J Dent Anesth Pain Med.

2015 Sep;15(3):173-179.

Full mouth rehabilitation of a patient with Sturge-Weber syndrome using a mixture of general and sedative anesthesia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Advanced General Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Dankook University, Cheonan, Korea.

- 2Department of Advanced General Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Anesthesiology, School of Dentistry, Dankook University, Cheonan, Korea. ksomd@dankook.ac.kr

Abstract

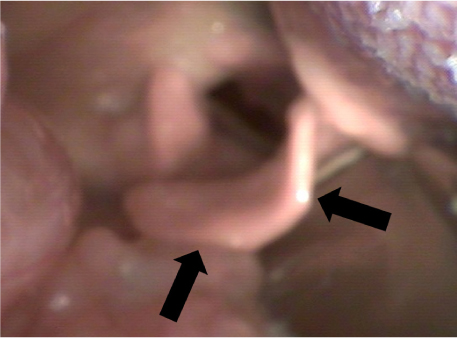

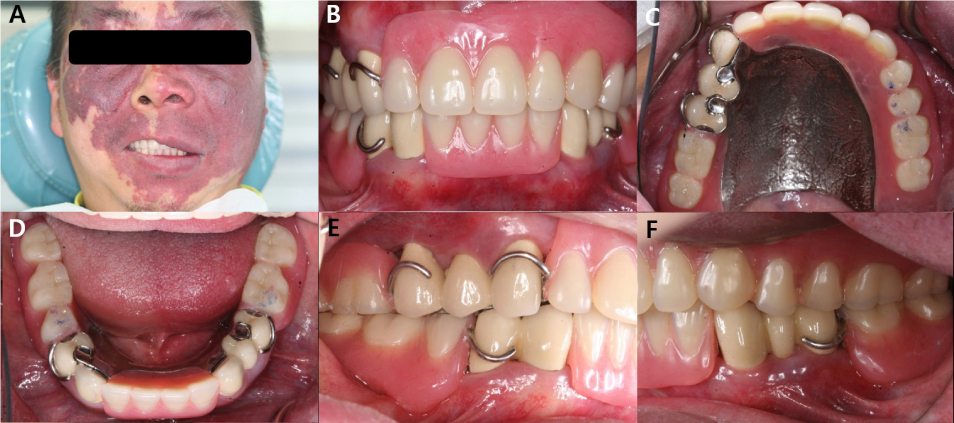

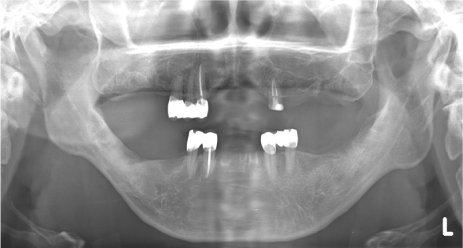

- Issues related to the control of seizures and bleeding, as well as behavioral management due to mental retardation, render dental treatment less accessible or impossible for patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS). A 41-year-old man with SWS visited a dental clinic for rehabilitation of missing dentition. A bilateral port-wine facial nevus and intraoral hemangiomatous swollen lesion of the left maxillary and mandibular gingivae, mucosa, and lips were noted. The patient exhibited extreme anxiety immediately after injection of a local anesthetic and required various dental treatments to be performed over multiple visits. Therefore, full-mouth rehabilitation over two visits with general anesthesia and two visits with target-controlled intravenous infusion of a sedative anesthesia were planned. Despite concerns regarding seizure control, bleeding control, and airway management, no specific complications occurred during the treatments, and the patient was satisfied with the results.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Roach ES. Neurocutaneous syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1992; 39:591–620.

Article2. Taly AB, Nagaraja D, Das S, Shankar SK, Pratibha NG. Sturge-weber-dimitri disease without facial nevus. Neurology. 1987; 37:1063–1064.

Article3. Thomas-Sohl KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-weber syndrome: A review. Pediatr Neurol. 2004; 30:303–310.

Article4. Suprabha BS, Baliga M. Total oral rehabilitation in a patient with portwine stains. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2005; 23:99–102.

Article5. Caiazzo A, Mehra P, Papageorge MB. The use of preoperative percutaneous transcatheter vascular occlusive therapy in the management of sturge-weber syndrome: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998; 56:775–778.

Article6. Pontes FS, Conte N, da Costa RM, Loureiro AM, do Nascimento LS, Pontes HA. Periodontal growth in areas of vascular malformation in patients with sturge-weber syndrome: A management protocol. J Craniofac Surg. 2014; 25:e1–e3.7. Yamashiro M, Furuya H. Anesthetic management of a patient with sturge-weber syndrome undergoing oral surgery. Anesth Prog. 2006; 53:17–19.

Article8. Delvi MB, Takrouri MS. Anesthesia for encephalo-trigeminal angiomatosis (sturge-weber syndrome). Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2006; 18:785–790.9. Perez DE, Pereira Neto JS, Graner E, Lopes MA. Sturge-weber syndrome in a 6-year-old girl. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005; 15:131–135.

Article10. Batra RK, Gulaya V, Madan R, Trikha A. Anaesthesia and the sturge-weber syndrome. Can J Anaesth. 1994; 41:133–136.

Article11. Butler MG, Hayes BG, Hathaway MM, Begleiter ML. Specific genetic diseases at risk for sedation/anesthesia complications. Anesth Analg. 2000; 91:837–855.

Article12. Wong HS, Abdul Rahman R, Choo SY, Yahya N. Sturge-weber-syndrome with extreme ocular manifestation and rare association of upper airway angioma with anticipated difficult airway. Med J Malaysia. 2012; 67:435–437.13. Crosby ET. An evidence-based approach to airway management: Is there a role for clinical practice guidelines? Anaesthesia. 2011; 66:Suppl 2. 112–118.

Article14. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the american society of anesthesiologists task force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2003; 98:1269–1277.15. Henderson JJ, Popat MT, Latto IP, Pearce AC. Difficult Airway Society. Difficult airway society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 2004; 59:675–694.