Healthc Inform Res.

2020 Jan;26(1):34-41. 10.4258/hir.2020.26.1.34.

Big Data-Driven Approach for Health Inequalities in Foreign Patients with Injuries Visiting Emergency Rooms

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. d2seo@ucsd.edu

- 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Asan Medical Institute of Convergence Science and Technology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4National Emergency Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Convergence Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 6UCSD Health Department of Biomedical Informatics, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

- KMID: 2469398

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2020.26.1.34

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Foreign patients are more likely to receive inappropriate health service in the emergency room. This study aimed to investigate whether there is health inequality between foreigners and natives who visited emergency rooms with injuries and to examine its causes.

METHODS

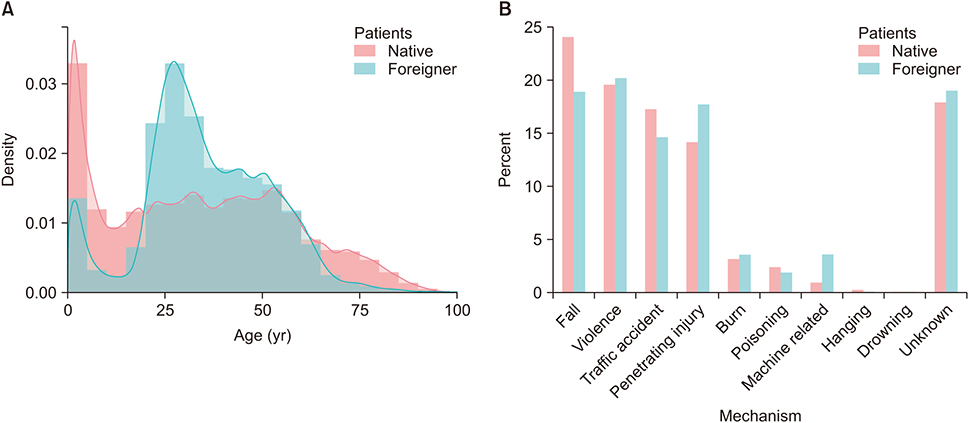

We analyzed clinical data from the National Emergency Department Information System database associated with patients of all age groups visiting the emergency room from 2013 to 2015. We analyzed data regarding mortality, intensive care unit admission, emergency operation, severity, area, and transfer ratio.

RESULTS

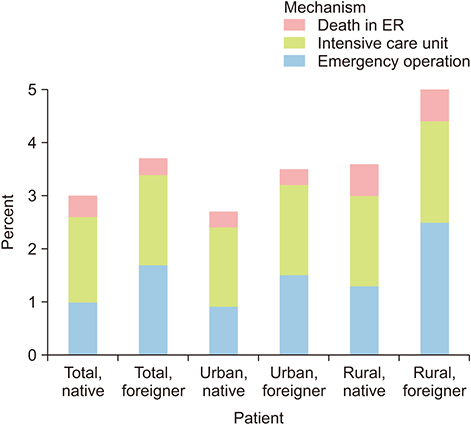

A total of 4,464,603 cases of injured patients were included, of whom 67,683 were foreign. Injury cases per 100,000 population per year were 2,960.5 for native patients and 1,659.8 for foreign patients. Foreigners were more likely to have no insurance (3.1% vs. 32.0%, p < 0.001). Serious outcomes (intensive care unit admission, emergency operation, or death) were more frequent among foreigners. In rural areas, the difference between serious outcomes for foreigners compared to natives was greater (3.7% for natives vs. 5.0% for foreigners, p < 0.001). The adjusted odds ratio for serious outcomes for foreign nationals was 1.412 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.336-1.492), and that for lack of insurance was 1.354 (95% CI, 1.314-1.394).

CONCLUSIONS

Injured foreigners might more frequently suffer serious outcomes, and health inequality was greater in rural areas than in urban areas. Foreign nationality itself and lack of insurance could adversely affect medical outcomes.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. International Organization for Migration. World migration report 2010: the future of migration: building capacities for change. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration;2010.2. Moncho J, Pereyra-Zamora P, Nolasco A, Tamayo-Fonseca N, Melchor I, Macia L. Trends and disparities in mortality among spanish-born and foreign-born populations residing in Spain, 1999–2008. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015; 17(5):1374–1384.

