J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc.

2015 Nov;54(4):515-522. 10.4306/jknpa.2015.54.4.515.

The Correlation between Maternal Adult Attachment Style and Postpartum Depression and Parenting Stress

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Chung-Ang University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. sunmikim706@gmail.com

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chung-Ang University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Chung-Ang University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2149334

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2015.54.4.515

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

We aimed to determine whether the adult attachment styles of pregnant women could predict development of postpartum depression.

METHODS

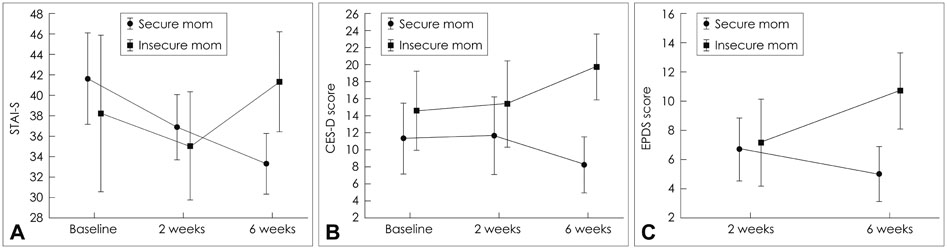

Korean version of Revised Adult Attachment Scale, State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State/Trait (STAI-S/T), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) were administered at baseline. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Parenthood Stress Questionnaire (PSQ), STAI-S, and CES-D were assessed at week 2 and 6 postpartum. Participants were categorized into the secure-mom (SM ; n=48) or insecure-mom (IM ; n=9) group.

RESULTS

While STAI-S scores in SM showed a continuous decrease during the entire observation period, STAI-S scores in IM decreased during the first two weeks but increased during the next four weeks. While SM showed decreased CES-D scores from week 2 to 6, IM showed increased CES-D scores from week 2 to 6. Although SM showed decreased EPDS scores from week 2 to 6, IM showed increased EPDS scores from week 2 to 6. In SM, the change in EDPS score from week 2 to week 6 showed positive correlation with PSQ-ability and PSQ-social subscale scores.

CONCLUSION

Assessing the maternal adult attachment style before giving birth appears to be helpful for screening the high-risk group who are vulnerable to development of postpartum depression.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Heinicke CM. Determinants of the transition to parenthood. In : Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 3. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum;1995. p. 277–303.2. Belsky J, Pensky E. Marital change across the transition to parenthood. Marriage Fam Rev. 1988; 12:133–156.

Article3. Milgrom J, McCloud P. Parenting stress and postnatal depression. Stress Med. 1996; 12:177–186.

Article4. Sadock BJ, Kaplan HI, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2007.5. Fatoye FO, Oladimeji BY, Adeyemi AB. Difficult delivery and some selected factors as predictors of early postpartum psychological symptoms among Nigerian women. J Psychosom Res. 2006; 60:299–301.

Article6. O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risks of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996; 8:37–54.7. Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper P. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Dev. 1996; 67:2512–2526.

Article8. Cummings EM, Davies PT, Simpson KS. Marital conflict, gender, and children's appraisal and coping efficacy as mediators of child adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 1994; 8:141–149.

Article9. Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: a meta-analytic investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000; 41:737–746.

Article10. Kelly R, Zatzick D, Anders T. The detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders and substance use among pregnant women cared for in obstetrics. Am J Psychiatry. 2001; 158:213–219.

Article11. Kahn JH, Garrison AM. Emotional self-disclosure and emotional avoidance: relations with symptoms of depression and anxiety. J Couns Psychol. 2009; 56:573–584.

Article12. Angold A, Costello EJ. Developmental epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1995; 17:74–82.

Article13. Hoghughi M, Speight AN. Good enough parenting for all children--a strategy for a healthier society. Arch Dis Child. 1998; 78:293–296.

Article14. Perris C, Arrindell WA, Eisemann M. Parenting and psychopathology. England: J. Wiley;1994.15. Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987; 52:511–524.

Article16. Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990; 58:644–663.

Article17. Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991; 61:226–244.

