Anesth Pain Med.

2022 Oct;17(4):429-433. 10.17085/apm.22134.

Educational value of spinal injection therapy videos in Korean YouTube for back pain patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2535342

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.22134

Abstract

- Background

YouTube, the largest online video platform, has become increasingly popular as a source of health information to patients. The aim of the study was to assess whether Korean patients were well informed about spinal injection from YouTube.

Methods

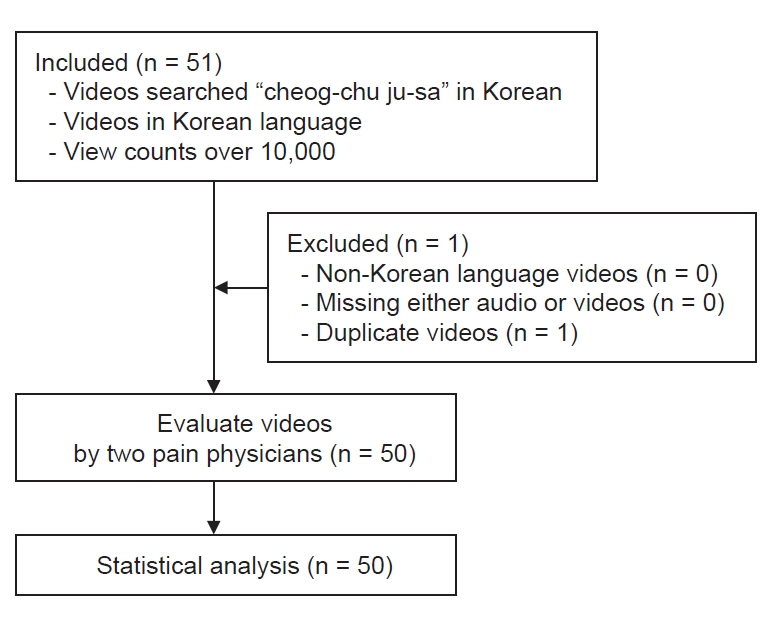

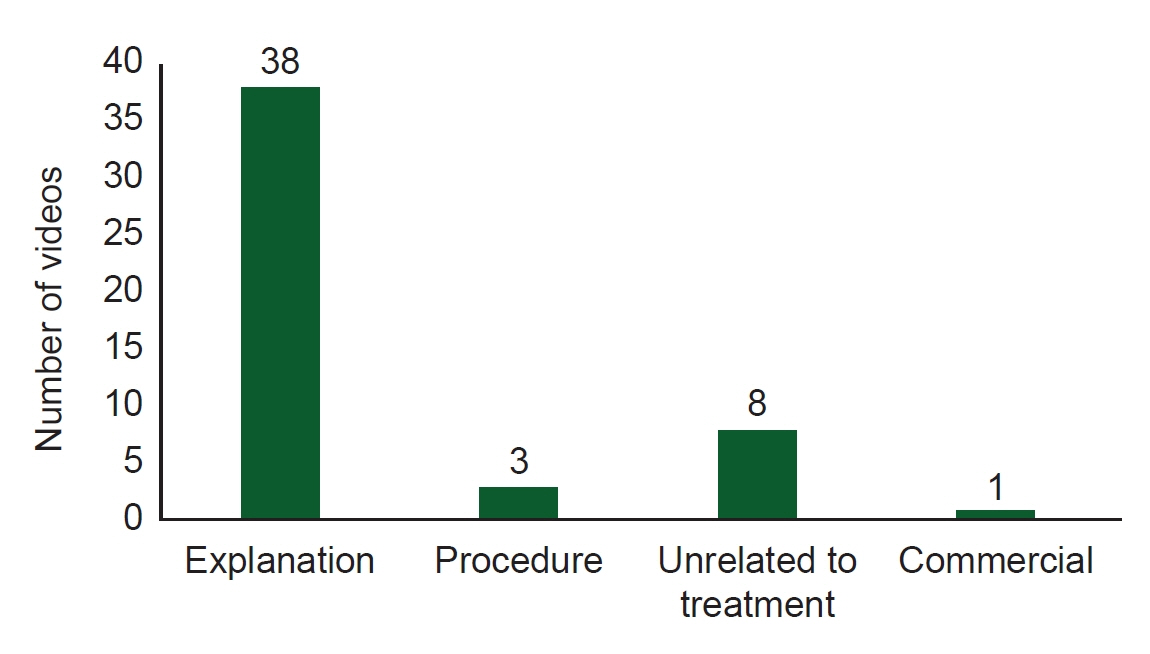

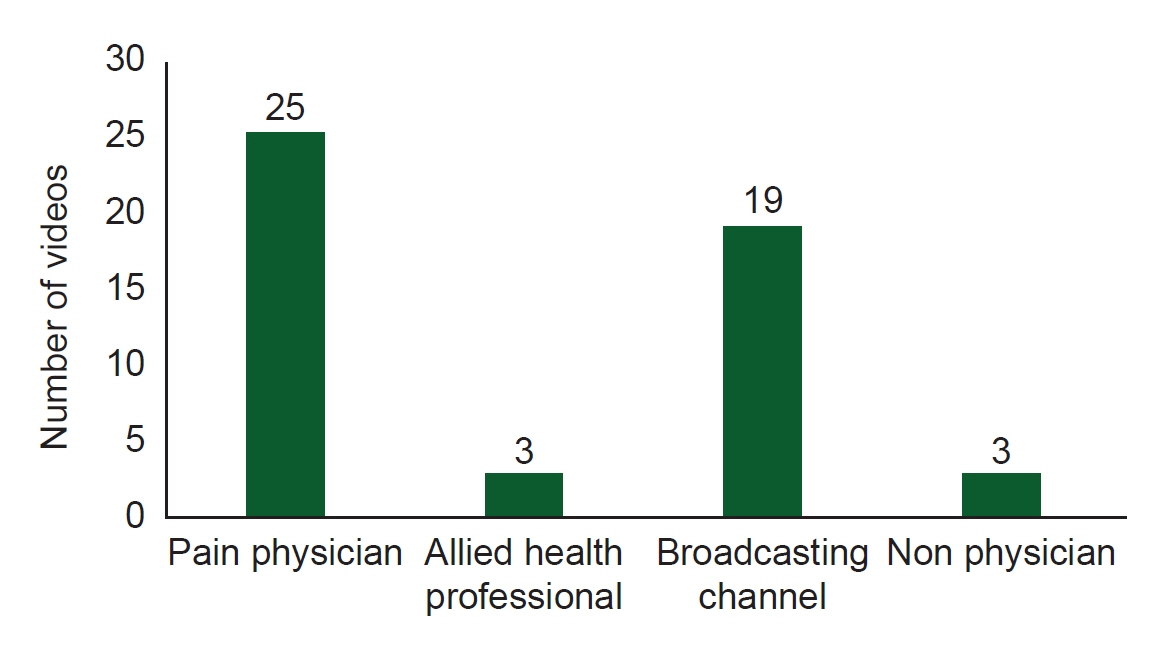

Search for the keyword “cheog-chu ju-sa” in Korean language was done, and the quality of the 51 videos with the highest number of views was evaluated independently by two pain management doctors.

Results

The averages of global quality scores evaluated by the two doctors were 3.0 and 3.5 and modified DISCERN (mDISCERN) scores were 2.8 and 3.0, respectively. The Kappa statistic between the two doctors’ scores was 0.285 and 0.417.

Conclusions

The percentage of low-quality videos with a global quality score of 2 or less is 18–36%, which indicated that these videos might provide inaccurate or misleading medical information to the patient. Pain clinic doctors should be wary of medically misleading information available on online platforms, such as YouTube, and strive to create and distribute professional quality educational materials.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Son KM, Cho NH, Lim SH, Kim HA. Prevalence and risk factor of neck pain in elderly Korean community residents. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:680–6.

Article2. Koh MJ, Park SY, Woo YS, Kang SH, Park SH, Chun HJ, et al. Assessing the prevalence of recurrent neck and shoulder pain in Korean high school male students: a cross-sectional observational study. Korean J Pain. 2012; 25:161–7.

Article3. Baek SR, Lim JY, Lim JY, Park JH, Lee JJ, Lee SB, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in an elderly Korean population: results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010; 51:e46–51.

Article4. Cho NH, Jung YO, Lim SH, Chung CK, Kim HA. The prevalence and risk factors of low back pain in rural community residents of Korea. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012; 37:2001–10.

Article5. Chang MC. Conservative treatments frequently used for chronic pain patients in clinical practice: a literature review. Cureus. 2020; 12:e9934.

Article6. Rabinovitch DL, Peliowski A, Furlan AD. Influence of lumbar epidural injection volume on pain relief for radicular leg pain and/or low back pain. Spine J. 2009; 9:509–17.

