Percentile Distributions of Birth Weight according to Gestational Ages in Korea (2010-2012)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. pedc@khnmc.or.kr

- 2Department of Medicine, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Pediatrics, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

- 4Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, Konyang University, Daejon, Korea.

- KMID: 2373704

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.6.939

Abstract

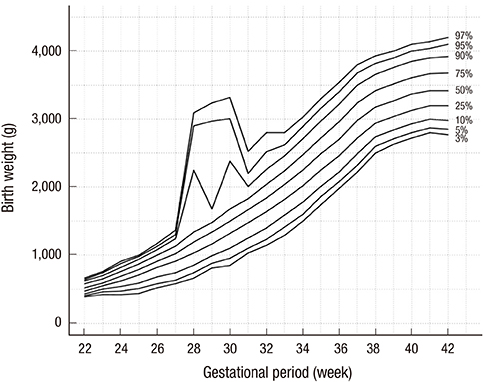

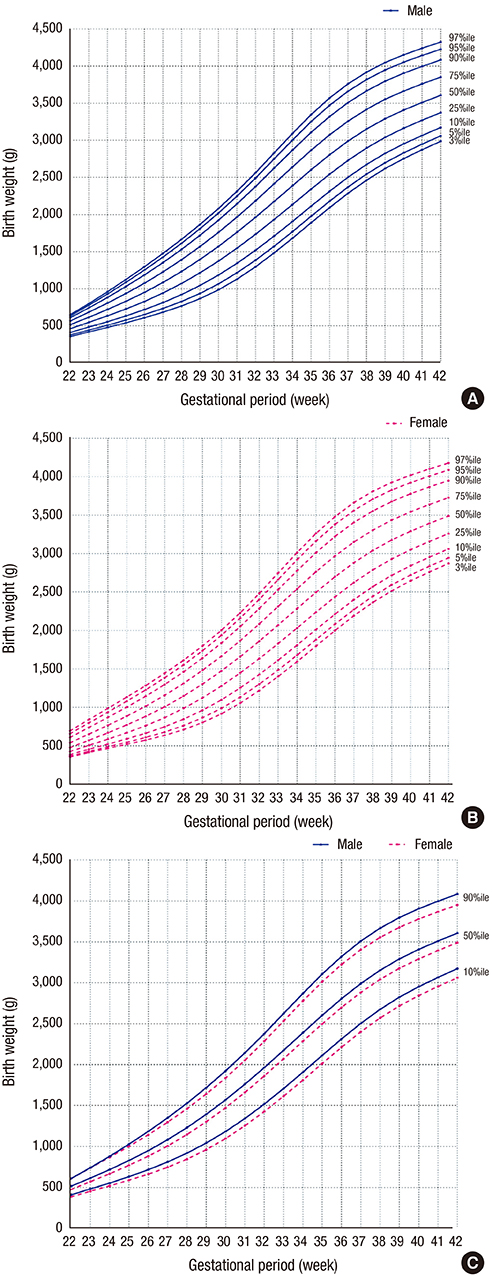

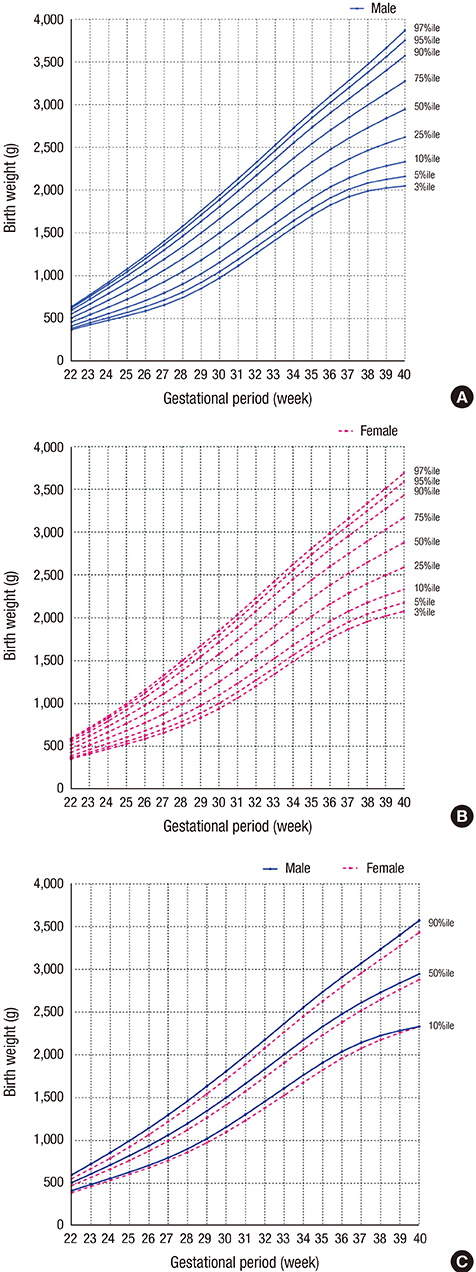

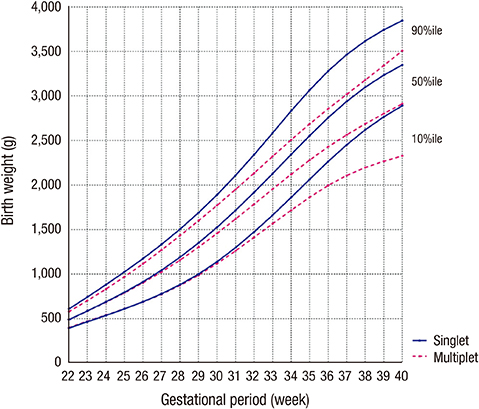

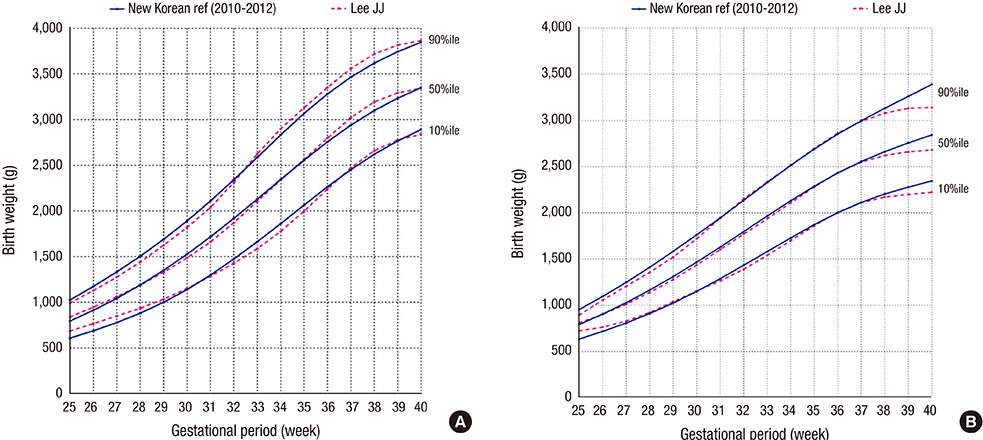

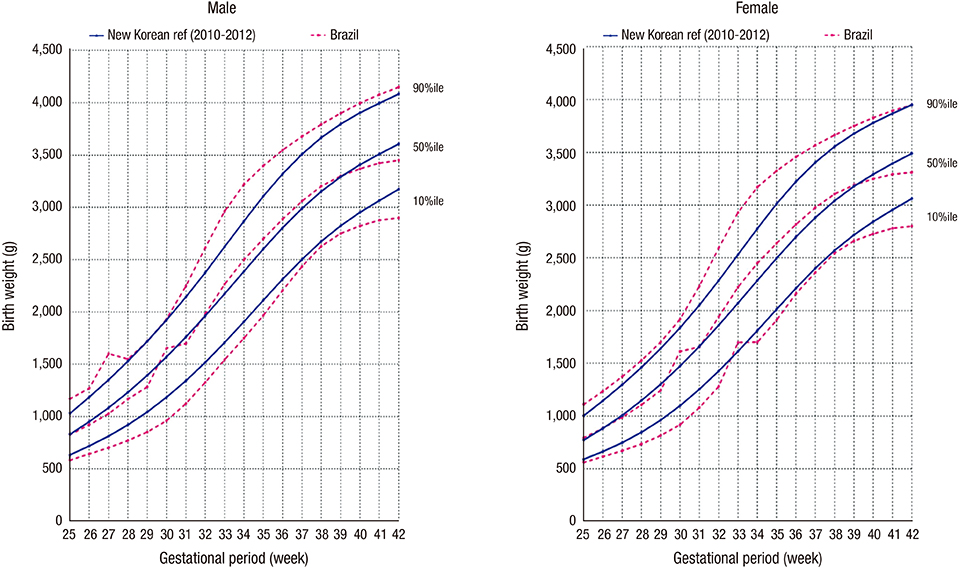

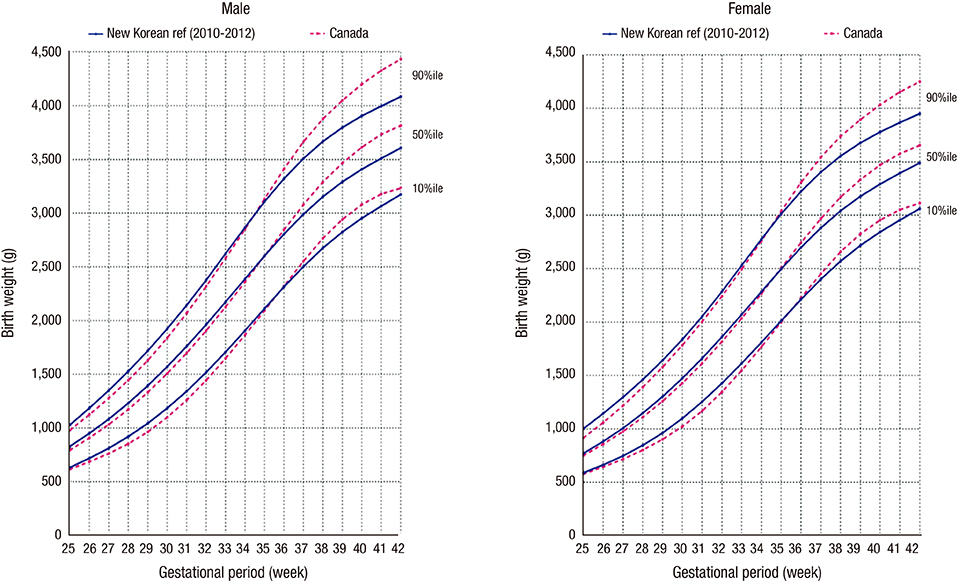

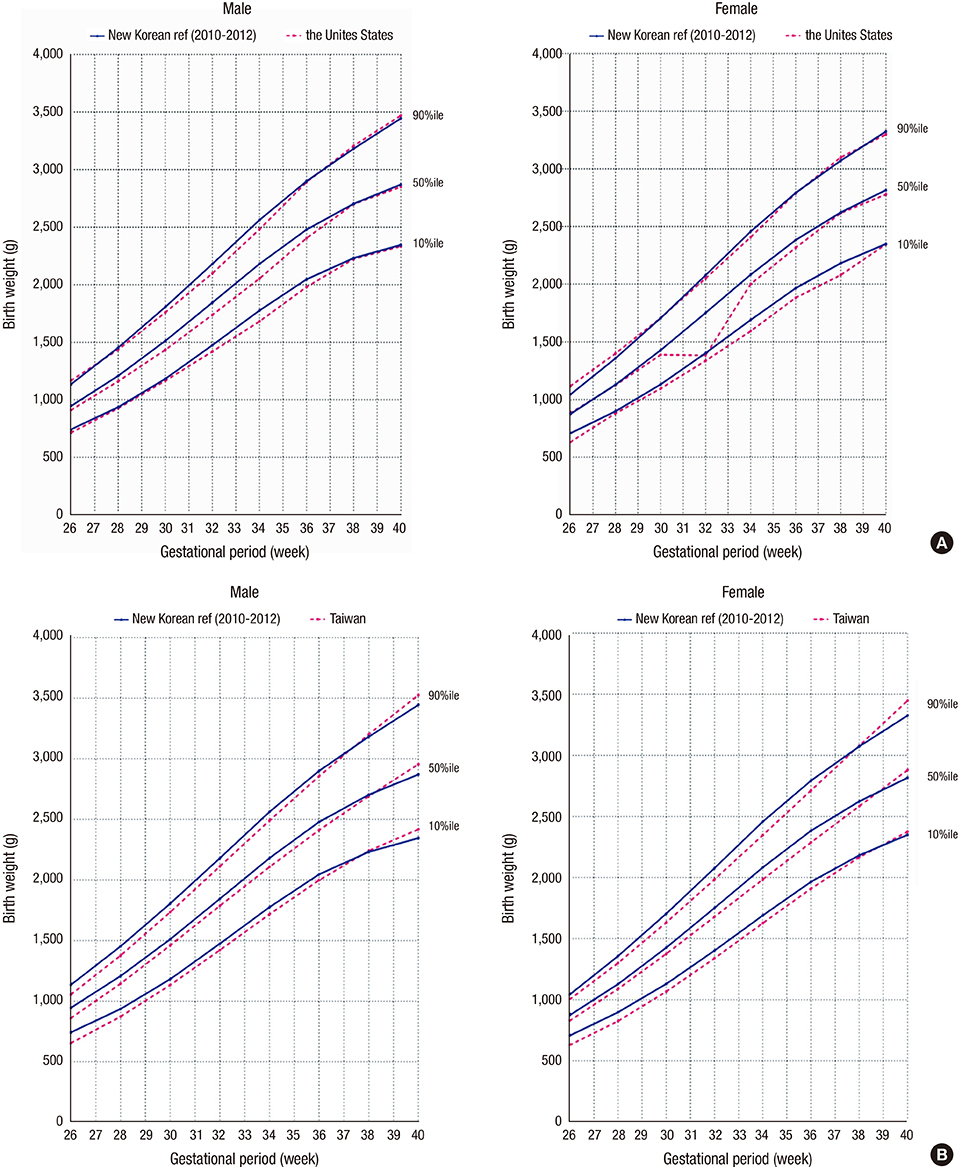

