Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2023 Mar;66(2):69-75. 10.5468/ogs.22227.

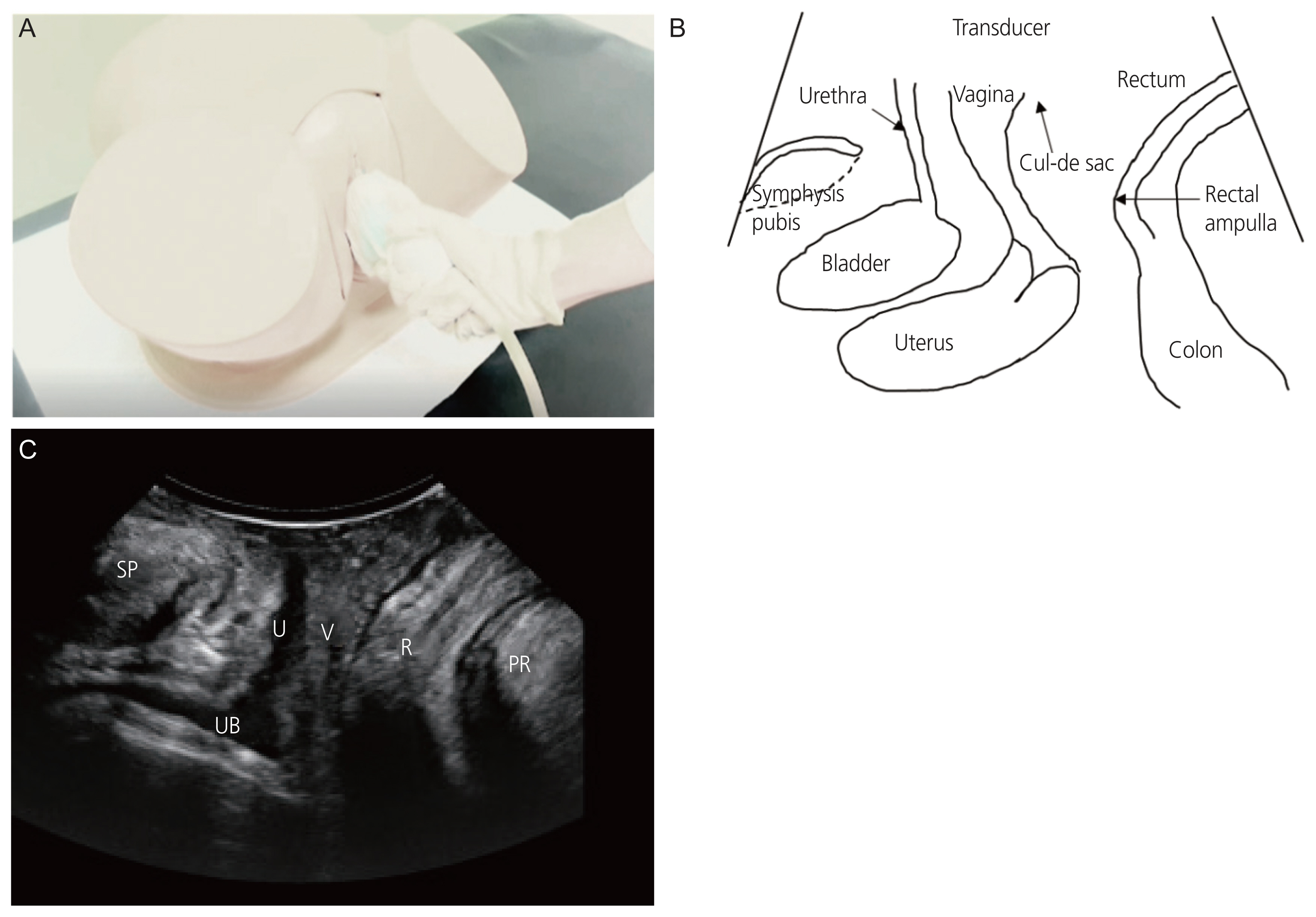

Translabial ultrasound for pelvic organ prolapse

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Faisal Medical City for Southern Regions, Al Marooj, Abha, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2540475

