J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Apr;37(14):e117. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e117.

The Effectiveness and Harms of Screening for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Public Health Science, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Gachon Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, College of Pharmacy, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 5College of Medicine, Inha University, Incheon, Korea

- KMID: 2528145

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e117

Abstract

- Background

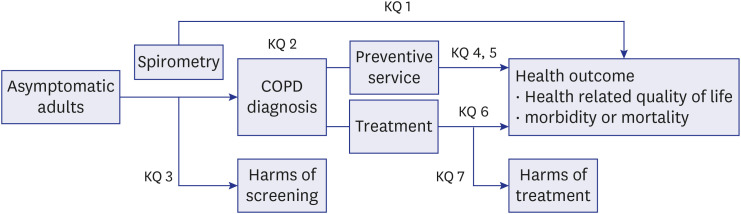

This study aimed to perform meta-analyses to update a previous systematic review (SR) conducted by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to evaluate the benefits and harms of screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in asymptomatic adults.

Methods

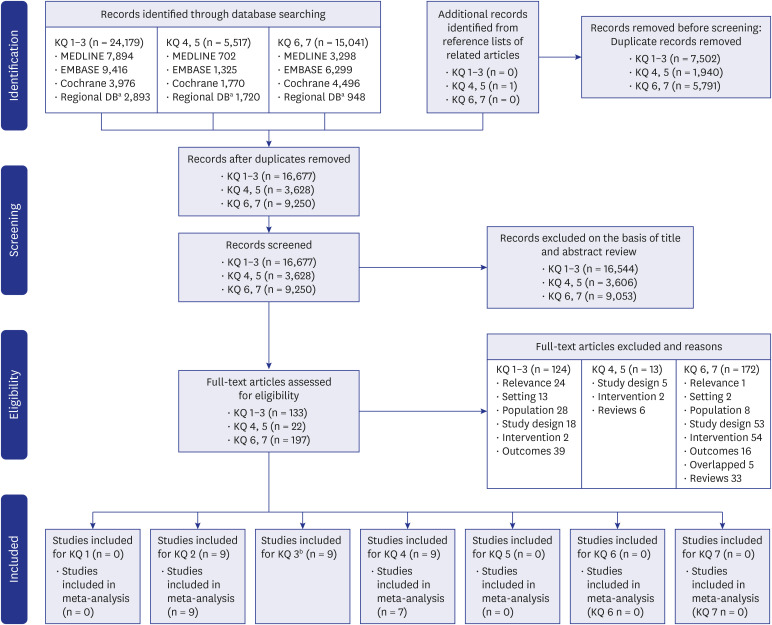

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and regional databases were searched from their inception to January 2020. Studies for diagnostic accuracy, preventive services effect, treatment efficacy, and treatment harms were included.

Results

Eighteen studies were included, and twelve of these were newly added in this update. In meta-analyses, the pooled sensitivity and specificity for COPD diagnosis using spirometry were 73.4% and 89.0%, respectively. The relative effect of smoking cessation intervention with screening spirometry, presented as abstinence rate, was not statistically significant (risk ratio [RR], 1.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.67) when all selected studies were pooled, but screening on smoking cessation was effective (RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.14–2.19) when limited to studies with smoking cessation programs that provided smoking cessation medicines or intensive counseling at public health centers or medical institutions.

Conclusion

In this study, no direct evidence for the impact on health outcomes of screening asymptomatic adults for COPD was identified similar to the previous SR. Further research is necessary to confirm the benefits of COPD screening.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Soriano JB, Kendrick PJ, Paulson KR, Gupta V, Abrams EM, Adedoyin RA, et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8(6):585–596. PMID: 32526187.2. Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396(10258):1204–1222. PMID: 33069326.3. Kim YE, Park H, Jo MW, Oh IH, Go DS, Jung J, et al. Trends and patterns of burden of disease and injuries in Korea using disability-adjusted life years. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(Suppl 1):e75. PMID: 30923488.

Article4. Park SC, Kim DW, Park EC, Shin CS, Rhee CK, Kang YA, et al. Mortality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Korean J Intern Med. 2019; 34(6):1272–1278. PMID: 31610634.

Article5. Lamprecht B, Soriano JB, Studnicka M, Kaiser B, Vanfleteren LE, Gnatiuc L, et al. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest. 2015; 148(4):971–985. PMID: 25950276.

Article6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2021 report. Updated November 2020. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf .7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management NICE guideline [NG115]. Updated December 5, 2018. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115/resources/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-in-over-16s-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66141600098245 .8. Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, García FA, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016; 315(13):1372–1377. PMID: 27046365.9. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, Hanania NA, Criner G, van der Molen T, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011; 155(3):179–191. PMID: 21810710.

Article10. Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, Mularski RA, Whitlock EP. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2016; 315(13):1378–1393. PMID: 27046366.

Article11. Boehm A, Pizzini A, Sonnweber T, Loeffler-Ragg J, Lamina C, Weiss G, et al. Assessing global COPD awareness with Google Trends. Eur Respir J. 2019; 53(6):1900351. PMID: 31097517.

Article12. Freeman D, Price D. ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Primary care and palliative care. BMJ. 2006; 333(7560):188–190. PMID: 16858049.13. Martinez CH, Mannino DM, Jaimes FA, Curtis JL, Han MK, Hansel NN, et al. Undiagnosed obstructive lung disease in the United States. Associated factors and long-term mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015; 12(12):1788–1795. PMID: 26524488.

Article14. Ford ES, Mannino DM, Wheaton AG, Presley-Cantrell L, Liu Y, Giles WH, et al. Trends in the use, sociodemographic correlates, and undertreatment of prescription medications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United States from 1999 to 2010. PLoS One. 2014; 9(4):e95305. PMID: 24751857.

