Korean Circ J.

2022 Nov;52(11):829-843. 10.4070/kcj.2022.0156.

Trends in Regional Disparity in Cardiovascular Mortality in Korea, 1983–2019

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Public Health, Yonsei University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea

- 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea

- 4Institute for Innovation in Digital Healthcare, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2534903

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2022.0156

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

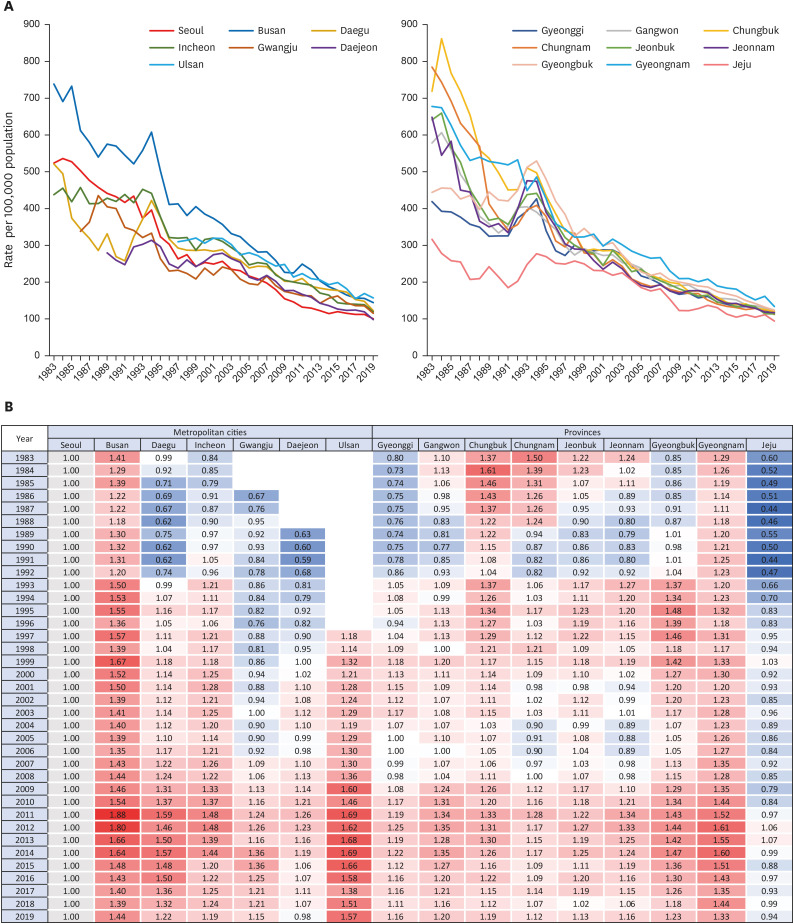

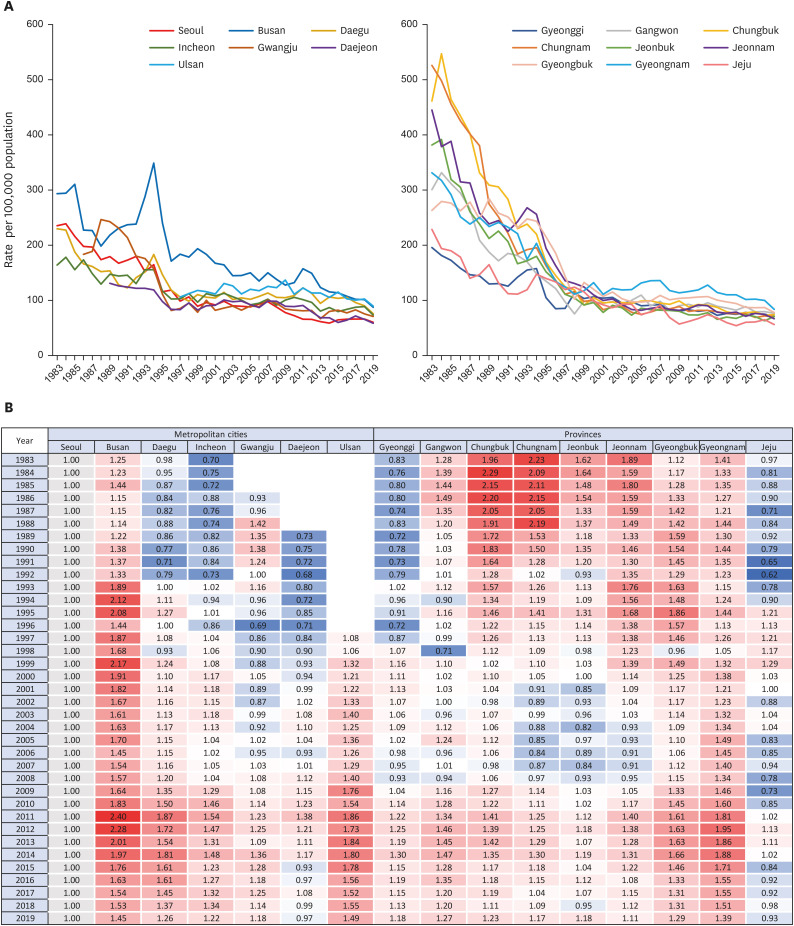

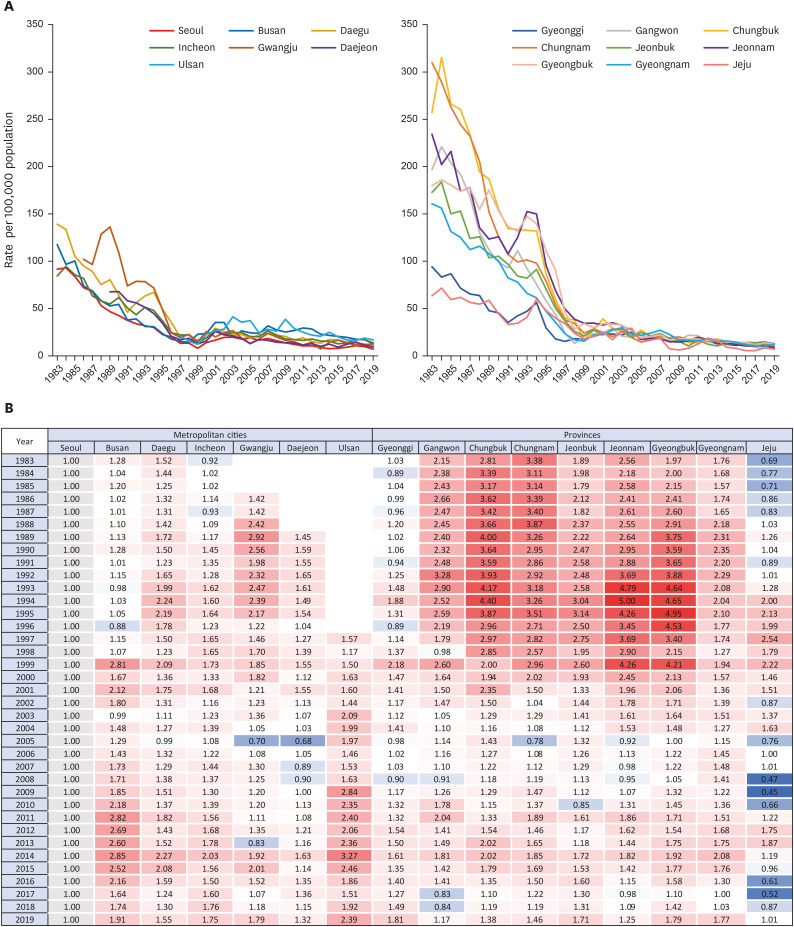

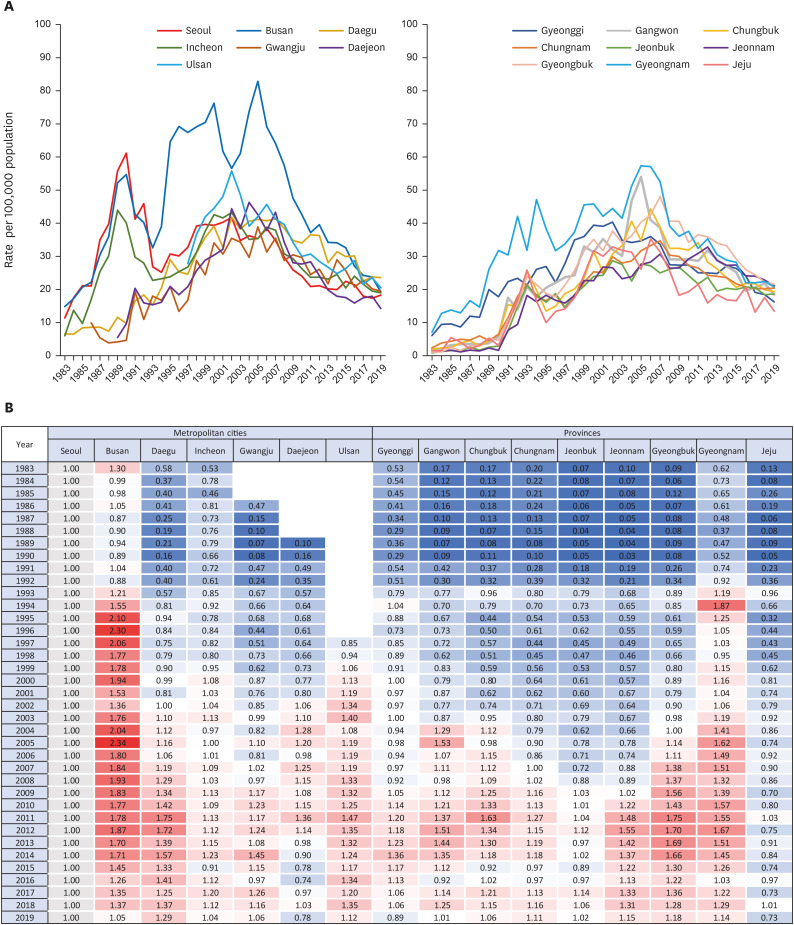

Despite remarkable reduction in cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, the burden has remained the leading cause of death. Since little research has focused on regional disparity in CVD mortality, this study aims to investigate its spatiotemporal trends in Korea from 1983 to 2019.

Methods

Using the causes of death statistics in Korea, we analyzed the geographic variation in deaths from CVDs from 1983 to 2019. The sex and age-standardized mortality rate was calculated according to the 17 administrative regions. The analyses include all diseases of the circulatory system (International Classification of Diseases-10 codes, I00–I99), along with the following 6 subcategories which were not mutually exclusive: total heart disease (I00–I13 and I20–I51), hypertensive heart disease (I10–I13), ischemic heart disease (I20–I25), myocardial infarction (I21–I23), heart failure (I50), and cerebrovascular disease (I60–I69).

