J Korean Foot Ankle Soc.

2019 Jun;23(2):58-66. 10.14193/jkfas.2019.23.2.58.

Risk Factors for the Treatment Failure of Antibiotic-Loaded Cement Spacer Insertion in Diabetic Foot Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. s3g1@naver.com

- KMID: 2449673

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14193/jkfas.2019.23.2.58

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To evaluate the efficacy of antibiotic-loaded cement spacers (ALCSs) for the treatment of diabetic foot infections with osteomyelitis as a salvage procedure and to analyze the risk factors of treatment failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study reviewed retrospectively 39 cases of diabetic foot infections with osteomyelitis who underwent surgical treatment from 2009 to 2017. The mean age and follow-up period were 62±13 years and 19.2±23.3 months, respectively. Wounds were graded using the Wagner and Strauss classification. X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (or bone scan) and deep tissue cultures were taken preoperatively to diagnose osteomyelitis. The ankle-brachial index, toe-brachial index (TBI), and current perception threshold were checked. Lower extremity angiography was performed and if necessary, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty was conducted preoperatively. As a surgical treatment, meticulous debridement, bone curettage, and ALCS placement were employed in all cases. Between six and eight weeks after surgery, ALCS removal and autogenous iliac bone graft were performed. The treatment was considered successful if the wounds had healed completely within three months without signs of infection and no additional amputation within six months.

RESULTS

The treatment success rate was 82.1% (n=32); 12.8% (n=5) required additional amputation and 5.1% (n=2) showed delayed wound healing. Bacterial growth was confirmed in 82.1% (n=32) with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus being the most commonly identified strain (23.1%, n=9). The lesions were divided anatomically into four groups; the largest number was the toes: (1) toes (41.0%, n=16), (2) metatarsals (35.9%, n=14), (3) midfoot (5.1%, n=2), and (4) hindfoot (17.9%, n=7). A significant difference in the Strauss wound score and TBI was observed between the treatment success group and failure group.

CONCLUSION

The insertion of ALCSs can be a useful treatment option in diabetic foot infections with osteomyelitis. Low scores in the Strauss classification and low TBI are risk factors of treatment failure.

