Challenges and Limitations of Strategies to Promote Therapeutic Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Cell-Based Cardiac Repair

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Department of Biomedicine & Health Sciences, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Chemistry, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 5Cell Death Disease Research Center, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2512460

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0518

Abstract

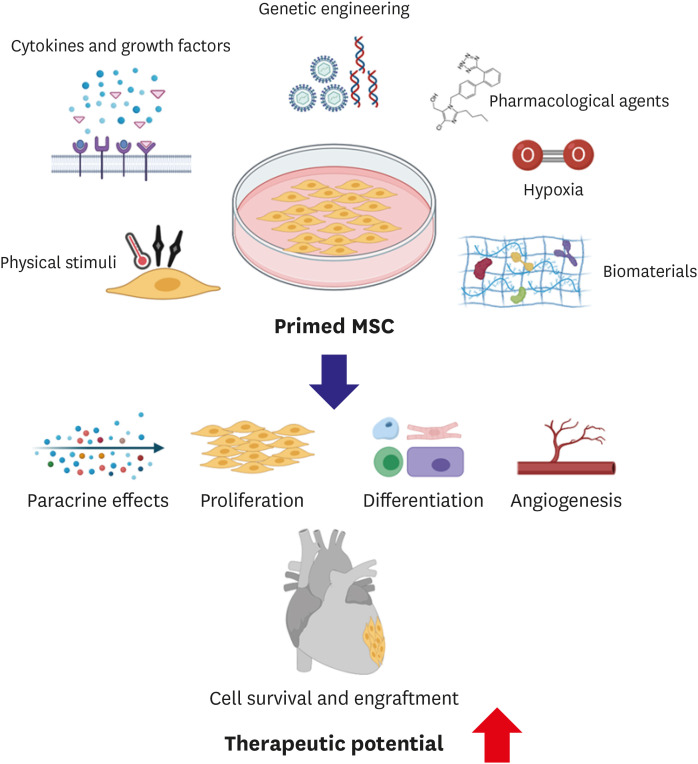

- Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a population of adult stem cells residing in many tissues, mainly bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord. Due to the safety and availability of standard procedures and protocols for isolation, culturing, and characterization of these cells, MSCs have emerged as one of the most promising sources for cell-based cardiac regenerative therapy. Once transplanted into a damaged heart, MSCs release paracrine factors that nurture the injured area, prevent further adverse cardiac remodeling, and mediate tissue repair along with vasculature. Numerous preclinical studies applying MSCs have provided significant benefits following myocardial infarction. Despite promising results from preclinical studies using animal models, MSCs are not up to the mark for human clinical trials. As a result, various approaches have been considered to promote the therapeutic potency of MSCs, such as genetic engineering, physical treatments, growth factor, and pharmacological agents. Each strategy has targeted one or multi-potentials of MSCs. In this review, we will describe diverse approaches that have been developed to promote the therapeutic potential of MSCs for cardiac regenerative therapy. Particularly, we will discuss major characteristics of individual strategy to enhance therapeutic efficacy of MSCs including scientific principles, advantages, limitations, and improving factors. This article also will briefly introduce recent novel approaches that MSCs enhanced therapeutic potentials of other cells for cardiac repair.

Figure

Cited by 5 articles

-

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Infants from the Perspective of Cardiomyocyte Maturation

Heeyoung Seok, Jin-Hee Oh

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(9):733-751. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0153.Role of miRNA-324-5p-Modified Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Post-Myocardial Infarction Repair

Zhou Ji, Chan Wang, Qing Tong

Int J Stem Cells. 2021;14(3):298-309. doi: 10.15283/ijsc21025.Stem Cell and Exosome Therapy in Pulmonary Hypertension

Seyeon Oh, Ji-Hye Jung, Kyung-Jin Ahn, Albert Youngwoo Jang, Kyunghee Byun, Phillip C. Yang, Wook-Jin Chung

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(2):110-122. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0191.Cardiovascular Regeneration via Stem Cells and Direct Reprogramming: A Review

Choon-Soo Lee, Joonoh Kim, Hyun-Jai Cho, Hyo-Soo Kim

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(5):341-353. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0005.The Gut-Heart Axis: Updated Review for The Roles of Microbiome in Cardiovascular Health

Thi Van Anh Bui, Hyesoo Hwangbo, Yimin Lai, Seok Beom Hong, Yeon-Jik Choi, Hun-Jun Park, Kiwon Ban

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(8):499-518. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0048.

