Korean Circ J.

2017 May;47(3):299-306. 10.4070/kcj.2016.0303.

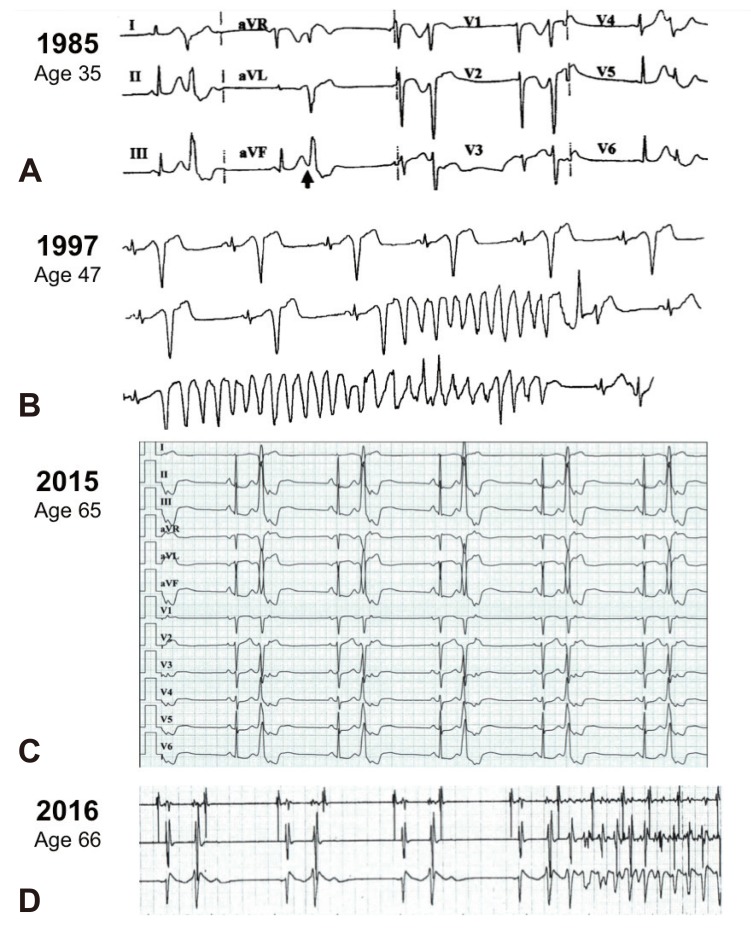

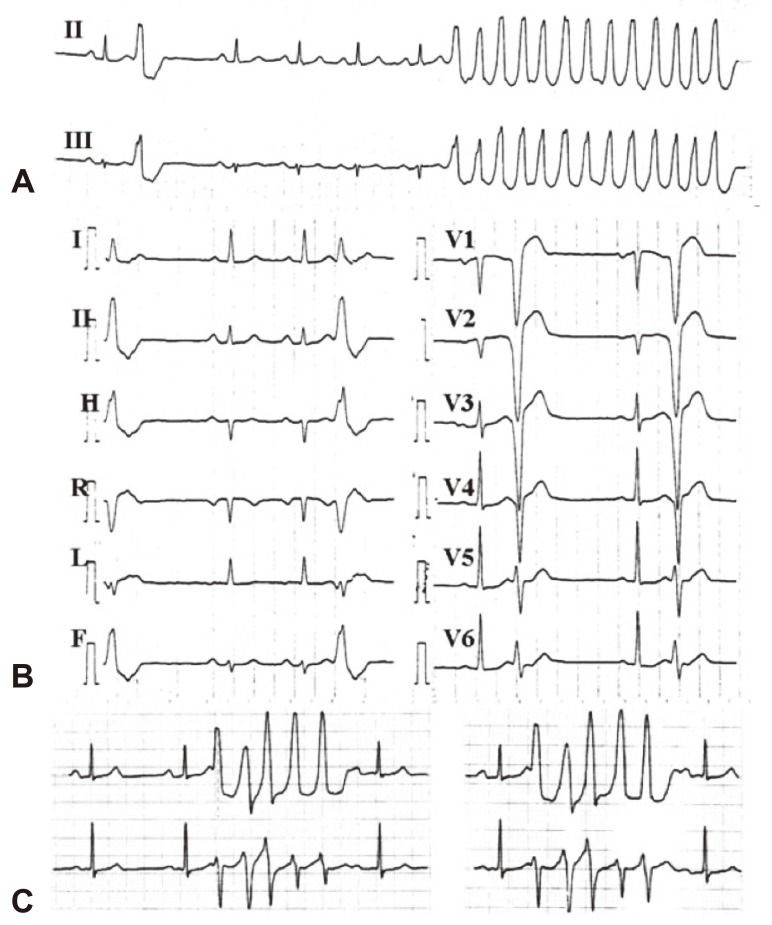

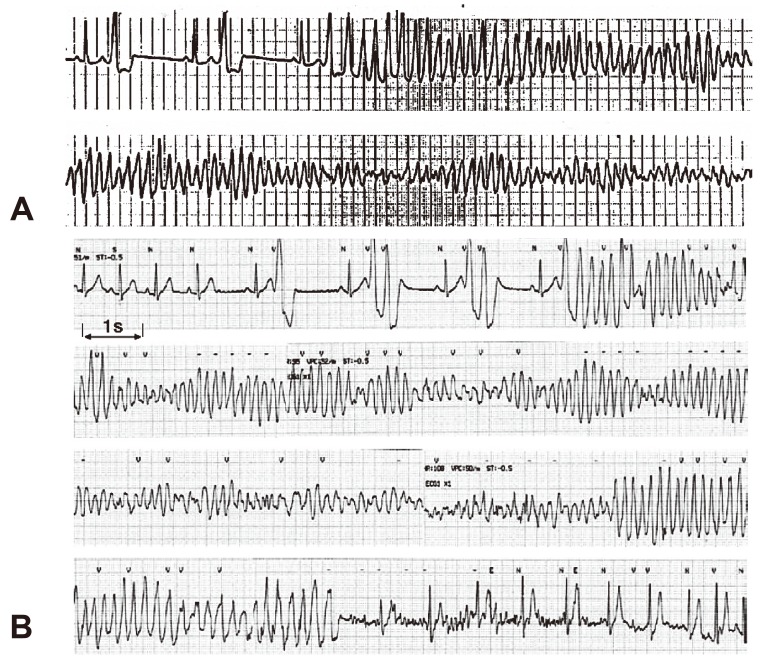

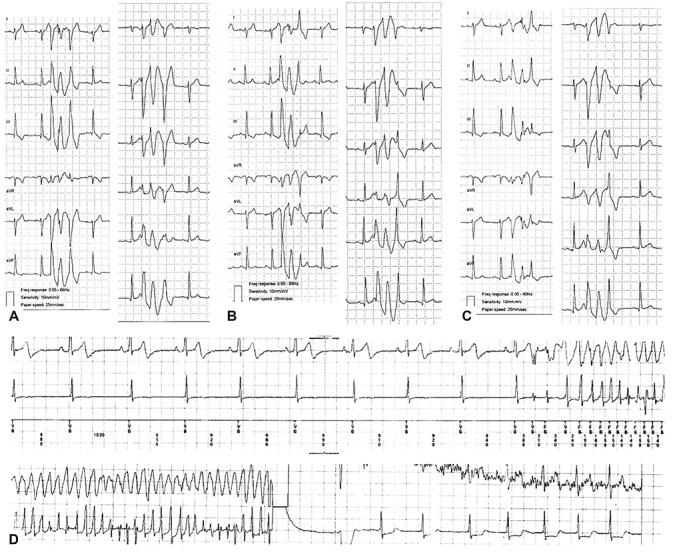

Idiopathic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: a “Benign Disease†with a Touch of Bad Luck?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center and Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. samiviskin@gmail.com

