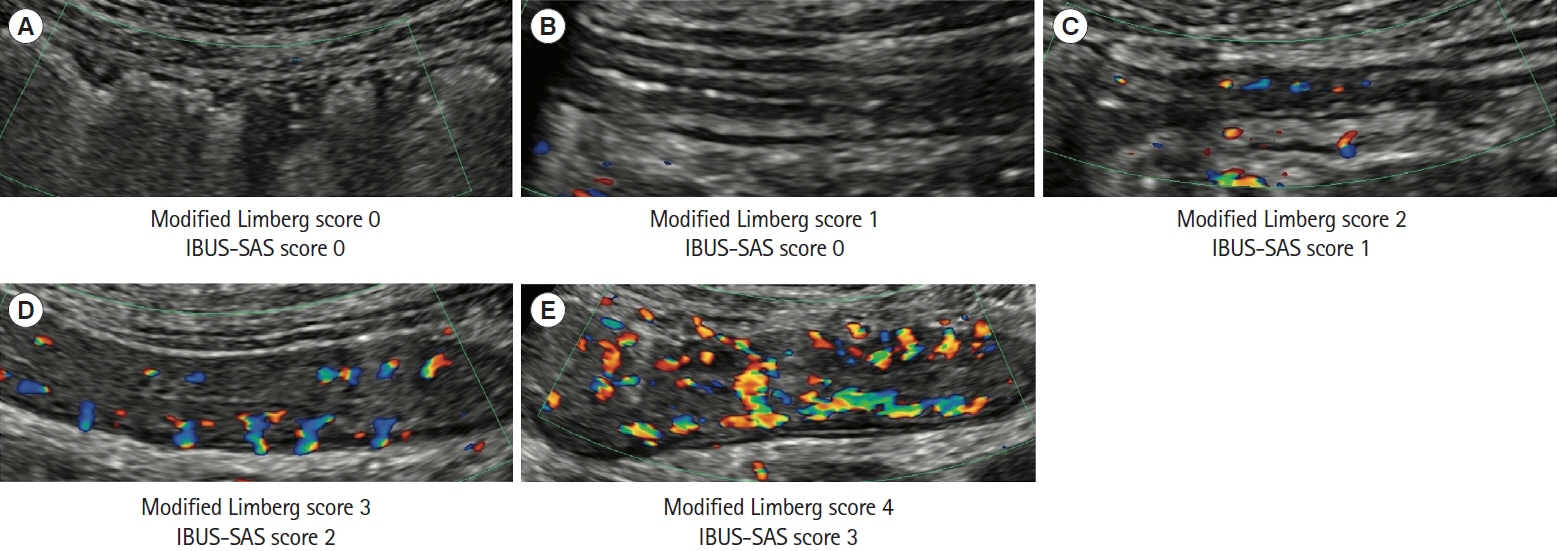

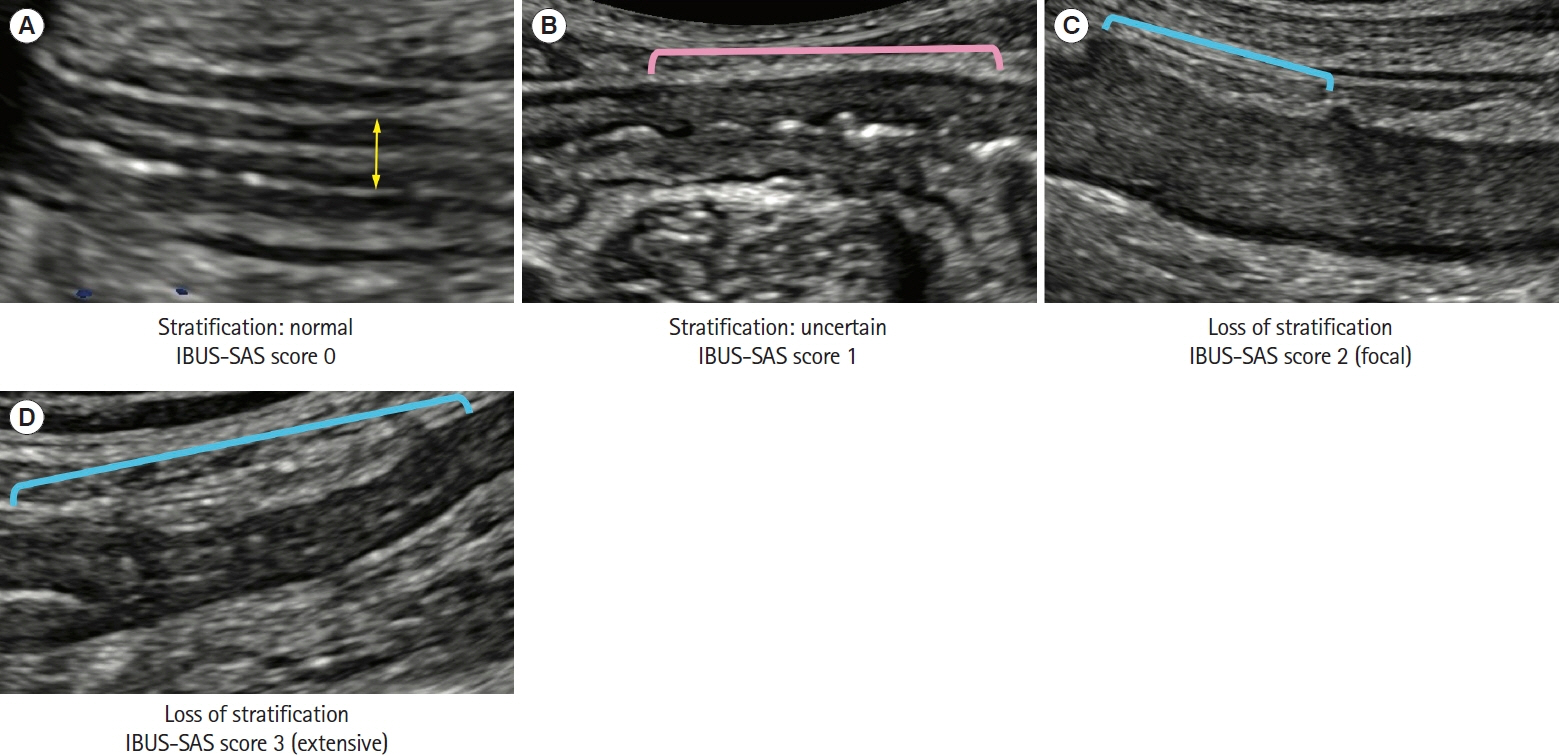

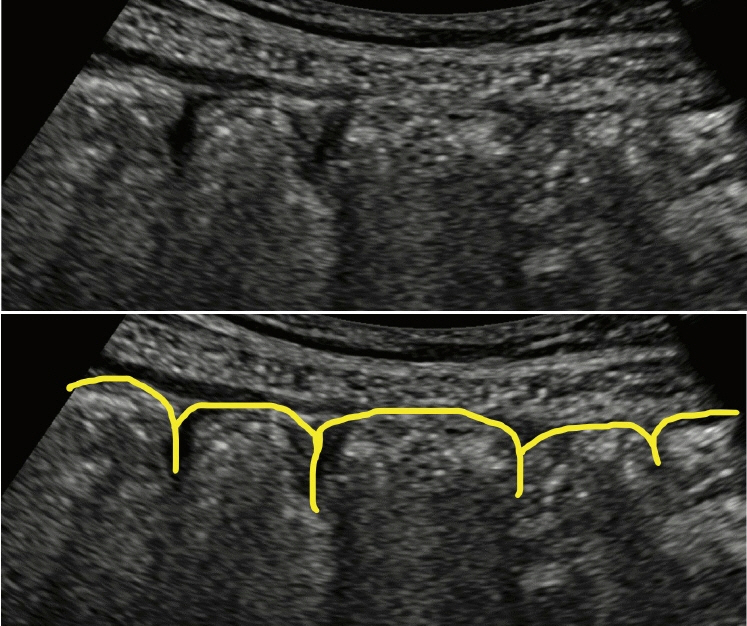

First aid with color atlas for the use of intestinal ultrasound for inflammatory bowel disease in daily clinical practice

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kyorin University School of Medicine, Mitaka, Japan

