Korean J Phys Anthropol.

2015 Sep;28(3):127-136. 10.11637/kjpa.2015.28.3.127.

Aristotelian Philosophy in Its Bearing on Anatomical Thought

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anatomy, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, Korea. asch@jbnu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2068823

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11637/kjpa.2015.28.3.127

Abstract

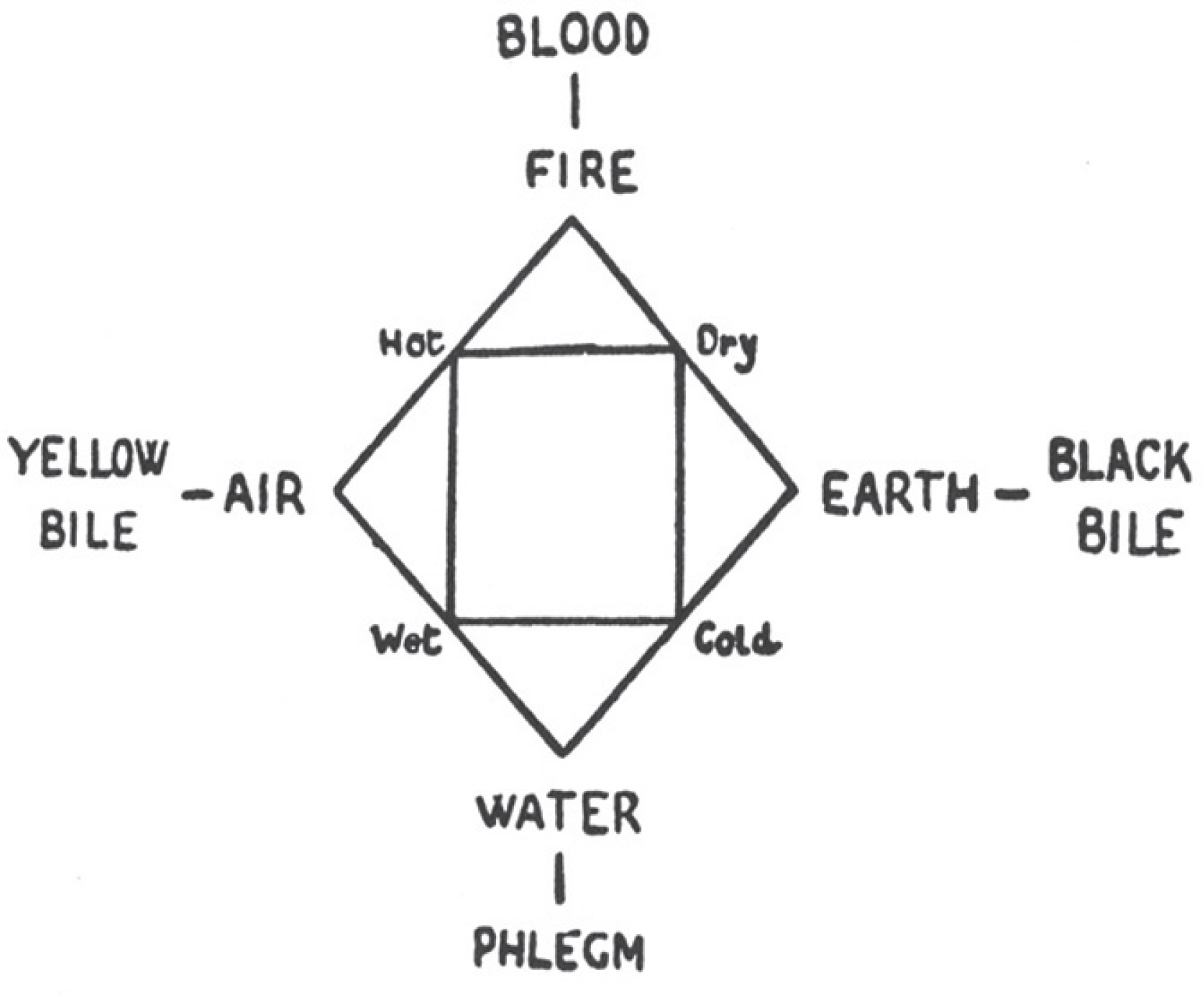

- Although Aristotle is commonly known as a theoretical philosopher and a logician, he was also a great natural scientist. Actually in modern terms he was the first ever anatomist who originated anatomy. Despite the fact that he didn't directly dissect humans, he observed parts of fetus and tried systematic analysis of animal bodies. The achievements he has accomplished in human anatomy and animal comparative anatomy are countless. He accurately described organs and built a foundation for presenting scientific reasons in anatomical research. Furthermore, he made modern nomenclature which is still being used today and his observational skills were so precise it was hard to even believe. Even though there were a lot of errors in his physiological concepts, his structural descriptions about organs and body parts were the best at that time. The aim of this article is to discuss how Aristotle's anatomy and philosophy are closely related. It's aim is to take a look at his anatomical achievements, errors and Aristotelian philosophy in its bearing on anatomical thoughts. In addition, the goal is to knowledge today's anatomists about Aristotle's astonishing achievements as a great pioneer in anatomy.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Persaud TVN. Early history of human anatomy. Spring-field, Illinois: Charles C Thomas Publisher;1984. p. 38–43.2. McLeisch KC. Aristotle: The great philosophers. Rout-ledge;1999. p. 5.3. Singer C. A short history of anatomy and physiology from the Greeks to Harvey. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.;1957. p. 17–28.4. Crivellato E, Ribatti D. A portrait of Aristotle as an anato-mist: Historical article. Clin Anat. 2007; 20:477–85.

Article5. Jaeger W. Aristoteles: Grundlegung einer Geschichte seiner Entwicklung (1923;English trans. by Richard Robinson as Aristotle: Fundamentals of the History of His Develop-ment. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934. (Dennes WR, Philosophical Review. 1937; 46:326–9. .).6. Boudjeltia KZ, Lelubre C. Relations between the scientific thought and the medicine: the contributions of Plato and Aristotle. Rev Med Brux. 2015; 36:52–7.7. Moor KL, Dalley AF. Clinically oriented anatomy. 4th ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;1999. p. 2.8. Aristotle. De Generatione Animalium: On the Generation of Animals by Hendrik Joan Lulofs, Oxford University Press; Oxford Classical Texts edition. 