Anat Cell Biol.

2021 Jun;54(2):292-296. 10.5115/acb.21.063.

Osteochondrosis dissecans in glenoid cavity of Korean War casualty’s scapula

- Affiliations

-

- 1Ministry of National Defense Agency for KIA Recovery & Identification, Seoul, Korea

- 2Institute of Forensic and Anthropological Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Radiology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Radiology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Research and Development, MEDICALIP Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea

- 6Laboratory of Bioanthropology, Paleopathology and History of Diseases, Department of Anatomy, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2516915

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5115/acb.21.063

Abstract

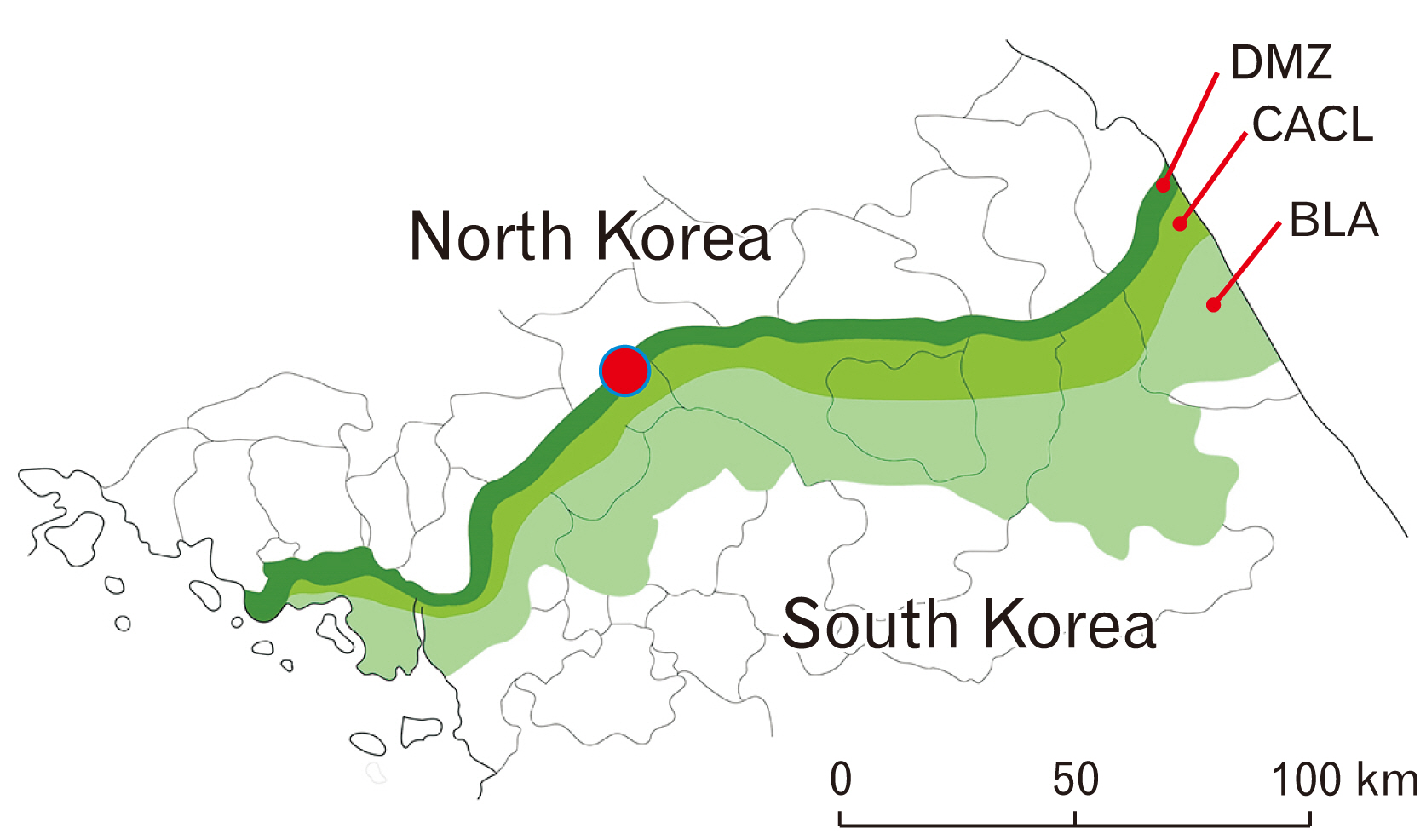

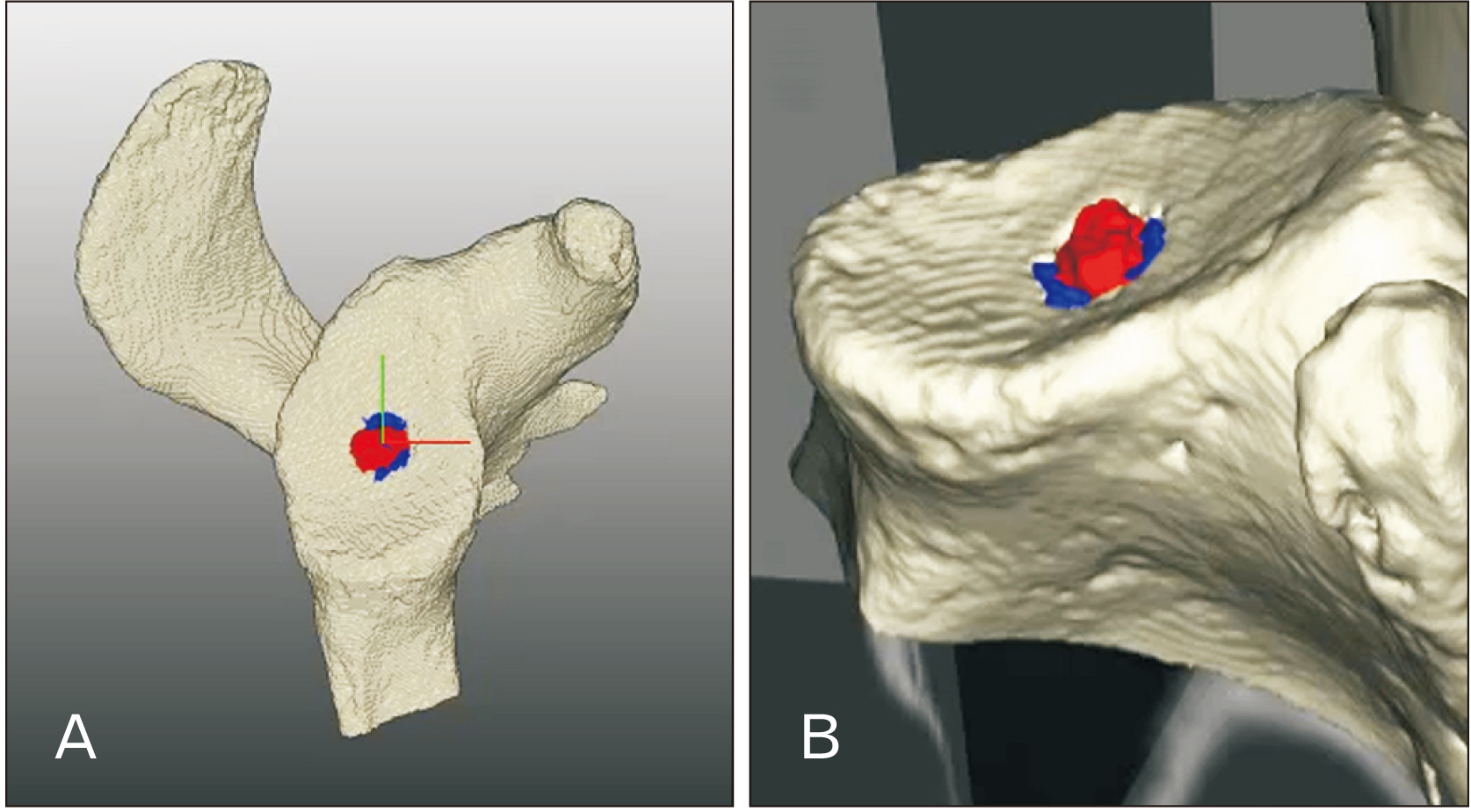

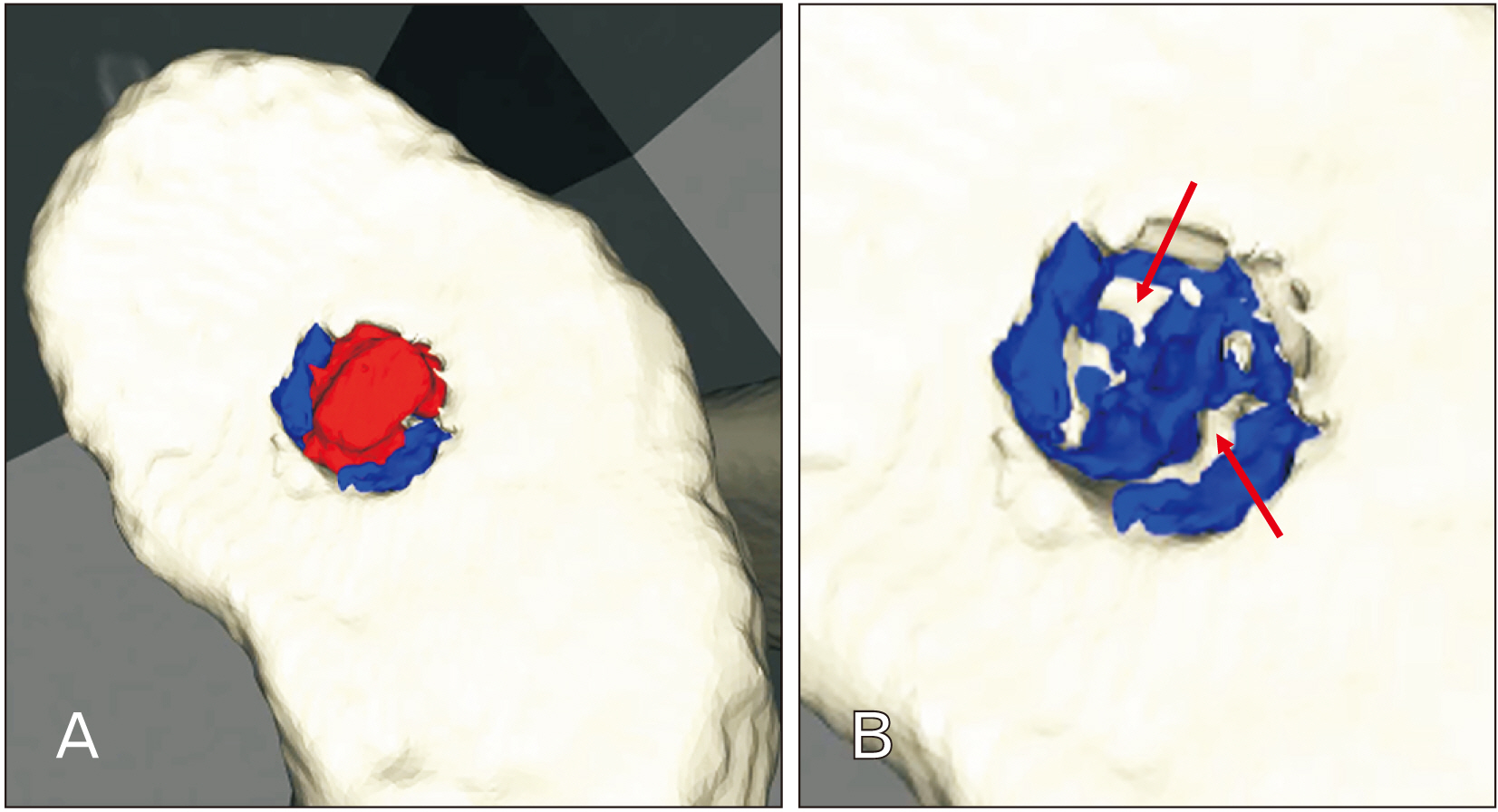

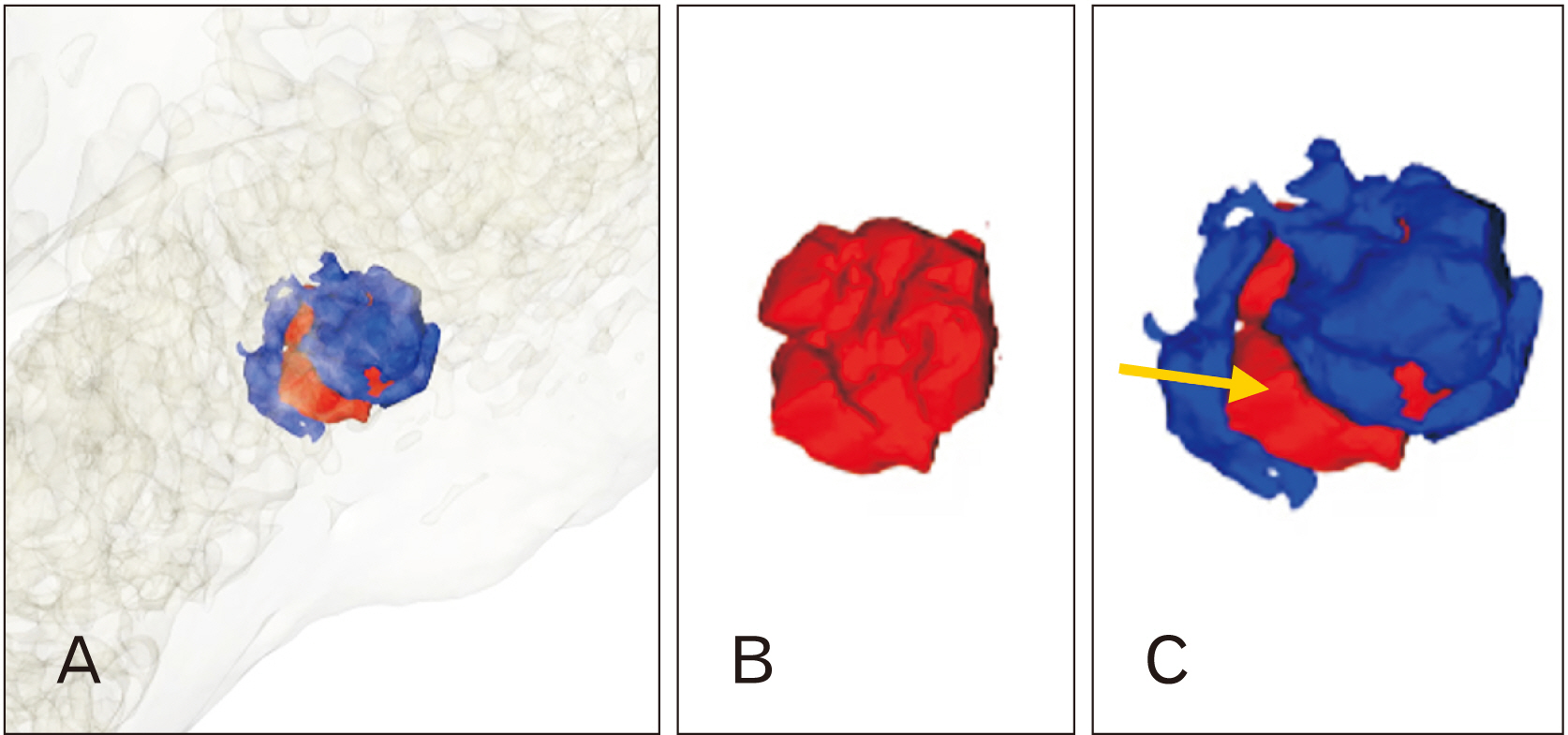

- Since the first description of this disease in 1887, there are rare reports on osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD) found in the glenoid cavity by way of anthropological studies. During an excavation project for recovery of the remains of Korean War casualties, a skeletonized soldier was found inside a cave fort at the Arrowhead Ridge of the demilitarized zone (DMZ), South Korea. In our recovery and examination of a Korean War casualty in DMZ, we identified a possible OCD in the individual’s glenoid cavity of a right-sided scapula by radiological analysis and computed tomography reconstruction. This is a rare case of scapular OCD discovered in an archaeologically investigated skeleton.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Clanton TO, DeLee JC. 1982; Osteochondritis dissecans. History, pathophysiology and current treatment concepts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (167):50–64. DOI: 10.1097/00003086-198207000-00009. PMID: 6807595.