- KMID: 2541890

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2023.00003

Abstract

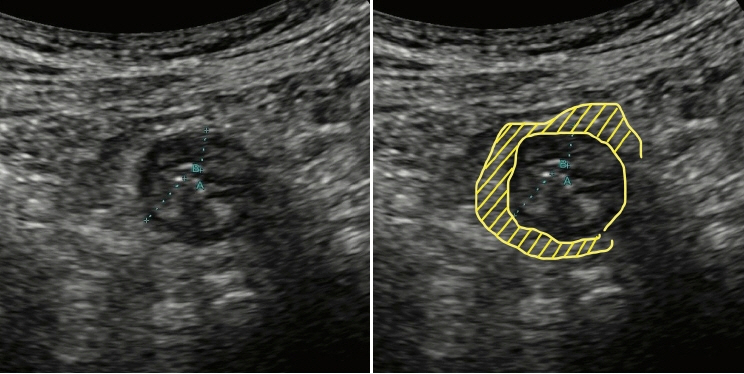

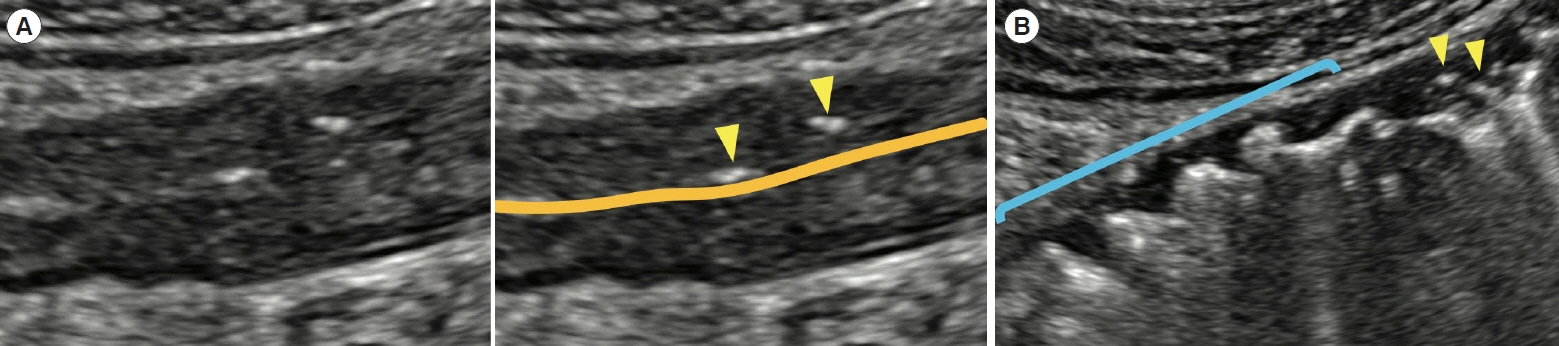

- Intestinal ultrasound (IUS) is a promising modality for the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and has the potential to particularly contribute in monitoring disease activity, an advantage crucial for optimizing the therapeutic strategy. While many IBD physicians appreciate and are interested in the use of IUS for IBD, currently only a limited number of facilities can employ this examination in daily clinical practice. A lack of guidance is one of the major barriers to introducing this procedure. Standardized protocols and assessment criteria are needed such that IUS for IBD can be considered a feasible, reliable examination in clinical practice, and multicenter clinical studies can be conducted for further clinical evidence of the application of IUS in IBD for best patient care. In this article, we provide an overview of how to start IUS for IBD and introduce basic procedures. Furthermore, IUS images from our practice are provided as a color atlas for understanding sonographic findings and scoring systems. We anticipate this “first aid” article will be helpful to promote IUS for IBD in daily practice.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Windsor JW, Kaplan GG. Evolving epidemiology of IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019; 21:40.

Article2. Olén O, Askling J, Sachs MC, et al. Mortality in adult-onset and elderly-onset IBD: a nationwide register-based cohort study 1964-2014. Gut. 2020; 69:453–461.

Article3. Tsai L, Ma C, Dulai PS, et al. Contemporary risk of surgery in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohorts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 19:2031–2045.e11.

Article4. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021; 160:1570–1583.

Article5. Benitez JM, Meuwis MA, Reenaers C, Van Kemseke C, Meunier P, Louis E. Role of endoscopy, cross-sectional imaging and biomarkers in Crohn’s disease monitoring. Gut. 2013; 62:1806–1816.

Article6. Kucharzik T, Tielbeek J, Carter D, et al. ECCO-ESGAR topical review on optimizing reporting for cross-sectional imaging in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022; 16:523–543.

Article7. Maconi G, Nylund K, Ripolles T, et al. EFSUMB recommendations and clinical guidelines for intestinal ultrasound (GIUS) in inflammatory bowel diseases. Ultraschall Med. 2018; 39:304–317.

Article8. Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13:144–164.

Article9. Sturm A, Maaser C, Calabrese E, et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD part 2: IBD scores and general principles and technical aspects. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13:273–284.

