Korean J Ophthalmol.

2005 Sep;19(3):183-188. 10.3341/kjo.2005.19.3.183.

The Effects of Laser Photocoagulation on Reopened Macular Holes, as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. swkang@smc. samsung.co.kr

- KMID: 754422

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2005.19.3.183

Abstract

- PURPOSE

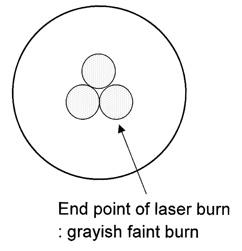

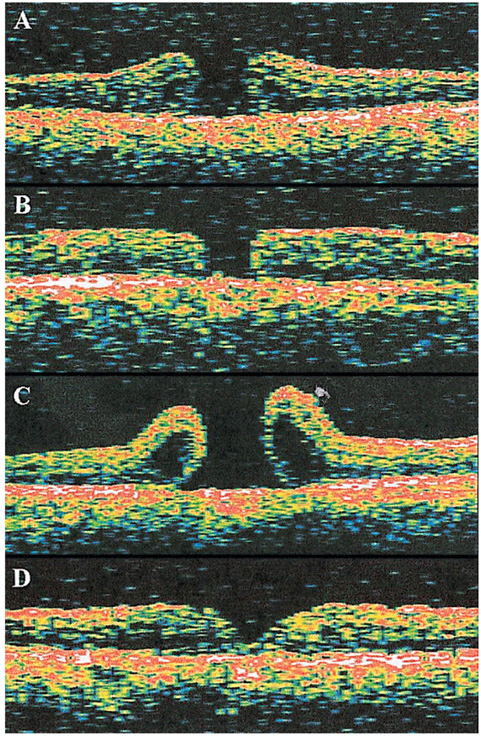

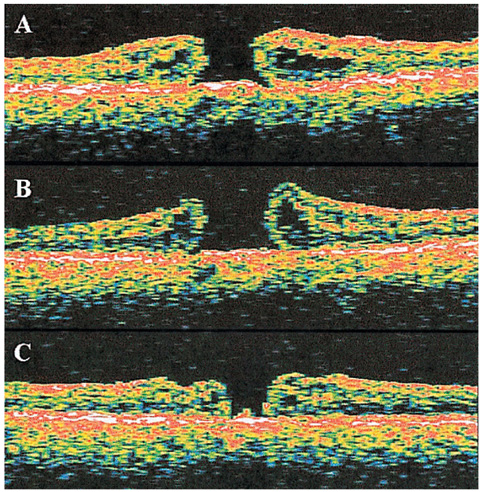

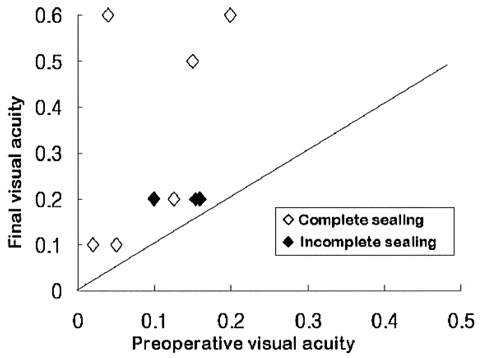

To evaluate the effects of laser photocoagulation on reopened macular holes. METHODS: This study involved 9 eyes from 9 patients who underwent laser photocoagulation coupled with fluid-gas exchange for reopened macular holes. The photocoagulation was performed at the center of the macular hole. Closure of the reopened hole was categorized by optical coherence tomography (OCT) according to the presence (type 1 closure) or absence (type 2 closure) of continuity in the foveal tissue. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), closure types, and complications were assessed. RESULTS: Upon final examination, all macular holes were found to have closed. Six eyes were classified as type 1 closure, and three were classified as type 2 closure. The mean BCVAs, before and after laser photocoagulation, were 0.11 and 0.31, respectively (P< .05). The eyes with type 1 closure were associated with shorter symptom durations and greater visual improvement than those with type 2 closure (P< .05). CONCLUSIONS: The combination of laser photocoagulation and fluid-gas exchange appears to be a safe and effective treatment for reopened macular holes. Early intervention should be encouraged to ensure complete hole closure and improved visual outcomes.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Delayed Closure of Idiopathic Macular Hole after Vitrectomy, Internal Limiting Membrane Peeling, and Gas Tamponade

Jong Heon Lee, Ho Yun Kim, Sung Who Park, Ji Eun Lee, Ik Soo Byon

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2014;55(5):775-779. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2014.55.5.775.

