J Rhinol.

2021 Jul;28(2):73-80. 10.18787/jr.2020.00346.

Contemporary Review of Olfactory Dysfunction in COVID-19

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Guro Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2518671

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.18787/jr.2020.00346

Abstract

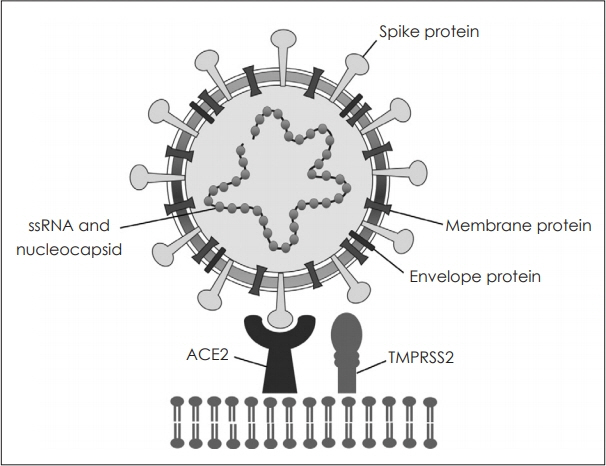

- The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an extreme threat to international health care, resulting in more than two million deaths. Data reveal that olfactory disorder is a characteristic symptom of COVID-19 and has unique clinical manifestations. The olfactory dysfunction induced by COVID-19 has sudden onset, short duration, and rapid recovery, with anosmia often the only symptom. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) affects the human body by binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) of the olfactory epithelium. However, the etiology of COVID-19-induced olfactory dysfunction is unclear. In many countries, vaccines for COVID-19 in human are beginning to be administered. Conventional conservative treatments are common for olfactory disorders caused by COVID-19. Rhinologists should be aware of olfactory dysfunction to avoid delayed diagnosis of COVID-19. The article reviews the latest scientific evidence of anosmia in COVID-19.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1199–207.2. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1708–20.3. Marchese-Ragona R, Ottaviano G, Nicolai P, Vianello A, Carecchio M. Sudden hyposmia as a prevalent symptom of COVID-19 infection. medRxiv;2020.4. Heidari F, Karimi E, Firouzifar M, Khamushian P, Ansari R, Ardehali MM, et al. Anosmia as a prominent symptom of COVID-19 infection. Rhinology. 2020; 58:302–3.5. Gane SB, Kelly C, Hopkins C. Isolated sudden onset anosmia in COVID-19 infection. A novel syndrome? Rhinology. 2020; 58:299–301.6. Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019; 17:181–92.7. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020; 395:565–74.8. Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, Feng J, Zhou H, Li X, et al. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life Sci. 2020; 63:457–60.9. Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi ZL. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021; 19:141–54.10. He L, Mae MA, Sun Y, Muhl L, Nahar K, Liebanas EV, et al. Pericyte-specific vascular expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2-implications for microvascular inflammation and hypercoagulopathy in COVID-19 patients. BioRxiv;2020.11. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020; 77:683–90.12. Lovato A, de Filippis C, Marioni G. Upper airway symptoms in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Am J Otolaryngol. 2020; 41:102474.13. Jang JG, Hur J, Choi EY, Hong KS, Lee W, Ahn JH. Prognostic Factors for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Daegu, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35:e209.14. Vaira LA, Salzano G, Fois AG, Piombino P, De Riu G. Potential pathogenesis of ageusia and anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020; 10:1103–4.15. Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim SW. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35:e174.16. Beltrán-Corbellini Á, Chico-García JL, Martínez-Poles J, Rodríguez-Jorge F, Natera-Villalba E, Gómez-Corral J, et al. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case–control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020; 27:1738–41.17. Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020; 277:2251–61.18. Klopfenstein T, Toko L, Royer PY, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V, Zayet S. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020; 50:436–9.19. Kaye R, Chang CD, Kazahaya K, Brereton J, Denneny III JC. COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020; 163:132–4.20. Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, Pirina P, Madeddu G, De Vito A, et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: Single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. 2020; 42:1252–8.21. Duncan HJ, Seiden AM. Long-term follow-up of olfactory loss secondary to head trauma and upper respiratory tract infection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 121:1183–7.22. Reden J, Mueller A, Mueller C, Konstantinidis I, Frasnelli J, Landis BN, et al. Recovery of olfactory function following closed head injury or infections of the upper respiratory tract. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006; 132:265–9.23. Reden J, Herting B, Lill K, Kern R, Hummel T. Treatment of postinfectious olfactory disorders with minocycline: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Laryngoscope. 2011; 121:679–82.24. Chiesa-Estomba CM, Lechien JR, Radulesco T, Michel J, Sowerby LJ, Hopkins C, et al. Patterns of smell recovery in 751 patients affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Neurol. 