MeSH Terms

-

Amputation

Angiography

Angioplasty

Ankle Brachial Index

Classification

Curettage

Debridement

Diabetic Foot*

Follow-Up Studies

Lower Extremity

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Metatarsal Bones

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Osteomyelitis

Retrospective Studies

Risk Factors*

Toes

Transplants

Treatment Failure*

Wound Healing

Wounds and Injuries

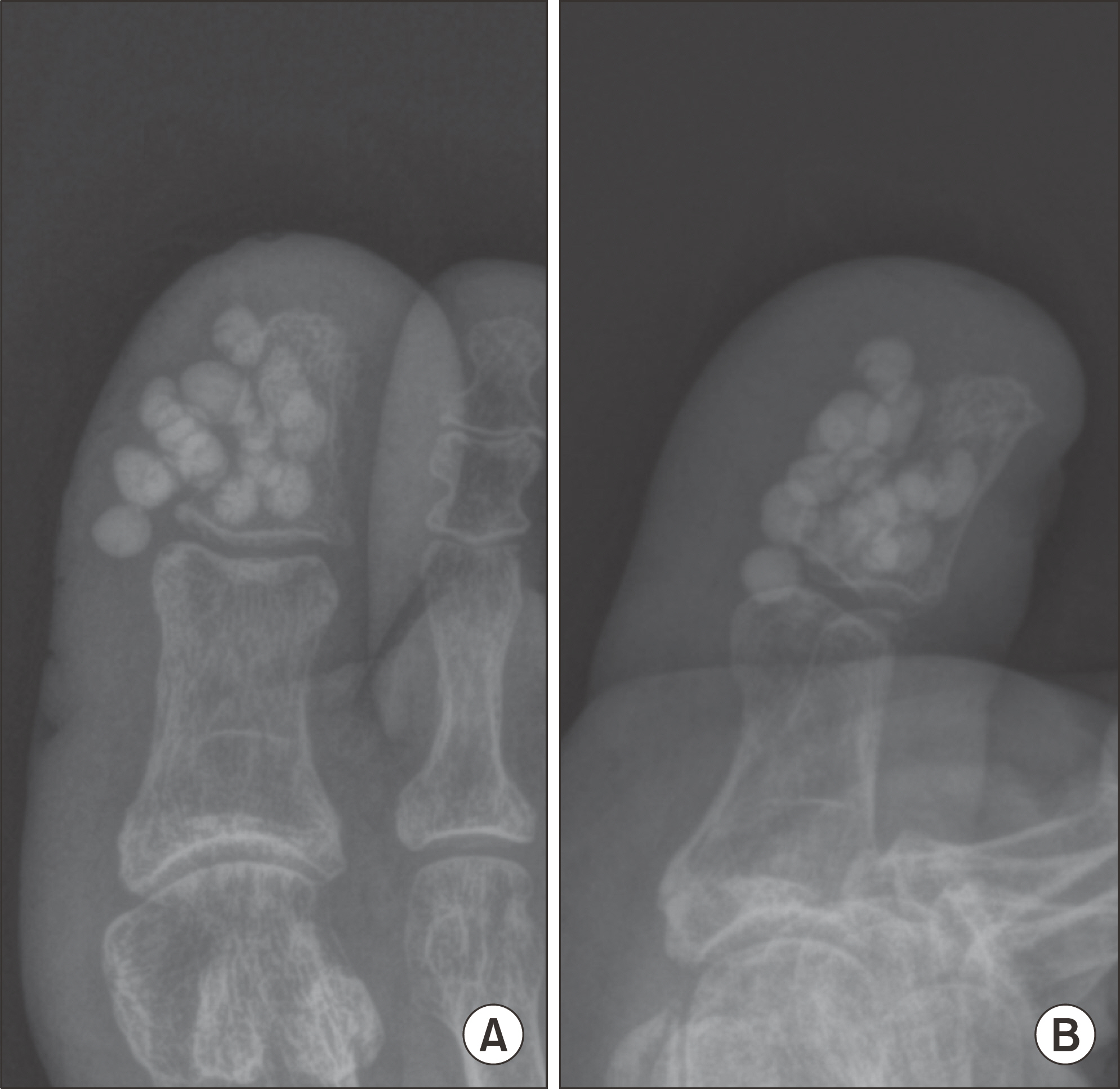

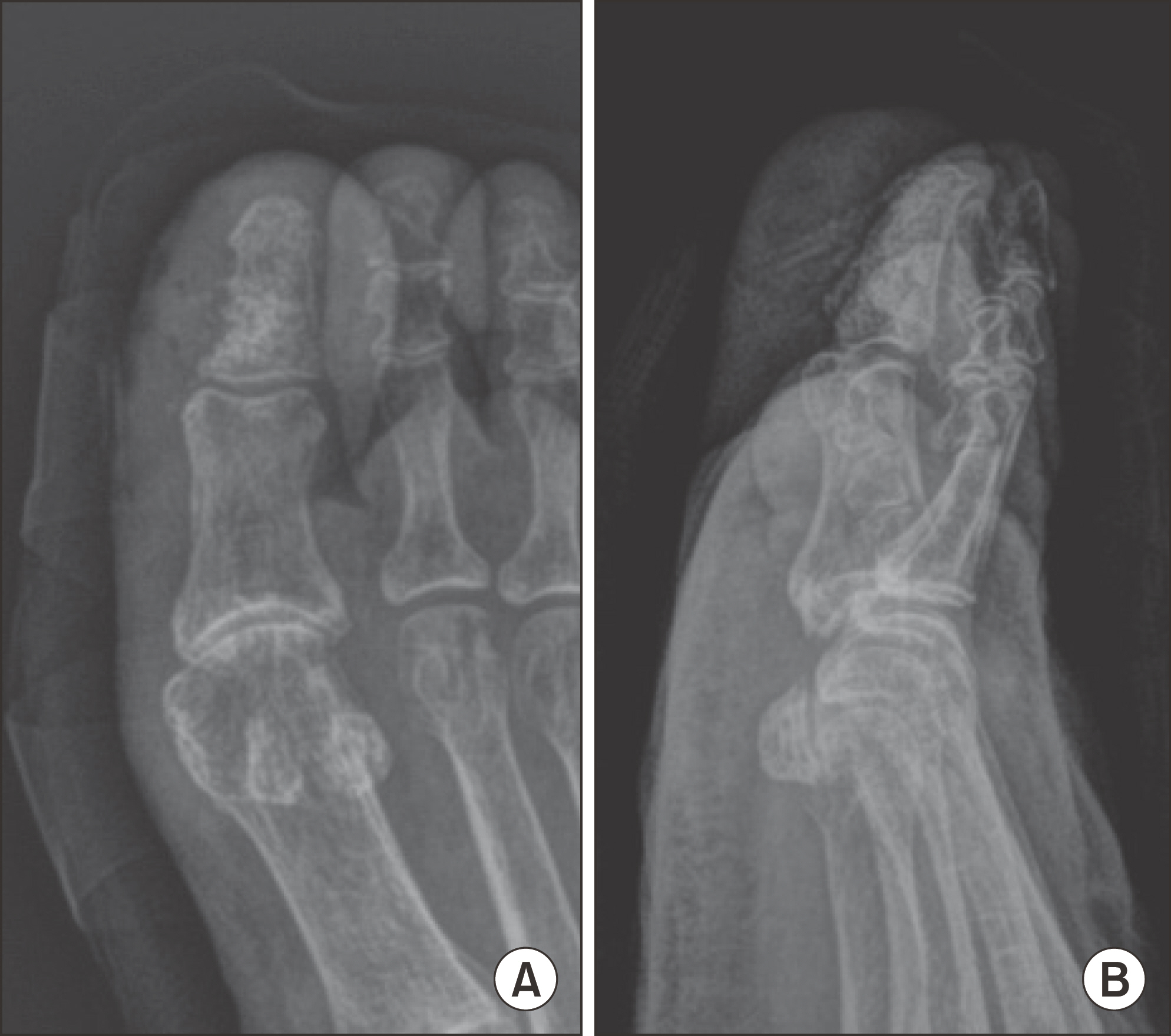

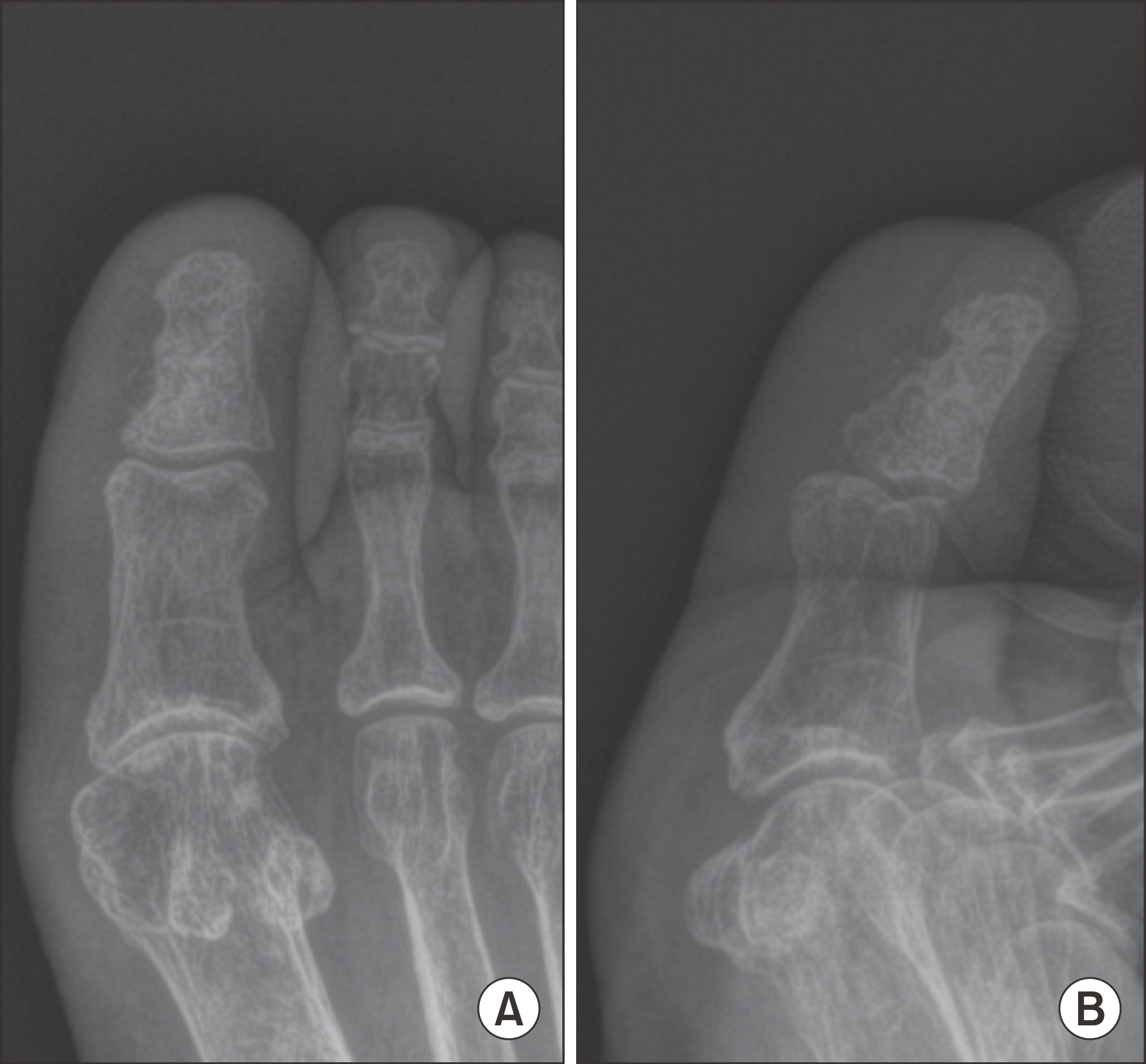

Figure

Reference

-

1.Lipsky B. Infectious problems of the foot in diabetic patients. Bowker JH, Pfeifer MA, editors. Levin and O'Neal's the diabetic foot. St. Louis (MO): Mobsy;2001. p. 467–80.

Article2.Lipsky BA. Medical treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. 39(Suppl 2):S104–14. DOI: doi: 10.1086/383271.

Article3.Frykberg RG., Wittmayer B., Zgonis T. Surgical management of diabetic foot infections and osteomyelitis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2007. 24:469–82. viii-ix.DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2007.04.001.