Article15. Hwang YI, Park YB, Yoo KH. Recent trends in the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2017; 80(3):226–229. PMID: 28747954.

Article16. Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. COPD clinical practice guideline revised 2018. Updated February 8, 2018. Accessed February 5, 2022. https://www.lungkorea.org/bbs/index.html?code=guide&category=&gubun=&page=1&number=8186&mode=view&keyfield=&key= .17. McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (2):CD003793. PMID: 25705944.

Article18. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011; 155(8):529–536. PMID: 22007046.

Article19. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011; 343:d5928. PMID: 22008217.

Article20. Prentice HA, Mannino DM, Caldwell GG, Bush HM. Significant bronchodilator responsiveness and “reversibility” in a population sample. COPD. 2010; 7(5):323–330. PMID: 20854046.

Article21. Schermer TR, Smeele IJ, Thoonen BP, Lucas AE, Grootens JG, van Boxem TJ, et al. Current clinical guideline definitions of airflow obstruction and COPD overdiagnosis in primary care. Eur Respir J. 2008; 32(4):945–952. PMID: 18550607.

Article22. Ching SM, Pang YK, Price D, Cheong AT, Lee PY, Irmi I, et al. Detection of airflow limitation using a handheld spirometer in a primary care setting. Respirology. 2014; 19(5):689–693. PMID: 24708063.

Article23. Frith P, Crockett A, Beilby J, Marshall D, Attewell R, Ratnanesan A, et al. Simplified COPD screening: validation of the PiKo-6® in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2011; 20(2):190–198. PMID: 21597667.

Article24. Kobayashi S, Hanagama M, Yanai M. Ishinomaki COPD Network (ICON) Investigators. Early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. Intern Med. 2017; 56(23):3153–3158. PMID: 28943559.

Article25. Labor M, Vrbica Ž, Gudelj I, Labor S, Plavec D. Diagnostic accuracy of a pocket screening spirometer in diagnosing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice: a cross sectional validation study using tertiary care as a reference. BMC Fam Pract. 2016; 17(1):112. PMID: 27542843.

Article26. Represas-Represas C, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Raviña A, Priegue-Carrera A, Botana-Rial M. study group of “Validity of COPD-6 in non-specialized healthcare settings”. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: validity and reliability of a portable device in non-specialized healthcare settings. PLoS One. 2016; 11(1):e0145571. PMID: 26726887.

Article27. Thorn J, Tilling B, Lisspers K, Jörgensen L, Stenling A, Stratelis G. Improved prediction of COPD in at-risk patients using lung function pre-screening in primary care: a real-life study and cost-effectiveness analysis. Prim Care Respir J. 2012; 21(2):159–166. PMID: 22270480.

Article28. van den Bemt L, Wouters BC, Grootens J, Denis J, Poels PJ, Schermer TR. Diagnostic accuracy of pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FEV6 from microspirometry to detect airflow obstruction in primary care: a randomised cross-sectional study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014; 24(1):14033. PMID: 25119686.

Article29. Melbye H, Medbø A, Crockett A. The FEV1/FEV6 ratio is a good substitute for the FEV1/FVC ratio in the elderly. Prim Care Respir J. 2006; 15(5):294–298. PMID: 16979378.

Article30. Vandevoorde J, Verbanck S, Schuermans D, Kartounian J, Vincken W. Obstructive and restrictive spirometric patterns: fixed cut-offs for FEV1/FEV6 and FEV6. Eur Respir J. 2006; 27(2):378–383. PMID: 16452596.

Article31. Buffels J, Degryse J, Decramer M, Heyrman J. Spirometry and smoking cessation advice in general practice: a randomised clinical trial. Respir Med. 2006; 100(11):2012–2017. PMID: 16580189.

Article32. Kotz D, Wesseling G, Huibers MJ, van Schayck OC. Efficacy of confronting smokers with airflow limitation for smoking cessation. Eur Respir J. 2009; 33(4):754–762. PMID: 19129277.

Article33. McClure JB, Ludman EJ, Grothaus L, Pabiniak C, Richards J. Impact of a brief motivational smoking cessation intervention the Get PHIT randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009; 37(2):116–123. PMID: 19524389.34. Ojedokun J, Keane S, O’Connor K. Lung age bio-feedback using a portable lung age meter with brief advice during routine consultations promote smoking cessation? Know2quit multicenter randomized control trial. J Gen Pract (Los Angel). 2013; 1(123):2.35. Risser NL, Belcher DW. Adding spirometry, carbon monoxide, and pulmonary symptom results to smoking cessation counseling: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 1990; 5(1):16–22. PMID: 2405112.

Article36. Segnan N, Ponti A, Battista RN, Senore C, Rosso S, Shapiro SH, et al. A randomized trial of smoking cessation interventions in general practice in Italy. Cancer Causes Control. 1991; 2(4):239–246. PMID: 1873454.

Article37. Sippel JM, Osborne ML, Bjornson W, Goldberg B, Buist AS. Smoking cessation in primary care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 1999; 14(11):670–676. PMID: 10571715.

Article38. Takagi H, Morio Y, Ishiwata T, Shimada K, Kume A, Miura K, et al. Effect of telling patients their “spirometric-lung-age” on smoking cessation in Japanese smokers. J Thorac Dis. 2017; 9(12):5052–5060. PMID: 29312710.

Article39. Walker WB, Franzini LR. Low-risk aversive group treatments, physiological feedback, and booster sessions for smoking cessation. Behav Ther. 1985; 16(3):263–274.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Benefits and Harms of Breast Screening: Focused on Updated Korean Guideline for Breast Cancer Screening

- Screening for Depression in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review

- Updated view on the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea

- Predictors of Mortality in Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- An Introduction of the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis