A National Study of Life-Sustaining Treatments in South Korea: What Factors Affect Decision-Making?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Education and Medical Humanities, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Medical Education and Medical Humanities, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2514940

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2020.803

Abstract

- Purpose

This cross-sectional study investigated the status of life-sustaining treatment (LST) practices and identified characteristics and factors influencing decision-making practices.

Materials and Methods

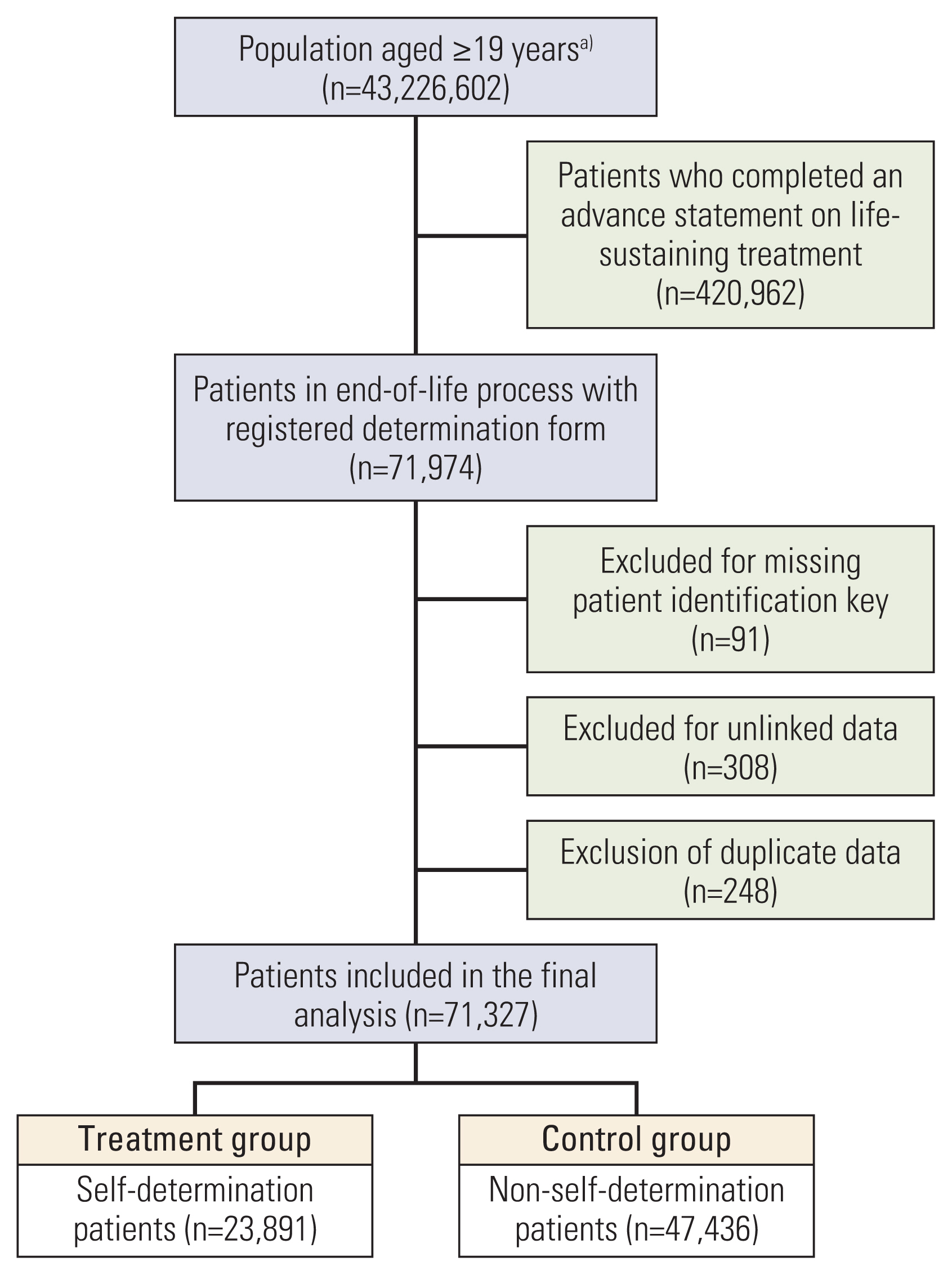

The National Agency for Management of Life-sustaining Treatment retains records provided by doctors regarding patients subject to LST implementation. A total of 71,327 patients receiving LST were identified. We analyzed all nationally reported data between February 2018 and October 2019. Indicators such as the proportion of deaths, records for decision to terminate LST, implementation of LST records, and registration of Advance Statements on LST were analyzed.

