Korean Circ J.

2021 Jan;51(1):15-42. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0436.

Updates in Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiology, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia

- 2Westmead Applied Research Centre, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- KMID: 2509901

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0436

Abstract

- Sudden cardiac death (SCD) due to recurrent ventricular tachycardia is an important clinical sequela in patients with structural heart disease. As a result, ventricular tachycardia (VT) has emerged as a major clinical and public health problem. The mechanism of VT is predominantly mediated by re-entry in the presence of arrhythmogenic substrate (scar), though focal mechanisms are also important. Catheter ablation for VT, when compared to standard medical therapy, has been shown to improve VT-free survival and burden of device therapies. Approaches to VT ablation are dependent on the underlying disease process, broadly classified into idiopathic (no structural heart disease) or structural heart disease (ischemic or non-ischemic heart disease). This update aims to review recent advances made for the treatment of VT ablation, with respect to current clinical trials, peri-procedure risk assessments, pre-procedural cardiac imaging, electro-anatomic mapping and advances in catheter and non-catheter based ablation techniques.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Can Artemisinin Be a Game Changer Even as an Antiarrhythmic Drug?

Jongmin Hwang

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(4):251-253. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0031.

Reference

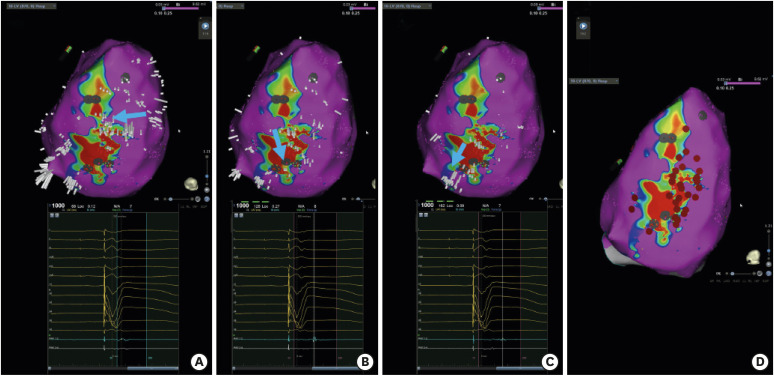

-

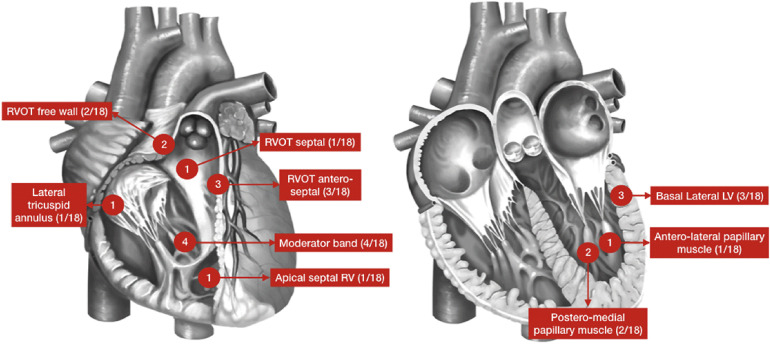

1. Anderson RD, Lee G, Trivic I, et al. Focal ventricular tachycardias in structural heart disease: prevalence, characteristics, and clinical outcomes after catheter ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020; 6:56–69. PMID: 31971907.2. Nakahara S, Tung R, Ramirez RJ, et al. Characterization of the arrhythmogenic substrate in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy implications for catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2355–2365. PMID: 20488307.3. Shirai Y, Liang JJ, Santangeli P, et al. Comparison of the ventricular tachycardia circuit between patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies: detailed characterization by entrainment. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019; 12:e007249. PMID: 31296041.

Article4. Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1009–1017. PMID: 18768944.

Article5. Schron EB, Exner DV, Yao Q, et al. Quality of life in the antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators trial: impact of therapy and influence of adverse symptoms and defibrillator shocks. Circulation. 2002; 105:589–594. PMID: 11827924.6. Strickberger SA, Canby R, Cooper J, et al. Association of antitachycardia pacing or shocks with survival in 69,000 patients with an implantable defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017; 28:416–422. PMID: 28128491.