2020; 27:2318–21.25. Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, Moore-Gillon V, Shaman P, Mester AF, et al. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991; 117:519–28.26. Hou YJ, Okuda K, Edwards CE, Martinez DR, Asakura T, Dinnon III KH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract. Cell. 2020; 182:429–46.27. Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, Mothes R, Franz J, Laue M, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as port of Central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021; 24:168–75.28. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1177–9.29. Bilinska K, Jakubowska P, Von Bartheld CS, Butowt R. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Entry Proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in Cells of the Olfactory Epithelium: Identification of Cell Types and Trends with Age. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020; 11:1555–62.30. Bryche B, St Albin A, Murri S, Lacôte S, Pulido C, Ar Gouilh M, et al. Massive transient damage of the olfactory epithelium associated with infection of sustentacular cells by SARS-CoV-2 in golden Syrian hamsters. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 89:579–86.31. Torabi A, Mohammadbagheri E, Akbari Dilmaghani N, Bayat AH, Fathi M, Vakili K, et al. Proinflammatory Cytokines in the Olfactory Mucosa Result in COVID-19 Induced Anosmia. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020; 11:1909–13.32. Vogalis F, Hegg CC, Lucero MT. Ionic conductances in sustentacular cells of the mouse olfactory epithelium. J Physiol. 2005; 562:785–99.33. Plasschaert LW, Žilionis R, Choo-Wing R, Savova V, Knehr J, Roma G, et al. A single-cell atlas of the airway epithelium reveals the CFTR-rich pulmonary ionocyte. Nature. 2018; 560:377–81.34. Brown LS, Foster CG, Courtney JM, King NE, Howells DW, Sutherland BA. Pericytes and neurovascular function in the healthy and diseased brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019; 13:1–9.35. Laurendon T, Radulesco T, Mugnier J, Gérault M, Chagnaud C, El Ahmadi AA, et al. Bilateral transient olfactory bulb edema during COVID-19–related anosmia. Neurology. 2020; 95:224–5.36. Eliezer M, Hamel AL, Houdart E, Herman P, Housset J, Jourdaine C, et al. Loss of smell in patients with COVID-19: MRI data reveal a transient edema of the olfactory clefts. Neurology. 2020; 95:3145–52.37. von Bartheld CS, Hagen MM, Butowt R. Prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis reveals significant ethnic differences. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020; 11:2944–61.38. Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020; 581:221–4.39. Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020; 182:812–27.40. Grubaugh ND, Hanage WP, Rasmussen AL. Making sense of mutation: what D614G means for the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. Cell. 2020; 182:794–5.41. Williams FM, Freydin M, Mangino M, Couvreur S, Visconti A, Bowyer RC, et al. Self-reported symptoms of covid-19 including symptoms most predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection, are heritable. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2020; 23:316–21.42. Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z, Wan S, Huang P, Sun X, et al. Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell Discovery. 2020; 6:1–4.43. Renieri A, Benetti E, Tita R, Spiga O, Ciolfi A, Birolo G, et al. ACE2 variants underlie interindividual variability and susceptibility to COVID-19 in Italian population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020; 28:1602–14.44. Santos NPC, Khayat AS, Rodrigues JCG, Pinto PC, Araujo GS, Pastana LF, et al. TMPRSS2 variants and their susceptibility to COVID-19: focus in East Asian and European populations. medRxiv;2020.45. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19-preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384:693–704.46. Johnson RM, Vinetz JM. Dexamethasone in the management of COVID-19. BMJ. 2020; 370:m2648.47. Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Homoud AH, Memish ZA. Remdesivir as a possible therapeutic option for the COVID-19. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020; 34:101615.48. Madsen LW. Remdesivir for the Treatment of COVID-19-Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:1813–26.49. Small CB, Hernandez J, Reyes A, Schenkel E, Damiano A, Stryszak P, et al. Efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate nasal spray in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 116:1275–81.50. Alobid I, Benitez P, Cardelús S, de Borja Callejas F, Lehrer-Coriat E, Pujols L, et al. Oral plus nasal corticosteroids improve smell, nasal congestion, and inflammation in sino-nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2014; 124:50–6.51. Heilmann S, Huettenbrink KB, Hummel T. Local and systemic administration of corticosteroids in the treatment of olfactory loss. Am J Rhinol. 