Article10. Ilvemark JF, Hansen T, Goodsall TM, et al. Defining transabdominal intestinal ultrasound treatment response and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and expert consensus statement. J Crohns Colitis. 2022; 16:554–580.

Article11. De Voogd F, Joshi H, Van Wassenaer E, Bots S, D’Haens G, Gecse K. Intestinal ultrasound to evaluate treatment response during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022; 28:1045–1052.

Article12. Allocca M, Fiorino G, Bonifacio C, et al. Comparative accuracy of bowel ultrasound versus magnetic resonance enterography in combination with colonoscopy in assessing Crohn’s disease and guiding clinical decision-making. J Crohns Colitis. 2018; 12:1280–1287.

Article13. Kucharzik T, Wittig BM, Helwig U, et al. Use of intestinal ultrasound to monitor Crohn’s disease activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 15:535–542.

Article14. Maaser C, Petersen F, Helwig U, et al. Intestinal ultrasound for monitoring therapeutic response in patients with ulcerative colitis: results from the TRUST&UC study. Gut. 2020; 69:1629–1636.

Article15. Kucharzik T, Wilkens R, D’Agostino MA, et al. Early ultrasound response and progressive transmural remission after treatment with ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023; 21:153–163.e12.16. Ilvemark JF, Wilkens R, Thielsen P, et al. Early intestinal ultrasound predicts intravenous corticosteroid response in hospitalised patients with severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2022; 16:1725–1734.

Article17. Sævik F, Eriksen R, Eide GE, Gilja OH, Nylund K. Development and validation of a simple ultrasound activity score for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021; 15:115–124.

Article18. Allocca M, Filippi E, Costantino A, et al. Milan ultrasound criteria are accurate in assessing disease activity in ulcerative colitis: external validation. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021; 9:438–442.

Article19. De Voogd F, Wilkens R, Gecse K, et al. A reliability study: strong inter-observer agreement of an expert panel for intestinal ultrasound in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2021; 15:1284–1290.

Article20. Sagami S, Kobayashi T, Aihara K, et al. Transperineal ultrasound predicts endoscopic and histological healing in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020; 51:1373–1383.

Article21. Miyoshi J, Ozaki R, Yonezawa H, et al. Ratio of submucosal thickness to total bowel wall thickness as a new sonographic parameter to estimate endoscopic remission of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2022; 57:82–89.

Article22. Sagami S, Kobayashi T, Miyatani Y, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound for evaluation of colorectal segments in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 19:908–921.e6.

Article23. Maconi G, Tonolini M, Monteleone M, et al. Transperineal perineal ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of perianal Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:2737–2743.

Article24. Sagami S, Kobayashi T, Aihara K, et al. Early improvement in bowel wall thickness on transperineal ultrasonography predicts treatment success in active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022; 55:1320–1329.

Article25. Novak KL, Nylund K, Maaser C, et al. Expert consensus on optimal acquisition and development of the international bowel ultrasound segmental activity score [IBUS-SAS]: a reliability and inter-rater variability study on intestinal ultrasonography in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021; 15:609–616.

Article26. Allocca M, Fiorino G, Bonovas S, et al. Accuracy of humanitas ultrasound criteria in assessing disease activity and severity in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018; 12:1385–1391.

Article27. Bots S, Nylund K, Löwenberg M, Gecse K, D’Haens G. Intestinal ultrasound to assess disease activity in ulcerative colitis: development of a novel UC-ultrasound index. J Crohns Colitis. 2021; 15:1264–1271.

Article28. Limberg B. Diagnosis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease by ultrasonography. Z Gastroenterol. 1999; 37:495–508.29. Gasche C, Moser G, Turetschek K, Schober E, Moeschl P, Oberhuber G. Transabdominal bowel sonography for the detection of intestinal complications in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1999; 44:112–117.

Article30. Rieder F, Bettenworth D, Ma C, et al. An expert consensus to standardise definitions, diagnosis and treatment targets for anti-fibrotic stricture therapies in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018; 48:347–357.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Crohn’s disease at radiological imaging: focus on techniques and intestinal tract

- Can vitamin D supplementation help control inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease beyond its classical role in bone health?

- Intestinal Behcet's Disease: A True Inflammatory Bowel Disease or Merely an Intestinal Complication of Systemic Vasculitis?

- Artificial intelligence in inflammatory bowel disease: implications for clinical practice and future directions

- The Use of Transabdominal Ultrasound in Inflammatory Bowel Disease