Article7. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2018; 15:e190–252. PMID: 29097320.8. Bokhari F, Newman D, Greene M, Korley V, Mangat I, Dorian P. Long-term comparison of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus amiodarone: eleven-year follow-up of a subset of patients in the Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study (CIDS). Circulation. 2004; 110:112–116. PMID: 15238454.

Article9. Romero J, Stevenson WG, Fujii A, et al. Impact of number of oral antiarrhythmic drug failures before referral on outcomes following catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 4:810–819. PMID: 29929675.10. Dinov B, Fiedler L, Schönbauer R, et al. Outcomes in catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy compared with ischemic cardiomyopathy: results from the Prospective Heart Centre of Leipzig VT (HELP-VT) Study. Circulation. 2014; 129:728–736. PMID: 24211823.11. Anderson RD, Lee G, Prabhu M, et al. Ten-year trends in catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia vs other interventional procedures in Australia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019; 30:2353–2361. PMID: 31502315.

Article12. Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R, et al. Ventricular tachycardia ablation versus escalation of antiarrhythmic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375:111–121. PMID: 27149033.

Article13. Parkash R, Nault I, Rivard L, et al. Effect of baseline antiarrhythmic drug on outcomes with ablation in ischemic ventricular tachycardia: a VANISH substudy (Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation Versus Escalated Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy in Ischemic Heart Disease). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018; 11:e005663. PMID: 29305400.

Article14. Anderson RD, Ariyarathna N, Lee G, et al. Catheter ablation versus medical therapy for treatment of ventricular tachycardia associated with structural heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and comparison with observational studies. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16:1484–1491. PMID: 31150816.

Article15. Muser D, Santangeli P, Castro SA, et al. Long-term outcome after catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016; 9:9.

Article16. Kumar S, Romero J, Mehta NK, et al. Long-term outcomes after catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with and without structural heart disease. Heart Rhythm. 2016; 13:1957–1963. PMID: 27392945.

Article17. Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, et al. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2006; 113:1807–1816. PMID: 16567565.18. Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Burkhardt DJ, et al. Endo-epicardial homogenization of the scar versus limited substrate ablation for the treatment of electrical storms in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:132–141. PMID: 22766340.

Article19. Anderson RD, Lee G, Campbell T, et al. Scar nonexcitability using simultaneous pacing for substrate ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

Article20. Gökoğlan Y, Mohanty S, Gianni C, et al. Scar homogenization versus limited-substrate ablation in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68:1990–1998. PMID: 27788854.21. Bennett RG, Haqqani HM, Berruezo A, et al. Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in 2018-2019: ARVC/ALVC or both? Heart Lung Circ. 2019; 28:164–177. PMID: 30446243.

Article22. Mahida S, Venlet J, Saguner AM, et al. Ablation compared with drug therapy for recurrent ventricular tachycardia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: results from a multicenter study. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16:536–543. PMID: 30366162.

Article23. Garcia FC, Bazan V, Zado ES, Ren JF, Marchlinski FE. Epicardial substrate and outcome with epicardial ablation of ventricular tachycardia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Circulation. 2009; 120:366–375. PMID: 19620503.

Article24. Romero J, Patel K, Briceno D, et al. Endo-epicardial ablation vs endocardial ablation for the management of ventricular tachycardia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31:2022–2031. PMID: 32478430.

Article25. Kumar S, Barbhaiya C, Nagashima K, et al. Ventricular tachycardia in cardiac sarcoidosis: characterization of ventricular substrate and outcomes of catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:87–93. PMID: 25527825.26. Papageorgiou N, Providência R, Bronis K, et al. Catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review. Europace. 2018; 20:682–691. PMID: 28444174.

Article27. Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Chandanamattha P, et al. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation episodes in Brugada syndrome by catheter ablation over the anterior right ventricular outflow tract epicardium. Circulation. 2011; 123:1270–1279. PMID: 21403098.

Article28. Nademanee K, Haissaguerre M, Hocini M, et al. Mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation associated with early repolarization syndrome. Circulation. 2019; 140:1477–1490. PMID: 31542949.

Article29. Pappone C, Brugada J, Vicedomini G, et al. Electrical substrate elimination in 135 consecutive patients with Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017; 10:e005053. PMID: 28500178.

