J Rheum Dis.

2022 Jul;29(3):140-153. 10.4078/jrd.2022.29.3.140.

The Mechanism of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pathogenic Implication in the Pathogenesis of Gout

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2530678

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2022.29.3.140

Abstract

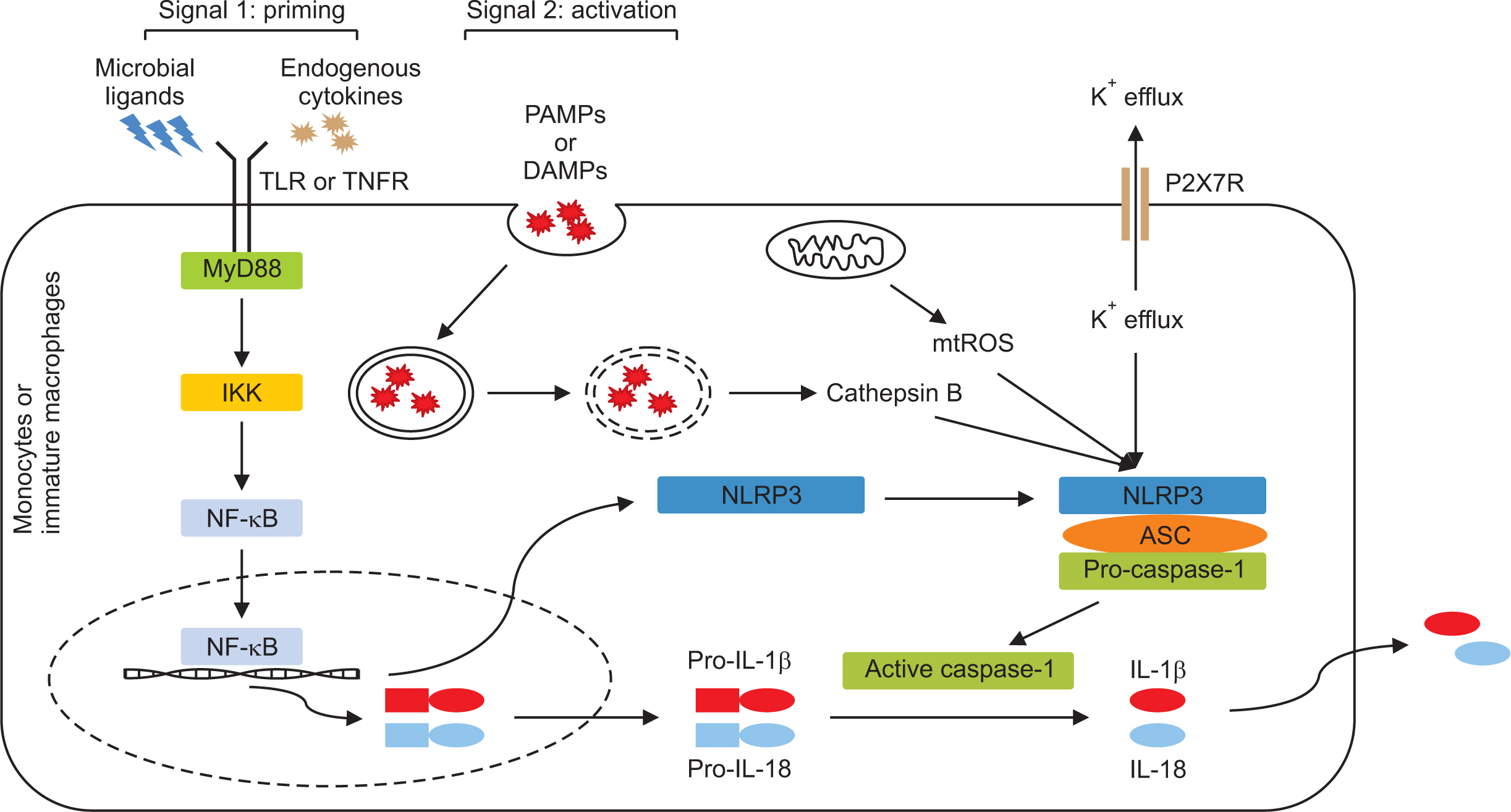

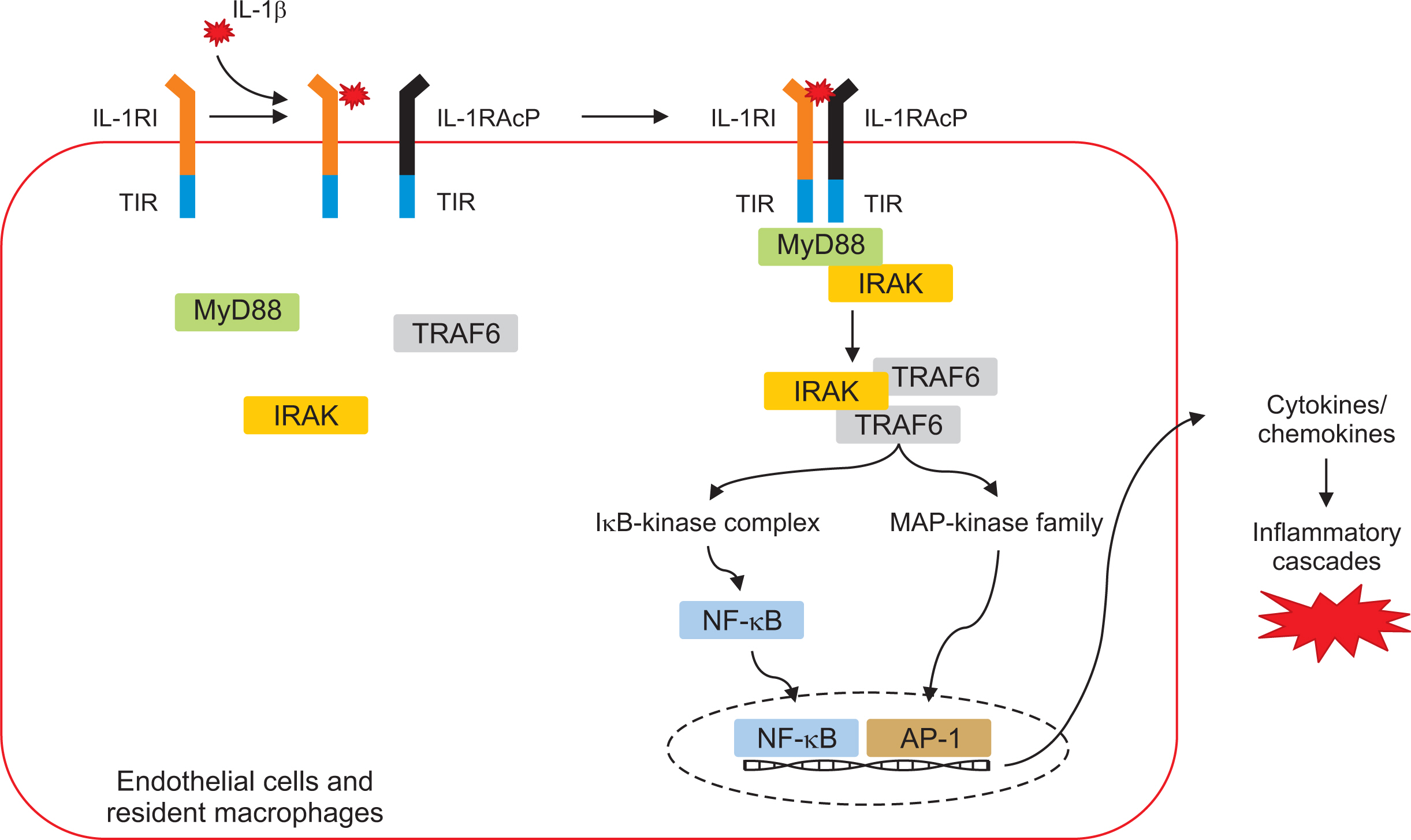

- The NACHT, LRR, and PYD-domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is an intracellular multi-protein signaling platform that is activated by cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors such as NLRs against endogenous and exogenous pathogens. Once it is activated by a variety of danger signals, recruitment and assembly of NLRP3, ASC, and pro-caspase-1 trigger the processing and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18. Multiple intracellular and extracellular structures and molecular mechanisms are involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Gout is an autoinflammatory disease induced by inflammatory response through production of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β by deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in the articular joints and periarticular structures. NLRP3 inflammasome is considered a main therapeutic target in MSU crystal-induced inflammation in gout. Novel therapeutic strategies have been proposed to control acute flares of gouty arthritis and prophylaxis for gout flares through modulation of the NLRP3/IL-1 axis pathway. This review discusses the basic mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and the IL-1-induced inflammatory cascade and explains the NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pathogenic role in the pathogenesis of gout.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Dalbeth N, Gosling AL, Gaffo A, Abhishek A. 2021; Gout. Lancet. 397:1843–55. Erratum in: Lancet 2021;397:1808. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00569-9.

