Korean J Transplant.

2022 Jun;36(2):127-135. 10.4285/kjt.22.0017.

Living donor liver transplant outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: does a decrease in case volume impact the overall outcomes?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anaesthesiology and Critical Care, Center for Liver and Biliary Sciences, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India

- 2Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Center for Liver and Biliary Sciences, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India

- 3Department of Hepatobiliary, Pancreatic Surgery and Liver Transplant, Center for Liver and Biliary Sciences, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India

- 4Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Center for Liver and Biliary Sciences, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India

- KMID: 2531136

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/kjt.22.0017

Abstract

- Background

High-volume centers (HVCs) are classically associated with better out- comes. During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been a decrease in the regular liver transplantation (LT) activity at our center. This study ana- lyzed the effect of the decline in LT on posttransplant patient outcomes at our HVC.

Methods

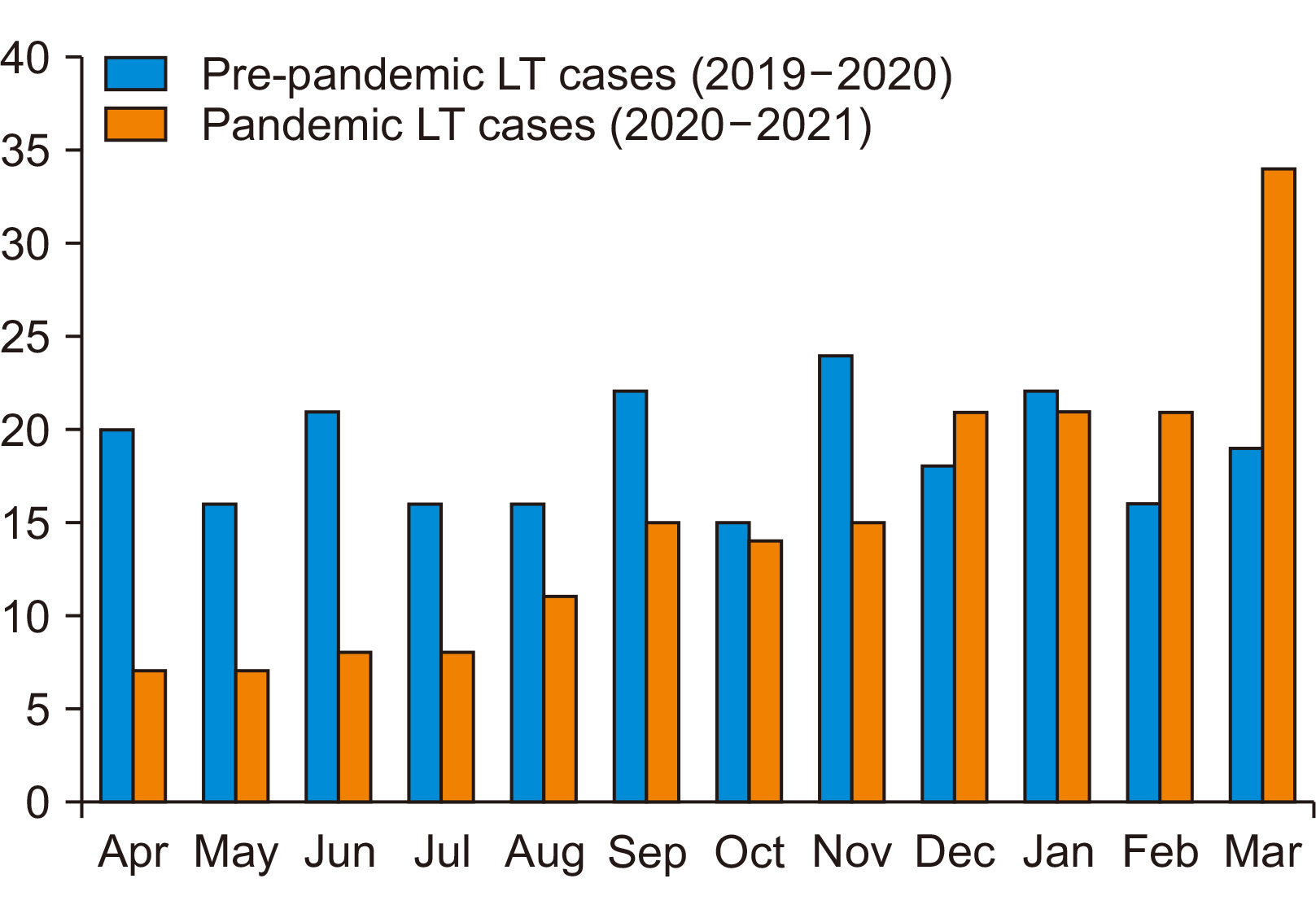

We compared the surgical outcomes of patients who underwent LT during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (April 1, 2020 to September 30, 2020) with outcomes in the pre-pandemic calendar year (April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020).