Reference

-

1. Tanai E, Frantz S. Pathophysiology of heart failure. Compr Physiol. 2015; 6:187–214. PMID: 26756631.

Article2. Jiang Y, Park P, Hong SM, Ban K. Maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells: current strategies and limitations. Mol Cells. 2018; 41:613–621. PMID: 29890820.3. Sunagawa G, Horvath DJ, Karimov JH, Moazami N, Fukamachi K. Future prospects for the total artificial heart. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2016; 13:191–201. PMID: 26732059.

Article4. Miyagawa S, Fukushima S, Imanishi Y, et al. Building a new treatment for heart failure-transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cells into the heart. Curr Gene Ther. 2016; 16:5–13. PMID: 26785736.

Article5. Anastasiadis K, Antonitsis P, Argiriadou H, et al. Hybrid approach of ventricular assist device and autologous bone marrow stem cells implantation in end-stage ischemic heart failure enhances myocardial reperfusion. J Transl Med. 2011; 9:12. PMID: 21247486.

Article7. Friedenstein AJ, Gorskaja JF, Kulagina NN. Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse hematopoietic organs. Exp Hematol. 1976; 4:267–274. PMID: 976387.8. Wickham MQ, Erickson GR, Gimble JM, Vail TP, Guilak F. Multipotent stromal cells derived from the infrapatellar fat pad of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003; 412:196–212.

Article9. Fong CY, Chak LL, Biswas A, et al. Human Wharton's jelly stem cells have unique transcriptome profiles compared to human embryonic stem cells and other mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2011; 7:1–16. PMID: 20602182.

Article10. Morgan JE, Partridge TA. Muscle satellite cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003; 35:1151–1156. PMID: 12757751.

Article11. Shen D, Cheng K, Marbán E. Dose-dependent functional benefit of human cardiosphere transplantation in mice with acute myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2012; 16:2112–2116. PMID: 22225626.

Article12. Menasché P, Vanneaux V. Stem cells for the treatment of heart failure. Curr Res Transl Med. 2016; 64:97–106. PMID: 27316393.

Article13. Ghiroldi A, Piccoli M, Cirillo F, et al. Cell-based therapies for cardiac regeneration: a comprehensive review of past and ongoing strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19:3194.

Article14. Williams AR, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011; 109:923–940. PMID: 21960725.15. Mirotsou M, Zhang Z, Deb A, et al. Secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) is the key Akt-mesenchymal stem cell-released paracrine factor mediating myocardial survival and repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104:1643–1648. PMID: 17251350.

Article16. Pittenger MF, Martin BJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and their potential as cardiac therapeutics. Circ Res. 2004; 95:9–20. PMID: 15242981.

Article17. Kim J, Shapiro L, Flynn A. The clinical application of mesenchymal stem cells and cardiac stem cells as a therapy for cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 151:8–15. PMID: 25709098.

Article18. Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007; 25:2739–2749. PMID: 17656645.

Article19. Wang X, Zhen L, Miao H, et al. Concomitant retrograde coronary venous infusion of basic fibroblast growth factor enhances engraftment and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Theranostics. 2015; 5:995–1006. PMID: 26155315.

Article20. Li X, Zhao H, Qi C, Zeng Y, Xu F, Du Y. Direct intercellular communications dominate the interaction between adipose-derived MSCs and myofibroblasts against cardiac fibrosis. Protein Cell. 2015; 6:735–745. PMID: 26271509.

Article21. Miteva K, Pappritz K, El-Shafeey M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells modulate monocytes trafficking in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017; 6:1249–1261. PMID: 28186704.

Article22. Yu B, Kim HW, Gong M, et al. Exosomes secreted from GATA-4 overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells serve as a reservoir of anti-apoptotic microRNAs for cardioprotection. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 182:349–360. PMID: 25590961.

Article23. Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005; 11:367–368. PMID: 15812508.

