J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Aug;36(33):e210. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e210.

Surge Capacity and Mass Casualty Incidents Preparedness of Emergency Departments in a Metropolitan City: a Regional Survey Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Laboratory of Emergency Medical Services, Seoul National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Hanyang University Seoul Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Emergency Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Emergency Medicine, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2519351

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e210

Abstract

- Background

Emergency departments (EDs) generally receive many casualties in disaster or mass casualty incidents (MCI). Some studies have conceptually suggested the surge capacity that ED should have; however, only few studies have investigated measurable numbers in one community. This study investigated the surge capacity of the specific number of accommodatable patients and overall preparedness at EDs in a metropolitan city.

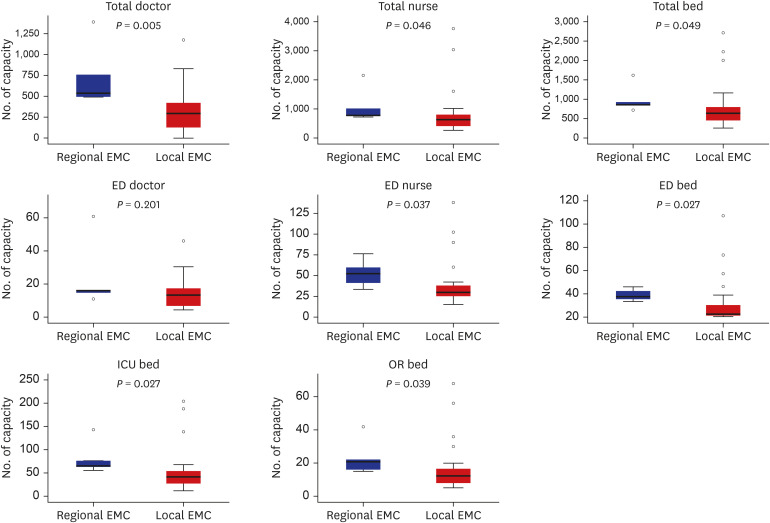

Methods

This cross-sectional study officially surveyed surge capacity and disaster preparedness for all regional and local emergency medical centers (EMC) in Seoul with the Seoul Metropolitan Government's public health division. This study developed survey items on space, staff, stuff, and systems, which are essential elements of surge capacity. The number of patients acceptable for each ED was investigated by triage level in ordinary and crisis situations. Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed on hospital resource variables related to surge capacity.

Results

In the second half of 2018, a survey was conducted targeting 31 EMC directors in Seoul. It was found that all regional and local EMCs in Seoul can accommodate 848 emergency patients and 537 non-emergency patients in crisis conditions. In ordinary situations, one EMC could accommodate an average of 1.3 patients with Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) level 1, 3.1 patients with KTAS level 2, and 5.7 patients with KTAS level 3. In situations of crisis, this number increased to 3.4, 7.8, and 16.2, respectively. There are significant differences in surge capacity between ordinary and crisis conditions. The difference in surge capacity between regional and local EMC was not significant. In both ordinary and crisis conditions, only the total number of hospital beds were significantly associated with surge capacity.

Conclusion

If the hospital's emergency transport system is ideally accomplished, patients arising from average MCI can be accommodated in Seoul. However, in a huge disaster, it may be challenging to handle the current surge capacity. More detailed follow-up studies are needed to prepare a surge capacity protocol in the community.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Smith JE, Gebhart ME. Patient surge. In : Ciottone GR, editor. Ciottone's Disaster Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier;2015. p. 233–240.2. Barbisch DF. Surge capacity and scarce resource allocation. In : Koenig KL, Schultz CH, editors. Koenig and Schultz's Disaster Medicine. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;2016. p. 38–51.3. Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, DeAtley C, Barbisch D, Bogdan GM, et al. Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 44(3):253–261. PMID: 15332068.

Article4. Barbera JA, Macintyre AG, Knebel A, Trabert E. Medical Surge Capacity and Capability: a Management System for Integrating Medical and Health Resources During Large-Scale Emergencies. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services;2007.5. American College of Emergency Physicians. Health care system surge capacity recognition, preparedness, and response. Ann Emerg Med. 2005; 45(2):239. PMID: 15671992.6. Barbisch DF, Koenig KL. Understanding surge capacity: essential elements. Acad Emerg Med. 2006; 13(11):1098–1102. PMID: 17085738.

Article7. Kaji A, Koenig KL, Bey T. Surge capacity for healthcare systems: a conceptual framework. Acad Emerg Med. 2006; 13(11):1157–1159. PMID: 16968688.

Article8. Sheikhbardsiri H, Raeisi AR, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Rezaei F. Surge capacity of hospitals in emergencies and disasters with a preparedness approach: a systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017; 11(5):612–620. PMID: 28264731.

Article9. Hick JL, Einav S, Hanfling D, Kissoon N, Dichter JR, Devereaux AV, et al. Surge capacity principles: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014; 146(4):Suppl. e1S–e16S. PMID: 25144334.10. De Boer J. Order in chaos: modelling medical management in disasters. Eur J Emerg Med. 1999; 6(2):141–148. PMID: 10461559.

