J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Jan;37(1):e3. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e3.

Delayed Influenza Treatment in Children With False-Negative Rapid Antigen Test: A Retrospective Single-Center Study in Korea 2016–2019

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Severance Children’s Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Institute for Immunology and Immunological Disease, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2524181

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e3

Abstract

- Background

We aimed to examine the delay in antiviral initiation in rapid antigen test (RAT) false-negative children with influenza virus infection and to explore the clinical outcomes. We additionally conducted a medical cost-benefit analysis.

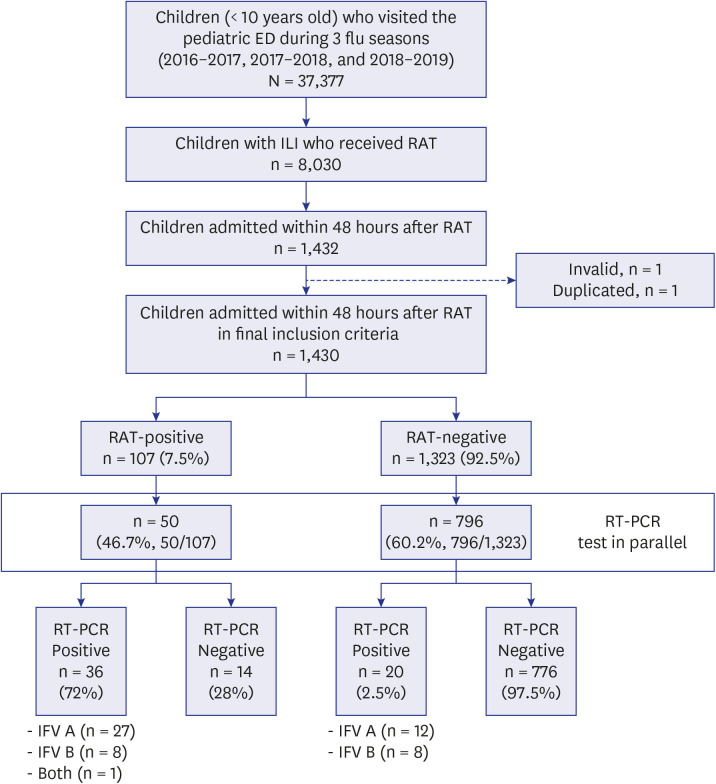

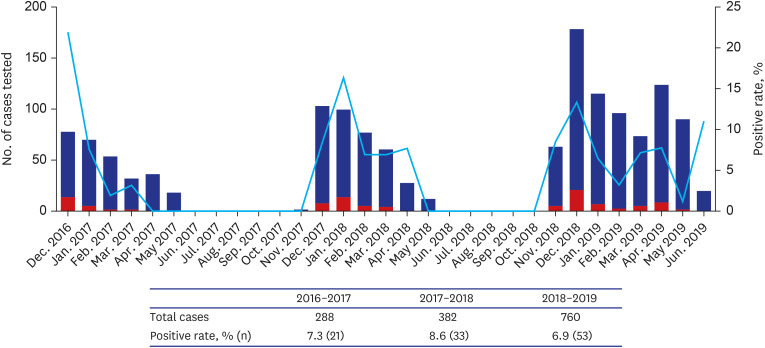

Methods

This single-center, retrospective study included children (aged < 10 years) with influenza-like illness (ILI), hospitalized after presenting to the emergency department during three influenza seasons (2016–2019). RAT-false-negativity was defined as RAT-negative and polymerase chain reaction-positive cases. The turnaround time to antiviral treatment (TAT) was from the time when RAT was prescribed to the time when the antiviral was administered. The medical cost analysis by scenarios was also performed.

Results

A total of 1,430 patients were included, 7.5% were RAT-positive (n = 107) and 2.4% were RAT-false-negative (n = 20). The median TAT of RAT-false-negative patients was 52.8 hours, significantly longer than that of 4 hours in RAT-positive patients (19.2–100.1, P< 0.001). In the multivariable analysis, TAT of ≥ 24 hours was associated with a risk of severe influenza infection and the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio [OR], 6.8, P = 0.009 and OR, 16.2, P = 0.033, respectively). The medical cost varied from $11.7–187.3/ILI patient.

Conclusion

Antiviral initiation was delayed in RAT-false-negative patients. Our findings support the guideline that children with influenza, suspected of having severe or progressive infection, should be treated immediately.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Wang X, Li Y, O’Brien KL, Madhi SA, Widdowson MA, Byass P, et al. Global burden of respiratory infections associated with seasonal influenza in children under 5 years in 2018: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8(4):497–510.2. Castillejos M, Cabello-Gutiérrez C, Alberto Choreño-Parra J, Hernández V, Romo J, Hernández-Sánchez F, et al. High performance of rapid influenza diagnostic test and variable effectiveness of influenza vaccines in Mexico. Int J Infect Dis. 2019; 89:87–95. PMID: 31493523.

