Ann Lab Med.

2021 May;41(3):293-301. 10.3343/alm.2021.41.3.293.

In Vitro Activity of the Novel Tetracyclines, Tigecycline, Eravacycline, and Omadacycline, Against Moraxella catarrhalis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Infectious Diseases and Shenzhen Key Laboratory for Endogenous Infection, Shenzhen Nanshan People’s Hospital, Shenzhen University of School Medicine, Shenzhen, China

- 2Quality Control Center of Hospital Infection Management of Shenzhen, Shenzhen Nanshan People’s Hospital of Guangdong Medical University, Shenzhen, China

- KMID: 2512687

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2021.41.3.293

Abstract

- Background

Tigecycline, eravacycline, and omadacycline are recently developed tetracyclines. Susceptibility of microbes to these tetracyclines and their molecular mechanisms have not been well elucidated. We investigated the susceptibility of Moraxella catarrhalis to tigecycline, eravacycline, and omadacycline and its resistance mechanisms against these tetracyclines.

Methods

A total of 207 non-duplicate M. catarrhalis isolates were collected from different inpatients. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the tetracyclines were determined by broth microdilution. Tigecycline-, eravacycline-, or omadacycline-resistant isolates were induced under In Vitro pressure. The tet genes and mutations in the 16S rRNA was detected by PCR and sequencing.