Article4.Dalla L., Faglia E., Caminiti M., Clerici G., Ninkovic S., Deanesi V. Ulcer recurrence following first ray amputation in diabetic patients: a cohort prospective study. Diabetes Care. 2003. 26:1874–8. DOI: doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1874.5.Izumi Y., Satterfield K., Lee S., Harkless LB. Risk of reamputation in diabetic patients stratified by limb and level of amputation: a 10-year observation. Diabetes Care. 2006. 29:566–70. DOI: doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1992.6.Sage RA. Biomechanics of ambulation after partial foot amputation: prevention and management of reulceration. J Prosthet Orthot. 2007. 19:77–9. DOI: doi: 10.1097/JPO.0b013e3180dc92fb.

Article7.Hsieh PH., Chang YH., Chen SH., Ueng SW., Shih CH. High concentration and bioactivity of vancomycin and aztreonam eluted from Simplex cement spacers in two-stage revision of infected hip implants: a study of 46 patients at an average follow-up of 107 days. J Orthop Res. 2006. 24:1615–21. DOI: doi: 10.1002/jor.20214.

Article8.Park SJ., Cho Y., Lee SW., Woo HY., Lim SE. In vitro study evaluating the antimicrobial activity of vancomycin-impregnated cement stored at room temperature in methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. J Korean Foot Ankle Soc. 2018. 22:38–43. DOI: doi: 10.14193/jkfas.2018.22.1.38.9.Buchholz HW., Engelbrecht H. [Depot effects of various antibiotics mixed with Palacos resins]. Chirurg. 1970. 41:511–5. German.10.Ostermann PA., Seligson D., Henry SL. Local antibiotic therapy for severe open fractures. A review of 1085 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995. 77:93–7. DOI: doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.77b1.7822405.

Article11.Klemm K. [Gentamicin-PMMA-beads in treating bone and soft tissue infections (author's transl)]. Zentralbl Chir. 1979. 104:934–42. German.12.Klemm K. [Local treatment of infection with gentamicin-PMMA chains and minichains]. Aktuelle Probl Chir Orthop. 1990. 34:65–77. German.13.Klemm K. The use of antibiotic-containing bead chains in the treatment of chronic bone infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001. 7:28–31.