Article11. Hirshberg A, Scott BG, Granchi T, Wall MJ Jr, Mattox KL, Stein M. How does casualty load affect trauma care in urban bombing incidents? A quantitative analysis. J Trauma. 2005; 58(4):686–693. PMID: 15824643.

Article12. Rivara FP, Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV. Do trauma centers have the capacity to respond to disasters? J Trauma. 2006; 61(4):949–953. PMID: 17033567.

Article13. Bayram JD, Zuabi S, Subbarao I. Disaster metrics: quantitative benchmarking of hospital surge capacity in trauma-related multiple casualty events. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011; 5(2):117–124. PMID: 21685307.

Article14. Total population of Seoul. Updated 2021. Accessed February 2, 2021. http://english.seoul.go.kr/seoul-views/meaning-of-seoul/4-population/.15. Lee MS, Kang RH, Ham BJ, Choi YK, Han CS, Lee HJ, et al. A study of disaster survivors in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2004; 1(1):68–75.16. Kwon H, Kim YJ, Jo YH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim J, et al. The Korean Triage and Acuity Scale: associations with admission, disposition, mortality and length of stay in the emergency department. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019; 31(6):449–455. PMID: 30165654.

Article17. The Emergency Medical Response Manual for Disasters (Korean). Updated 2016. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb0406vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=030406&CONT_SEQ=329536&page=1.18. Lin YK, Niu KY, Seak CJ, Weng YM, Wang JH, Lai PF. Comparison between simple triage and rapid treatment and Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale for the emergency department triage of victims following an earthquake-related mass casualty incident: a retrospective cohort study. World J Emerg Surg. 2020; 15(1):20. PMID: 32156308.

Article19. Cha MI, Choa M, Kim S, Cho J, Choi DH, Cho M, et al. Changes to the Korean disaster medical assistance system after numerous multi-casualty incidents in 2014 and 2015. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017; 11(5):526–530. PMID: 28659222.

Article20. Cha MI, Kim GW, Kim CH, Choa M, Choi DH, Kim I, et al. A study on the disaster medical response during the Mauna Ocean Resort gymnasium collapse. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2016; 3(3):165–174. PMID: 27752635.

Article21. Terndrup TE, Leaming JM, Adams RJ, Adoff S. Hospital-based coalition to improve regional surge capacity. West J Emerg Med. 2012; 13(5):445–452. PMID: 23316266.

Article22. Schultz CH, Stratton SJ. Improving hospital surge capacity: a new concept for emergency credentialing of volunteers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49(5):602–609. PMID: 17112633.

Article23. TariVerdi M, Miller-Hooks E, Kirsch T. Strategies for improved hospital response to mass casualty incidents. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2018; 12(6):778–790. PMID: 29553040.

Article24. Park JO, Shin SD, Song KJ, Hong KJ, Kim J. Epidemiology of emergency medical services-assessed mass casualty incidents according to causes. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(3):449–456. PMID: 26955248.

Article25. Waxman DA, Chan EW, Pillemer F, Smith TW, Abir M, Nelson C. Assessing and improving hospital mass-casualty preparedness: a no-notice exercise. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017; 32(6):662–666. PMID: 28780916.

Article26. Abir M, Davis MM, Sankar P, Wong AC, Wang SC. Design of a model to predict surge capacity bottlenecks for burn mass casualties at a large academic medical center. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013; 28(1):23–32. PMID: 23174042.

Article27. Jacobs-Wingo JL, Cook HA, Lang WH. Rapid patient discharge contribution to bed surge capacity during a mass casualty incident: findings from an exercise with New York City hospitals. Qual Manag Health Care. 2018; 27(1):24–29. PMID: 29280904.

Article28. Kelen GD, Kraus CK, McCarthy ML, Bass E, Hsu EB, Li G, et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity: a multiphase study. Lancet. 2006; 368(9551):1984–1990. PMID: 17141705.

Article29. Kelen GD, Troncoso R, Trebach J, Levin S, Cole G, Delaney CM, et al. Effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017; 171(4):e164829. PMID: 28152138.

Article30. Kanter RK, Moran JR. Hospital emergency surge capacity: an empiric New York statewide study. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 50(3):314–319. PMID: 17178173.

Article31. DeLia D. Annual bed statistics give a misleading picture of hospital surge capacity. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; 48(4):384–388. 388.e1–388.e2. PMID: 16997673.

Article32. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005 with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD, USA: National Center for Health Statistics;2005.33. Bed occupancy rate 2015, South Korea (Korean). Updated 2019. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?tblId=DT_117049_A050&orgId=117&language=kor&conn_path=&vw_cd=&list_id=.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Characteristics of mass casualty chemical incidents: a case series

- Incidence and Mortality Rates of Disasters and Mass Casualty Incidents in Korea: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study, 2000-2009

- Disaster Basic Physics and Disaster Paradigm

- Hospital Triage System in Mass Casualty Incident

- Victim-oriented digital disaster emergency medical system