Results

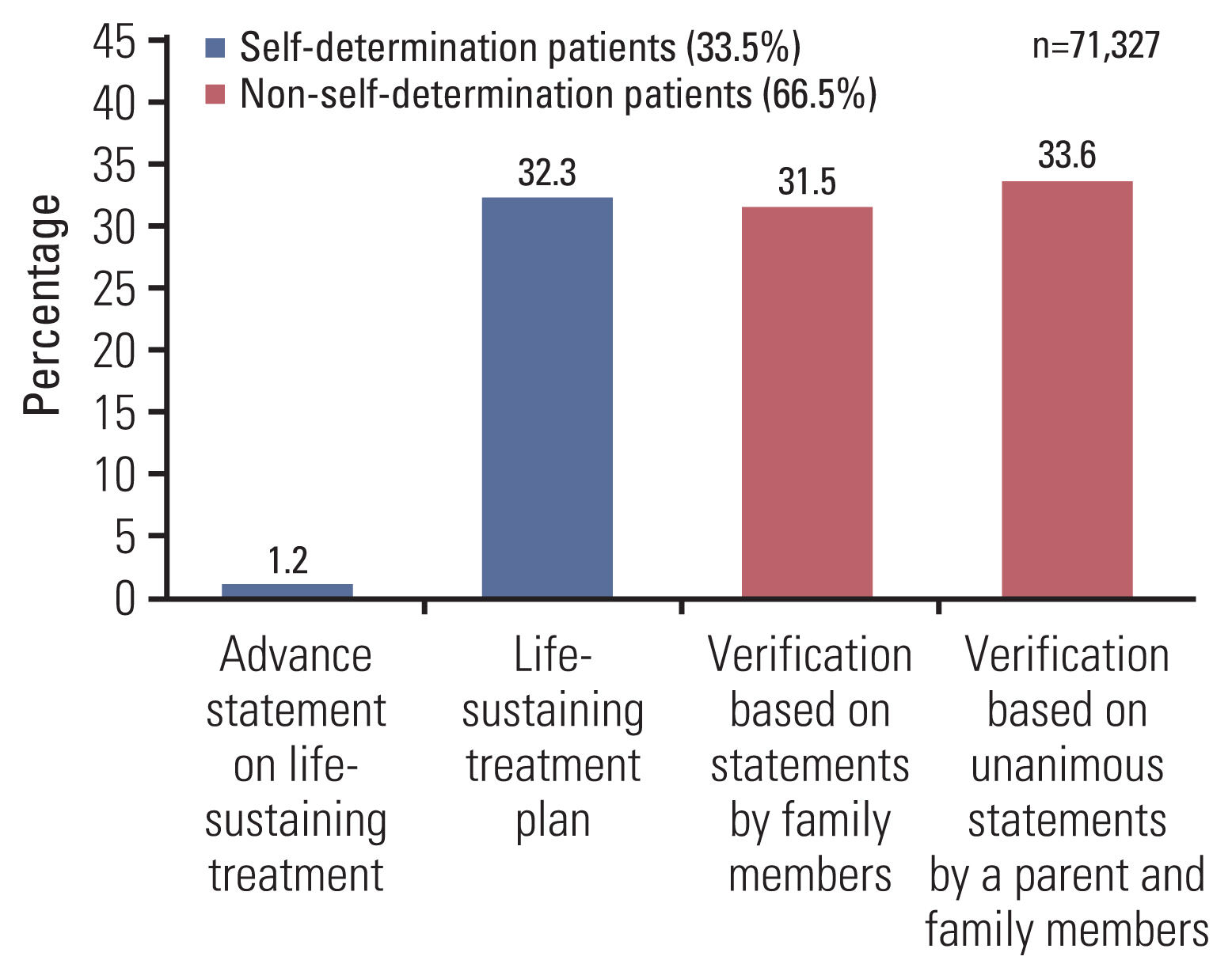

A total of 67,252 (94.3%) end-of life decisions were implemented in South Korea. The proportion of deaths preceded by a LST plan, non-self-determination LST decision, and any advance statements was 33.5% (23,891/71,327), 66.5% (47,436/71,327), and 1.2% (890/71,327), respectively. The logistic regression model revealed that self-determination to terminate LST was more frequent for men than for women and higher for those aged 30-69. Disability (odds ratio [OR], 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56 to 0.61), living in non-metropolitan areas (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.86), and disease comorbidity was independently associated with a low level of self-determination.