- KMID: 2385381

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.0303

Abstract

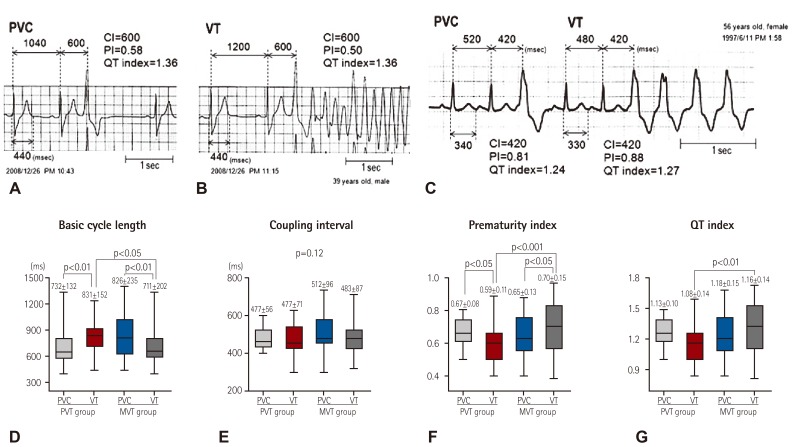

- Ventricular extrasystole originating from the right ventricular outflow tract or the left ventricular outflow tract are the most commonly encountered ventricular arrhythmias recorded in ostensibly healthy individuals with no evidence of heart disease. These ventricular arrhythmias have a distinctive electrocardiographic morphology. The morphology is so distinctive that it is common practice to accept the diagnosis of "idiopathic benign ventricular arrhythmias from the outflow tract" based on this unique morphology when the electrocardiogram during sinus rhythm and the echocardiogram are normal, sometimes removing the need to perform invasive tests in patients. Even if the outflow ventricular extrasystole ultimately triggers sustained ventricular arrhythmia, the resulting ventricular tachycardia (VT) will be a monomorphic VT originating from the outflow tract, which is known to be hemodynamically well tolerated. Thus, idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from outflow tracts are universally considered benign. In 2005, we described a rare form of malignant polymorphic VT resulting in syncope or cardiac arrest. Here, we review the literature on this topic since the emergence of initial descriptions of this intriguing phenomenon.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Is Renal Denervation Using Radiofrequency a Treatment Option for the Ventricular Arrhythmia Following Acute Myocardial Infarction?

Young Soo Lee

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(1):50-51. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2019.0361.