Article14.Schade VL., Roukis TS. The role of polymethylmethacrylate antibiotic-loaded cement in addition to debridement for the treatment of soft tissue and osseous infections of the foot and ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010. 49:55–62. DOI: doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2009.06.010.

Article15.Nelson CL., Evans RP., Blaha JD., Calhoun J., Henry SL., Patzakis MJ. A comparison of gentamicin-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate bead implantation to conventional parenteral antibiotic therapy in infected total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993. 295:96–101. DOI: doi: 10.1097/00003086-199310000-00014.

Article16.Melamed EA., Peled E. Antibiotic impregnated cement spacer for salvage of diabetic osteomyelitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012. 33:213–9. DOI: doi: 10.3113/fai.2012.0213.

Article17.Elmarsafi T., Oliver NG., Steinberg JS., Evans KK., Attinger CE., Kim PJ. Long-term outcomes of permanent cement spacers in the infected foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017. 56:287–90. DOI: doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2016.10.022.

Article18.Krause FG., deVries G., Meakin C., Kalla TP., Younger AS. Outcome of transmetatarsal amputations in diabetics using antibiotic beads. Foot Ankle Int. 2009. 30:486–93. DOI: doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0486.

Article19.Roukis TS., Landsman AS. Salvage of the first ray in a diabetic patient with osteomyelitis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2004. 94:492–8. DOI: doi: 10.7547/0940492.

Article20.Lavery LA., Armstrong DG., Peters EJ., Lipsky BA. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007. 30:270–4. DOI: doi: 10.2337/dc06-1572.21.Ha Van G., Siney H., Danan JP., Sachon C., Grimaldi A. Treatment of osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Contribution of conservative surgery. Diabetes Care. 1996. 19:1257–60. DOI: doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.11.1257.

Article22.Lipsky BA., Berendt AR., Deery HG., Embil JM., Joseph WS., Karchmer AW, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Plast Re-constr Surg. 2006. 117(7 Suppl):212S–38S. DOI: doi: 10.1097/01. prs.0000222737.09322.77.

Article23.Kandemir O., Akbay E., Sahin E., Milcan A., Gen R. Risk factors for infection of the diabetic foot with multi-antibiotic resistant microorganisms. J Infect. 2007. 54:439–45. DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.08.013.

Article24.Wong MW., Hui M. Development of gentamicin resistance after gentamicin-PMMA beads for treatment of foot osteomyelitis: report of two cases. Foot Ankle Int. 2005. 26:1093–5. DOI: doi: 10.1177/107110070502601216.

Article25.Park SJ., Jung HJ., Shin HK., Kim E., Lim JJ., Yoon JW. Microbiology and antibiotic selection for diabetic foot infections. J Korean Foot Ankle Soc. 2009. 13:150–5.26.Im CS., Lee MJ., Kang JM., Cho YR., Jo JH., Lee CS. Usefulness of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty before operative treatment in diabetic foot gangrene. J Korean Foot Ankle Soc. 2018. 22:32–7. DOI: doi: 10.14193/jkfas.2018.22.1.32.

Article27.Chun DI., Jeon MC., Choi SW., Kim YB., Nho JH., Won SH. The amputation rate and associated risk factors within 1 year after the diagnosis of diabetic foot ulcer. J Korean Foot Ankle Soc. 2016. 20:121–5. DOI: doi: 10.14193/jkfas.2016.20.3.121.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Artificial Fusion of Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty Using a Flexible Intramedullary Rod Bundle and an Antibiotic-Loaded Cement Spacer

- Short-term outcomes of two-stage reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with antibiotic-loaded cement spacer for shoulder infection

- Utility of Antibiotic-Loaded Dicalcium Phosphate Dehydrate/ β-Tricalcium Phosphate in the Surgical Treatment of Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis

- Two-Stage Reimplantation of Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty with Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Spacer: Comparison of the Types of Antibiotic-Loaded Cement Spacer

- Functional Outcome after Reimplantation in Patients Treated with and without an Antibiotic-Loaded Cement Spacers for Hip Prosthetic Joint Infections