- The Pediatric Growth Chart (2007) is used as a standard reference to evaluate weight and height percentiles of Korean children and adolescents. Although several previous studies provided a useful reference range of newborn birth weight (BW) by gestational age (GA), the BW reference analyzed by sex and plurality is not currently available. Therefore, we aimed to establish a national reference range of neonatal BW percentiles considering GA, sex, and plurality of newborns in Korea. The raw data of all newborns (470,171 in 2010, 471,265 in 2011, and 484,550 in 2012) were analyzed. Using the Korean Statistical Information Service data (2010-2012), smoothed percentile curves (3rd-97th) by GA were created using the lambda-mu-sigma method after exclusion and the data were distinguished by all live births, singleton births, and multiple births. In the entire cohort, male newborns were heavier than female newborns and singletons were heavier than twins. As GA increased, the difference in BW between singleton and multiples increased. Compared to the previous data published 10 years ago in Korea, the BW of newborns 22-23 gestational weeks old was increased, whereas that of others was smaller. Other countries' data were also compared and showed differences in BW of both singleton and multiple newborns. We expect this updated data to be utilized as a reference to improve clinical assessments of newborn growth.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

Fetal Doppler to predict cesarean delivery for non-reassuring fetal status in the severe small-for-gestational-age fetuses of late preterm and term

Ji Hye Jo, Yong Hee Choi, Jeong Ha Wie, Hyun Sun Ko, In Yang Park, Jong Chul Shin

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61(2):202-208. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.2.202.Antenatal corticosteroids and outcomes of preterm small-for-gestational-age neonates in a single medical center

Woo Jeng Kim, Young Sin Han, Hyun Sun Ko, In Yang Park, Jong Chul Shin, Jeong Ha Wie

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61(1):7-13. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.1.7.Wharton Jelly Hair in a Case of Umbilical Cord Stricture and Fetal Death

Eun Na Kim, Jae-Yoon Shim, Chong Jai Kim

J Pathol Transl Med. 2019;53(2):145-147. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2018.10.24.Genetic evaluation using next-generation sequencing of children with short stature: a single tertiary-center experience

Su Jin Kim, Eunyoung Joo, Jisun Park, Chang Ahn Seol, Ji-Eun Lee

Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;29(1):38-45. doi: 10.6065/apem.2346036.018.

Reference

-

1. Babson SG, Behrman RE, Lessel R. Fetal growth. Liveborn birth weights for gestational age of white middle class infants. Pediatrics. 1970; 45:937–944.2. Thomas P, Peabody J, Turnier V, Clark RH. A new look at intrauterine growth and the impact of race, altitude, and gender. Pediatrics. 2000; 106:E21.3. Ananth CV, Wen SW. Trends in fetal growth among singleton gestations in the United States and Canada, 1985 through 1998. Semin Perinatol. 2002; 26:260–267.4. Lee JJ, Kim MH, Ko KO, Kim KA, Kim SM, Kim ER, Kim CS, Son DW, Shim JW. The study of growth measurements at different gestatioal ages of Korean newborn the survey and statistics. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2006; 13:47–57.5. Lee JJ, Park CG, Lee KS. Birth weight distribution by gestational age in Korean population: using finite mixture model. Korean J Pediatr. 2005; 48:1179–1186.6. Lee JJ. Birth weight for gestational age patterns by sex, plurality, and parity in Korean population. Korean J Pediatr. 2007; 50:732–739.7. Lim JS, Lim SW, Ahn JH, Song BS, Shim KS, Hwang IT. New Korean reference for birth weight by gestational age and sex: data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (2008-2012). Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 19:146–153.8. Chung SH, Choi YS, Bae CW. Changes in neonatal epidemiology during the last 3 decades in Korea. Neonatal Med. 2013; 20:249–257.9. Statistics Korea. Cause of death statistics, maternal death rate. Infant, Maternal and Perinatal mortality Statistics 2010~2012. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2012. p. 21–27.10. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Family Database [Internet]. 2012. accessed on 1 October 2015. Available at http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FAMILY.11. Platt RW, Abrahamowicz M, Kramer MS, Joseph KS, Mery L, Blondel B, Bréart G, Wen SW. Detecting and eliminating erroneous gestational ages: a normal mixture model. Stat Med. 2001; 20:3491–3503.12. Oja H, Koiranen M, Rantakallio P. Fitting mixture models to birth weight data: a case study. Biometrics. 1991; 47:883–897.13. Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference centile curves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Stat Med. 1992; 11:1305–1319.14. Flegal KM. Curve smoothing and transformations in the development of growth curves. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999; 70:163S–5S.15. Pedreira CE, Pinto FA, Pereira SP, Costa ES. Birth weight patterns by gestational age in Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2011; 83:619–625.16. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, Joseph KS, Allen A, Abrahamowicz M, Blondel B, Bréart G; Fetal/Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001; 108:E35.17. Min SJ, Luke B, Gillespie B, Min L, Newman RB, Mauldin JG, Witter FR, Salman FA, O'sullivan MJ. Birth weight references for twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 182:1250–1257.18. Hu IJ, Hsieh CJ, Jeng SF, Wu HC, Chen CY, Chou HC, Tsao PN, Lin SJ, Chen PC, Hsieh WS. Nationwide twin birth weight percentiles by gestational age in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015; 56:294–300.19. Lee KH. Growth assessment and diagnosis of growth disorders in childhood. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2003; 46:1171–1177.20. Lee AC, Mullany LC, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Adhikari RK, Shrestha SR, Darmstadt GL. Risk factors for neonatal mortality due to birth asphyxia in southern Nepal: a prospective, community-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008; 121:e1381–90.21. Osmond C, Barker DJ. Fetal, infant, and childhood growth are predictors of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adult men and women. Environ Health Perspect. 2000; 108:Suppl 3. 545–553.22. Goldstein H. Factors related to birth weight and perinatal mortality. Br Med Bull. 1981; 37:259–264.23. Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010; 125:e214–24.24. Roberts CL, Lancaster PA. National birthweight percentiles by gestational age for twins born in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999; 35:278–282.25. Voldner N, Frøslie KF, Godang K, Bollerslev J, Henriksen T. Determinants of birth weight in boys and girls. Hum Ontogenet. 2009; 3:7–12.26. Bleker OP, Breur W, Huidekoper BL. A study of birth weight, placental weight and mortality of twins as compared to singletons. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979; 86:111–118.27. Garite TJ, Clark RH, Elliott JP, Thorp JA. Twins and triplets: the effect of plurality and growth on neonatal outcome compared with singleton infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 191:700–707.28. Kramer MS. Socioeconomic determinants of intrauterine growth retardation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998; 52:Suppl 1. S29–32.29. Lee JH, Hahn MH, Chung SH, Choi YS, Chang JY, Bae CW, Kim YK, Kim HR. Statistic observation of marriages, births, and children in multi-cultural families and policy perspectives in Korea. Korean J Perinatol. 2012; 23:76–86.30. Kang BH, Moon JY, Chung SH, Choi YS, Lee KS, Chang JY, Bae CW. Birth statistics of high birth weight infants (macrosomia) in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2012; 55:280–285.31. Lim JW. The changing trends in live birth statistics in Korea, 1970 to 2010. Korean J Pediatr. 2011; 54:429–435.32. Blickstein I. Normal and abnormal growth of multiples. Semin Neonatol. 2002; 7:177–185.33. Ozturk O, Templeton A. In-vitro fertilisation and risk of multiple pregnancy. Lancet. 2002; 359:232.34. Imaizumi Y. A comparative study of zygotic twinning and triplet rates in eight countries, 1972-1999. J Biosoc Sci. 2003; 35:287–302.35. Ananth CV, Chauhan SP. Epidemiology of twinning in developed countries. Semin Perinatol. 2012; 36:156–161.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Clinical Features Based on Different Weight Percentile in Appropriate for Gestational Age Preterm Infants

- Birth Weight Distribution by Gestational Age in Korean Population: Using Finite Mixture Modle

- Birth Weight Distribution of Twins According to Gestational Age

- Birth weight for gestational age patterns by sex, plurality, and parity in Korean population

- New Korean reference for birth weight by gestational age and sex: data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (2008-2012)