Article2. Edmonds EW, Polousky J. 2013; A review of knowledge in osteochondritis dissecans: 123 years of minimal evolution from König to the ROCK study group. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 471:1118–26. DOI: 10.1007/s11999-012-2290-y. PMID: 22362466. PMCID: PMC3586043.

Article3. Chu PJ, Shih JT, Hou YT, Hung ST, Chen JK, Lee HM. 2009; Osteochondritis dissecans of the glenoid: a rare injury secondary to repetitive microtrauma. J Trauma. 67:E62–4. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318047c02a. PMID: 19741376.

Article4. Zúñiga Thayer R, Suby J, Luna L, Flensborg G. 2021; Osteochondritis dissecans and physical activity in skeletal remains of ancient hunter-gatherers from Southern Patagonia. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 31:77–87. DOI: 10.1002/oa.2926.5. Anderson T. 2000; A medieval Italian child with osteochondritis dissecans of the cuboid. Foot. 10:216–8. DOI: 10.1054/foot.2000.0620.

Article6. Anderson T. 2001; An example of unhealed osteochondritis dissecans of the medial cuneiform. Foot. 11:251–3. DOI: 10.1054/foot.2002.0708.

Article7. Vikatou I, Hoogland MLP, Waters-Rist AL. 2017; Osteochondritis Dissecans of skeletal elements of the foot in a 19th century rural farming community from The Netherlands. Int J Paleopathol. 19:53–63. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2017.09.005. PMID: 29198400.

Article8. Pany-Kucera D, Kern A, Reschreiter H. 2019; Children in the mines? Tracing potential childhood labour in salt mines from the Early Iron Age in Hallstatt, Austria. Child Past. 12:67–80. DOI: 10.1080/17585716.2019.1638554.

Article9. Buikstra JE, Ubelaker DH. 1994. Standards for data collection from human skeletal remains: proceedings of a Seminar at The Field Museum of Natural History. 12154th ed. Arkansas Archeological Survey;Fayetteville:10. Lovejoy CO, Meindl RS, Mensforth RP, Barton TJ. 1985; Multifactorial determination of skeletal age at death: a method and blind tests of its accuracy. Am J Phys Anthropol. 68:1–14. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330680102. PMID: 4061595.

Article11. Trotter M, Gleser GC. 1958; A re-evaluation of estimation of stature based on measurements of stature taken during life and of long bones after death. Am J Phys Anthropol. 16:79–123. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330160106. PMID: 13571400.

Article12. Bradley J, Dandy DJ. 1989; Osteochondritis dissecans and other lesions of the femoral condyles. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 71:518–22. DOI: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B3.2722949. PMID: 2722949.

Article13. Bohndorf K. 1998; Osteochondritis (osteochondrosis) dissecans: a review and new MRI classification. Eur Radiol. 8:103–12. DOI: 10.1007/s003300050348. PMID: 9442140.

Article14. Andriolo L, Crawford DC, Reale D, Zaffagnini S, Candrian C, Cavicchioli A, Filardo G. 2020; Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: etiology and pathogenetic mechanisms. a systematic review. Cartilage. 11:273–90. DOI: 10.1177/1947603518786557. PMID: 29998741. PMCID: PMC7298596.

Article15. Buckley SL, Alexander A, Jones M, Culp RW, Smallman T. 1992; Arthroscopic surgery of the knee: its role in the support of U.S. troops during Operation Desert Shield on USNS mercy. Arthroscopy. 8:359–62. DOI: 10.1016/0749-8063(92)90068-M. PMID: 1418209.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Extension of a Scapular Fracture into the Glenoid Cavity after Low-voltage Electric Shock

- Development of the Shoulder Joint in Staged Human Embryos and Fetuses in Korean

- Morphometric Study on the Coracoacromial Arch, the Acromial Articular Surface, and the Glenoid Cavit of the Scapula in Koreans

- Arthroscopic-assisted Reduction and Percutaneous Screw Fixation for Glenoid Fracture with Scapular Extension

- Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee Associated with Gout: A Case Report