Article7. Lievre JA, Bloch-Michel H, Pean G, Uro J. L'hydrocortisone en injection locale. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1953; 20:310–1.8. Finlayson RJ, Gupta G, Alhujairi M, Dugani S, Tran DQ. Cervical medial branch block: a novel technique using ultrasound guidance. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012; 37:219–23.9. Ghormley RK. Low back pain: with special reference to the articular facets, with presentation of an operative procedure. JAMA. 1933; 101:1773–7.10. Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009; 11:e4.

Article11. Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Greenberg-Worisek AJ, Allen SV, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Online health information seeking among US adults: measuring progress toward a healthy people 2020 objective. Public Health Rep. 2019; 134:617–25.

Article12. Crocco AG, Villasis-Keever M, Jadad AR. Two wrongs don't make a right: harm aggravated by inaccurate information on the Internet. Pediatrics. 2002; 109:522–3.

Article13. Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, Rose C, Leddin D, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007; 102:2070–7.

Article14. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999; 53:105–11.

Article15. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33:159–74.

Article16. Chang MC, Park D. YouTube as a source of information on epidural steroid injection. J Pain Res. 2021; 14:1353–7.

Article17. Stalonas PM, Keane TM, Foy DW. Alcohol education for inpatient alcoholics: a comparison of live, videotape and written presentation modalities. Addict Behav. 1979; 4:223–9.

Article18. Kim JY, Shim JH, Hong SJ, Yang JY, Choi HR, Lim YH, et al. Sufficient explanation of management affects patient satisfaction and the practice of post-treatment management in spinal pain, a multicenter study of 1007 patients. Korean J Pain. 2017; 30:116–25.

Article19. Crocco AG, Villasis-Keever M, Jadad AR. Analysis of cases of harm associated with use of health information on the internet. JAMA. 2002; 287:2869–71.

Article20. Lee KN, Son GH, Park SH, Kim Y, Park ST. YouTube as a source of information and education on hysterectomy. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35:e196.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Radionuclide Therapy Videos on YouTube as An Educational Material: Has the COVID‑19 Pandemic Changed the Quality, Usefulness, and Interaction Features

- Evaluation of the Quality of Educational YouTube Videos on Endoscopic Choanal Atresia

- YouTube videos provide low-quality educational content about rotator cuff disease

- Evaluation of the reliability and information quality of YouTube videos on implant overdenture

- YouTube as a source of information about rubber dam: quality and content analysis