Reference

-

1. Belhassen B, Viskin S. Idiopathic ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1993; 4:356–368. PMID: 8269305.2. Lemery R, Brugada P, Bella PD, Dugernier T, van den Dool A, Wellens HJ. Nonischemic ventricular tachycardia. Clinical course and long-term follow-up in patients without clinically overt heart disease. Circulation. 1989; 79:990–999. PMID: 2713978.3. Biffi A, Pelliccia A, Verdile L, et al. Long-term clinical significance of frequent and complex ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 40:446–452. PMID: 12142109.4. Buxton AE, Waxman HL, Marchlinski FE, Simson MB, Cassidy D, Josephson ME. Right ventricular tachycardia: clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics. Circulation. 1983; 68:917–927. PMID: 6137291.5. Morady F, Kadish AH, DiCarlo L, et al. Long-term results of catheter ablation of idiopathic right ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1990; 82:2093–2099. PMID: 2242533.6. Takemoto M, Yoshimura H, Ohba Y, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of premature ventricular complexes from right ventricular outflow tract improves left ventricular dilation and clinical status in patients without structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:1259–1265. PMID: 15837259.7. Gaita F, Giustetto C, Di Donna P, et al. Long-term follow-up of right ventricular monomorphic extrasystoles. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38:364–370. PMID: 11499725.8. Viskin S, Rosso R, Rogowski O, Belhassen B. The “short-coupled” variant of right ventricular outflow ventricular tachycardia: a not-so-benign form of benign ventricular tachycardia? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005; 16:912–916. PMID: 16101636.9. Viskin S, Lesh M, Eldar M, et al. Mode of onset of malignant ventricular arrhythmias in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1997; 8:1115–1120. PMID: 9363814.10. Noda T, Shimizu W, Taguchi A, et al. Malignant entity of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia initiated by premature extrasystoles originating from the right ventricular outflow tract. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:1288–1294. PMID: 16198845.11. Viskin S, Antzelevitch C. The cardiologists' worst nightmare: sudden death from “benign” ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:1295–1297. PMID: 16198846.12. Michowitz Y, Viskin S, Rosso R. Exercise-induced ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation in the normal heart: risk stratification and management. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2016; 8:593–600. PMID: 27521092.13. Viskin S, Belhassen B. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1990; 120:661–671. PMID: 2202193.14. Haissaguerre M, Shoda M, Jais P, et al. Mapping and ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2002; 106:962–967. PMID: 12186801.15. Shimizu W. Arrhythmias originating from the right ventricular outflow tract: how to distinguish “malignant” from “benign”? Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:1507–1511. PMID: 19695964.16. Kurosaki K, Nogami A, Shirai Y, Kowase S. Positive QRS complex in lead i as a malignant sign in right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia: comparison between polymorphic and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ J. 2013; 77:968–974. PMID: 23238367.17. Valk SD, Dabiri-Abkenari L, Theuns DA, Thornton AS, Res JC, Jordaens L. Ventricular fibrillation and life-threatening ventricular tachycardia in the setting of outflow tract arrhythmias--the place of ICD therapy. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 165:385–387. PMID: 22989608.18. Igarashi M, Tada H, Kurosaki K, et al. Electrocardiographic determinants of the polymorphic QRS morphology in idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23:521–526. PMID: 22136173.19. Haissaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:2016–2023. PMID: 18463377.20. Rosso R, Kogan E, Belhassen B, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects incidence and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52:1231–1238. PMID: 18926326.21. Viskin S, Zeltser D, Ish-Shalom M, et al. Is idiopathic ventricular fibrillation a short QT syndrome? Comparison of QT intervals of patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and healthy controls. Heart Rhythm. 2004; 1:587–591. PMID: 15851224.22. Ramirez AH, Schildcrout JS, Blakemore DL, et al. Modulators of normal electrocardiographic intervals identified in a large electronic medical record. Heart Rhythm. 2011; 8:271–277. PMID: 21044898.23. Bradfield JS, Homsi M, Shivkumar K, Miller JM. Coupling interval variability differentiates ventricular ectopic complexes arising in the aortic sinus of valsalva and great cardiac vein from other sources: mechanistic and arrhythmic risk implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:2151–2158. PMID: 24657687.24. Uemura T, Yamabe H, Tanaka Y, et al. Catheter ablation of a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia inducing monofocal premature ventricular complex. Intern Med. 2008; 47:1799–1802. PMID: 18854632.25. Kusano KF, Yamamoto M, Emori T, Morita H, Ohe T. Successful catheter ablation in a patient with polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000; 11:682–685. PMID: 10868742.26. Takatsuki S, Mitamura H, Ogawa S. Catheter ablation of a monofocal premature ventricular complex triggering idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Heart. 2001; 86:E3. PMID: 11410580.27. Ashida K, Kaji Y, Sasaki Y. Abolition of torsade de pointes after radiofrequency catheter ablation at right ventriuclar outflow tract. Int J Cardiol. 1997; 59:171–175. PMID: 9158171.28. Kataoka M, Takatsuki S, Tanimoto K, Akaishi M, Ogawa S, Mitamura H. A case of vagally mediated idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008; 5:111–115. PMID: 18223543.29. Lerman BB, Belardinelli L, West GA, Berne RM, DiMarco JP. Adenosine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia: evidence suggesting cyclic AMP-mediated triggered activity. Circulation. 1986; 74:270–280. PMID: 3015453.30. Lerman BB, Dong B, Stein KM, Markowitz SM, Linden J, Catanzaro DF. Right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia due to a somatic cell mutation in G protein subunitalphai2. J Clin Invest. 1998; 101:2862–2868. PMID: 9637720.31. Viskin S, Rogowski O. Asymptomatic Brugada syndrome: a cardiac ticking time-bomb? Europace. 2007; 9:707–710. PMID: 17715171.32. Han J, Garcia de Jalon PD, Moe GK. Fibrillation threshold of premature ventricular responses. Circ Res. 1966; 18:18–25. PMID: 5901486.33. Sugimoto T, Schaal SF, Wallace AG. Factors determining vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation induced by 60-CPS alternating current. Circ Res. 1967; 21:601–608. PMID: 6073558.34. Robles de Medina EO, Delmar M, Sicouri S, Jalife J. Modulated parasystole as a mechanism of ventricular ectopic activity leading to ventricular fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1989; 63:1326–1332. PMID: 2471403.35. Knecht S, Sacher F, Wright M, et al. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation ablation: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:522–528. PMID: 19643313.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Interrelated Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia and Idiopathic Left Ventricular Tachycardia in a Patient with Manifested Bystander Accessory Pathway

- Ventricular Tachycardia in Neonates: A Report of Two Cases and Review of the Literature

- A Case of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

- Unusual Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Originating from the Pulmonary Artery

- Beta Blocker Sensitive Idiopathic Ventricular Tachycardia