Article24. Davani S, Marandin A, Mersin N, et al. Mesenchymal progenitor cells differentiate into an endothelial phenotype, enhance vascular density, and improve heart function in a rat cellular cardiomyoplasty model. Circulation. 2003; 108(Suppl 1):II253–II258. PMID: 12970242.

Article25. Guo Y, Yu Y, Hu S, Chen Y, Shen Z. The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2020; 11:349. PMID: 32393744.

Article26. Pandey AC, Lancaster JJ, Harris DT, Goldman S, Juneman E. Cellular therapeutics for heart failure: focus on mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017; 2017:9640108. PMID: 29391871.

Article27. Liao S, Zhang Y, Ting S, et al. Potent immunomodulation and angiogenic effects of mesenchymal stem cells versus cardiomyocytes derived from pluripotent stem cells for treatment of heart failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019; 10:78. PMID: 30845990.

Article28. Korf-Klingebiel M, Kempf T, Sauer T, et al. Bone marrow cells are a rich source of growth factors and cytokines: implications for cell therapy trials after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2008; 29:2851–2858. PMID: 18953051.

Article29. Quevedo HC, Hatzistergos KE, Oskouei BN, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells restore cardiac function in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy via trilineage differentiating capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106:14022–14027. PMID: 19666564.

Article30. Noiseux N, Gnecchi M, Lopez-Ilasaca M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing Akt dramatically repair infarcted myocardium and improve cardiac function despite infrequent cellular fusion or differentiation. Mol Ther. 2006; 14:840–850. PMID: 16965940.

Article31. Zhao JJ, Liu XC, Kong F, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial function in a swine model of acute myocardial infarction. Mol Med Rep. 2014; 10:1448–1454. PMID: 25060678.

Article32. Chen SL, Fang WW, Ye F, et al. Effect on left ventricular function of intracoronary transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 94:92–95. PMID: 15219514.

Article33. Lee JW, Lee SH, Youn YJ, et al. A randomized, open-label, multicenter trial for the safety and efficacy of adult mesenchymal stem cells after acute myocardial infarction. J Korean Med Sci. 2014; 29:23–31. PMID: 24431901.

Article34. Mathiasen AB, Qayyum AA, Jørgensen E, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell treatment in patients with severe ischaemic heart failure: a randomized placebo-controlled trial (MSC-HF trial). Eur Heart J. 2015; 36:1744–1753. PMID: 25926562.

Article35. Xiao W, Guo S, Gao C, et al. A randomized comparative study on the efficacy of intracoronary infusion of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells and mesenchymal stem cells in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Int Heart J. 2017; 58:238–244. PMID: 28190794.

Article36. Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2004; 364:141–148. PMID: 15246726.

Article37. Gyöngyösi M, Wojakowski W, Lemarchand P, et al. Meta-Analysis of Cell-based CaRdiac stUdiEs (ACCRUE) in patients with acute myocardial infarction based on individual patient data. Circ Res. 2015; 116:1346–1360. PMID: 25700037.

Article38. Yu H, Lu K, Zhu J, Wang J. Stem cell therapy for ischemic heart diseases. Br Med Bull. 2017; 121:135–154. PMID: 28164211.

Article39. Karantalis V, DiFede DL, Gerstenblith G, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells produce concordant improvements in regional function, tissue perfusion, and fibrotic burden when administered to patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: the Prospective Randomized Study of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery (PROMETHEUS) trial. Circ Res. 2014; 114:1302–1310. PMID: 24565698.40. Guijarro D, Lebrin M, Lairez O, et al. Intramyocardial transplantation of mesenchymal stromal cells for chronic myocardial ischemia and impaired left ventricular function: Results of the MESAMI 1 pilot trial. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 209:258–265. PMID: 26901787.

Article41. Florea V, Rieger AC, DiFede DL, et al. Dose comparison study of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (The TRIDENT Study). Circ Res. 2017; 121:1279–1290. PMID: 28923793.

Article42. Li W, Ma N, Ong LL, et al. Bcl-2 engineered MSCs inhibited apoptosis and improved heart function. Stem Cells. 2007; 25:2118–2127. PMID: 17478584.

