Healthc Inform Res.

2022 Jan;28(1):25-34. 10.4258/hir.2022.28.1.25.

Impact of Universal Suicide Risk Screening in a Pediatric Emergency Department: A Discrete Event Simulation Approach

- Affiliations

-

- 1Emergency Medicine Section of Data Analytics, Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

- 2Department of Engineering Management and Systems Engineering, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

- 3Division of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

- 4Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Sidra Medicina, Al Gharafa, Doha, Qatar

- 5Emergency Medicine and Trauma Center, Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

- KMID: 2526491

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2022.28.1.25

Abstract

Objectives

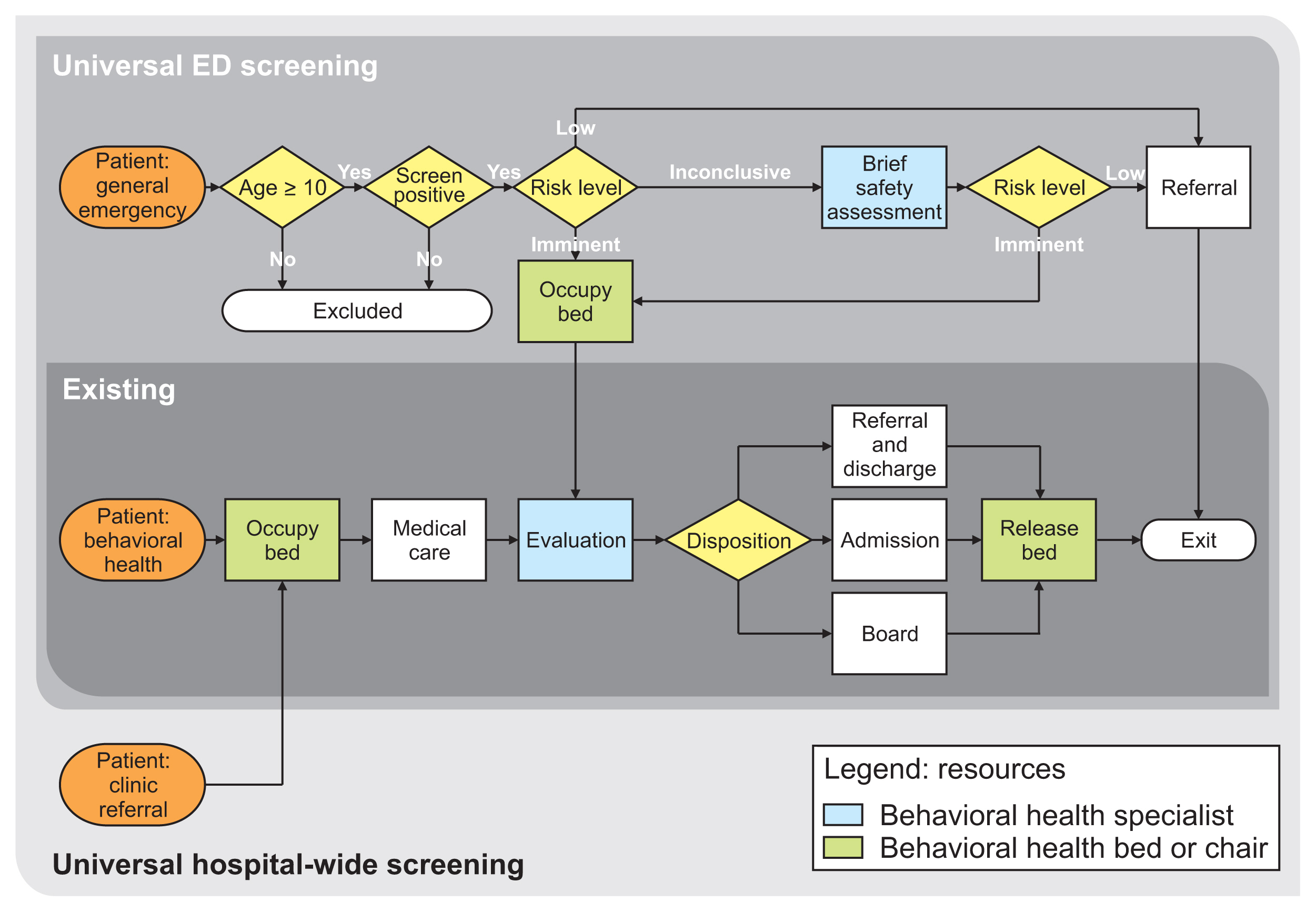