2006. 10–21.9. Pierre P. Aristotle's classification of animals: Biology and the conceptual unity of the Aristotelian corpus. Translated by Anthony Preus. University of California Press. 1986. 1–12.10. Aristotle. The History of Animals. Translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson. eBooksAdelaide. 2014. 1–17.11. Lennox JG. Aristole on genera, species, and “the more and the less”. J Hist Biol. 1980; 13:321–46.12. Grene M. Aristotle and modern biology. J Hist Ideas. 1972; 33:395–9.

Article13. Harris CRS. The heart and the vascular system in ancient Greek medicine. Oxford: Clarendon;1973. p. 83.14. Shaw JR. Models for cardiac structure and function in Aristotle. J Hist Biol. 1972; 5:355–80.

Article15. Fitting JW. From breathing to respiration. Respiration. 2015; 89:82–7.

Article16. Tsuchiya R1. Kuroki T, Eguchi S. The pancreas from Aristotle to Galen. Pancreatology. 2015; 15:2–7.17. Clarke E, Stannard J: Aristotle on the anatomy of the brain. J Hist Med. 1963; 18:130–6.18. Clarke E. Aristotelian concepts of the form and function of the brain. Bull Hist Med. 1963; 37:1–7.19. Koelbing H. Zur Sehtheorie im Altertum: Alkmeon und Ar-istoteles. Gesnerus(Aarau). 1968; 25:5–10.20. Sorabji R. Aristotle on demarcating the five senses. Philos Rev. 1970; 80:55–61.

Article21. Staden von H. Herophilus: The art of medicine in early alexandria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;1989. p. 157 and p.p. 173.22. Lloyd GER. Early Greek science: Thales to Aristotle. New York/London: Norton;1970. p. 116.23. Lonie IM. Erasistratus, the Erasistrateans and Aristotle. Bull Hist Med. 1964; 38:426–31.24. Bandeokjjin. The discovery of Hippocrates. Seoul: Human-ist;2005. p. 274–81. Korean.25. Garrison AB. History of medicine. 4th ed.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.;1929. p. 101–2.26. Preuss A. Science and philosophy in Aristotle's “Generation of animals.” J Hist Biol. 1970; 3:1–8.27. Lennox JG. Recent Philosophical Studies of Aristotle's Biology. Ancient Philosophy. 1984; 4:73–82.

Article28. Yu wonki. Aristotle's theory of mind and body and modern philosophical psychology. Philosophy. 2003; 76:105–27. Korean.29. http://info.catholic.or.kr/bible/30. Barnes J. Aristotle. Oxford: Oxford University Press;1982. p. 110–5.31. Cunningham A. The anatomical renaissance. The resurrection of the anatomical projects of the ancients. Hants: Sco-lar Press;1997. p. 13–22. and p. 167–87.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Han-Thought and Nursing

- The Philosophy and Medicinal Thought of Dong Mu Lee Jae-Ma

- The Medical Philosophy of Choe Han-Ki

- A Comparison of Radiographs of the Hallux Valgus and Normal Foot in Women over Forty Years Old on Weight-bearing and Wonweight-bearing

- Origin and precondition of medical self-regulation: State philosophy and medical professionalism in France