Article3. Korean Statistical Information Service. Population census [Internet]. Daejeon, Korea: Statistics Korea;c2019. cited at 2020 Jan 23. Available from: http://kosis.kr/eng/.4. Carballo M, Nerukar A. Migration, refugees, and health risks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001; 7:3 Suppl. 556–560.

Article5. Singh GK, Siahpush M. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001; 91(3):392–399.

Article6. Stirbu I, Kunst AE, Bos V, van Beeck EF. Injury mortality among ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60(3):249–255.

Article7. Karimi N, Beiki O, Mohammadi R. Risk of fatal unintentional injuries in children by migration status: a nationwide cohort study with 46 years' follow-up. Inj Prev. 2015; 21(e1):e80–e87.8. Tiruneh A, Siman-Tov M, Radomislensky I, Itg , Peleg K. Characteristics and circumstances of injuries vary with ethnicity of different population groups living in the same country. Ethn Health. 2017; 22(1):49–64.

Article9. Savitsky B, Aharonson-Daniel L, Giveon A, Group TI, Peleg K. Variability in pediatric injury patterns by age and ethnic groups in Israel. Ethn Health. 2007; 12(2):129–139.

Article10. Norredam M, Olsbjerg M, Petersen JH, Laursen B, Krasnik A. Are there differences in injury mortality among refugees and immigrants compared with native-born? Inj Prev. 2013; 19(2):100–105.

Article11. Cha S, Cho Y. Fatal and non-fatal occupational injuries and diseases among migrant and native workers in South Korea. Am J Ind Med. 2014; 57(9):1043–1052.

Article12. National Emergency Medical Center. Statistical yearbook of the National Emergency Department Information System 2016 [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: National Emergency Medical Center;c2019. cited at 2020 Jan 23. Available from: https://www.e-gen.or.kr/nemc/statistics_annual_report.do?brdclscd=02.13. Jeon H, Kang GH, Jang YS, Choi JT, Kim JH, Lee BJ, et al. Evaluation of emergency care for foreign patients in Korea. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2011; 22(6):735–742.14. Bos V, Kunst AE, Keij-Deerenberg IM, Garssen J, Mackenbach JP. Ethnic inequalities in age- and cause-specific mortality in The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol. 2004; 33(5):1112–1119.

Article15. Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush S. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. Am J Public Health. 2005; 95(2):224–232.

Article16. Demetriades D, Murray J, Sinz B, Myles D, Chan L, Sathyaragiswaran L, et al. Epidemiology of major trauma and trauma deaths in Los Angeles County. J Am Coll Surg. 1998; 187(4):373–383.

Article17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Work-related injury deaths among Hispanics: United States, 1992–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008; 57(22):597–600.18. Orrenius PM, Zavodny M. Do immigrants work in riskier jobs? Demography. 2009; 46(3):535–551.

Article19. Smith PM, Chen C, Mustard C. Differential risk of employment in more physically demanding jobs among a recent cohort of immigrants to Canada. Inj Prev. 2009; 15(4):252–258.

Article20. Sundquist J, Johansson SE. The influence of country of birth on mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease in Sweden 1979–1993. Int J Epidemiol. 1997; 26(2):279–287.

Article21. Wild S, McKeigue P. Cross sectional analysis of mortality by country of birth in England and Wales, 1970–92. BMJ. 1997; 314(7082):705–710.

Article22. Stirbu I, Kunst AE, Bos V, Mackenbach JP. Differences in avoidable mortality between migrants and the native Dutch in The Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6:78.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Current status of policy developments in tackling health inequalities and the next steps to be taken in Korea

- The Proposal of Policies Aimed at Tackling Health Inequalities in Korea

- Pediatric Cancer Research using Healthcare Big Data

- The Severity of the Pediatric Patients Visiting Emergency Center

- A Study on Epidemiological Factors of Burn Patients in Emergency Rooms