Reference

-

1. Kelly NE, Wendel RT. Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes. Results of a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991. 109:654–659.2. Wendel RT, Patel AC, Kelly NE, et al. Vitreous surgery for macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1993. 100:1671–1676.3. Freeman WR, Azen SP, Kim JW, et al. The Vitrectomy for Treatment of Macular Hole Study Group. Vitrectomy for the treatment of full-thickness stage 3 or 4 macular holes. Results of a multicentered randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997. 115:11–21.4. Thompson JT, Smiddy WS, Williams GA, et al. Comparison of recombinant transforming growth factor-beta-2 and placebo as an adjunctive agent for macular hole surgery. Ophthalmology. 1998. 105:700–706.5. Min WK, Lee JH, Ham DI. Macular hole surgery in conjunction with endolaser photocoagulation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999. 127:306–311.6. Park SS, Marcus DM, Duker JS, et al. Posterior segment complications after vitrectomy for macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1995. 102:775–781.7. Christmas NJ, Smiddy WE, Flynn HW Jr. Reopening of macular holes after initially successful macular hole surgery. Ophthalmology. 1997. 104:1648–1652.8. Paques M, Massin P, Blain P, et al. Long-term incidence of reopening of macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2000. 107:760–766.9. Paques M, Massin P, Santiago PY, et al. Late reopening of successfully treated macular holes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997. 81:658–662.10. Ezra E, Aylward WG, Gregor ZJ. Membranectomy and autologous serum for the retreatment of full-thickness macular holes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997. 115:1276–1280.11. Ie D, Glaser BM, Thompson JT, et al. Retreatment of full-thickness macular holes persisting after prior vitrectomy. Ophthalmology. 1993. 100:1787–1793.12. Thompson JT, Sjaarda RN. Surgical treatment of macular holes with multiple recurrence. Ophthalmology. 2000. 107:1073–1077.13. Smiddy WE, Sjaarda RN, Glaser BM, et al. Reoperation after failed macular hole surgery. Retina. 1996. 16:13–18.14. Johnson RN, Mcdonald HR, Schatz H, Ai E. Outpatient postoperative fluid gas exchange after early failed vitrectomy surgery for macular hole. Ophthalmology. 1997. 104:2009–2013.15. Del Priore LV, Kaplan HJ, Bonham RD. Laser photocoagulation and fluid-gas exchange for recurrent macular hole. Retina. 1994. 14:381–382.16. Ikuno Y, Kamei M, Saito Y, et al. Photocoagulation and fluid-gas exchange to treat persistent macular holes after prior vitrectomy. A pilot study. Ophthalmology. 1998. 105:1411–1418.17. Ohana E, Blumenkranz MS. Treatment of reopened macular hole after vitrectomy by laser and outpatient fluid-gas exchange. Ophthalmology. 1998. 105:1398–1403.18. Kang SW, Ahn K, Ham DI. Types of macular hole closure and their clinical implications. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003. 87:1015–1019.19. Schocket SS, Lakhanpal V, Miao XP. Laser treatment of macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1988. 95:574–582.20. Matsumoto M, Yoshimura N, Honda Y. Increased production of transforming growth factor-beta 2 from cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells by photocoagulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994. 35:4245–4252.21. Willis AW, Garcia-Cosio JF. Macular hole surgery. Comparison of longstanding versus recent macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1996. 103:1811–1814.22. Ullrich S, Haritoglou C, Gass C, et al. Macular hole size as a prognostic factor in macular hole surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002. 86:390–393.23. Amari F, Ohta K, Kojima H, et al. Predicting visual outcome after macular hole surgery using scanning laser ophthalmoscope microperimetry. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001. 85:96–98.24. Nao-I N, Matsuura Y, Arai M, et al. Modified vitreous surgery for full-thickness macular hole. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 1994. 48:1989–1994.25. Sjaarda RN, Frank DA, Glaser BM, et al. Resolution of an absolute scotoma and improvement of relative scotomata after successful macular hole surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993. 116:129–139.26. Glaser BM, Michels RG, Kuppermann BD, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta2 for the treatment of full-thickness macular holes. A prospective randomized study. Ophthalmology. 1992. 99:1162–1172.27. Paques M, Chastang C, Mathis A, et al. Effect of autologous platelet concentrate in surgery for idiopathic macular hole. Results of a multicenter, double-masked, randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 1999. 106:932–938.28. Liggett PE, Skolik DS, Horio B, et al. Human autologous serum for the treatment of full-thickness macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1995. 102:1071–1076.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Laser Photocoagulation as Adjuvant Therapy to Surgery for Large Macular Holes

- Comparison of Effects of IVTA and Photocoagulation, Depending on Types of Diabetic Macular Edema

- The Clinical Manifestations and Treatments of Parafoveal Telangiectasis

- Optical Coherence Tomographic Evaluation of Impending Idiopathic Macular Hole Repaired by Vitrectomy

- Change in Subfoveal Choroidal Thickness after Argon Laser Panretinal Photocoagulation