Article30. Haïssaguerre M, Shoda M, Jaïs P, et al. Mapping and ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2002; 106:962–967. PMID: 12186801.

Article31. Knecht S, Sacher F, Wright M, et al. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation ablation: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:522–528. PMID: 19643313.32. Nogami A. Mapping and ablating ventricular premature contractions that trigger ventricular fibrillation: trigger elimination and substrate modification. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015; 26:110–115. PMID: 25216244.

Article33. Haïssaguerre M, Extramiana F, Hocini M, et al. Mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation associated with long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circulation. 2003; 108:925–928. PMID: 12925452.

Article34. Haïssaguerre M, Duchateau J, Dubois R, et al. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation: role of Purkinje system and microstructural myocardial abnormalities. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020; 6:591–608. PMID: 32553208.35. Nash MP, Mourad A, Clayton RH, et al. Evidence for multiple mechanisms in human ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2006; 114:536–542. PMID: 16880326.

Article36. Nair K, Umapathy K, Farid T, et al. Intramural activation during early human ventricular fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011; 4:692–703. PMID: 21750274.

Article37. Nakamura T, Schaeffer B, Tanigawa S, et al. Catheter ablation of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation in patients with and without structural heart disease. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16:1021–1027. PMID: 30710740.

Article38. Santangeli P, Frankel DS, Tung R, et al. Early mortality after catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:2105–2115. PMID: 28449770.

Article39. Vergara P, Tzou WS, Tung R, et al. Predictive score for identifying survival and recurrence risk profiles in patients undergoing ventricular tachycardia ablation: the I-VT score. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018; 11:e006730. PMID: 30562104.

Article40. Muser D, Castro SA, Liang JJ, Santangeli P. Identifying risk and management of acute haemodynamic decompensation during catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018; 7:282–287. PMID: 30588317.

Article41. Dickfeld T, Calkins H, Zviman M, et al. Anatomic stereotactic catheter ablation on three-dimensional magnetic resonance images in real time. Circulation. 2003; 108:2407–2413. PMID: 14568905.

Article42. Solomon SB, Dickfeld T, Calkins H. Real-time cardiac catheter navigation on three-dimensional CT images. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2003; 8:27–36. PMID: 12652174.43. Berruezo A, Fernández-Armenta J, Andreu D, et al. Scar dechanneling: new method for scar-related left ventricular tachycardia substrate ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:326–336. PMID: 25583983.44. Berruezo A, Fernández-Armenta J, Mont L, et al. Combined endocardial and epicardial catheter ablation in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia incorporating scar dechanneling technique. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012; 5:111–121. PMID: 22205683.

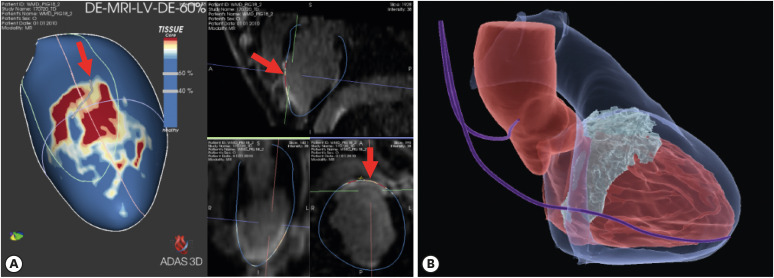

Article45. Ustunkaya T, Desjardins B, Liu B, et al. Association of regional myocardial conduction velocity with the distribution of hypoattenuation on contrast-enhanced perfusion computed tomography in patients with postinfarct ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16:588–594. PMID: 30935494.

Article46. Ustunkaya T, Desjardins B, Wedan R, et al. Epicardial conduction speed, electrogram abnormality, and computed tomography attenuation associations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019; 5:1158–1167. PMID: 31648740.47. Mahida S, Sacher F, Dubois R, et al. Cardiac imaging in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2017; 136:2491–2507. PMID: 29255125.

Article48. Piers SR, Tao Q, van Huls van Taxis CF, Schalij MJ, van der Geest RJ, Zeppenfeld K. Contrast-enhanced MRI-derived scar patterns and associated ventricular tachycardias in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: implications for the ablation strategy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013; 6:875–883. PMID: 24036134.49. Yamashita S, Sacher F, Hooks DA, et al. Myocardial wall thinning predicts transmural substrate in patients with scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2017; 14:155–163. PMID: 28104088.