Article43. Najafi R, Sharifi AM. Deferoxamine preconditioning potentiates mesenchymal stem cell homing in vitro and in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013; 13:959–972. PMID: 23536977.44. Hu C, Li L. Preconditioning influences mesenchymal stem cell properties in vitro and in vivo . J Cell Mol Med. 2018; 22:1428–1442. PMID: 29392844.45. Yin K, Zhu R, Wang S, Zhao RC. Low-level laser effect on proliferation, migration, and antiapoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2017; 26:762–775. PMID: 28178868.

Article46. Urnukhsaikhan E, Cho H, Mishig-Ochir T, Seo YK, Park JK. Pulsed electromagnetic fields promote survival and neuronal differentiation of human BM-MSCs. Life Sci. 2016; 151:130–138. PMID: 26898125.

Article47. Wang S, Zhang C, Niyazi S, et al. A novel cytoprotective peptide protects mesenchymal stem cells against mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis induced by starvation via Nrf2/Sirt3/FoxO3a pathway. J Transl Med. 2017; 15:33. PMID: 28202079.

Article48. Kim KJ, Joe YA, Kim MK, et al. Silica nanoparticles increase human adipose tissue-derived stem cell proliferation through ERK1/2 activation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015; 10:2261–2272. PMID: 25848249.

Article49. Fierro FA, O'Neal AJ, Beegle JR, et al. Hypoxic pre-conditioning increases the infiltration of endothelial cells into scaffolds for dermal regeneration pre-seeded with mesenchymal stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015; 3:68. PMID: 26579521.

Article50. Matsui T, Tao J, del Monte F, et al. Akt activation preserves cardiac function and prevents injury after transient cardiac ischemia in vivo. Circulation. 2001; 104:330–335. PMID: 11457753.51. Mangi AA, Noiseux N, Kong D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with Akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nat Med. 2003; 9:1195–1201. PMID: 12910262.

Article52. Jiang S, Haider HK, Idris NM, Salim A, Ashraf M. Supportive interaction between cell survival signaling and angiocompetent factors enhances donor cell survival and promotes angiomyogenesis for cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2006; 99:776–784. PMID: 16960098.

Article53. Shujia J, Haider HK, Idris NM, Lu G, Ashraf M. Stable therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell-based multiple gene delivery for cardiac repair. Cardiovasc Res. 2008; 77:525–533. PMID: 18032392.

Article54. Wang J, Yang H, Hu X, et al. Dobutamine-mediated heme oxygenase-1 induction via PI3K and p38 MAPK inhibits high mobility group box 1 protein release and attenuates rat myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo . J Surg Res. 2013; 183:509–516. PMID: 23531454.55. Takamiya R, Hung CC, Hall SR, et al. High-mobility group box 1 contributes to lethality of endotoxemia in heme oxygenase-1-deficient mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009; 41:129–135. PMID: 19097991.

Article56. Tang YL, Tang Y, Zhang YC, Qian K, Shen L, Phillips MI. Improved graft mesenchymal stem cell survival in ischemic heart with a hypoxia-regulated heme oxygenase-1 vector. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:1339–1350. PMID: 16198853.

Article57. Jiang YB, Zhang XL, Tang YL, et al. Effects of heme oxygenase-1 gene modulated mesenchymal stem cells on vasculogenesis in ischemic swine hearts. Chin Med J (Engl). 2011; 124:401–407. PMID: 21362341.58. De Becker A, Riet IV. Homing and migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: how to improve the efficacy of cell therapy? World J Stem Cells. 2016; 8:73–87. PMID: 27022438.59. Huang J, Zhang Z, Guo J, et al. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing CCR1 increases cell viability, migration, engraftment, and capillary density in the injured myocardium. Circ Res. 2010; 106:1753–1762. PMID: 20378860.

Article60. Song SW, Chang W, Song BW, et al. Integrin-linked kinase is required in hypoxic mesenchymal stem cells for strengthening cell adhesion to ischemic myocardium. Stem Cells. 2009; 27:1358–1365. PMID: 19489098.

Article61. Liu L, Gao J, Yuan Y, Chang Q, Liao Y, Lu F. Hypoxia preconditioned human adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells enhance angiogenic potential via secretion of increased VEGF and bFGF. Cell Biol Int. 2013; 37:551–560. PMID: 23505143.