Article3. Sohn YJ, Choi JH, Choi YY, Choe YJ, Kim K, Kim YK, et al. Effectiveness of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines in children during 2017-2018 season in Korea: comparison of test-negative analysis by rapid and RT-PCR influenza tests. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 99:199–203. PMID: 32717398.

Article4. Yoon Y, Choi JS, Park M, Cho H, Park M, Huh HJ, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in children at the emergency department during the 2018-2019 season: the first season school-aged children were included in the Korean influenza national immunization program. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(10):e71. PMID: 33724738.

Article5. Falsey AR, Murata Y, Walsh EE. Impact of rapid diagnosis on management of adults hospitalized with influenza. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167(4):354–360. PMID: 17242309.

Article6. Bonner AB, Monroe KW, Talley LI, Klasner AE, Kimberlin DW. Impact of the rapid diagnosis of influenza on physician decision-making and patient management in the pediatric emergency department: results of a randomized, prospective, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2003; 112(2):363–367. PMID: 12897288.

Article7. Clark TW, Beard KR, Brendish NJ, Malachira AK, Mills S, Chan C, et al. Clinical impact of a routine, molecular, point-of-care, test-and-treat strategy for influenza in adults admitted to hospital (FluPOC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 9(4):419–429. PMID: 33285143.

Article8. Basile K, Kok J, Dwyer DE. Point-of-care diagnostics for respiratory viral infections. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2018; 18(1):75–83. PMID: 29251007.

Article9. Chartrand C, Leeflang MM, Minion J, Brewer T, Pai M. Accuracy of rapid influenza diagnostic tests: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 156(7):500–511. PMID: 22371850.10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation of 11 commercially available rapid influenza diagnostic tests--United States, 2011-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012; 61(43):873–876. PMID: 23114254.11. Azar MM, Landry ML. Detection of influenza A and B viruses and respiratory syncytial virus by use of Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)-waived point-of-care assays: a paradigm shift to molecular tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2018; 56(7):e00367-18. PMID: 29695519.

Article12. Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, Englund JA, File TM Jr, Fry AM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 update on diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management of seasonal influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2019; 68(6):e1–47.13. Choi WS. The national influenza surveillance system of Korea. Infect Chemother. 2019; 51(2):98–106. PMID: 31270989.

Article14. Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, Gubareva L, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM, et al. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza --- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011; 60(1):1–24.15. Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, Leonardi-Bee J, Al Khuwaitir TS, Al Mamun A, et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2014; 2(5):395–404. PMID: 24815805.

Article16. Hiba V, Chowers M, Levi-Vinograd I, Rubinovitch B, Leibovici L, Paul M. Benefit of early treatment with oseltamivir in hospitalized patients with documented 2009 influenza A (H1N1): retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011; 66(5):1150–1155. PMID: 21393197.

Article17. Fowlkes AL, Steffens A, Reed C, Temte JL, Campbell AP, Rubino H, et al. Influenza antiviral prescribing practices and the influence of rapid testing among primary care providers in the US, 2009-2016. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019; 6(6):ofz192. PMID: 31205973.

Article18. Avril E, Lacroix S, Vrignaud B, Moreau-Klein A, Coste-Burel M, Launay E, et al. Variability in the diagnostic performance of a bedside rapid diagnostic influenza test over four epidemic seasons in a pediatric emergency department. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016; 85(3):334–337. PMID: 27139081.

Article19. Uyeki TM. Oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 66(10):1501–1503. PMID: 29315362.

Article20. Coffin SE, Leckerman K, Keren R, Hall M, Localio R, Zaoutis TE. Oseltamivir shortens hospital stays of critically ill children hospitalized with seasonal influenza: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011; 30(11):962–966. PMID: 21997661.21. Malosh RE, Martin ET, Heikkinen T, Brooks WA, Whitley RJ, Monto AS. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in children: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 66(10):1492–1500. PMID: 29186364.

Article22. Strong M, Burrows J, Stedman E, Redgrave P. Adverse drug effects following oseltamivir mass treatment and prophylaxis in a school outbreak of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) in June 2009, Sheffield, United Kingdom. Euro Surveill. 2010; 15(19):19565. PMID: 20483106.

Article23. Stephenson I, Democratis J, Lackenby A, McNally T, Smith J, Pareek M, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance after oseltamivir treatment of acute influenza A and B in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 48(4):389–396. PMID: 19133796.

Article24. Diel R, Nienhaus A. Cost-benefit analysis of real-time influenza testing for patients in German emergency rooms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2368.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Analysis of Influenza in Children and Rapid Antigen Detection Test on First Half of the Year 2004 in Busan

- Comparison of Rapid Antigen Test and Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR for the Detection of Influenza B Virus

- Comparison of SD BIOLINE Rapid Influenza Antigen Test Using Two Different Specimens, Nasopharyngeal Swabs and Nasopharyngeal Aspirates

- Detection Rate of Rapid Antigen Test for Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1 2009)

- Usefulness of Influenza Rapid Antigen Test in Influenza A (H1N1)