Results

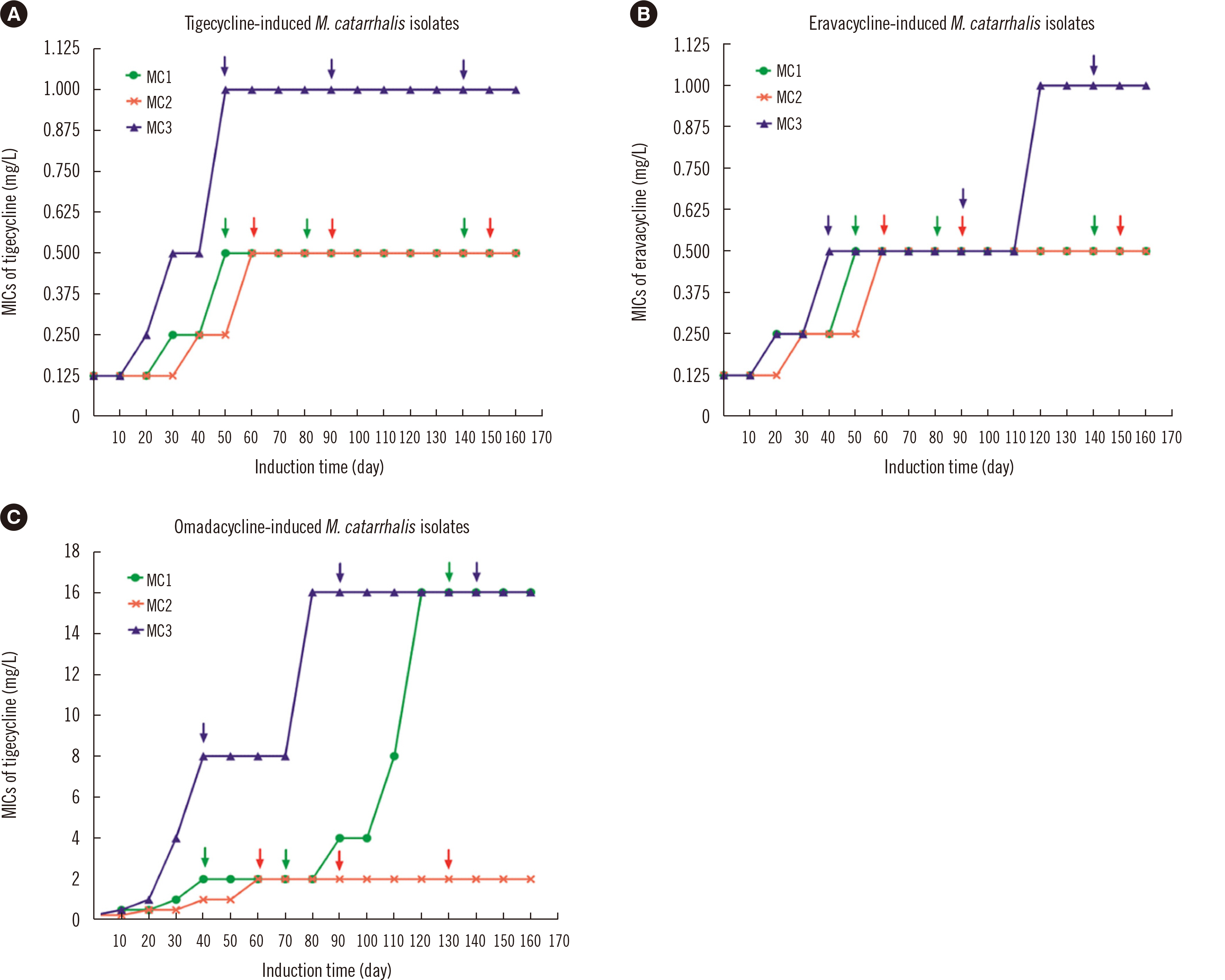

Eravacycline had a lower MIC50 (0.06 mg/L) than tigecycline (0.125 mg/L) or omadacycline (0.125 mg/L) against M. catarrhalis isolates. We found that 136 isolates (65.7%) had the tetB gene, and 15 (7.2%) isolates were positive for tetL; however, their presence was not correlated with high tigecycline, eravacycline, or omadacycline ( ≥ 1 mg/L) MICs.Compared with the initial MIC after 160 days of induction, the MICs of tigecycline or eravacycline against three M. catarrhalis isolates increased ≥ eight-fold, while those of omadacycline against two M. catarrhalis isolates increased 64-fold. Mutations in the 16S rRNA genes (C1036T and/or G460A) were observed in omadacycline-induced resistant isolates, and increased RR (the genes encoding 16SrRNA (four copies, RR1-RR4) copy number of 16S rRNA genes with mutations was associated with increased resistance to omadacycline.

Conclusions

Tigecycline, eravacycline, and omadacycline exhibited robust antimicrobial effects against M. catarrhalis. Mutations in the 16S rRNA genes contributed to omadacycline resistance in M. catarrhalis.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Gao Y, Lee J, Widmalm G, Im W. 2020; Preferred conformations of lipooligosaccharides and oligosaccharides of Moraxella catarrhalis. Glycobiology. 30:86–94. DOI: 10.1093/glycob/cwz086. PMID: 31616921.2. Ren D, Pichichero ME. 2016; Vaccine targets against Moraxella catarrhalis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 20:19–33. DOI: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1081686. PMID: 26565427. PMCID: PMC4720561.3. de Vries SP, Bootsma HJ, Hays JP, Hermans PW. 2009; Molecular aspects of Moraxella catarrhalis pathogenesis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 73:389–406. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-09. PMID: 19721084. PMCID: PMC2738133.4. Augustyniak D, Seredyński R, McClean S, Roszkowiak J, Roszniowski B, Smith DL, et al. 2018; Virulence factors of Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane vesicles are major targets for cross-reactive antibodies and have adapted during evolution. Sci Rep. 8:4955. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-23029-7. PMID: 29563531. PMCID: PMC5862889.