Article2. Busso N, So A. 2010; Mechanisms of inflammation in gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 12:206. DOI: 10.1186/ar2952. PMID: 20441605. PMCID: PMC2888190.

Article3. Nuki G, Simkin PA. 2006; A concise history of gout and hyperuricemia and their treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 8(Suppl 1):S1. DOI: 10.1186/ar1906. PMID: 16820040. PMCID: PMC3226106.4. Freudweiler M. 1899; Experimentelle untersuchungen uber das wesen der gichtknoten. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 63:266–335. German.5. McCarty DJ, Hollander JL. 1961; Identification of urate crystals in gouty synovial fluid. Ann Intern Med. 54:452–60. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-54-3-452. PMID: 13773775.

Article6. Scanu A, Oliviero F, Ramonda R, Frallonardo P, Dayer JM, Punzi L. 2012; Cytokine levels in human synovial fluid during the different stages of acute gout: role of transforming growth factor β1 in the resolution phase. Ann Rheum Dis. 71:621–4. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200711. PMID: 22294622.

Article7. Rock KL, Kataoka H, Lai JJ. 2013; Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 9:13–23. DOI: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.143. PMID: 22945591. PMCID: PMC3648987.

Article8. Jo EK, Kim JK, Shin DM, Sasakawa C. 2016; Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 13:148–59. DOI: 10.1038/cmi.2015.95. PMID: 26549800. PMCID: PMC4786634.