Article50. Yamashita S, Sacher F, Mahida S, et al. Image integration to guide catheter ablation in scar-related ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016; 27:699–708. PMID: 26918883.

Article51. Andreu D, Ortiz-Pérez JT, Fernández-Armenta J, et al. 3D delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance sequences improve conducting channel delineation prior to ventricular tachycardia ablation. Europace. 2015; 17:938–945. PMID: 25616406.

Article52. Andreu D, Penela D, Acosta J, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance-aided scar dechanneling: influence on acute and long-term outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2017; 14:1121–1128. PMID: 28760258.

Article53. Roca-Luque I, Van Breukelen A, Alarcon F, et al. Ventricular scar channel entrances identified by new wideband cardiac magnetic resonance sequence to guide ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with cardiac defibrillators. Europace. 2020; 22:598–606. PMID: 32101605.

Article54. Penela D, Martínez M, Fernández-Armenta J, et al. Influence of myocardial scar on the response to frequent premature ventricular complex ablation. Heart. 2019; 105:378–383. PMID: 30242139.

Article55. Cury RC, Nieman K, Shapiro MD, et al. Comprehensive assessment of myocardial perfusion defects, regional wall motion, and left ventricular function by using 64-section multidetector CT. Radiology. 2008; 248:466–475. PMID: 18641250.

Article56. Esposito A, Palmisano A, Antunes S, et al. Cardiac CT with delayed enhancement in the characterization of ventricular tachycardia structural substrate: relationship between CT-segmented scar and electro-anatomic mapping. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 9:822–832. PMID: 26897692.57. Deno DC, Balachandran R, Morgan D, Ahmad F, Masse S, Nanthakumar K. Orientation-independent catheter-based characterization of myocardial activation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2017; 64:1067–1077. PMID: 27411215.

Article58. Massé S, Magtibay K, Jackson N, et al. Resolving myocardial activation with novel omnipolar electrograms. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016; 9:e004107. PMID: 27406608.

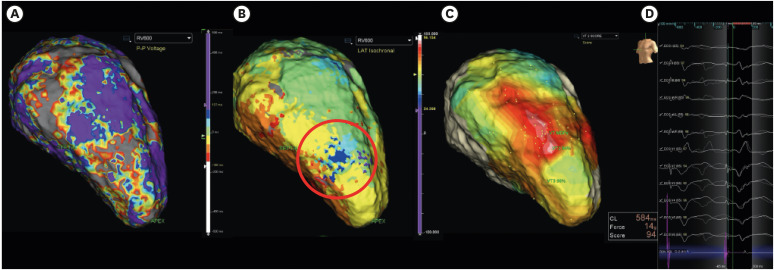

Article59. Magtibay K, Massé S, Asta J, et al. Physiological assessment of ventricular myocardial voltage using omnipolar electrograms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017; 6:e006447. PMID: 28862942.

Article60. Haldar SK, Magtibay K, Porta-Sanchez A, et al. Resolving bipolar electrogram voltages during atrial fibrillation using omnipolar mapping. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017; 10:e005018. PMID: 28887362.

Article61. Porta-Sánchez A, Magtibay K, Nayyar S, et al. Omnipolarity applied to equi-spaced electrode array for ventricular tachycardia substrate mapping. Europace. 2019; 21:813–821. PMID: 30726937.

Article62. Irie T, Yu R, Bradfield JS, et al. Relationship between sinus rhythm late activation zones and critical sites for scar-related ventricular tachycardia: systematic analysis of isochronal late activation mapping. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:390–399. PMID: 25740836.63. Aziz Z, Shatz D, Raiman M, et al. Targeted ablation of ventricular tachycardia guided by wavefront discontinuities during sinus rhythm: a new functional substrate mapping strategy. Circulation. 2019; 140:1383–1397. PMID: 31533463.64. Linton NW, Koa-Wing M, Francis DP, et al. Cardiac ripple mapping: a novel three-dimensional visualization method for use with electroanatomic mapping of cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:1754–1762. PMID: 19959125.