Conclusion

After the implementation of the new LST Act, about a third of patients in end-of-life process made decisions regarding their medical LST. However, family members still play a major role in LST decisions where the patient’s intention cannot be verified. Decisions related to LST are predominantly made when death is imminent. Thus, it is necessary to increase awareness of end-of-life LST decision-making among medical staff and the public.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

Preparation and Practice of the Necessary Documents in Hospital for the “Act on Decision of Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End-of-Life”

Sun Kyung Baek, Hwa Jung Kim, Jung Hye Kwon, Ha Yeon Lee, Young-Woong Won, Yu Jung Kim, Sujin Baik, Hyewon Ryu

Cancer Res Treat. 2021;53(4):926-934. doi: 10.4143/crt.2021.326.Analysis of Cancer Patient Decision-Making and Health Service Utilization after Enforcement of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act in Korea

Dalyong Kim, Shin Hye Yoo, Seyoung Seo, Hyun Jung Lee, Min Sun Kim, Sung Joon Shin, Chi-Yeon Lim, Do Yeun Kim, Dae Seog Heo, Chae-Man Lim

Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54(1):20-29. doi: 10.4143/crt.2021.131.Will implementation of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act reduce the incidence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation?

In-Ae Song

Acute Crit Care. 2022;37(2):256-257. doi: 10.4266/acc.2022.00668.Recent Trends in the Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment in Patients with Acute Cerebrovascular Disease : 2017–2021

Seung Hwan Kim, Ji Hwan Jang, Young Zoon Kim, Kyu Hong Kim, Taek Min Nam

J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2024;67(1):73-83. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2023.0074.

Reference

-

References

1. Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, Sjokvist P, Dodek P, Griffith L, et al. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:1123–32.

Article2. Yaguchi A, Truog RD, Curtis JR, Luce JM, Levy MM, Melot C, et al. International differences in end-of-life attitudes in the intensive care unit: results of a survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:1970–5.3. Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Myatra SN, Chan YH, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175:363–71.

Article4. Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39:1174–89.

Article5. Crawley LM, Marshall PA, Lo B, Koenig BA. End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. Strategies for culturally effective end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2002; 136:673–9.

Article6. Sprung CL, Truog RD, Curtis JR, Joynt GM, Baras M, Michalsen A, et al. Seeking worldwide professional consensus on the principles of end-of-life care for the critically ill. The Consensus for Worldwide End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care Units (WELPICUS) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 190:855–66.

Article7. van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet. 2003; 362:345–50.

Article8. National Law Information Center. Act on Decisions on life-sustaining treatment for patients in hospice and palliative care or at the end of life [Internet]. Sejong: National Law Information Center;c2016. [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: http://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=life-sustaining+treatment+&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor0 .9. Baek SK, Chang HJ, Byun JM, Han JJ, Heo DS. The association between end-of-life care and the time interval between provision of a do-not-resuscitate consent and death in cancer patients in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 49:502–8.

Article10. Lee JK, Keam B, An AR, Kim TM, Lee SH, Kim DW, et al. Surrogate decision-making in Korean patients with advanced cancer: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2013; 21:183–90.

Article11. Kim JS, Yoo SH, Choi W, Kim Y, Hong J, Kim MS, et al. Implication of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act on end-of-life care for Korean terminal patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2020; 52:917–24.

Article12. Kong BH, An HJ, Kim HS, Ha SY, Kim IK, Lee JE, et al. Experience of advance directives in a hospice center. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:151–4.