Results

Overall, heart failure death rate increased across all regions, and other CVD death rates showed a decreasing trend. Regional disparity in mortality was substantial in the early 1980s but converged over time. In all types of cardiovascular mortality, Busan, Ulsan and Gyeongnam remained the highest, although they showed a downward trend like other regions. Jeju continued to have a relatively low CVD mortality rate.

Conclusions

The regional disparity substantially decreased compared to the 1980s. However, the relatively high burden of CVD mortality in the southeastern region has not been fully resolved.

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

What Regional Disparity Trends of Cardiovascular Mortality Have Changed in 2019 Compared to the 1980s?

Sung Il Im

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(11):844-846. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0276.Treatment Strategies of Improving Quality of Care in Patients With Heart Failure

Se-Eun Kim, Byung-Su Yoo

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(5):294-312. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0024.

Reference

-

1. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76:2982–3021. PMID: 33309175.2. Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation. 2015; 132:1667–1678. PMID: 26503749.

Article3. Paneni F, Diaz Cañestro C, Libby P, Lüscher TF, Camici GG. The aging cardiovascular system: understanding it at the cellular and clinical levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:1952–1967. PMID: 28408026.4. Seo E, Jung S, Lee H, Kim HC. Sex-specific trends in the prevalence of hypertension and the number of people with hypertension: analysis of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 1998-2018. Korean Circ J. 2022; 52:382–392. PMID: 35257521.

Article5. Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1333–1341. PMID: 25830423.

Article6. Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010; 35:72–115. PMID: 20109979.

Article7. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD compare: cardiovascular diseases [Internet]. Seattle (WA): IHME;2019. cited 2022 April 13. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/.8. Arafa A, Lee HH, Eshak ES, et al. Modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Korea and Japan. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:643–655. PMID: 34227266.

Article9. Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation. 2001; 104:2855–2864. PMID: 11733407.10. Roth GA, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, et al. Trends and patterns of geographic variation in cardiovascular mortality among US counties, 1980-2014. JAMA. 2017; 317:1976–1992. PMID: 28510678.

