J Educ Eval Health Prof.

2020;17:11. 10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.11.

Use of graded responsibility and common entrustment considerations among United States emergency medicine residency programs

- Affiliations

-

- 1BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA

- KMID: 2502197

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.11

Abstract

- Purpose

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires all residency programs to provide increasing autonomy as residents progress through training, known as graded responsibility. However, there is little guidance on how to implement graded responsibility in practice and a paucity of literature on how it is currently implemented in emergency medicine (EM). We sought to determine how EM residency programs apply graded responsibility across a variety of activities and to identify which considerations are important in affording additional responsibilities to trainees.

Methods

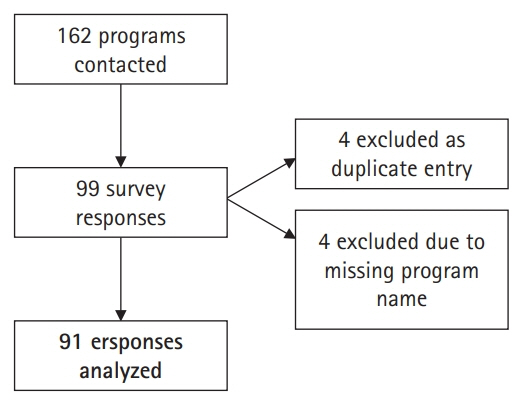

We conducted a cross-sectional study of EM residency programs using a 23-question survey that was distributed by email to 162 ACGME-accredited EM program directors. Seven different domains of practice were queried.

Results

We received 91 responses (56.2% response rate) to the survey. Among all domains of practice except for managing critically ill medical patients, the use of graded responsibility exceeded 50% of surveyed programs. When graded responsibility was applied, post-graduate year (PGY) level was ranked an “extremely important” or “very important” consideration between 80.9% and 100.0% of the time.

Conclusion

The majority of EM residency programs are implementing graded responsibility within most domains of practice. When decisions are made surrounding graded responsibility, programs still rely heavily on the time-based model of PGY level to determine advancement.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements [Internet]. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education;2017. [cited 2019 Dec 19] Available from: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf.2. Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005; 39:1176–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x.

Article3. Franzone JM, Kennedy BC, Merritt H, Casey JT, Austin MC, Daskivich TJ. Progressive independence in clinical training: perspectives of a national, multispecialty panel of residents and fellows. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7:700–704. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-07-04-51.

Article4. Schnapp B, Kraut A, Barclay-Buchannan C, Westergaard M. A graduated responsibility supervising resident experience using mastery learning principles. MedEdPublish. 2019; 8:54. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000203.1.

Article5. Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015: physician competency framework. Ottawa (ON): Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada;2015.6. Beeson MS, Warrington S, Bradford-Saffles A, Hart D. Entrustable professional activities: making sense of the emergency medicine milestones. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47:441–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.06.014.

Article7. Chapple M, Murphy R. The nominal group technique: extending the evaluation of students’ teaching and learning experiences. Assess Eval High Educ. 1996; 21:147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293960210204.

Article8. Schultz K, Griffiths J, Lacasse M. The application of entrustable professional activities to inform competency decisions in a family medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2015; 90:888–897. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000671.

Article9. Norcini J, Burch V. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE guide no. 31. Med Teach. 2007; 29:855–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701775453.

Article10. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, Harris P, Glasgow NJ, Campbell C, Dath D, Harden RM, Iobst W, Long DM, Mungroo R, Richardson DL, Sherbino J, Silver I, Taber S, Talbot M, Harris KA. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010; 32:638–645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190.

Article11. Carraccio C, Englander R, Holmboe ES, Kogan JR. Driving care quality: aligning trainee assessment and supervision through practical application of entrustable professional activities, competencies, and milestones. Acad Med. 2016; 91:199–203. https://do.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000985.12. Li J, Tabor R, Martinez M. Survey of moonlighting practices and work requirements of emergency medicine residents. Am J Emerg Med. 2000; 18:147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-6757(00)90006-8.

Article13. Furnham A. Response bias, social desirability and dissimulation. Pers Individ Dif. 1986; 7:385–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(86)90014-0.

Article14. Berk RA. An introduction to sample selection bias in sociological data. Am Sociol Rev. 1983; 48:386–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095230.

Article15. Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S. The milestones guidebook [Internet]. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education;2016. [cited 2019 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Education regarding opioid prescription within oral and maxillofacial surgery residency programs: a survey study

- Ophthalmology training and competency levels in caring for patients with ophthalmic complaints among United States internal medicine, emergency medicine, and family medicine residents

- Text messaging versus email for emergency medicine residents’ knowledge retention: a pilot comparison in the United States

- Premenarchal ovarian torsion

- Overseas Residency Training Systems and Implications for Korea