Clin Endosc.

2023 Mar;56(2):203-213. 10.5946/ce.2022.087.

Methylene blue chromoendoscopy is more useful in detection of intestinal metaplasia in the stomach than mucosal pit pattern or vessel evaluation and predicts advanced Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia stages

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of General Pathomorphology, Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland

- 2Department of Gastroenterology and Internal Medicine, Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland

- KMID: 2540738

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.087

Abstract

- Background/Aims

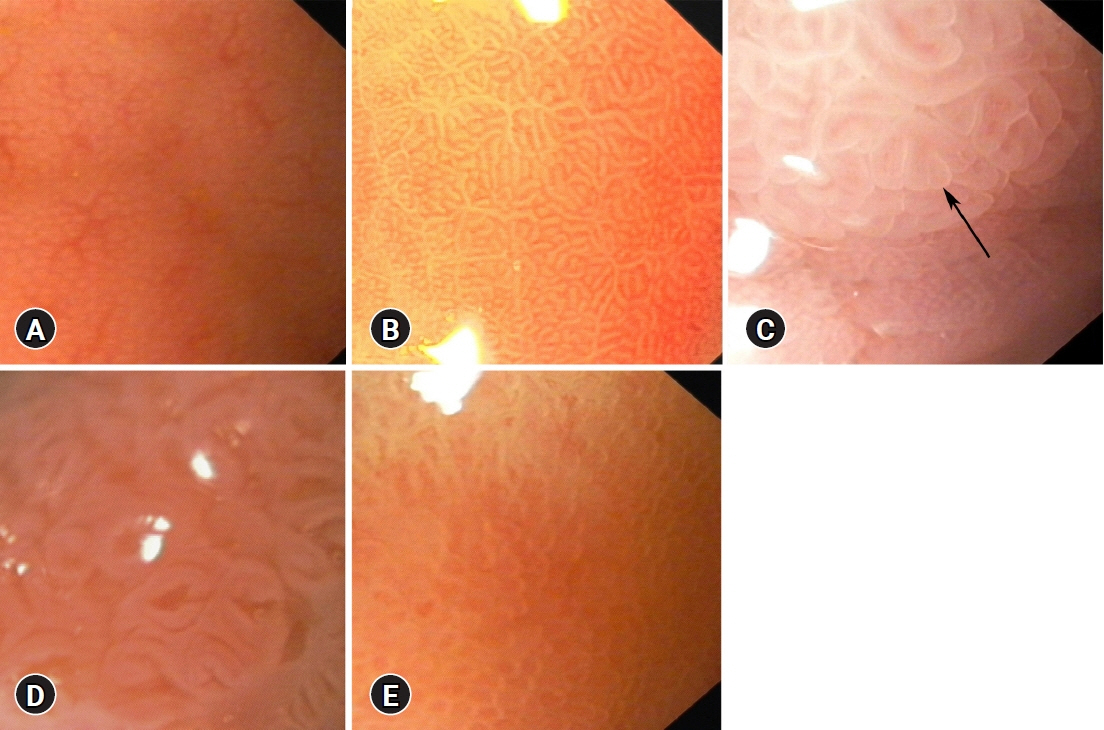

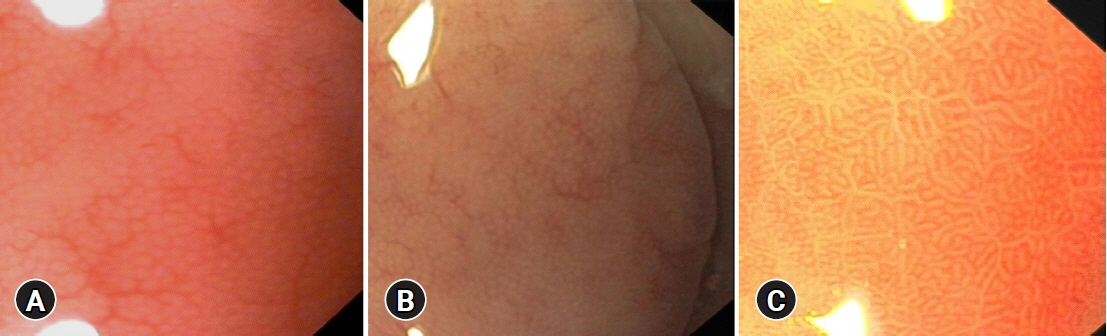

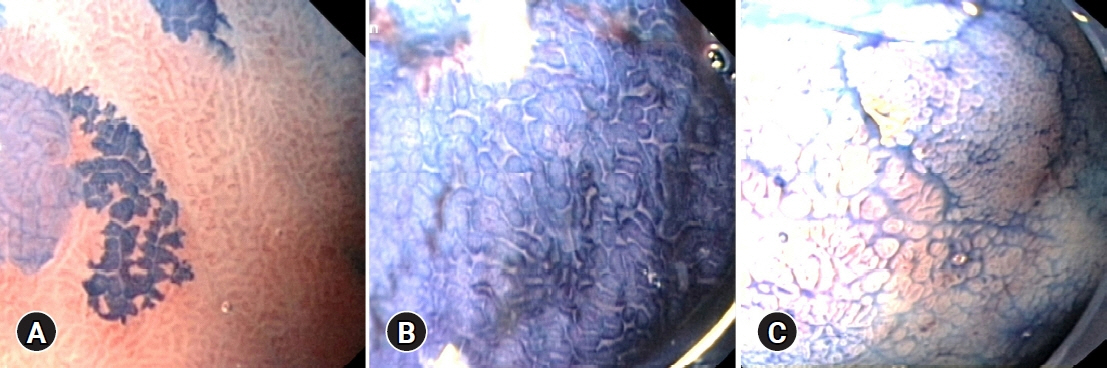

Intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the stomach is a precancerous condition that is often not visible during conventional endoscopy. Hence, we evaluated the utility of magnification endoscopy and methylene blue (MB) chromoendoscopy to detect IM.

Methods

We estimated the percentage of gastric mucosa surface staining with MB, mucosal pit pattern, and vessel visibility and correlated it with the presence of IM and the percentage of metaplastic cells in histology, similar to the Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia (OLGIM) stage.

Results

IM was found in 25 of 33 (75.8%) patients and in 61 of 135 biopsies (45.2%). IM correlated with positive MB staining (p<0.001) and other than dot pit patterns (p=0.015). MB staining indicated IM with better accuracy than the pit pattern or vessel evaluation (71.7% vs. 60.5% and 49.6%, respectively). At a cut-off point of 16.5% for the MB-stained gastric surface, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of chromoendoscopy in the detection of advanced OLGIM stages were 88.9%, 91.7%, and 90.9%, respectively. The percentage of metaplastic cells detected on histology was the strongest predictor of positive MB staining.