Article62. Hu X, Yu SP, Fraser JL, et al. Transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells improves infarcted heart function via enhanced survival of implanted cells and angiogenesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008; 135:799–808. PMID: 18374759.

Article63. Chacko SM, Ahmed S, Selvendiran K, Kuppusamy ML, Khan M, Kuppusamy P. Hypoxic preconditioning induces the expression of prosurvival and proangiogenic markers in mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010; 299:C1562–70. PMID: 20861473.

Article64. Hu X, Xu Y, Zhong Z, et al. A large-scale investigation of hypoxia-preconditioned allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for myocardial repair in nonhuman primates: paracrine activity without remuscularization. Circ Res. 2016; 118:970–983. PMID: 26838793.65. Rosová I, Dao M, Capoccia B, Link D, Nolta JA. Hypoxic preconditioning results in increased motility and improved therapeutic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008; 26:2173–2182. PMID: 18511601.

Article66. Hu X, Wei L, Taylor TM, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell migration via Kv2.1 channel and FAK activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011; 301:C362–72. PMID: 21562308.

Article67. Han YS, Lee JH, Yoon YM, Yun CW, Noh H, Lee SH. Hypoxia-induced expression of cellular prion protein improves the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016; 7:e2395. PMID: 27711081.

Article68. Fehrer C, Brunauer R, Laschober G, et al. Reduced oxygen tension attenuates differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells and prolongs their lifespan. Aging Cell. 2007; 6:745–757. PMID: 17925003.

Article69. Estrada JC, Albo C, Benguría A, et al. Culture of human mesenchymal stem cells at low oxygen tension improves growth and genetic stability by activating glycolysis. Cell Death Differ. 2012; 19:743–755. PMID: 22139129.

Article70. Singec I, Snyder EY. Inflammation as a matchmaker: revisiting cell fusion. Nat Cell Biol. 2008; 10:503–505. PMID: 18454127.

Article71. Zhu Z, Gan X, Fan H, Yu H. Mechanical stretch endows mesenchymal stem cells stronger angiogenic and anti-apoptotic capacities via NFκB activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015; 468:601–605. PMID: 26545780.

Article72. Gorin C, Rochefort GY, Bascetin R, et al. Priming dental pulp stem cells with fibroblast growth factor-2 increases angiogenesis of implanted tissue-engineered constructs through hepatocyte growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016; 5:392–404. PMID: 26798059.

Article73. Liu X, Duan B, Cheng Z, et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 axis modulates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis, migration and cytokine secretion. Protein Cell. 2011; 2:845–854. PMID: 22058039.

Article74. Herrmann JL, Wang Y, Abarbanell AM, Weil BR, Tan J, Meldrum DR. Preconditioning mesenchymal stem cells with transforming growth factor-alpha improves mesenchymal stem cell-mediated cardioprotection. Shock. 2010; 33:24–30. PMID: 19996917.

Article75. Cunningham CJ, Redondo-Castro E, Allan SM. The therapeutic potential of the mesenchymal stem cell secretome in ischaemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018; 38:1276–1292. PMID: 29768965.

Article76. Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, et al. Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006; 24:386–398. PMID: 16123384.77. François M, Romieu-Mourez R, Li M, Galipeau J. Human MSC suppression correlates with cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and bystander M2 macrophage differentiation. Mol Ther. 2012; 20:187–195. PMID: 21934657.

Article78. Noronha NC, Mizukami A, Caliári-Oliveira C, et al. Priming approaches to improve the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019; 10:131. PMID: 31046833.

Article79. Chinnadurai R, Copland IB, Patel SR, Galipeau J. IDO-independent suppression of T cell effector function by IFN-γ-licensed human mesenchymal stromal cells. J Immunol. 2014; 192:1491–1501. PMID: 24403533.

Article80. Rovira Gonzalez YI, Lynch PJ, Thompson EE, Stultz BG, Hursh DA. In vitro cytokine licensing induces persistent permissive chromatin at the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase promoter. Cytotherapy. 2016; 18:1114–1128. PMID: 27421739.81. Tu Z, Li Q, Bu H, Lin F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit complement activation by secreting factor H. Stem Cells Dev. 2010; 19:1803–1809. PMID: 20163251.