Article11. Wu Z, Yao C, Zhao D, et al. A collaborative study on trends and determinants in cardiovascular diseases in China, part I: morbidity and mortality monitoring. Circulation. 2001; 103:462–468. PMID: 11157701.12. Asaria P, Fortunato L, Fecht D, et al. Trends and inequalities in cardiovascular disease mortality across 7932 English electoral wards, 1982-2006: Bayesian spatial analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012; 41:1737–1749. PMID: 23129720.

Article13. Rodríguez Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillón P, Gutiérrez-Fisac JL, Ramón Banegas J, del Rey Calero J. Socioeconomic level, sedentary lifestyle, and wine consumption as possible explanations for geographic distribution of cerebrovascular disease mortality in Spain. Stroke. 1997; 28:922–928. PMID: 9158626.

Article14. Statistics Korea. Statistics Report on Cause of Death 2020. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2021.15. Baek J, Lee H, Lee HH, Heo JE, Cho SM, Kim HC. Thirty-six year trends in mortality from diseases of circulatory system in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:320–332. PMID: 33821581.

Article16. Lee J, Bahk J, Kim I, et al. Geographic variation in morbidity and mortality of cerebrovascular diseases in Korea during 2011-2015. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018; 27:747–757. PMID: 29128329.

Article17. Statistics Korea. Korea Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD) [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2022. cited 2022 April 18. Available from: http://kssc.kostat.go.kr/ksscNew_web/ekssc/main/main.do#.18. Lee H, Park S, Kim HC. Temporal and geospatial trends of hypertension management in Korea: a nationwide study 2002-2016. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:514–527. PMID: 30808085.

Article19. Sejong City Hall. History of Sejong [Internet]. Sejong: Sejong City Hall;2022. cited 2022 May 12. Available from: https://www.sejong.go.kr/eng/sub01_0201.do.20. Lee CY, Im EO. Socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular health in South Korea: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021; 36:8–22. PMID: 31851148.

Article21. Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, et al. A trend in epidemiology and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by urbanization level: a nationwide observational study from 2006 to 2010 in South Korea. Resuscitation. 2013; 84:547–557. PMID: 23313428.

Article22. Hong JS, Kang HC. Regional differences in treatment frequency and case-fatality rates in Korean patients with acute myocardial infarction using the Korea national health insurance claims database: findings of a large retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014; 93:e287. PMID: 25526465.23. Cho KH, Lee SG, Nam CM, et al. Disparities in socioeconomic status and neighborhood characteristics affect all-cause mortality in patients with newly diagnosed hypertension in Korea: a nationwide cohort study, 2002-2013. Int J Equity Health. 2016; 15:3. PMID: 26743664.

Article24. Shin J, Cho KH, Choi Y, Lee SG, Park EC, Jang SI. Combined effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on mortality in patients with newly diagnosed dyslipidemia: a nationwide Korean cohort study from 2002 to 2013. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016; 26:207–215. PMID: 26895648.

Article25. Park SY, Kwak JM, Seo EW, Lee KS. Spatial analysis of the regional variation of hypertensive disease mortality and its socio-economic correlates in South Korea. Geospat Health. 2016; 11:420. PMID: 27245801.

Article26. Gebreab SY, Davis SK, Symanzik J, Mensah GA, Gibbons GH, Diez-Roux AV. Geographic variations in cardiovascular health in the United States: contributions of state- and individual-level factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015; 4:e001673. PMID: 26019131.

Article27. Kang HJ, Kwon S. Regional disparity of cardiovascular mortality and its determinants. Health Policy Manag. 2016; 26:12–23.

Article28. Kim RB, Kim HS, Kang DR, et al. The trend in incidence and case-fatality of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction patients in Korea, 2007 to 2016. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34:e322. PMID: 31880418.

Article29. Sung KC. Trends in cardiovascular disease mortality: Can we prevent PRECISELY? Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:333–335. PMID: 33821582.

Article30. Won TY, Kang BS, Im TH, Choi HJ. The study of accuracy of death statistics. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2007; 18:256–262.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- What Regional Disparity Trends of Cardiovascular Mortality Have Changed in 2019 Compared to the 1980s?

- Trend of asthma prevalence among children based on regional urbanization level in Japan; 2006–2019

- Regional Disparity of Cardiovascular Mortality and Its Determinants

- Trends and disparities in avoidable, treatable, and preventable mortalities in South Korea, 2001-2020: comparison of capital and non-capital areas

- Causes of Child Mortality (1 to 4 Years of Age) From 1983 to 2012 in the Republic of Korea: National Vital Data