Results

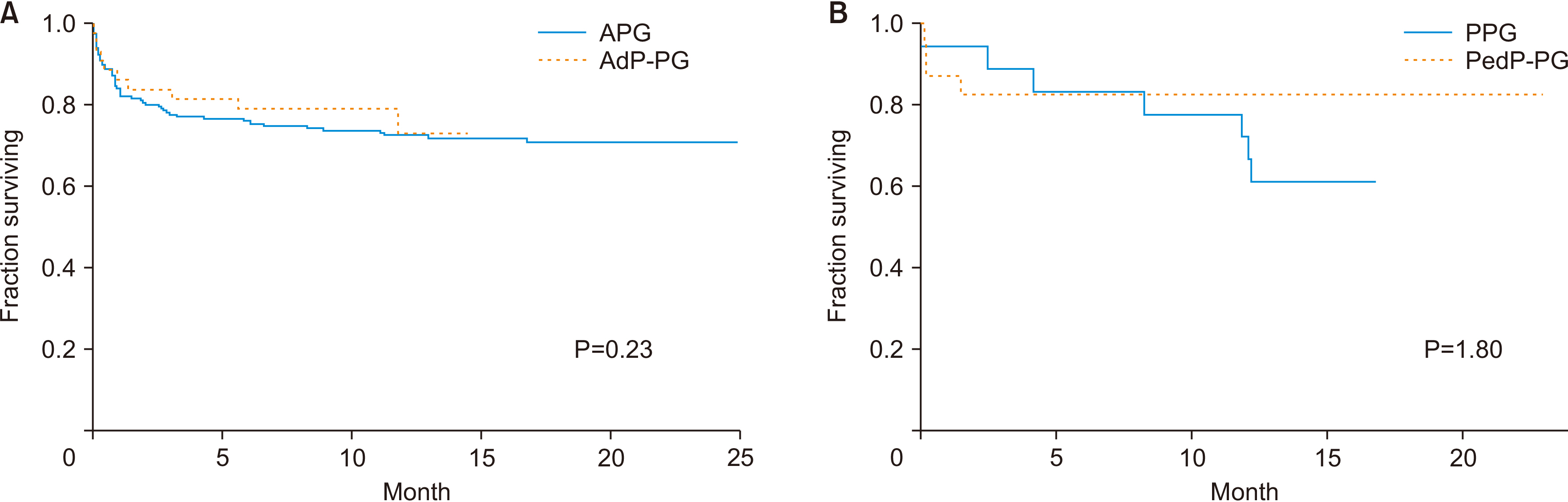

During the 6 months of pandemic lockdown, 60 patients underwent LT (43 adults and 17 children) while 228 patients underwent LT (178 adults and 50 children) during the pre-pandemic calendar year. Patients in the pandemic group had significant- ly higher model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores (24.39±9.55 vs. 21.14±9.17, P=0.034), Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores (11.46±2.32 vs. 10.25±2.24, P=0.03), and inci-dence of acute-on-chronic liver failure (30.2% vs. 10.2%, P=0.002). Despite performing LT in sicker patients with COVID-19-related challenges, the 30-day (14% vs. 18.5%, P=0.479), 3-month (16.3% vs. 20.2%, P=0.557), and 6-month mortality rates (23.3% vs. 28.7%, P=0.477) were lower, but not statistically significant when compared to the pre-pandemic cohort.