Article82. Redondo-Castro E, Cunningham C, Miller J, et al. Interleukin-1 primes human mesenchymal stem cells towards an anti-inflammatory and pro-trophic phenotype in vitro . Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017; 8:79. PMID: 28412968.

Article83. Wisel S, Khan M, Kuppusamy ML, et al. Pharmacological preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells with trimetazidine (1-[2,3,4-trimethoxybenzyl]piperazine) protects hypoxic cells against oxidative stress and enhances recovery of myocardial function in infarcted heart through Bcl-2 expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009; 329:543–550. PMID: 19218529.

Article84. Bhatti FU, Mehmood A, Latief N, et al. Vitamin E protects rat mesenchymal stem cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in vitro and improves their therapeutic potential in surgically-induced rat model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017; 25:321–331. PMID: 27693502.85. Song L, Yang YJ, Dong QT, et al. Atorvastatin enhance efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells treatment for swine myocardial infarction via activation of nitric oxide synthase. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e65702. PMID: 23741509.

Article86. Noiseux N, Borie M, Desnoyers A, et al. Preconditioning of stem cells by oxytocin to improve their therapeutic potential. Endocrinology. 2012; 153:5361–5372. PMID: 23024264.

Article87. Sun X, Fang B, Zhao X, Zhang G, Ma H. Preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells by sevoflurane to improve their therapeutic potential. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e90667. PMID: 24599264.

Article88. Numasawa Y, Kimura T, Miyoshi S, et al. Treatment of human mesenchymal stem cells with angiotensin receptor blocker improved efficiency of cardiomyogenic transdifferentiation and improved cardiac function via angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2011; 29:1405–1414. PMID: 21755575.

Article89. Li M, Yu L, She T, et al. Astragaloside IV attenuates Toll-like receptor 4 expression via NF-κB pathway under high glucose condition in mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012; 696:203–209. PMID: 23041150.

Article90. Lee J, Shin MS, Kim MO, et al. Apple ethanol extract promotes proliferation of human adult stem cells, which involves the regenerative potential of stem cells. Nutr Res. 2016; 36:925–936. PMID: 27632912.

Article91. Yang Y, Choi H, Seon M, Cho D, Bang SI. LL-37 stimulates the functions of adipose-derived stromal/stem cells via early growth response 1 and the MAPK pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016; 7:58. PMID: 27095351.

Article92. Yu Y, Wei N, Stanford C, Schmidt T, Hong L. In vitro effects of RU486 on proliferation and differentiation capabilities of human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Steroids. 2012; 77:132–137. PMID: 22093480.93. Zhang LY, Xue HG, Chen JY, Chai W, Ni M. Genistein induces adipogenic differentiation in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and suppresses their osteogenic potential by upregulating PPARγ. Exp Ther Med. 2016; 11:1853–1858. PMID: 27168816.

Article94. Liu XB, Wang JA, Ji XY, Yu SP, Wei L. Preconditioning of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by prolyl hydroxylase inhibition enhances cell survival and angiogenesis in vitro and after transplantation into the ischemic heart of rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014; 5:111. PMID: 25257482.95. Peyvandi AA, Abbaszadeh HA, Roozbahany NA, et al. Deferoxamine promotes mesenchymal stem cell homing in noise-induced injured cochlea through PI3K/AKT pathway. Cell Prolif. 2018; 51:e12434. PMID: 29341316.

Article96. Fujisawa K, Takami T, Okada S, et al. Analysis of metabolomic changes in mesenchymal stem cells on treatment with desferrioxamine as a hypoxia mimetic compared with hypoxic conditions. Stem Cells. 2018; 36:1226–1236. PMID: 29577517.

Article97. Hafizi M, Hajarizadeh A, Atashi A, et al. Nanochelating based nanocomplex, GFc7, improves quality and quantity of human mesenchymal stem cells during in vitro expansion. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015; 6:226. PMID: 26597909.