Article9. Kingsbury SR, Conaghan PG, McDermott MF. 2011; The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in gout. J Inflamm Res. 4:39–49. DOI: 10.2147/JIR.S11330. PMID: 22096368. PMCID: PMC3218743.10. Paludan SR, Pradeu T, Masters SL, Mogensen TH. 2021; Constitutive immune mechanisms: mediators of host defence and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 21:137–50. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-020-0391-5. PMID: 32782357. PMCID: PMC7418297.

Article11. Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. 2009; The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 27:229–65. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. PMID: 19302040.

Article12. Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. 2002; The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 10:417–26. DOI: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3.13. Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, et al. 2009; Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 183:787–91. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. PMID: 19570822. PMCID: PMC2824855.

Article14. McGeough MD, Wree A, Inzaugarat ME, Haimovich A, Johnson CD, Peña CA, et al. 2017; TNF regulates transcription of NLRP3 inflammasome components and inflammatory molecules in cryopyrinopathies. J Clin Invest. 127:4488–97. DOI: 10.1172/JCI90699. PMID: 29130929. PMCID: PMC5707143.

Article15. Schroder K, Sagulenko V, Zamoshnikova A, Richards AA, Cridland JA, Irvine KM, et al. 2012; Acute lipopolysaccharide priming boosts inflammasome activation independently of inflammasome sensor induction. Immunobiology. 217:1325–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.07.020. PMID: 22898390.

Article16. Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Núñez G. 2009; Cutting edge: TNF-alpha mediates sensitization to ATP and silica via the NLRP3 inflammasome in the absence of microbial stimulation. J Immunol. 183:792–6. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900173. PMID: 19542372. PMCID: PMC2754237.