Article65. Jamil-Copley S, Vergara P, Carbucicchio C, et al. Application of ripple mapping to visualize slow conduction channels within the infarct-related left ventricular scar. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:76–86. PMID: 25527678.

Article66. Luther V, Linton NW, Jamil-Copley S, et al. A Prospective study of ripple mapping the post-infarct ventricular scar to guide substrate ablation for ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016; 9:e004072. PMID: 27307519.

Article67. Jackson N, Gizurarson S, Viswanathan K, et al. Decrement evoked potential mapping: basis of a mechanistic strategy for ventricular tachycardia ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:1433–1442. PMID: 26480929.68. Porta-Sánchez A, Jackson N, Lukac P, et al. Multicenter study of ischemic ventricular tachycardia ablation with decrement-evoked potential (DEEP) mapping with extra stimulus. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 4:307–315. PMID: 30089555.69. Rudy Y, Lindsay BD. Electrocardiographic imaging of heart rhythm disorders: from bench to bedside. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2015; 7:17–35. PMID: 25722753.70. Cuculich PS, Zhang J, Wang Y, et al. The electrophysiological cardiac ventricular substrate in patients after myocardial infarction: noninvasive characterization with electrocardiographic imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:1893–1902. PMID: 22018301.71. Zhang J, Sacher F, Hoffmayer K, et al. Cardiac electrophysiological substrate underlying the ECG phenotype and electrogram abnormalities in Brugada syndrome patients. Circulation. 2015; 131:1950–1959. PMID: 25810336.

Article72. Rudic B, Chaykovskaya M, Tsyganov A, et al. Simultaneous non-invasive epicardial and endocardial mapping in patients with Brugada syndrome: new insights into arrhythmia mechanisms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e004095. PMID: 27930354.

Article73. Leong KM, Ng FS, Roney C, et al. Repolarization abnormalities unmasked with exercise in sudden cardiac death survivors with structurally normal hearts. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2018; 29:115–126. PMID: 29091329.

Article74. Graham AJ, Orini M, Zacur E, et al. Evaluation of ECG imaging to map hemodynamically stable and unstable ventricular arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020; 13:e007377. PMID: 31934784.

Article75. Sapp JL, Zhou S, Wang L. Mapping ventricular tachycardia with electrocardiographic imaging. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020; 13:e008255. PMID: 32069088.

Article76. Cronin EM, Bogun FM, Maury P, et al. 2019 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Europace. 2019; 21:1143–1144. PMID: 31075787.77. Campbell T, Trivic I, Bennett RG, et al. Catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmia guided by a high-density grid catheter. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31:474–484. PMID: 31930658.

Article78. Okubo K, Frontera A, Bisceglia C, et al. Grid Mapping Catheter for Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019; 12:e007500. PMID: 31500436.

Article79. St. Jude Medical, Inc. Instructions for Use: Ensite Precision™ Cardiac Mapping System Model EE3000. Software Version 2.0. Saint Paul (MN): St. Jude Medical, Inc.;2016.80. Takigawa M, Relan J, Martin R, et al. Detailed analysis of the relation between bipolar electrode spacing and far- and near-field electrograms. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019; 5:66–77. PMID: 30678788.81. Barkagan M, Sroubek J, Shapira-Daniels A, et al. A novel multielectrode catheter for high-density ventricular mapping: electrogram characterization and utility for scar mapping. Europace. 2020; 22:440–449. PMID: 31985784.

Article82. Sroubek J, Rottmann M, Barkagan M, et al. A novel octaray multielectrode catheter for high-resolution atrial mapping: electrogram characterization and utility for mapping ablation gaps. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019; 30:749–757. PMID: 30723994.

Article83. Viswanathan K, Mantziari L, Butcher C, et al. Evaluation of a novel high-resolution mapping system for catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2017; 14:176–183. PMID: 27867071.

Article84. Liu M, Jiang J, Su C, et al. Electrophysiological characteristics of the earliest activation site in idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract arrhythmias under mini-electrode mapping. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019; 30:642–650. PMID: 30680820.

Article85. Price A, Leshen Z, Hansen J, et al. Novel ablation catheter technology that improves mapping resolution and monitoring of lesion maturation. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2012; 3:599–609.