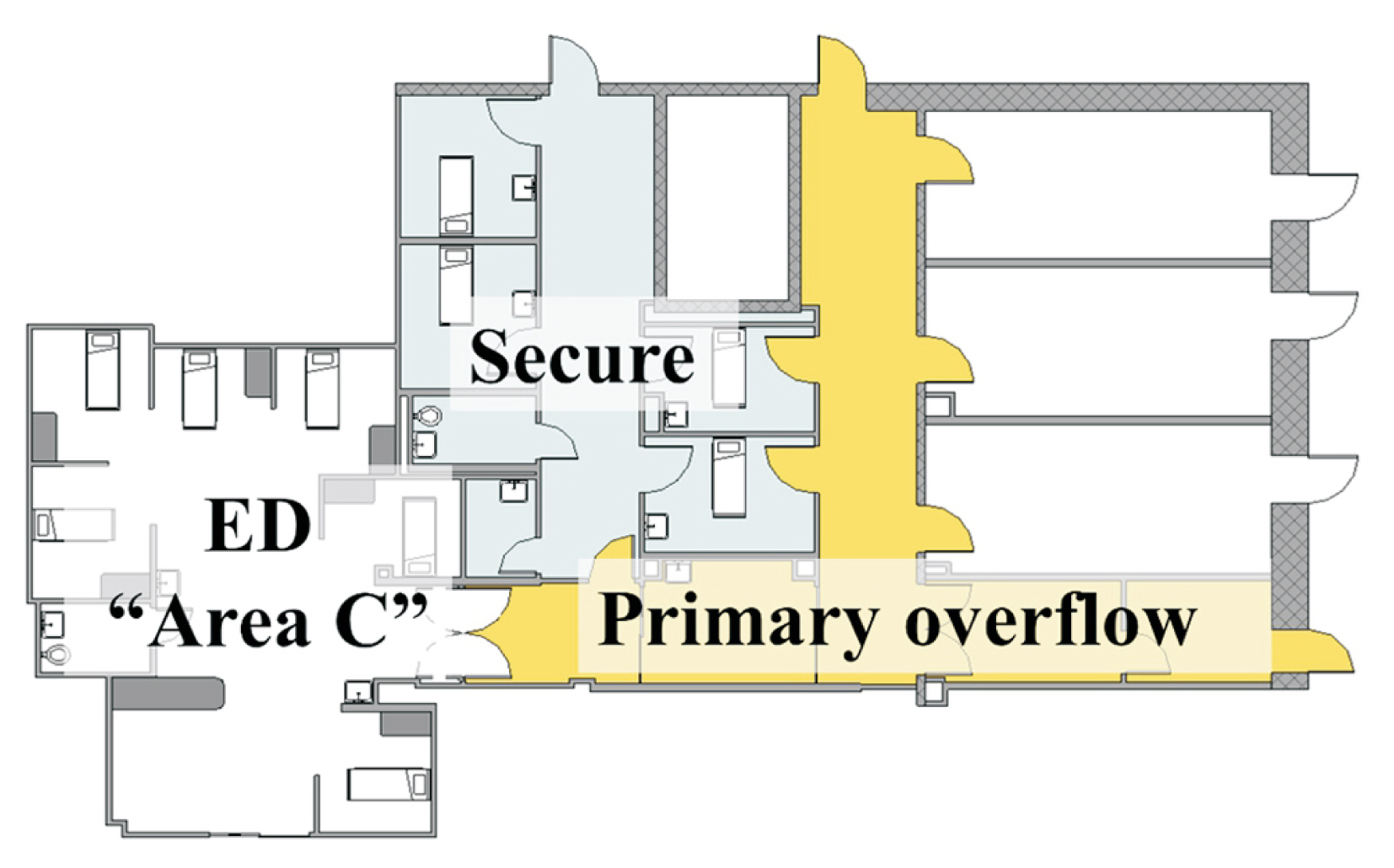

The aim of this study was to use discrete event simulation (DES) to model the impact of two universal suicide risk screening scenarios (emergency department [ED] and hospital-wide) on mean length of stay (LOS), wait times, and overflow of our secure patient care unit for patients being evaluated for a behavioral health complaint (BHC) in the ED of a large, academic children’s hospital.

Methods

We developed a conceptual model of BHC patient flow through the ED, incorporating anticipated system changes with both universal suicide risk screening scenarios. Retrospective site-specific patient tracking data from 2017 were used to generate model parameters and validate model output metrics with a random 50/50 split for derivation and validation data.