Article13. Searight HR, Gafford J. Cultural diversity at the end of life: issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2005; 71:515–22.14. Koh M, Hwee PC. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: how Asia differs from the West. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175:371–2.15. The AM, Hak T, Koeter G, van Der Wal G. Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study. BMJ. 2000; 321:1376–81.

Article16. Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010; 376:1339–46.

Article17. Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, Kent S, Kim J, Herbst N, et al. Approximately one In three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017; 36:1244–51.

Article18. Collier J, Kelsberg G, Safranek S. How well do POLST forms assure that patients get the end-of-life care they requested? [Internet]. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Library Systems;2018. [cited 2020 Sep 9]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10355/63149 .19. Petrova M, Riley J, Abel J, Barclay S. Crash course in EPaCCS (Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Systems): 8 years of successes and failures in patient data sharing to learn from. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018; 8:447–55.20. Park HY, Kim YA, Sim JA, Lee J, Ryu H, Lee JL, et al. Attitudes of the general public, cancer patients, family caregivers, and physicians toward advance care planning: a nationwide survey before the enforcement of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019; 57:774–82.

Article21. Kim JW, Choi JY, Jang WJ, Choi YJ, Choi YS, Shin SW, et al. Completion rate of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer: a preliminary, cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019; 18:84.

Article22. Jang Y, Kim SY, Chang S. Correlates of the attitude toward life-sustaining treatment: a study with older adults in South Korea. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2018; 86:415–25.23. Ryu JY, Bae H, Kenji H, Xiaomei Z, Kwon I, Ahn KJ. Physicians’ attitude toward the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment: a comparison between Korea, Japan, and China. Death Stud. 2016; 40:630–7.

Article24. Hong JH, Kwon JH, Kim IK, Ko JH, Kang YJ, Kim HK. Adopting advance directives reinforces patient participation in end-of-life care discussion. Cancer Res Treat. 2016; 48:753–8.

Article25. Kim DY, Lee SM, Lee KE, Lee HR, Kim JH, Lee KW, et al. An evaluation of nutrition support for terminal cancer patients at teaching hospitals in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2006; 38:214–7.

Article26. Jho HJ, Nam EJ, Shin IW, Kim SY. Changes of end of life practices for cancer patients and their association with hospice palliative care referral over 2009–2014: a single institution study. Cancer Res Treat. 2020; 52:419–25.

Article27. Zive DM, Jimenez VM, Fromme EK, Tolle SW. Changes over time in the Oregon Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Registry: a study of two decedent cohorts. J Palliat Med. 2019; 22:500–7.

Article28. Statistics Korea. Causes of death in 2018 [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2019. [cited 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/6/2/index.board .29. Volker DL, Divin-Cosgrove C, Harrison T. Advance directives, control, and quality of life for persons with disabilities. J Palliat Med. 2013; 16:971–4.

Article30. Stein GL, Kerwin J. Disability perspectives on health care planning and decision-making. J Palliat Med. 2010; 13:1059–64.

Article31. Wicki MT. Withholding treatment and intellectual disability: Second survey on end-of-life decisions in Switzerland. SAGE Open Med. 2016; 4:2050312116652637.

Article32. Mitchell SE, Weigel GM, Stewart SK, Mako M, Loughnane JF. Experiences and perspectives on advance care planning among individuals living with serious physical disabilities. J Palliat Med. 2017; 20:127–33.

Article33. Korean Statistical Information Service. Statistics Korea [Internet]. Daejeon: Korean Statistical Information Service;2020. [cited 2020 Sep 9]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/index/index.do .34. Social Security Information System. Social security statistics [Internet]. Sejong: Social Security Information System;2020. [cited 2020 Sep 9]. Available from: https://www.bokjiro.go.kr/nwel/welfareinfo/sociguastat/retrieveSociGuaStatList.do .

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Factors associated with the Decision to Withhold Life-Sustaining Treatments among Middle-Aged and Older Adults Who Die in Hospital

- Family Decision-Making to Withdraw Life-Sustaining Treatment for Terminally-Ill Patients in an Unconscious State

- Changes in Life-sustaining Treatment in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients after Signing a Do-Not-Resuscitate Order

- Decision-making regarding withdrawal of lifesustaining treatment and the role of intensivists in the intensive care unit: a single-center study

- The Problems and the Improvement Plan of the Hospice/Palliative Care and Dying Patient's Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act