Conclusions

MB chromoendoscopy can serve as a screening method for detecting advanced OLGIM stages. MB mainly stains IM areas with a high concentration of metaplastic cells.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019; 144:1941–1953.2. Vannella L, Lahner E, Osborn J, et al. Risk factors for progression to gastric neoplastic lesions in patients with atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 31:1042–1050.3. Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019; 51:365–388.4. Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, et al. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 71:1150–1158.5. Filipe MI, Muñoz N, Matko I, et al. Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: a cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer. 1994; 57:324–329.6. Mera RM, Bravo LE, Camargo MC, et al. Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection as a determinant of progression of gastric precancerous lesions: 16-year follow-up of an eradication trial. Gut. 2018; 67:1239–1246.7. Peitz U, Malfertheiner P. Chromoendoscopy: from a research tool to clinical progress. Dig Dis. 2002; 20:111–119.8. Dinis-Ribeiro M, da Costa-Pereira A, Lopes C, et al. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the diagnosis of gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003; 57:498–504.9. Wasielica-Berger J, Baniukiewicz A, Wroblewski E, et al. Magnification endoscopy and chromoendoscopy in evaluation of specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2011; 56:1987–1995.10. Areia M, Amaro P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, et al. External validation of a classification for methylene blue magnification chromoendoscopy in premalignant gastric lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:1011–1018.11. Yang JM, Chen L, Fan YL, et al. Endoscopic patterns of gastric mucosa and its clinicopathological significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2003; 9:2552–2556.12. Nakagawa S, Kato M, Shimizu Y, et al. Relationship between histopathologic gastritis and mucosal microvascularity: observations with magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003; 58:71–75.13. Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015; 64:1353–1367.14. Mahawongkajit P, Kanlerd A. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing simethicone, N-acetylcysteine, sodium bicarbonate and peppermint for visualization in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2021; 35:303–308.15. Davies J, Burke D, Olliver JR, et al. Methylene blue but not indigo carmine causes DNA damage to colonocytes in vitro and in vivo at concentrations used in clinical chromoendoscopy. Gut. 2007; 56:155–156.16. Dinis-Ribeiro M, Moreira-Dias L. There is no clinical evidence of consequences after methylene blue chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:1209.17. Repici A, Ciscato C, Wallace M, et al. Evaluation of genotoxicity related to oral methylene blue chromoendoscopy. Endoscopy. 2018; 50:1027–1032.18. Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Lage J, et al. A multicenter prospective study of the real-time use of narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of premalignant gastric conditions and lesions. Endoscopy. 2016; 48:723–730.19. Esposito G, Pimentel-Nunes P, Angeletti S, et al. Endoscopic grading of gastric intestinal metaplasia (EGGIM): a multicenter validation study. Endoscopy. 2019; 51:515–521.20. Cho JH, Jeon SR, Jin SY. Clinical applicability of gastroscopy with narrow-band imaging for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori gastritis, precancerous gastric lesion, and neoplasia. World J Clin Cases. 2020; 8:2902–2916.21. Jang JY. The past, present, and future of image-enhanced endoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2015; 48:466–475.22. Kiesslich R, Jung M, DiSario JA, et al. Perspectives of chromo and magnifying endoscopy: how, how much, when, and whom should we stain? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004; 38:7–13.23. Sobrino-Cossío S, Teramoto-Matsubara O, Emura F, et al. Usefulness of optical enhancement endoscopy combined with magnification to improve detection of intestinal metaplasia in the stomach. Endosc Int Open. 2022; 10:E441–E447.24. Yagi K, Honda H, Yang JM, et al. Magnifying endoscopy in gastritis of the corpus. Endoscopy. 2005; 37:660–666.25. Anagnostopoulos GK, Yao K, Kaye P, et al. High-resolution magnification endoscopy can reliably identify normal gastric mucosa, Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis, and gastric atrophy. Endoscopy. 2007; 39:202–207.26. Tahara T, Tahara S, Tuskamoto T, et al. Magnifying NBI patterns of gastric mucosa after Helicobacter pylori eradication and its potential link to the gastric cancer risk. Dig Dis Sci. 2017; 62:2421–2427.27. Filipe MI, Potet F, Bogomoletz WV, et al. Incomplete sulphomucin-secreting intestinal metaplasia for gastric cancer: preliminary data from a prospective study from three centres. Gut. 1985; 26:1319–1326.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Endoscopic Classification of Intestinal Metaplasia

- The Study of the Positivity of Helicobacter pylori in the Intestinal Metaplasia Detected by Methylene Blue Chromoendoscopy and Histology

- Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to areas of type II intestinal metaplasia in Korean gastric mucosa

- Methylene Blue Solution-induced Acute Esophageal Mucosal Injury: First Case Report

- Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to Areas of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia by the Genta Stain