Article98. Li Z, Xu X, Wang W, et al. Modulation of the mesenchymal stem cell migration capacity via preconditioning with topographic microstructure. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2017; 67:267–278. PMID: 28869459.

Article99. Ciocci M, Cacciotti I, Seliktar D, Melino S. Injectable silk fibroin hydrogels functionalized with microspheres as adult stem cells-carrier systems. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018; 108:960–971. PMID: 29113887.

Article100. Wahl EA, Schenck TL, Machens HG, Balmayor ER. VEGF released by deferoxamine preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells seeded on collagen-GAG substrates enhances neovascularization. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:36879. PMID: 27830734.

Article101. Sart S, Agathos SN, Li Y, Ma T. Regulation of mesenchymal stem cell 3D microenvironment: from macro to microfluidic bioreactors. Biotechnol J. 2016; 11:43–57. PMID: 26696441.

Article102. Maia FR, Fonseca KB, Rodrigues G, Granja PL, Barrias CC. Matrix-driven formation of mesenchymal stem cell-extracellular matrix microtissues on soft alginate hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2014; 10:3197–3208. PMID: 24607421.

Article103. Grayson WL, Ma T, Bunnell B. Human mesenchymal stem cells tissue development in 3D PET matrices. Biotechnol Prog. 2004; 20:905–912. PMID: 15176898.

Article104. Tsai AC, Liu Y, Ma T. Expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells in fibrous bed bioreactor. Biochem Eng J. 2016; 108:51–57.

Article105. Wang Q, Li X, Wang Q, Xie J, Xie C, Fu X. Heat shock pretreatment improves mesenchymal stem cell viability by heat shock proteins and autophagy to prevent cisplatin-induced granulosa cell apoptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019; 10:348. PMID: 31771642.

Article106. Moloney TC, Hoban DB, Barry FP, Howard L, Dowd E. Kinetics of thermally induced heat shock protein 27 and 70 expression by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Protein Sci. 2012; 21:904–909. PMID: 22505291.

Article107. Park BW, Jung SH, Das S, et al. In vivo priming of human mesenchymal stem cells with hepatocyte growth factor-engineered mesenchymal stem cells promotes therapeutic potential for cardiac repair. Sci Adv. 2020; 6:eaay6994. PMID: 32284967.108. Nakamura T, Mizuno S. The discovery of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its significance for cell biology, life sciences and clinical medicine. Proc Jpn Acad, Ser B, Phys Biol Sci. 2010; 86:588–610.

Article109. Xu RX, Chen X, Chen JH, Han Y, Han BM. Mesenchymal stem cells promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro through hypoxia-induced paracrine mechanisms. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009; 36:176–180. PMID: 18785984.110. Hahn JY, Cho HJ, Kang HJ, et al. Pre-treatment of mesenchymal stem cells with a combination of growth factors enhances gap junction formation, cytoprotective effect on cardiomyocytes, and therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51:933–943. PMID: 18308163.

Article111. Liang T, Zhu L, Gao W, et al. Coculture of endothelial progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells enhanced their proliferation and angiogenesis through PDGF and Notch signaling. FEBS Open Bio. 2017; 7:1722–1736.

Article112. Wu L, Prins HJ, Helder MN, van Blitterswijk CA, Karperien M. Trophic effects of mesenchymal stem cells in chondrocyte co-cultures are independent of culture conditions and cell sources. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012; 18:1542–1551. PMID: 22429306.

Article113. Lazar-Karsten P, Dorn I, Meyer G, Lindner U, Driller B, Schlenke P. The influence of extracellular matrix proteins and mesenchymal stem cells on erythropoietic cell maturation. Vox Sang. 2011; 101:65–76. PMID: 21175667.

Article114. Wang Y, Tu W, Lou Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells regulate the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells through Notch signaling. Cell Biol Int. 2009; 33:1173–1179. PMID: 19706332.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Adipose Tissue - Adequate, Accessible Regenerative Material

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Liver Disease: Present and Perspectives

- Advanced Research on Stem Cell Therapy for Hepatic Diseases: Potential Implications of a Placenta-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell-based Strategy

- Treatment of Articular Cartilage Injury Using Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation for Ischemic Diseases: Mechanisms and Challenges