Prenatal ultrasonographic findings of esophageal atresia: potential diagnostic role of the stomach shape

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2511564

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.20207

Abstract

Objective

We investigated prenatal sonographic characteristics of esophageal atresia (EA) with advancing gestation. We focused on the degree of polyhydramnios and the stomach shape.

Methods

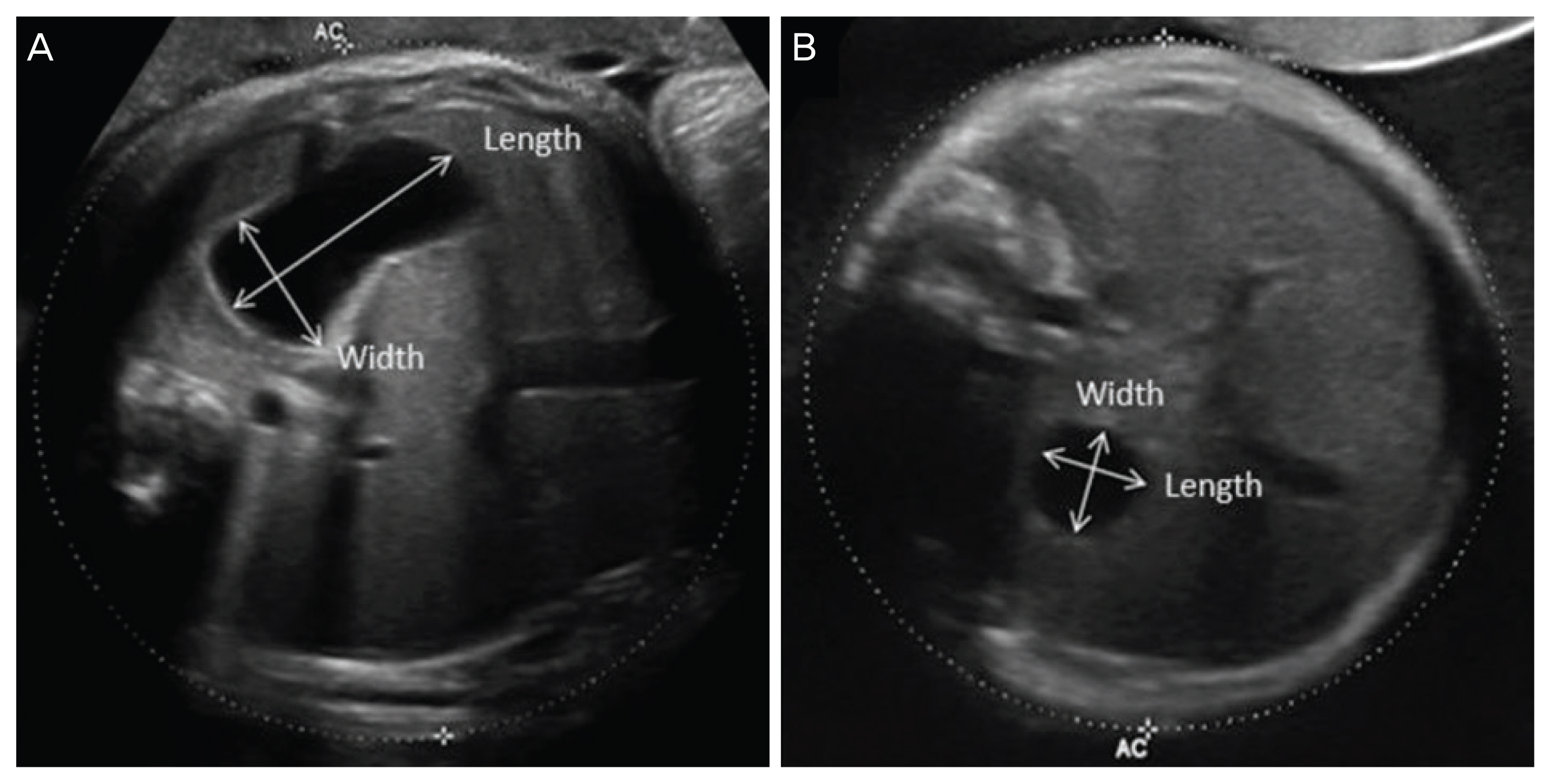

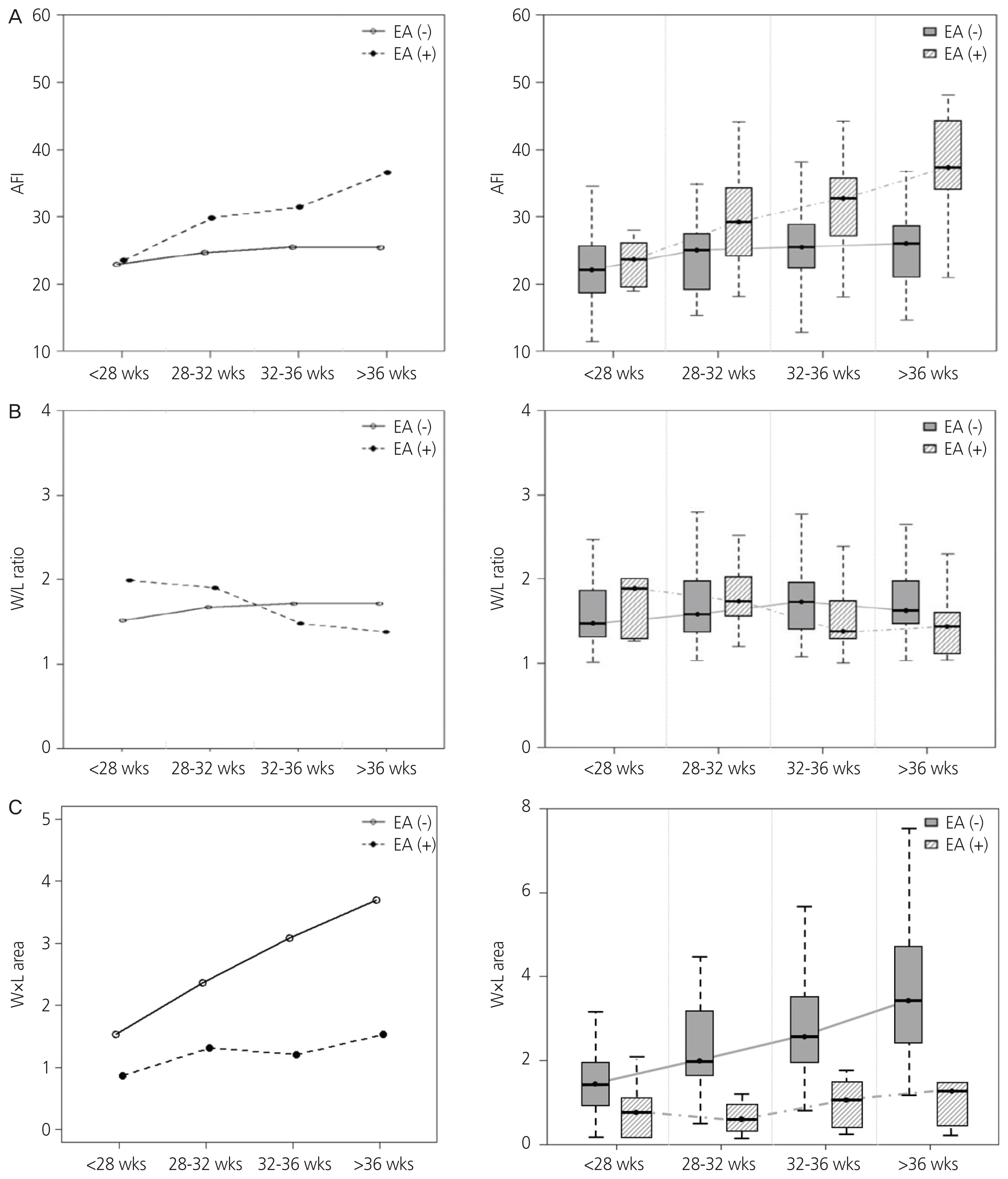

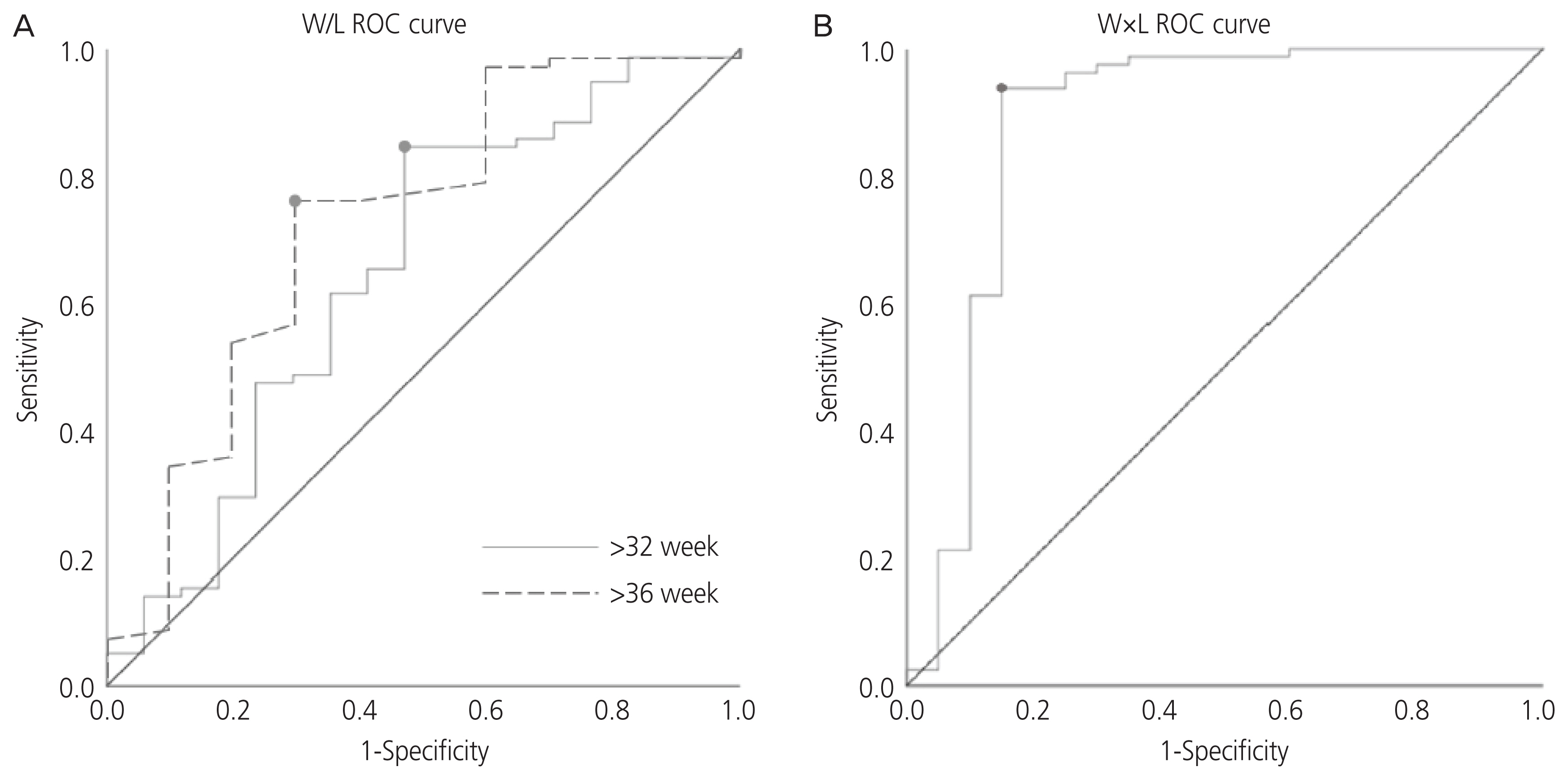

This study included 27 EA cases (EA group) and 81 idiopathic polyhydramnios cases (non-EA group). The non-EA group consisted of cases without any fetal structural anomaly, musculoskeletal disorder, chromosomal abnormality, or maternal diabetes. Both groups included only singleton pregnancies. Amniotic fluid index (AFI) and width/length (W/L) ratio as well as the product of width and length (W×L) of stomach were serially assessed during gestation and compared between the 2 groups. To predict EA using W/L ratio and W×L, receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was performed.

Results

Polyhydramnios was evident in 77.8% of EA cases. We observed 25.9% and 22.2% EA cases with an absent stomach and a small visible stomach, respectively. After 28 weeks, the EA group manifested significantly higher AFI than the non-EA group. After 32 weeks, W/L ratio in the EA group tended to be lower than that in the non-EA group (32–36 weeks: 1.36 vs. 1.72, P=0.092; >36 weeks: 1.43 vs. 1.63, P=0.024). To predict EA, the calculated area under the curve for W/L ratio was 0.651 after 32 weeks. The diagnosis of EA using a cut-off value of W/L ratio <1.376 showed sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio to be 84.6%, 52.9%, 1.796, and 0.081, respectively.

Conclusion

A low W/L ratio of stomach after 32 weeks with progressive idiopathic polyhydramnios may be used to predict EA.

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

The Effect of Vanishing Twin on First- and Second-Trimester Maternal Serum Markers and Nuchal Translucency: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study

Se Jin Lee, You Jung Han, Minhyoung Kim, Jae-Yoon Shim, Mi-Young Lee, Soo-young Oh, JoonHo Lee, Soo Hyun Kim, Dong Hyun Cha, Geum Joon Cho, Han-Sung Kwon, Byoung Jae Kim, Mi Hye Park, Hee Young Cho, Hyun Sun Ko, Ji Hye Bae, Chan-Wook Park, Joong Shin Park, Jong Kwan Jun, Sohee Oh, Da Rae Lee, Hyun Mee Ryu, Seung Mi Lee

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(38):e300. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e300.The effect of a vanishing twin on first- and second-trimester maternal serum markers and ultrasound screening for aneuploidy

Da Rae Lee, SeungMi Lee, Se Jin Lee

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2023;66(6):477-483. doi: 10.5468/ogs.22270.

Reference

-

References

1. Torfs CP, Curry CJ, Bateson TF. Population-based study of tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia. Teratology. 1995; 52:220–32.

Article2. Felix JF, Tibboel D, de Klein A. Chromosomal anomalies in the aetiology of oesophageal atresia and tracheooesophageal fistula. Eur J Med Genet. 2007; 50:163–75.

Article3. Koivusalo AI, Pakarinen MP, Rintala RJ. Modern outcomes of oesophageal atresia: single centre experience over the last twenty years. J Pediatr Surg. 2013; 48:297–303.

Article4. Deurloo JA, Ekkelkamp S, Schoorl M, Heij HA, Aronson DC. Esophageal atresia: historical evolution of management and results in 371 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002; 73:267–72.

Article5. Lopez PJ, Keys C, Pierro A, Drake DP, Kiely EM, Curry JI, et al. Oesophageal atresia: improved outcome in high-risk groups? J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41:331–4.

Article6. Bricker L, Garcia J, Henderson J, Mugford M, Neilson J, Roberts T, et al. Ultrasound screening in pregnancy: a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and women’s views. Health Technol Assess. 2000; 4:i–vi. 1–193.

Article7. Stringer MD, McKenna KM, Goldstein RB, Filly RA, Adzick NS, Harrison MR. Prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1995; 30:1258–63.