Article86. Münkler P, Gunawardene MA, Jungen C, et al. Local impedance guides catheter ablation in patients with ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31:61–69. PMID: 31701589.

Article87. Leshem E, Tschabrunn CM, Jang J, et al. High-resolution mapping of ventricular scar: evaluation of a novel integrated multielectrode mapping and ablation catheter. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017; 3:220–231. PMID: 29759516.88. Glashan CA, Tofig BJ, Tao Q, et al. Multisize electrodes for substrate identification in ischemic cardiomyopathy: validation by integration of whole heart histology. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019; 5:1130–1140. PMID: 31648737.89. Tilz RR, Makimoto H, Lin T, et al. In vivo left-ventricular contact force analysis: comparison of antegrade transseptal with retrograde transaortic mapping strategies and correlation of impedance and electrical amplitude with contact force. Europace. 2014; 16:1387–1395. PMID: 24493339.

Article90. Elsokkari I, Sapp JL, Doucette S, et al. Role of contact force in ischemic scar-related ventricular tachycardia ablation; optimal force required and impact of left ventricular access route. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018; 53:323–331. PMID: 29946899.

Article91. Jesel L, Sacher F, Komatsu Y, et al. Characterization of contact force during endocardial and epicardial ventricular mapping. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014; 7:1168–1173. PMID: 25258362.

Article92. Mizuno H, Vergara P, Maccabelli G, et al. Contact force monitoring for cardiac mapping in patients with ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013; 24:519–524. PMID: 23373693.

Article93. Aras D, Özcan F, Çay S, Özeke Ö, Kara M, Topaloğlu S. Endo/epicardial ablation of ventricular arrhythmias with contact force-sensing catheters in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Anatol J Cardiol. 2019; 21:187–195. PMID: 30930451.94. Hendriks AA, Akca F, Dabiri Abkenari L, et al. Safety and clinical outcome of catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias using contact force sensing: consecutive case series. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015; 26:1224–1229. PMID: 26200478.

Article95. Elbatran AI, Li A, Gallagher MM, et al. Contact force sensing in ablation of ventricular arrhythmias using a 56-hole open-irrigation catheter: a propensity-matched analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

Article96. de Vries LJ, Hendriks AA, Yap SC, Theuns DAMJ, van Domburg RT, Szili-Torok T. Procedural and long-term outcome after catheter ablation of idiopathic outflow tract ventricular arrhythmias: comparing manual, contact force, and magnetic navigated ablation. Europace. 2018; 20:ii22–7. PMID: 29722857.

Article97. Sandhu A, Nguyen DT. Forging ahead: update on radiofrequency ablation technology and techniques. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31:360–369. PMID: 31828880.

Article98. Nguyen DT, Gerstenfeld EP, Tzou WS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation using an open irrigated electrode cooled with half-normal saline. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017; 3:1103–1110. PMID: 29759492.99. Nguyen DT, Olson M, Zheng L, Barham W, Moss JD, Sauer WH. Effect of irrigant characteristics on lesion formation after radiofrequency energy delivery using ablation catheters with actively cooled tips. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015; 26:792–798. PMID: 25864402.

Article100. Nguyen DT, Tzou WS, Sandhu A, et al. Prospective multicenter experience with cooled radiofrequency ablation using high impedance irrigant to target deep myocardial substrate refractory to standard ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 4:1176–1185. PMID: 30236391.

Article101. Chung FP, Vicera JJ, Lin YJ, et al. Clinical efficacy of open-irrigated electrode cooled with half-normal saline for initially failed radiofrequency ablation of idiopathic outflow tract ventricular arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019; 30:1508–1516. PMID: 31257650.

Article102. Sapp JL, Cooper JM, Soejima K, et al. Deep myocardial ablation lesions can be created with a retractable needle-tipped catheter. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004; 27:594–599. PMID: 15125714.

Article103. Sapp JL, Beeckler C, Pike R, et al. Initial human feasibility of infusion needle catheter ablation for refractory ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2013; 128:2289–2295. PMID: 24036605.