2004; 18:29–33.52. Baradaranfar MH, Ahmadi ZS, Dadgarnia MH, Bemanian MH, Atighechi S, Karimi G, et al. Comparison of the effect of endoscopic sinus surgery versus medical therapy on olfaction in nasal polyposis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014; 271:311–6.53. Schriever V, Merkonidis C, Gupta N, Hummel C, Hummel T. Treatment of smell loss with systemic methylprednisolone. Rhinology. 2012; 50:284–9.54. Ikeda K, Sakurada T, Suzaki Y, Takasaka T. Efficacy of systemic corticosteroid treatment for anosmia with nasal and paranasal sinus disease. Rhinology. 1995; 33:162–5.55. Blomqvist EH, Lundblad L, Bergstedt H, Stjärne P. Placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study evaluating the efficacy of fluticasone propionate nasal spray for the treatment of patients with hyposmia/anosmia. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003; 123:862–8.56. Fukazawa K. A local steroid injection method for olfactory loss due to upper respiratory infection. Chem Senses. 2005; 30:212–3.57. Damm M, Pikart LK, Reimann H, Burkert S, Göktas Ö, Haxel B, et al. Olfactory training is helpful in postinfectious olfactory loss: a randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Laryngoscope. 2014; 124:826–31.58. Pekala K, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Efficacy of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016; 6:299–307.59. Hura N, Xie DX, Choby GW, Schlosser RJ, Orlov CP, Seal SM, et al. Treatment of post-viral olfactory dysfunction: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020; 10:1065–86.60. Blakemore LJ, Trombley PQ. Zinc as a neuromodulator in the central nervous system with a focus on the olfactory bulb. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017; 11:1–20.61. Miwa T, Ikeda K, Ishibashi T, Kobayashi M, Kondo K, Matsuwaki Y, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of olfactory dysfunction—Secondary publication. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019; 46:653–62.62. Aiba MS, Junko Mori, Kohji Matsumoto, Kenta Tomiyama, Fumiyuki Okuda, Yoshiaki Nakai, Tsunemasa . Effect of zinc sulfate on sensorineural olfactory disorder. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998; 118:202–4.63. Henkin RI, Velicu I, Schmidt L. An open-label controlled trial of theophylline for treatment of patients with hyposmia. Am J Med Sci. 2009; 337:396–406.64. Ruhnau KJ, Meissner H, Finn JR, Reljanovic M, Lobisch M, Schütte K, et al. Effects of 3-week oral treatment with the antioxidant thioctic acid (α-lipoic acid) in symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabet Med. 1999; 16:1040–3.65. Hummel T, Heilmann S, Hüttenbriuk KB. Lipoic acid in the treatment of smell dysfunction following viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. Laryngoscope. 2002; 112:2076–80.66. Welge-Lüssen A, Wolfensberger M. Olfactory disorders following upper respiratory tract infections. Taste and Smell. Karger Publishers. 2006; 63:125–32.67. Rawson N, LaMantia AS. A speculative essay on retinoic acid regulation of neural stem cells in the developing and aging olfactory system. Exp Gerontol. 2007; 42:46–53.68. Reden J, Lill K, Zahnert T, Haehner A, Hummel T. Olfactory function in patients with postinfectious and posttraumatic smell disorders before and after treatment with vitamin A: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Laryngoscope. 2012; 122:1906–9.69. Yrjänheikki J, Keinänen R, Pellikka M, Hökfelt T, Koistinaho J. Tetracyclines inhibit microglial activation and are neuroprotective in global brain ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998; 95:15769–74.70. Thomas M, Le W. Minocycline: neuroprotective mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2004; 10:679–86.71. Ehrenberger K, Felix D. Caroverine depresses the activity of cochlear glutamate receptors in guinea pigs: in vivo model for druginduced neuroprotection? Neuropharmacology. 1992; 31:1259–63.72. Pujol R, Puel JL. Excitotoxicity, synaptic repair, and functional recovery in the mammalian cochlea: a review of recent findings. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999; 884:249–54.73. Quint C, Temmel AF, Hummel T, Ehrenberger K. The quinoxaline derivative caroverine in the treatment of sensorineural smell disorders: a proof-of-concept study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002; 122:877–81.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A review on photobiomodulation therapy for olfactory dysfunction caused by COVID-19

- Comparative Analysis of Olfactory and Gustatory Function of Patients With COVID-19 Olfactory Dysfunction and Non-COVID-19 Postinfectious Olfactory Dysfunction

- Practical Review of Olfactory Training and COVID-19

- The Sniffing Bead System as a Useful Diagnostic Tool for Olfactory Dysfunction in COVID-19

- Characteristics and Prognosis of COVID-19 Induced Olfactory and Gustatory Dysfunction in Daegu