Article8. Kalache KD, Wauer R, Mau H, Chaoui R, Bollmann R. Prognostic significance of the pouch sign in fetuses with prenatally diagnosed esophageal atresia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 182:978–81.

Article9. Sparey C, Robson SC. Oesophageal atresia. Prenat Diagn. 2000; 20:251–3.

Article10. Hamza A, Herr D, Solomayer EF, Meyberg-Solomayer G. Polyhydramnios: causes, diagnosis and therapy. Geburt-shilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013; 73:1241–6.

Article11. Smith CV, Plambeck RD, Rayburn WF, Albaugh KJ. Relation of mild idiopathic polyhydramnios to perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 79:387–9.

Article12. Yefet E, Daniel-Spiegel E. Outcomes from poly-hydramnios with normal ultrasound. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151948.

Article13. Sandlin AT, Chauhan SP, Magann EF. Clinical relevance of sonographically estimated amniotic fluid volume: polyhydramnios. J Ultrasound Med. 2013; 32:851–63.

Article14. Faure C, Righini Grunder F. Dysmotility in esophageal atresia: pathophysiology, characterization, and treatment. Front Pediatr. 2017; 5:130.

Article15. Kunisaki SM, Bruch SW, Hirschl RB, Mychaliska GB, Treadwell MC, Coran AG. The diagnosis of fetal esophageal atresia and its implications on perinatal outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014; 30:971–7.

Article16. Shulman A, Mazkereth R, Zalel Y, Kuint J, Lipitz S, Avigad I, et al. Prenatal identification of esophageal atresia: the role of ultrasonography for evaluation of functional anatomy. Prenat Diagn. 2002; 22:669–74.

Article17. Kalache KD, Bamberg C, Proquitté H, Sarioglu N, Lebek H, Esser T. Three-dimensional multi-slice view: new prospects for evaluation of congenital anomalies in the fetus. J Ultrasound Med. 2006; 25:1041–9.18. Ethun CG, Fallon SC, Cassady CI, Mehollin-Ray AR, Olutoye OO, Zamora IJ, et al. Fetal MRI improves diagnostic accuracy in patients referred to a fetal center for suspected esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2014; 49:712–5.

Article19. Muller C, Czerkiewicz I, Guimiot F, Dreux S, Salomon LJ, Khen-Dunlop N, et al. Specific biochemical amniotic fluid pattern of fetal isolated esophageal atresia. Pediatr Res. 2013; 74:601–5.

Article20. Czerkiewicz I, Dreux S, Beckmezian A, Benachi A, Salomon LJ, Schmitz T, et al. Biochemical amniotic fluid pattern for prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia. Pediatr Res. 2011; 70:199–202.

Article21. Pardy C, D’Antonio F, Khalil A, Giuliani S. Prenatal detection of esophageal atresia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019; 98:689–99.

Article22. Spaggiari E, Faure G, Rousseau V, Sonigo P, Millischer-Bellaiche AE, Kermorvant-Duchemin E, et al. Performance of prenatal diagnosis in esophageal atresia. Prenat Diagn. 2015; 35:888–93.

Article23. Bradshaw CJ, Thakkar H, Knutzen L, Marsh R, Pacilli M, Impey L, et al. Accuracy of prenatal detection of tracheoesophageal fistula and oesophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2016; 51:1268–72.

Article24. Garabedian C, Sfeir R, Langlois C, Bonnard A, Khen-Dunlop N, Gelas T, et al. Does prenatal diagnosis modify neonatal treatment and early outcome of children with esophageal atresia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 212:340.e1–7.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Esophageal Atresia Associated with Malrotation and Segemental Dilatation of the Ileum

- Prenatal Ultrasonography of Trisomy 18 with Radial Aplasia: A Case Report

- 2 Cases of Congenital Jejunal Atresia Diagnosed by Prenatal Ultrasonography

- A Case of Congenital Duodenal Atresia Diagnosed by Prenatal Ultrasonography

- A Case of the Esophageal Atresia with Distal Tracheoesophageal Fistula Associated with Duodenal Obstrction