Results

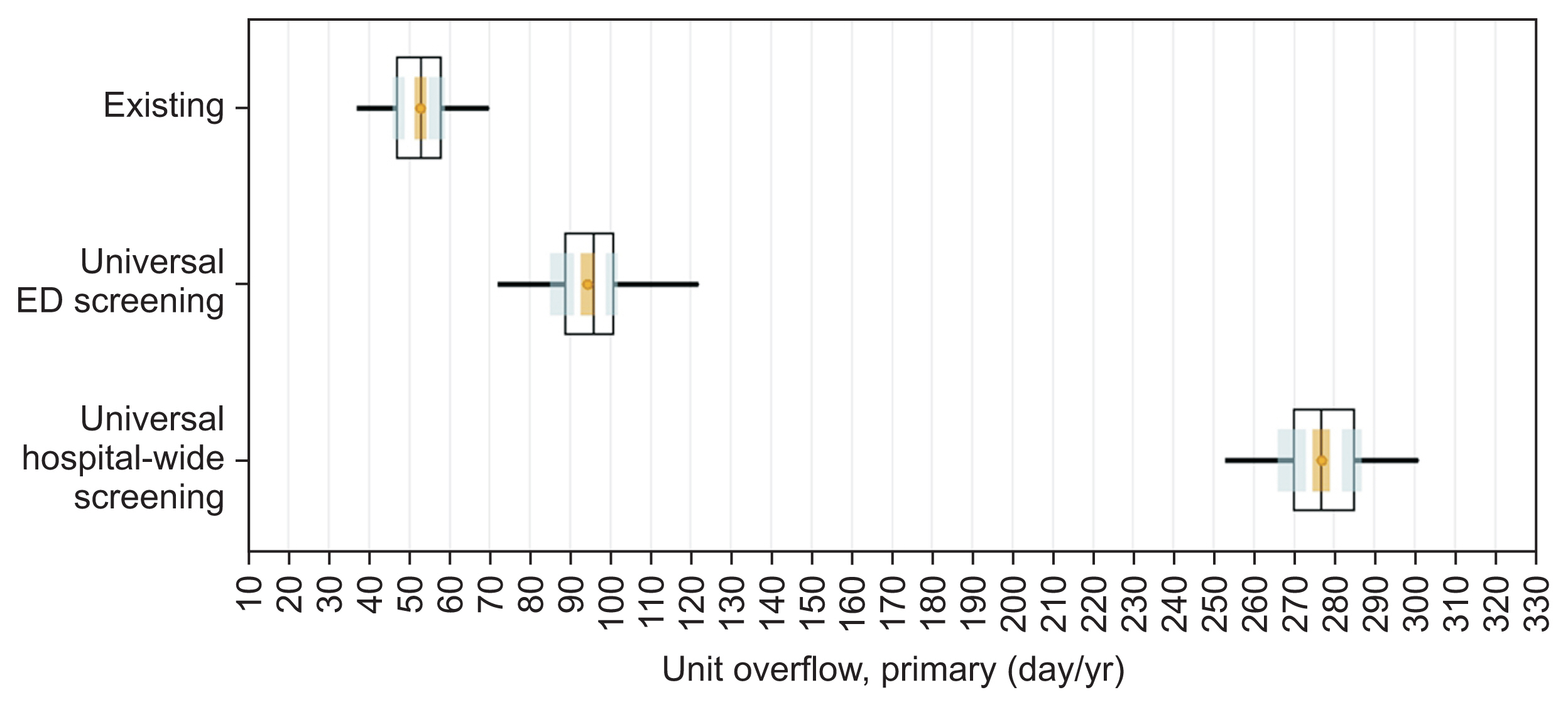

The model predicted small increases (less than 1 hour) in LOS and wait times for our BHC patients in both universal screening scenarios. However, the days per year in which the ED experienced secure unit overflow increased (existing system: 52.9 days; 95% CI, 51.5–54.3 days; ED: 94.4 days; 95% CI, 92.6–96.2 days; and hospital-wide: 276.9 days; 95% CI, 274.8–279.0 days).

Conclusions

The DES model predicted that implementation of either universal suicide risk screening scenario would not severely impact LOS or wait times for BHC patients in our ED. However, universal screening would greatly stress our existing ED capacity to care for BHC patients in secure, dedicated patient areas by creating more overflow.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B. Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US Emergency Departments, 2007–2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019; 173(6):598–600.

Article2. Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020; (362):1–8.3. The Joint Commission. Joint Commission Perspectives [Internet]. Washington (DC): The Joint Commission;2020. [cited at 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/suicide-prevention/april2020_faq_suicideriskreductioninnonpsychiatricareas.pdf .4. Fontanella CA, Warner LA, Steelesmith D, Bridge JA, Sweeney HA, Campo JV. Clinical profiles and health services patterns of medicaid-enrolled youths who died by suicide. JAMA Pediatr. 2020; 174(5):470–7.

Article5. Ruch DA, Steelesmith DL, Warner LA, Bridge JA, Campo JV, Fontanella CA. Health services use by children in the welfare system who died by suicide. Pediatrics. 2021; 147(4):e2020011585.