Article18. Fonagy P, Steele M, Moran G, Steele H, Higgitt A. Measuring the ghost in the nursery: an empirical study of the relation between parents' mental representations of childhood experiences and their infants' security of attachment. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1993; 41:957–989.

Article19. Blackmore ER, Carroll J, Reid A, Biringer A, Glazier RH, Midmer D, et al. The use of the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) tool in the detection of psychosocial risk factors for postpartum depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006; 28:873–878.

Article20. Kim EJ, Kwon JH. Interpersonal characteristics related with depressive symptoms focused on adult attachment. J Korean Clin Psychol. 1998; 17:139–153.21. Kim MH, Kim MS. The influence of adult attachment on depression, self-esteem, empathy in female college students with a major in health science. J Soc Sci. 2013; 29:23–37.22. Shin NR, Ahn CY. The relationships among adult attachment styles, social anxiety, self-concept, self-efficacy, coping strategy, and social support. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2004; 23:949–968.23. Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991; 20:149–166.

Article24. Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998; 186:304–310.

Article25. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press;1970.26. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150:782–786.27. Han KW, Kim MG, Park JM. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, Korean version: reliability and validity. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2004; 10:201–207.28. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961; 4:561–571.

Article29. Ahn YM, Kim JH. Comparison of maternal self-esteem, postpartal depression, and family function in mothers of normal and of low birth-weight infants. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2003; 33:580–590.

Article30. Abidin RR, Wilfong E. Parenting stress and its relationship to child health care. Child Health Care. 1989; 18:114–116.

Article31. Ostberg M. Parental stress, psychosocial problems and responsiveness in help-seeking parents with small (2-45 months old) children. Acta Paediatr. 1998; 87:69–76.

Article32. Ostberg M, Hagekull B, Wettergren S. A measure of parental stress in mothers with small children: dimensionality, stability and validity. Scand J Psychol. 1997; 38:199–208.

Article33. Beck CT. Theoretical perspectives of postpartum depression and their treatment implications. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2002; 27:282–287.

Article34. Ahn YM, Kim MR. The effects of a home-visiting discharge education on maternal self-esteem, maternal attachment, postpartum depression and family function in the mothers of NICU infants. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004; 34:1468–1476.

Article35. Kim JI. A validation study on the translated Korean version of the Edinbergh Postnatal Depression Scale. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2006; 12:204–209.

Article36. George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Adult Attachment Interview. California: University of California, Berkeley, Department of Psychology;1985.37. Chen CH, Tseng YF, Wang SY, Lee JN. The prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression. J Nurs Res. 1994; 2:263–274.38. Levy-Shiff R. Individual and contextual correlates of marital change across the transition to parenthood. Deve Psychol. 1994; 30:591–601.

Article39. Gelfand DW, Teti DM, Fox CER. Sources of parenting stress for depressed and nondepressed mothers of infants. J Clin Child Psychol. 1992; 21:262–272.

Article40. Hung CH, Chung HH. The effects of postpartum stress and social support on postpartum women's health status. J Adv Nurs. 2001; 36:676–684.

Article41. O'Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991; 100:63–73.42. Hopkins J, Campbell SB, Marcus M. Role of infant-related stressors in postpartum depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987; 96:237–241.

Article43. Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008; 8:24.

Article44. Nonacs RM, Soares CN, Viguera AC, Pearson K, Poitras JR, Cohen LS. Bupropion SR for the treatment of postpartum depression: a pilot study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005; 8:445–449.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Differences in Parenting Stress, Parenting Attitudes, and Parents' Mental Health According to Parental Adult Attachment Style

- Postpartum Depression and Maternal Role Confidence, Parenting Stress, and Infant Temperament in Mothers of Young Infants

- The Relationship between Depressive Tendency in Postpartum Women and Factors such as Infant Temperament, Parentiong Stress and Coping Style

- Effects of Maternal Sociodemographic Characteristics and Parenting Stress on a Child's Self-Concept: Parenting Style as a Mediating Factor

- The Relationship between Early Neo-maternal Exposure, and Maternal Attachment, Maternal Self-esteem and Postpartum Depression in the Mothers of NICU Infants