Article5. Spaniol V, Bernhard S, Aebi C. 2015; Moraxella catarrhalis AcrAB-OprM efflux pump contributes to antimicrobial resistance and is enhanced during cold shock response. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59:1886–94. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.03727-14. PMID: 25583725. PMCID: PMC4356836.6. Hsu SF, Lin YT, Chen TL, Siu LK, Hsueh PR, Huang ST, et al. 2012; Antimicrobial resistance of Moraxella catarrhalis isolates in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 45:134–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.09.004. PMID: 22154675.7. Shaikh SB, Ahmed Z, Arsalan SA, Shafiq S. 2015; Prevalence and resistance pattern of Moraxella catarrhalis in community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. Infect Drug Resist. 8:263–7. DOI: 10.2147/IDR.S84209. PMID: 26261422. PMCID: PMC4527568.8. Sánchez AR, Rogers RS 3rd, Sheridan PJ. 2004; Tetracycline and other tetracycline-derivative staining of the teeth and oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 43:709–15. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02108.x. PMID: 15485524.

Article9. Zhang Y, Zhang F, Wang H, Zhao C, Wang Z, Cao B, et al. 2016; Antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis isolated from community-acquired respiratory tract infections in China: results from the CARTIPS Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 5:36–41. DOI: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.03.002. PMID: 27436464.10. Nguyen F, Starosta AL, Arenz S, Sohmen D, Dönhöfer A, Wilson DN. 2014; Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance mechanisms. Biol Chem. 395:559–75. DOI: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0292. PMID: 24497223.

Article11. Mendez B, Tachibana C, Levy SB. 1980; Heterogeneity of tetracycline resistance determinants. Plasmid. 3:99–108. DOI: 10.1016/0147-619X(80)90101-8. PMID: 6801018. PMCID: PMC216488.

Article12. Chopra I, Roberts M. 2001; Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 65:232–6. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. PMID: 11381101. PMCID: PMC99026.

Article13. Roberts MC. 2005; Update on acquired tetracycline resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 245:195–203. DOI: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.034. PMID: 15837373.

Article14. Vilacoba E, Almuzara M, Gulone L, Traglia GM, Figueroa SA, Sly G, et al. 2013; Emergence and spread of plasmid-borne tet(B)::ISCR2 in minocycline-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 57:651–4. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01751-12. PMID: 23147737. PMCID: PMC3535920.15. Yoon EJ, Oh Y, Jeong SH. 2020; Development of tigecycline resistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 147 via AcrAB overproduction mediated by replacement of the ramA promoter. Ann Lab Med. 40:15–20. DOI: 10.3343/alm.2020.40.1.15. PMID: 31432634. PMCID: PMC6713659.16. Wang L, Liu D, Lv Y, Cui L, Li Y, Li T, et al. 2019; Novel plasmid-mediated tet(X5) gene conferring resistance to tigecycline, eravacycline, and omadacycline in a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 64:e01326–19. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01326-19. PMID: 31611352. PMCID: PMC7187588.

Article17. Lin Z, Pu Z, Xu G, Bai B, Chen Z, Sun X, et al. 2020; Omadacycline efficacy against Enterococcus faecalis isolated in China: in vitro activity, heteroresistance, and resistance mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 64:e02097–19. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.02097-19. PMID: 31871086. PMCID: PMC7038293.

Article18. CLSI. 2010. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing for infrequently isolated of fastidious bacteria: approved guideline. CLSI M45eA2. 2nd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;Wayne, PA:19. Yao W, Xu G, Bai B, Wang H, Deng M, Zheng J, et al. 2018; In vitro-induced erythromycin resistance facilitates cross-resistance to the novel fluoroketolide, solithromycin, in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett . 365. DOI: 10.1093/femsle/fny116. PMID: 29733362.20. Collins JR, Arredondo A, Roa A, Valdez Y, León R, Blanc V. 2016; Periodontal pathogens and tetracycline resistance genes in subgingival biofilm of periodontally healthy and diseased dominican adults. Clin Oral Investig. 20:349–56. DOI: 10.1007/s00784-015-1516-2. PMID: 26121972. PMCID: PMC4762914.

Article21. Villedieu A, Diaz-Torres ML, Hunt N, McnabR , Spratt DA, Wilson M, et al. 2003; Prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes in oral bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 47:878–82. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.878-882.2003. PMID: 12604515. PMCID: PMC149302.

Article22. Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Rhomberg PR, Flamm RK. 2017; Surveillance of omadacycline activity against clinical isolates from a global collection (North America, Europe, Latin America, Asia-western pacific), 2010-2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 61:e00018–17. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00018-17. PMID: 28223386. PMCID: PMC5404553.

Article23. Gonullu N, Catal F, Kucukbasmaci O, Ozdemir S, Torun MM, Berkiten R. 2009; Comparison of in vitro activities of tigecycline with other antimicrobial agents against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in two university hospitals in Istanbul, Turkey. Chemotherapy. 55:161–7. DOI: 10.1159/000214144. PMID: 19390189.24. Zheng JX, Lin ZW, Sun X, Lin WH, Chen Z, Wu Y, et al. 2018; Overexpression of OqxAB and MacAB efflux pumps contributes to eravacycline resistance and heteroresistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg Microbes Infect. 7:139. DOI: 10.1038/s41426-018-0141-y. PMID: 30068997. PMCID: PMC6070572.25. Fiedler S, Bender JK, Klare I, Halbedel S, Grohmann E, Szewzyk U, et al. 2016; Tigecycline resistance in clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium is mediated by an upregulation of plasmid-encoded tetracycline determinants tet(L) and tet(M). J Antimicrob Chemother. 71:871–81. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkv420. PMID: 26682961.26. Connell SR, Trieber CA, Stelzl U, Einfeldt E, Taylor DE, Nierhaus KH. 2002; The tetracycline resistance protein Tet(o) perturbs the conformation of the ribosomal decoding centre. Mol Microbiol. 45:1463–72. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03115.x. PMID: 12354218.27. Honeyman L, Ismail M, Nelson ML, Bhatia B, Bowser TE, Chen J, et al. 2015; Structure-activity relationship of the aminomethylcyclines and the discovery of omadacycline. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59:7044–53. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01536-15. PMID: 26349824. PMCID: PMC4604364.

Article28. Heidrich CG, Mitova S, Schedlbauer A, Connell SR, Fucini P, Steenbergen JN, et al. 2016; The novel aminomethylcycline omadacycline has high specificity for the primary tetracycline-binding site on the bacterial ribosome. Antibiotics (Basel). 5:32. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics5040032. PMID: 27669321. PMCID: PMC5187513.

Article29. Grossman TH. 2016; Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6:a025387. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025387. PMID: 26989065. PMCID: PMC4817740.

Article30. Bauer G, Berens C, Projan SJ, Hillen W. 2004; Comparison of tetracycline and tigecycline binding to ribosomes mapped by dimethylsulphate and drug-directed Fe2+ cleavage of 16S rRNA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 53:592–9. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkh125. PMID: 14985271.31. Lupien A, Gingras H, Leprohon P, Ouellette M. 2015; Induced tigecycline resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants reveals mutations in ribosomal proteins and rRNA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 70:2973–80. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkv211. PMID: 26183184.32. Bai B, Lin Z, Pu Z, Xu G, Zhang F, Chen Z, et al. 2019; In vitro activity and heteroresistance of omadacycline against clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates from China reveal the impact of omadacycline susceptibility by branched-chain amino acid transport system II carrier protein, Na/Pi cotransporter family protein, and fibronectin-binding protein. Front Microbiol. 10:2546. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02546. PMID: 31787948. PMCID: PMC6856048.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Nasopharyngeal Colonization of Moraxella catarrhalis in Young Korean Children

- In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Cefditoren pivoxil, an Oral Cephalosporin, against Major Clinical Isolates

- In vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Cefcapene against Clinical Isolates

- In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Cefroxadine, an Oral Cephalosporin, Against Major Clinical Isolates

- In Vitro Activities of Gatifloxacin against Bacteria isolated from Respiratory Specimens of Patients of University Hospitals in Korea