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.22227

Abstract

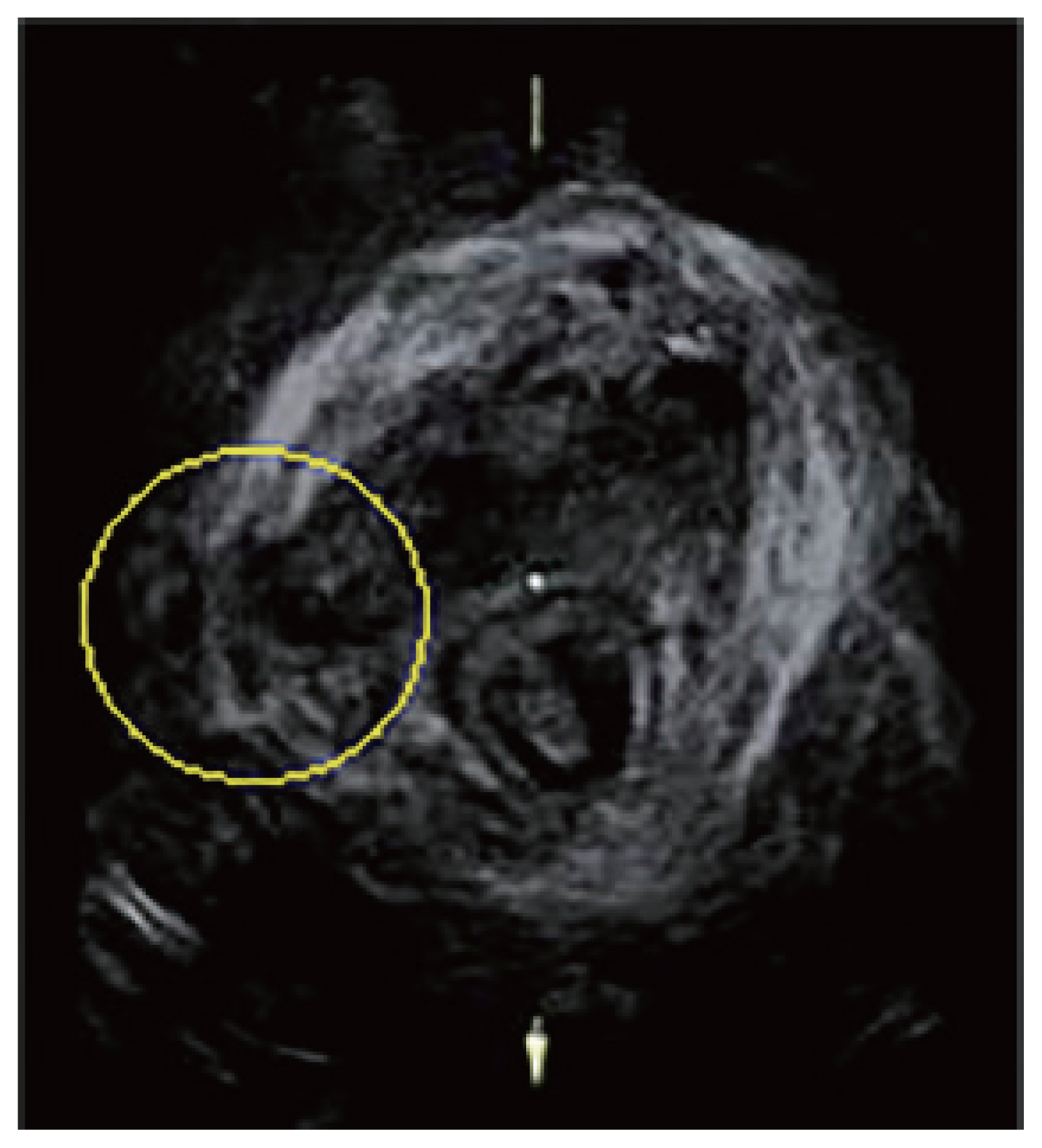

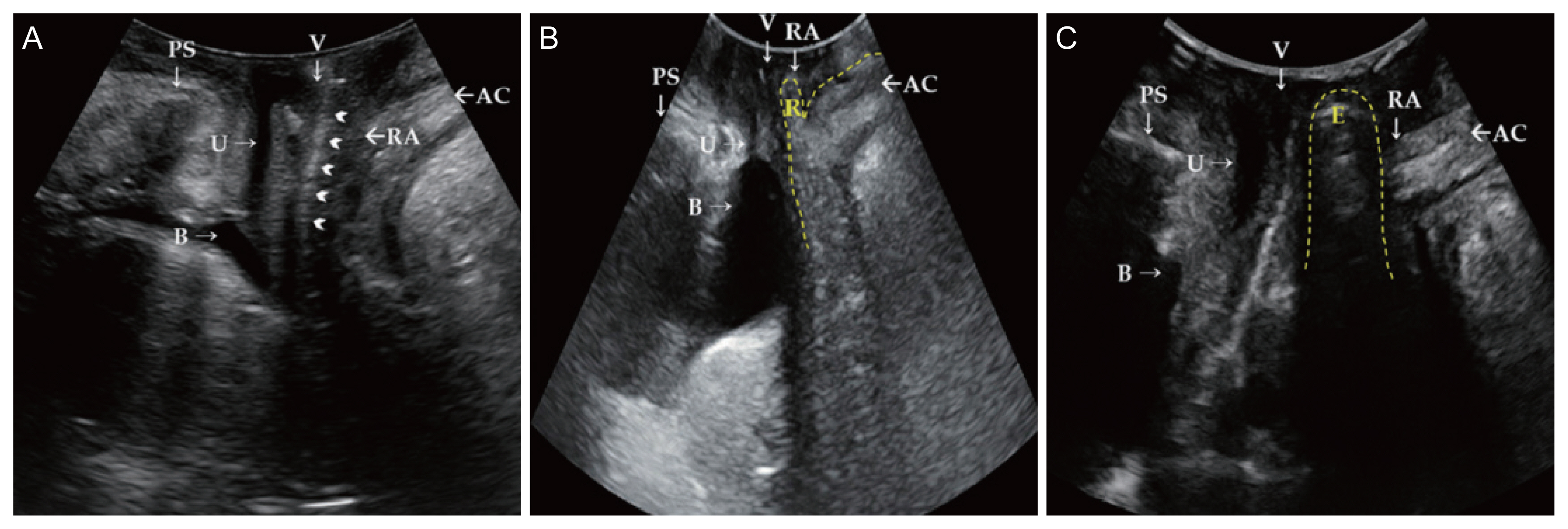

- Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a significant public health concern in women and a common cause of gynecological surgery in elderly women. The prevalence of POP has increased with an increase in the aging population. POP is usually diagnosed based on pelvic examination. However, an imaging study may be necessary for more accurate diagnosis. Translabial ultrasound (TLUS) was used to assess diverse types of POP, particularly posterior-compartment POP. It is beneficial to distinguish between true and false rectocele, and detect the rectocele as clinically apparent. TLUS can also establish whether the underlying cause is a problem of the rectovaginal septum, perineal hypermobility, or isolated enterocele. TLUS also plays a role in differentiating POP from conditions that mimic POP. It is a simple, inexpensive, and non-harmful diagnostic modality that is appropriate for most gynecologic clinics.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Shek KL, Dietz HP. Assessment of pelvic organ prolapse: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 48:681–92.2. Nam G, Lee SR, Kim SH, Chae HD. Importance of translabial ultrasound for the diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse and its correlation with the POP-Q examination: analysis of 363 cases. J Clin Med. 2021; 10:4267.3. Brown JS, Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van den Eeden S, Vittinghoff E. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States, 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 186:712–6.4. Oh S, Namkung HR, Yoon HY, Lee SY, Jeon MJ. Factors associated with unsuccessful pessary fitting and reasons for discontinuation in Korean women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022; 65:94–9.5. Kim BH, Lee SB, Na ED, Kim HC. Correlation between obesity and pelvic organ prolapse in Korean women. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020; 63:719–25.6. Oh S, Namkung HR, Yoon HY, Lee SY, Jeon MJ. Factors associated with unsuccessful pessary fitting and reasons for discontinuation in Korean women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022; 65:94–9.7. Kim JH, Lee SY, Chae HD, Shin YK, Lee SR, Kim SH. Outcomes of vaginal hysterectomy combined with anterior and posterior colporrhaphy for pelvic organ prolapse: a single center retrospective study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022; 65:74–83.8. Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:1096–100.9. Løwenstein E, Ottesen B, Gimbel H. Incidence and lifetime risk of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Denmark from 1977 to 2009. Int Urogynecol J. 2015; 26:49–55.10. Digesu GA, Chaliha C, Salvatore S, Hutchings A, Khullar V. The relationship of vaginal prolapse severity to symptoms and quality of life. BJOG. 2005; 112:971–6.11. Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 104:489–97.12. Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:1096–100.13. Oliphant SS, Jones KA, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Trends over time with commonly performed obstetric and gynecologic inpatient procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:926–31.14. Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114:1278–83.15. Kim SR, Suh DH, Kim W, Jeon MJ. Current techniques used to perform surgery for anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapse in South Korea. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022; 65:273–8.16. Yuk JS, Lee JH, Hur JY, Shin JH. The prevalence and treatment pattern of clinically diagnosed pelvic organ prolapse: a Korean National Health Insurance database-based cross-sectional study 2009–2015. Sci Rep. 2018; 8:1334.17. Dietz HP, Steensma AB. Posterior compartment prolapse on two-dimensional and three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hypermobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 26:73–7.18. Salsi G, Cataneo I, Dodaro G, Rizzo N, Pilu G, Sanz Gascón M, et al. Three-dimensional/four-dimensional transperineal ultrasound: clinical utility and future prospects. Int J Womens Health. 2017; 9:643–56.19. Dietz HP. Pelvic floor trauma following vaginal delivery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 18:528–37.20. DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Kearney R, Guire K, Miller JM, et al. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109:295–302.21. Shek KL, Dietz HP. The effect of childbirth on hiatal dimensions. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113:1272–8.22. Dietz HP. Pelvic floor ultrasound: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 202:321–34.23. Dietz HP, Haylen BT, Broome J. Ultrasound in the quantification of female pelvic organ prolapse. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 18:511–4.24. DeLancey JO. The hidden epidemic of pelvic floor dysfunction: achievable goals for improved prevention and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192:1488–95.25. Dietz HP. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part II: three-dimensional or volume imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 23:615–25.26. Dietz HP, Shek C, Clarke B. Biometry of the pubovisceral muscle and levator hiatus by three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 25:580–5.27. Dietz HP, Steensma AB. The prevalence of major abnormalities of the levator ani in urogynaecological patients. BJOG. 2006; 113:225–30.28. Siafarikas F, Staer-Jensen J, Braekken IH, Bø K, Engh ME. Learning process for performing and analyzing 3D/4D transperineal ultrasound imaging and interobserver reliability study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 41:312–7.29. Majida M, Braekken IH, Umek W, Bø K, Saltyte Benth J, Ellstrøm Engh M. Interobserver repeatability of three- and four-dimensional transperineal ultrasound assessment of pelvic floor muscle anatomy and function. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 33:567–73.30. van Veelen GA, Schweitzer KJ, van der Vaart CH. Reliability of pelvic floor measurements on three- and four-dimensional ultrasound during and after first pregnancy: implications for training. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 42:590–5.31. Chen R, Song Y, Jiang L, Hong X, Ye P. The assessment of voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction by three-dimensional transperineal ultrasonography. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011; 284:931–6.32. van Delft K, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Pelvic floor muscle contractility: digital assessment vs transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 45:217–22.33. van Delft KW, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Shobeiri SA, Kluivers KB. Agreement between palpation and transperineal and endovaginal ultrasound in the diagnosis of levator ani avulsion. Int Urogynecol J. 2015; 26:33–9.34. Gao Y, Zhao Z, Yang Y, Zhang M, Wu J, Miao Y. Diagnostic value of pelvic floor ultrasonography for diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2020; 31:15–33.35. Nam G, Lee SR, Eum HR, Kim SH, Chae HD, Kim GJ. A huge hemorrhagic epidermoid cyst of the perineum with hypoechoic semisolid ultrasonographic feature mimicking scar endometriosis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021; 57:276.36. Nam G, Lee SR, Choi S. Clitoromegaly, vulvovaginal hemangioma mimicking pelvic organ prolapse, and heavy menstrual bleeding: gynecologic manifestations of klippel-trénaunay syndrome. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021; 57:366.37. Lee SR, Lim YM, Jeon JH, Park MH. Diagnosis of urethral diverticulum mimicking pelvic organ prolapse with translabial ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 217:482.38. Chang OH, Davidson ERW, Thomas TN, Paraiso MFR, Ferrando CA. Does concurrent posterior repair for an asymptomatic rectocele reduce the risk of surgical failure in patients undergoing sacrocolpopexy? Int Urogynecol J. 2020; 31:2075–80.39. Arunachalam D, Hale DS, Heit MH. Posterior compartment surgery provides no differential benefit for defecatory symptoms before or after concomitant mesh-augmented apical suspension. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018; 24:183–7.40. Dietz HP. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part I: two-dimensional aspects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 23:80–92.41. Beer-Gabel M, Teshler M, Schechtman E, Zbar AP. Dynamic transperineal ultrasound vs. defecography in patients with evacuatory difficulty: a pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004; 19:60–7.42. Braga A, Soave I, Caccia G, Regusci L, Ruggeri G, Pitaku I, et al. What is this vaginal bulge? An atypical case of vaginal paraurethral leiomyoma. A case report and literature systematic review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021; 50:101822.43. Rechi-Sierra K, Sánchez-Ballester F, García-Ibáñez J, Pardo-Duarte P, Flores-Delatorre M, Monzó-Cataluña A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate anterior pelvic prolapse: H line is the key. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021; 40:1042–7.