Article6. Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. Sentinel Event Alert. 2016; (56):1–7.7. Horowitz LM, Ballard ED, Pao M. Suicide screening in schools, primary care and emergency departments. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009; 21(5):620–7.

Article8. Babulak E, Wang M. Discrete event simulation: state of the art. Goti A, editor. Discrete event simulations. London, UK: InTech;2010.

Article9. Genuis ED, Doan Q. The effect of medical trainees on pediatric emergency department flow: a discrete event simulation modeling study. Acad Emerg Med. 2013; 20(11):1112–20.

Article10. The Joint Commission. Suicide prevention resources to support Joint Commission accredited organizations implementation of NPSG 15.01.01 [Internet]. Washington (DC): The Joint Commission;2018. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/suicide-prevention/pages-from-suicide_prevention_compendium_5_11_20_updated-july2020_ep2.pdf .11. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Gelenberg AJ, Katzelnick DJ, Jefferson JW, Modell JG. Feasibility and validation of a computer-automated Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale using interactive voice response technology. J Psychiatr Res. 2010; 44(16):1224–8.

Article12. Roaten K, Johnson C, Genzel R, Khan F, North CS. Development and implementation of a universal suicide risk screening program in a safety-net hospital system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018; 44(1):4–11.

Article13. Palmer S, Ipsen T. Caring for our children: a look at patient experience in a pediatric setting. Nashville (TN): The Beryl Institute;2020.14. Chang AM, Lin A, Fu R, McConnell KJ, Sun B. Associations of emergency department length of stay with publicly reported quality-of-care measures. Acad Emerg Med. 2017; 24(2):246–50.

Article15. Abo-Hamad W, Arisha A. Simulation-based framework to improve patient experience in an emergency department. Eur J Oper Res. 2013; 224(1):154–66.

Article16. Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, Martinez P, Njai R, Holland KM. Mental health-related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(45):1675–80.17. Wright JH, Caudill R. Remote treatment delivery in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom. 2020; 89(3):130–2.

Article18. Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020; 4(6):421.

Article19. Adams JM, van Dahlen B. Preventing suicide in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2021; 136(1):3–5.

Article20. Latif F, Patel S, Badolato G, McKinley K, Chan-Salcedo C, Bannerman R, et al. Improving Youth Suicide Risk Screening and Assessment in a Pediatric Hospital Setting by Using The Joint Commission Guidelines. Hosp Pediatr. 2020; 10(10):884–92.

Article21. Fazel S, Runeson B. Suicide. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(3):266–74.

Article22. Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, et al. Vital signs: trends in state suicide rates – United States, 1999–2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide - 27 states, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018; 67(22):617–24.23. Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute. Effects of a COVID-induced economic recession (COVID-19 Impact Series, Volume 1) [Internet]. Dallas (TX): Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute;2020. [cited at 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://mmhpi.org/topics/policy-research/covid-impact-series-volume1/ .24. Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019: a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020; 77(11):1093–4.25. Kumar AP, Kapur R. Discrete simulation application-scheduling staff for the emergency room. In : Proceedings of the 21st Conference on Winter Simulation; 1989 Dec 4–6; Washington, DC. p. 1112–20.

Article26. Day TE, Sarawgi S, Perri A, Nicolson SC. Reducing postponements of elective pediatric cardiac procedures: analysis and implementation of a discrete event simulation model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015; 99(4):1386–91.

Article27. McKinley KW, Babineau J, Roskind CG, Sonnett M, Doan Q. Discrete event simulation modelling to evaluate the impact of a quality improvement initiative on patient flow in a paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020; 37(4):193–9.

Article28. Rutberg MH, Wenczel S, Devaney J, Goldlust EJ, Day TE. Incorporating discrete event simulation into quality improvement efforts in health care systems. Am J Med Qual. 2015; 30(1):31–5.

Article29. Halpern P, Goldberg SA, Keng JG, Koenig KL. Principles of emergency department facility design for optimal management of mass-casualty incidents. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012; 27(2):204–12.

Article30. McEnany FB, Ojugbele O, Doherty JR, McLaren JL, Leyenaar JK. Pediatric mental health boarding. Pediatrics. 2020; 146(4):e20201174.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Evaluation of Algorithm-Based Simulation Scenario for Emergency Measures with High-Risk Newborns Presenting with Apnea

- Can a Suicide Prevention Law decrease the suicide rate in Korea?

- The effect of paramedic’s emergency patient simulation training - course using standardized communication tools and simulation

- The Impact of a Simulation-based Education Program for Emergency Airway Management on Self-efficacy and Clinical Performance among Nurses

- Impact of discharge against medical advice on emergency department revisit among suicide attempters