Article17. Groslambert M, Py BF. 2018; Spotlight on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. J Inflamm Res. 11:359–74. DOI: 10.2147/JIR.S141220. PMID: 30288079. PMCID: PMC6161739.

Article18. Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, et al. 2014; FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. J Immunol. 192:1835–46. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302839. PMID: 24453255. PMCID: PMC3933570.

Article19. Bauernfeind F, Bartok E, Rieger A, Franchi L, Núñez G, Hornung V. 2011; Cutting edge: reactive oxygen species inhibitors block priming, but not activation, of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 187:613–7. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100613. PMID: 21677136. PMCID: PMC3131480.

Article20. Juliana C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Kang S, Farias A, Qin F, Alnemri ES. 2012; Non-transcriptional priming and deubiquitination regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Biol Chem. 287:36617–22. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407130. PMID: 22948162. PMCID: PMC3476327.

Article21. Lin KM, Hu W, Troutman TD, Jennings M, Brewer T, Li X, et al. 2014; IRAK-1 bypasses priming and directly links TLRs to rapid NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111:775–80. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:3195. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1320294111. PMID: 24379360. PMCID: PMC3896167.

Article22. Cookson BT, Brennan MA. 2001; Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol. 9:113–4. DOI: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01936-3.

Article23. Laudisi F, Spreafico R, Evrard M, Hughes TR, Mandriani B, Kandasamy M, et al. 2013; Cutting edge: the NLRP3 inflammasome links complement-mediated inflammation and IL-1β release. J Immunol. 191:1006–1. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300489. PMID: 23817414. PMCID: PMC3718202.

Article24. Solle M, Labasi J, Perregaux DG, Stam E, Petrushova N, Koller BH, et al. 2001; Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X(7) receptors. J Biol Chem. 276:125–32. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M006781200. PMID: 11016935.25. Dostert C, Pétrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. 2008; Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 320:674–7. DOI: 10.1126/science.1156995. PMID: 18403674. PMCID: PMC2396588.

Article26. Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. 2006; Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 440:237–41. DOI: 10.1038/nature04516. PMID: 16407889.

Article27. Perregaux D, Gabel CA. 1994; Interleukin-1 beta maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J Biol Chem. 269:15195–203. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)36591-2.

Article28. Kahlenberg JM, Dubyak GR. 2004; Mechanisms of caspase-1 activation by P2X7 receptor-mediated K+ release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 286:C1100–8. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2003. PMID: 15075209.29. Pétrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. 2007; Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 14:1583–9. DOI: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. PMID: 17599094.

Article30. Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. 2006; Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 25:5071–82. DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. PMID: 17036048. PMCID: PMC1630421.

Article31. Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Adinolfi E, Lemoli RM, Curti A, Idzko M, et al. 2006; The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol. 176:3877–83. Erratum in: J Immunol 2007;179:8569. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3877. PMID: 16547218.

Article32. Greaney AJ, Leppla SH, Moayeri M. 2015; Bacterial exotoxins and the inflammasome. Front Immunol. 6:570. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00570. PMID: 26617605. PMCID: PMC4639612.

Article33. Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G. 2013; K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 38:1142–53. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. PMID: 23809161. PMCID: PMC3730833.

Article34. Lee GS, Subramanian N, Kim AI, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, Sacks DB, et al. 2012; The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature. 492:123–7. DOI: 10.1038/nature11588. PMID: 23143333. PMCID: PMC4175565.

Article35. Murakami T, Ockinger J, Yu J, Byles V, McColl A, Hofer AM, et al. 2012; Critical role for calcium mobilization in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109:11282–7. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1117765109. PMID: 22733741. PMCID: PMC3396518.

Article36. Duchen MR. 2000; Mitochondria and calcium: from cell signalling to cell death. J Physiol. 529:57–68. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00057.x. PMID: 11080251. PMCID: PMC2270168.

Article37. Camello-Almaraz C, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Pozo MJ, Camello PJ. 2006; Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 291:C1082–8. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00217.2006. PMID: 16760264.38. Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, et al. 2008; The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 9:857–65. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1636. PMID: 18604209. PMCID: PMC3101478.

Article39. Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, et al. 2008; Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 9:847–56. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1631. PMID: 18604214. PMCID: PMC2834784.

Article40. Orlowski GM, Colbert JD, Sharma S, Bogyo M, Robertson SA, Rock KL. 2015; Multiple cathepsins promote pro-IL-1β synthesis and NLRP3-mediated IL-1β activation. J Immunol. 195:1685–97. Erratum in: J Immunol 2016;196:503. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500509. PMID: 26195813. PMCID: PMC4530060.

Article41. Barlan AU, Griffin TM, McGuire KA, Wiethoff CM. 2011; Adenovirus membrane penetration activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Virol. 85:146–55. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01265-10. PMID: 20980503. PMCID: PMC3014182.

Article42. Gupta R, Ghosh S, Monks B, DeOliveira RB, Tzeng TC, Kalantari P, et al. 2014; RNA and β-hemolysin of group B Streptococcus induce interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by activating NLRP3 inflammasomes in mouse macrophages. J Biol Chem. 289:13701–5. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.C114.548982. PMID: 24692555. PMCID: PMC4022842.

Article43. Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. 2011; A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 469:221–5. Erratum in: Nature 2011;475:122. DOI: 10.1038/nature09663. PMID: 21124315.

Article44. Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, et al. 2011; Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 12:222–30. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1980. PMID: 21151103. PMCID: PMC3079381.

Article45. Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Dagvadorj J, Chiba N, Chen S, et al. 2012; Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity. 36:401–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.009. PMID: 22342844. PMCID: PMC3312986.

Article46. Saïd-Sadier N, Padilla E, Langsley G, Ojcius DM. 2010; Aspergillus fumigatus stimulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through a pathway requiring ROS production and the Syk tyrosine kinase. PLoS One. 5:e10008. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010008. PMID: 20368800. PMCID: PMC2848854.

Article47. Pietrella D, Pandey N, Gabrielli E, Pericolini E, Perito S, Kasper L, et al. 2013; Secreted aspartic proteases of Candida albicans activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol. 43:679–92. DOI: 10.1002/eji.201242691. PMID: 23280543.48. Shi H, Wang Y, Li X, Zhan X, Tang M, Fina M, et al. 2016; NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component. Nat Immunol. 17:250–8. DOI: 10.1038/ni.3333. PMID: 26642356. PMCID: PMC4862588.

Article49. He Y, Zeng MY, Yang D, Motro B, Núñez G. 2016; NEK7 is an essential mediator of NLRP3 activation downstream of potassium efflux. Nature. 530:354–7. DOI: 10.1038/nature16959. PMID: 26814970. PMCID: PMC4810788.

Article50. Junn E, Han SH, Im JY, Yang Y, Cho EW, Um HD, et al. 2000; Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 mediates oxidative stress via suppressing the thioredoxin function. J Immunol. 164:6287–95. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6287. PMID: 10843682.

Article51. Nishiyama A, Matsui M, Iwata S, Hirota K, Masutani H, Nakamura H, et al. 1999; Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3) up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J Biol Chem. 274:21645–50. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21645. PMID: 10419473.

Article52. Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. 2010; Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 11:136–40. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1831. PMID: 20023662.

Article53. Medzhitov R, Janeway C Jr. 2000; Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev. 173:89–97. DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.917309.x. PMID: 10719670.

Article54. Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL. 2003; Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature. 425:516–21. DOI: 10.1038/nature01991. PMID: 14520412.

Article55. Kippen I, Klinenberg JR, Weinberger A, Wilcox WR. 1974; Factors affecting urate solubility in vitro. Ann Rheum Dis. 33:313–7. DOI: 10.1136/ard.33.4.313. PMID: 4413418. PMCID: PMC1006264.

Article56. Yagnik DR, Hillyer P, Marshall D, Smythe CD, Krausz T, Haskard DO, et al. 2000; Noninflammatory phagocytosis of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals by mouse macrophages. Implications for the control of joint inflammation in gout. Arthritis Rheum. 43:1779–89. DOI: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1779::AID-ANR14>3.0.CO;2-2.

Article57. Landis RC, Yagnik DR, Florey O, Philippidis P, Emons V, Mason JC, et al. 2002; Safe disposal of inflammatory monosodium urate monohydrate crystals by differentiated macrophages. Arthritis Rheum. 46:3026–33. DOI: 10.1002/art.10614. PMID: 12428246.

Article58. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Mouktaroudi M, Bodar E, van der Ven J, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG, et al. 2009; Crystals of monosodium urate monohydrate enhance lipopolysaccharide-induced release of interleukin 1 beta by mononuclear cells through a caspase 1-mediated process. Ann Rheum Dis. 68:273–8. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2007.082222. PMID: 18390571.59. Liu-Bryan R, Scott P, Sydlaske A, Rose DM, Terkeltaub R. 2005; Innate immunity conferred by Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 expression is pivotal to monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 52:2936–46. DOI: 10.1002/art.21238. PMID: 16142712.

Article60. Chen CJ, Shi Y, Hearn A, Fitzgerald K, Golenbock D, Reed G, et al. 2006; MyD88-dependent IL-1 receptor signaling is essential for gouty inflammation stimulated by monosodium urate crystals. J Clin Invest. 116:2262–71. DOI: 10.1172/JCI28075. PMID: 16886064. PMCID: PMC1523415.

Article61. Scott P, Ma H, Viriyakosol S, Terkeltaub R, Liu-Bryan R. 2006; Engagement of CD14 mediates the inflammatory potential of monosodium urate crystals. J Immunol. 177:6370–8. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6370. PMID: 17056568.

Article62. Holzinger D, Nippe N, Vogl T, Marketon K, Mysore V, Weinhage T, et al. 2014; Myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 contribute to monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced inflammation in gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66:1327–39. DOI: 10.1002/art.38369. PMID: 24470119.

Article63. So AK, Martinon F. 2017; Inflammation in gout: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 13:639–47. DOI: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.155. PMID: 28959043.

Article64. Kim SK, Choe JY, Park KY. 2019; Anti-inflammatory effect of artemisinin on uric acid-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation through blocking interaction between NLRP3 and NEK7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 517:338–45. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.087. PMID: 31358323.

Article65. Kim SK, Choe JY, Park KY. 2019; TXNIP-mediated nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway and intracellular shifting of TXNIP in uric acid-induced NLRP3 inflammasome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 511:725–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.141. PMID: 30833078.

Article66. Fields JK, Günther S, Sundberg EJ. 2019; Structural basis of IL-1 family cytokine signaling. Front Immunol. 10:1412. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01412. PMID: 31281320. PMCID: PMC6596353.

Article67. Kaneko N, Kurata M, Yamamoto T, Morikawa S, Masumoto J. 2019; The role of interleukin-1 in general pathology. Inflamm Regen. 39:12. DOI: 10.1186/s41232-019-0101-5. PMID: 31182982. PMCID: PMC6551897.

Article68. Dinarello CA. 2011; Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood. 117:3720–32. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-273417. PMID: 21304099. PMCID: PMC3083294.

Article69. Mariotte A, De Cauwer A, Po C, Abou-Faycal C, Pichot A, Paul N, et al. 2020; A mouse model of MSU-induced acute inflammation in vivo suggests imiquimod-dependent targeting of Il-1β as relevant therapy for gout patients. Theranostics. 10:2158–71. DOI: 10.7150/thno.40650. PMID: 32104502. PMCID: PMC7019178.

Article70. Netea MG, van de Veerdonk FL, van der Meer JW, Dinarello CA, Joosten LA. 2015; Inflammasome-independent regulation of IL-1-family cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 33:49–77. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112306. PMID: 25493334.

Article71. Guma M, Ronacher L, Liu-Bryan R, Takai S, Karin M, Corr M. 2009; Caspase 1-independent activation of interleukin-1beta in neutrophil-predominant inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 60:3642–50. DOI: 10.1002/art.24959. PMID: 19950258. PMCID: PMC2847793.

Article72. Joosten LA, Crişan TO, Azam T, Cleophas MC, Koenders MI, van de Veerdonk FL, et al. 2016; Alpha-1-anti-trypsin-Fc fusion protein ameliorates gouty arthritis by reducing release and extracellular processing of IL-1β and by the induction of endogenous IL-1Ra. Ann Rheum Dis. 75:1219–27. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206966. PMID: 26174021.

Article73. FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt G, Abeles AM, et al. 2020; 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. 72:879–95. Erratum in: Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:413. DOI: 10.1002/art.41688. PMID: 33638303.

Article74. Wannamaker W, Davies R, Namchuk M, Pollard J, Ford P, Ku G, et al. 2007; (S)-1-((S)-2-{[1-(4-amino-3-chloro-phenyl)-methanoyl]-amino}-3,3-dimethyl-butanoyl)-pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid ((2R,3S)-2-ethoxy-5-oxo-tetrahydro-furan-3-yl)-amide (VX-765), an orally available selective interleukin (IL)-converting enzyme/caspase-1 inhibitor, exhibits potent anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting the release of IL-1beta and IL-18. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 321:509–16. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.106.111344. PMID: 17289835.

Article75. Zhang Y, Zheng Y. 2016; Effects and mechanisms of potent caspase-1 inhibitor VX765 treatment on collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 34:111–8.76. Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Muñoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, et al. 2015; A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 21:248–55. DOI: 10.1038/nm.3806. PMID: 25686105. PMCID: PMC4392179.

Article77. Jiang H, He H, Chen Y, Huang W, Cheng J, Ye J, et al. 2017; Identification of a selective and direct NLRP3 inhibitor to treat inflammatory disorders. J Exp Med. 214:3219–38. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20171419. PMID: 29021150. PMCID: PMC5679172.

Article78. Huang Y, Jiang H, Chen Y, Wang X, Yang Y, Tao J, et al. 2018; Tranilast directly targets NLRP3 to treat inflammasome-driven diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 10:e8689. DOI: 10.15252/emmm.201708689.

Article79. Kim SK, Choe JY, Park KY. 2016; Rebamipide suppresses monosodium urate crystal-induced interleukin-1β production through regulation of oxidative stress and caspase-1 in THP-1 cells. Inflammation. 39:473–82. DOI: 10.1007/s10753-015-0271-5. PMID: 26454448.

Article80. So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. 2007; A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 9:R28. DOI: 10.1186/ar2143. PMID: 17352828. PMCID: PMC1906806.

Article81. Ghosh P, Cho M, Rawat G, Simkin PA, Gardner GC. 2013; Treatment of acute gouty arthritis in complex hospitalized patients with anakinra. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 65:1381–4. DOI: 10.1002/acr.21989. PMID: 23650178.

Article82. Ottaviani S, Moltó A, Ea HK, Neveu S, Gill G, Brunier L, et al. 2013; Efficacy of anakinra in gouty arthritis: a retrospective study of 40 cases. Arthritis Res Ther. 15:R123. DOI: 10.1186/ar4303. PMID: 24432362. PMCID: PMC3978950.

Article83. Schlesinger N, Alten RE, Bardin T, Schumacher HR, Bloch M, Gimona A, et al. 2012; Canakinumab for acute gouty arthritis in patients with limited treatment options: results from two randomised, multicentre, active-controlled, double-blind trials and their initial extensions. Ann Rheum Dis. 71:1839–48. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200908. PMID: 22586173.

Article84. Schlesinger N, Mysler E, Lin HY, De Meulemeester M, Rovensky J, Arulmani U, et al. 2011; Canakinumab reduces the risk of acute gouty arthritis flares during initiation of allopurinol treatment: results of a double-blind, randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 70:1264–71. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2010.144063. PMID: 21540198. PMCID: PMC3103669.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- NLRP3 Inflammasome and Host Protection against Bacterial Infection

- The Role of NLR-related Protein 3 Inflammasome in Host Defense and Inflammatory Diseases

- Loganin Prevents Hepatic Steatosis by Blocking NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

- Resistance to Chemotherapy on Tumor Through Cathepsin B-dependent Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome

- Ethanol Augments Monosodium Urate-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation via Regulation of AhR and TXNIP in Human Macrophages