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown the number of LT procedures performed at our HVC declined by half because prevailing conditions allowed LT in very sick patients only. Despite these changes, outcomes were not inferior during the pan- demic period compared to the pre-pandemic calendar year. Greater individualization of patient care contributed to non-inferior outcomes in these sick recipients.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hsieh CE, Hsu YL, Lin KH, Lin PY, Hung YJ, Lai YC, et al. 2021; Association between surgical volumes and hospital mortality in patients: a living donor liver transplantation single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 21:228. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-021-01732-6. PMID: 34016057. PMCID: PMC8136228.2. Modi RM, Tumin D, Kruger AJ, Beal EW, Hayes D Jr, Hanje J, et al. 2018; Effect of transplant center volume on post-transplant survival in patients listed for simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation. World J Hepatol. 10:134–41. DOI: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i1.134. PMID: 29399287. PMCID: PMC5787677.3. Hata T, Motoi F, Ishida M, Naitoh T, Katayose Y, Egawa S, et al. 2016; Effect of hospital volume on surgical outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 263:664–72. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001437. PMID: 26636243.4. Northup PG, Pruett TL, Stukenborg GJ, Berg CL. 2006; Survival after adult liver transplantation does not correlate with transplant center case volume in the MELD era. Am J Transplant. 6:2455–62. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01501.x. PMID: 16925567.5. Yoo S, Jang EJ, Yi NJ, Kim GH, Kim DH, Lee H, et al. 2019; Effect of institutional case volume on in-hospital mortality after living donor liver transplantation: analysis of 7073 cases between 2007 and 2016 in Korea. Transplantation. 103:952–8. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002394. PMID: 30086090.6. Axelrod DA, Guidinger MK, McCullough KP, Leichtman AB, Punch JD, Merion RM. 2004; Association of center volume with outcome after liver and kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 4:920–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00462.x. PMID: 15147426.7. Narasimhan G. 2016; Living donor liver transplantation in India. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 5:127–32. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2015.09.01. PMID: 27115006. PMCID: PMC4824736.8. Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P. EASL-CLIF Consortium CANONIC Study. 2015; Acute-on-chronic liver failure: a new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 62(1 Suppl):S131–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.045. PMID: 25920082.9. Tracy ET, Bennett KM, Danko ME, Diesen DL, Westmoreland TJ, Kuo PC, et al. 2010; Low volume is associated with worse patient outcomes for pediatric liver transplant centers. J Pediatr Surg. 45:108–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.10.018. PMID: 20105589.10. Ozhathil DK, Li Y, Smith JK, Tseng JF, Saidi RF, Bozorgzadeh A, et al. 2011; Effect of centre volume and high donor risk index on liver allograft survival. HPB (Oxford). 13:447–53. DOI: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00320.x. PMID: 21689227. PMCID: PMC3133710.11. Guba M. 2014; Center volume, competition, and outcome in German liver transplant centers. Transplant Res. 3:6. DOI: 10.1186/2047-1440-3-6. PMID: 24513092. PMCID: PMC3929147.12. Macomber CW, Shaw JJ, Santry H, Saidi RF, Jabbour N, Tseng JF, et al. 2012; Centre volume and resource consumption in liver transplantation. HPB (Oxford). 14:554–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00503.x. PMID: 22762404. PMCID: PMC3406353.13. Oh SY, Jang EJ, Kim GH, Lee H, Yi NJ, Yoo S, et al. 2021; Association between hospital liver transplantation volume and mortality after liver re-transplantation. PLoS One. 16:e0255655. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255655. PMID: 34351979. PMCID: PMC8341477.14. Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). 2020. Guidelines for liver transplantation and COVID-19 infection [Internet]. New Delhi;Available from: https://www.icmr.gov.in/ctechdocad.html. cited 2022 Mar 30.15. Saigal S, Gupta S, Sudhindran S, Goyal N, Rastogi A, Jacob M, et al. 2020; Liver transplantation and COVID-19 (Coronavirus) infection: guidelines of the Liver Transplant Society of India (LTSI). Hepatol Int. 14:429–31. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-020-10041-1. PMID: 32270388. PMCID: PMC7140588.16. Delman AM, Turner KM, Jones CR, Vaysburg DM, Silski LS, King C, et al. 2021; Keeping the lights on: telehealth, testing, and 6-month outcomes for orthotopic liver transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surgery. 169:1519–24. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.12.044. PMID: 33589248. PMCID: PMC7833561.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of kidney transplant outcomes before and after COVID-19 pandemic: a single-institution experience

- Patient and graft outcome of kidney transplantation during COVID-19 pandemic: a single center experience

- Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cardiac Surgery Practice and Outcomes

- Insights and pearls of healthcare systems management of COVID-19 in Asia and its relevance to Asian transplant services

- Back on track: outcomes of deceased donor kidney recipients at national kidney and transplant institute during the COVID-19 pandemic