Article104. Stevenson WG, Tedrow UB, Reddy V, et al. Infusion needle radiofrequency ablation for treatment of refractory ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:1413–1425. PMID: 30922472.105. Della Bella P, Peretto G, Paglino G, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation for ventricular tachycardias originating from the interventricular septum: safety and efficacy in a pilot cohort study. Heart Rhythm. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

Article106. Igarashi M, Nogami A, Fukamizu S, et al. Acute and long-term results of bipolar radiofrequency catheter ablation of refractory ventricular arrhythmias of deep intramural origin. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17:1500–1507. PMID: 32353585.

Article107. Futyma P, Santangeli P, Pürerfellner H, et al. Anatomic approach with bipolar ablation between the left pulmonic cusp and left ventricular outflow tract for left ventricular summit arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17:1519–1527. PMID: 32348845.

Article108. Chang RJ, Stevenson WG, Saxon LA, Parker J. Increasing catheter ablation lesion size by simultaneous application of radiofrequency current to two adjacent sites. Am Heart J. 1993; 125:1276–1284. PMID: 8480578.

Article109. Yang J, Liang J, Shirai Y, et al. Outcomes of simultaneous unipolar radiofrequency catheter ablation for intramural septal ventricular tachycardia in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16:863–870. PMID: 30576879.

Article110. Yamada T, Maddox WR, McElderry HT, Doppalapudi H, Plumb VJ, Kay GN. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from intramural foci in the left ventricular outflow tract: efficacy of sequential versus simultaneous unipolar catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:344–352. PMID: 25637597.111. van der Ree MH, Blanck O, Limpens J, et al. Cardiac radioablation - a systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17:1381–1392. PMID: 32205299.112. Cuculich PS, Schill MR, Kashani R, et al. Noninvasive cardiac radiation for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:2325–2336. PMID: 29236642.

Article113. Neuwirth R, Cvek J, Knybel L, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Europace. 2019; 21:1088–1095. PMID: 31121018.

Article114. Loo BW Jr, Soltys SG, Wang L, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the treatment of refractory cardiac ventricular arrhythmia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015; 8:748–750. PMID: 26082532.

Article115. Robinson CG, Samson PP, Moore KM, et al. Phase I/II trial of electrophysiology-guided noninvasive cardiac radioablation for ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2019; 139:313–321. PMID: 30586734.116. Bhandari AK, Scheinman MM, Morady F, Svinarich J, Mason J, Winkle R. Efficacy of left cardiac sympathectomy in the treatment of patients with the long QT syndrome. Circulation. 1984; 70:1018–1023. PMID: 6499140.

Article117. Wilde AA, Bhuiyan ZA, Crotti L, et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:2024–2029. PMID: 18463378.

Article118. Murtaza G, Sharma SP, Akella K, et al. Role of cardiac sympathetic denervation in ventricular tachycardia: a meta-analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020; 43:828–837. PMID: 32460366.

Article119. Vaseghi M, Barwad P, Malavassi Corrales FJ, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:3070–3080. PMID: 28641796.

Article120. Vaseghi M, Gima J, Kanaan C, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias or electrical storm: intermediate and long-term follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2014; 11:360–366. PMID: 24291775.

Article121. Meng L, Tseng CH, Shivkumar K, Ajijola O. Efficacy of stellate ganglion blockade in managing electrical storm: a systematic review. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017; 3:942–949. PMID: 29270467.122. Hawson J, Harmer JA, Cowan M, et al. Renal denervation for the management of refractory ventricular arrhythmias: a systematic review. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].123. Campbell T, Bennett RG, Garikapati K, et al. Prognostic significance of extensive versus limited induction protocol during catheter ablation of scar-related ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31:2909–2919. PMID: 32905634.

Article124. Soejima K, Stevenson WG, Maisel WH, Sapp JL, Epstein LM. Electrically unexcitable scar mapping based on pacing threshold for identification of the reentry circuit isthmus: feasibility for guiding ventricular tachycardia ablation. Circulation. 2002; 106:1678–1683. PMID: 12270862.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Intramural Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia in a Patient with Severe Hypertensive Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

- Successful Treatment of Tachycardia-induced Cardiomyopathy with Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation

- Successful Catheter Ablation of Focal Automatic Left Ventricular Tachycardia Presented with Tachycardia-Mediated Cardiomyopathy

- Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients without Structural Heart Disease

- Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia/Fibrillation in a Patient with Right Ventricular Amyloidosis with Initial Manifestations Mimicking Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy