Lab Med Online.

2020 Oct;10(4):276-282. 10.47429/lmo.2020.10.4.276.

Turnaround Time (TAT) Setting Status of 30 Domestic Clinical Laboratories and Consideration for Improvement and Management of TAT

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, KoreA

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Inje University, Busan, Korea

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Asan, Korea

- KMID: 2512266

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.47429/lmo.2020.10.4.276

Abstract

- Background

Turnaround time (TAT) is a major quality control indicator and can be defined differently depending on the starting point in the examination process. To determine effective TAT management plan, we investigated the status of TAT management in clinical laboratories in Korea.

Methods

A questionnaire was developed using Google web pages and a questionnaire survey was conducted at 30 clinical laboratories in laboratory medicine from September 1 to 11 in 2018. Questions were developed regarding management time, starting point standards, management goals, most problematic stages of delayed TAT, clinical measures, and shortening barriers for investigation.

Results

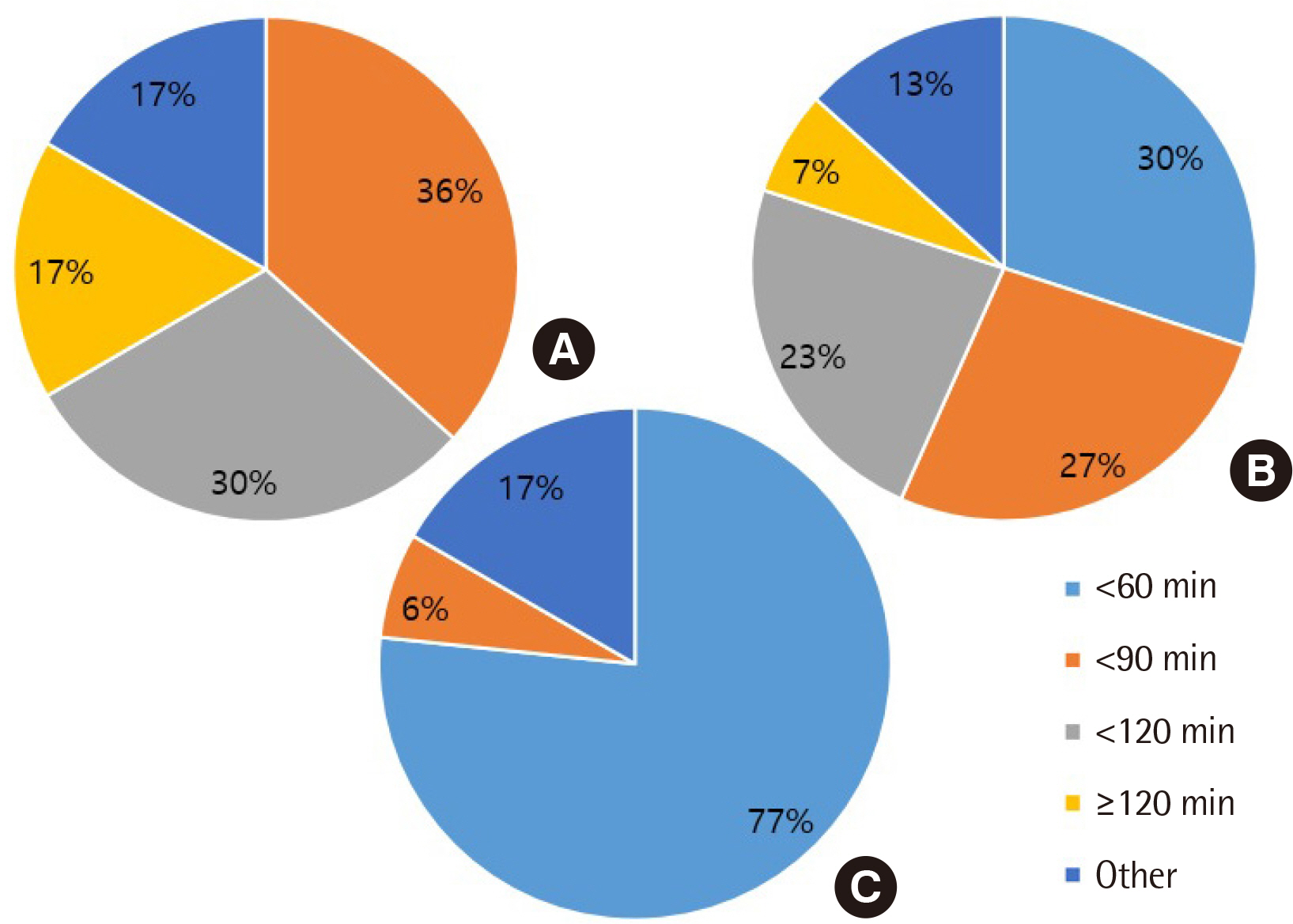

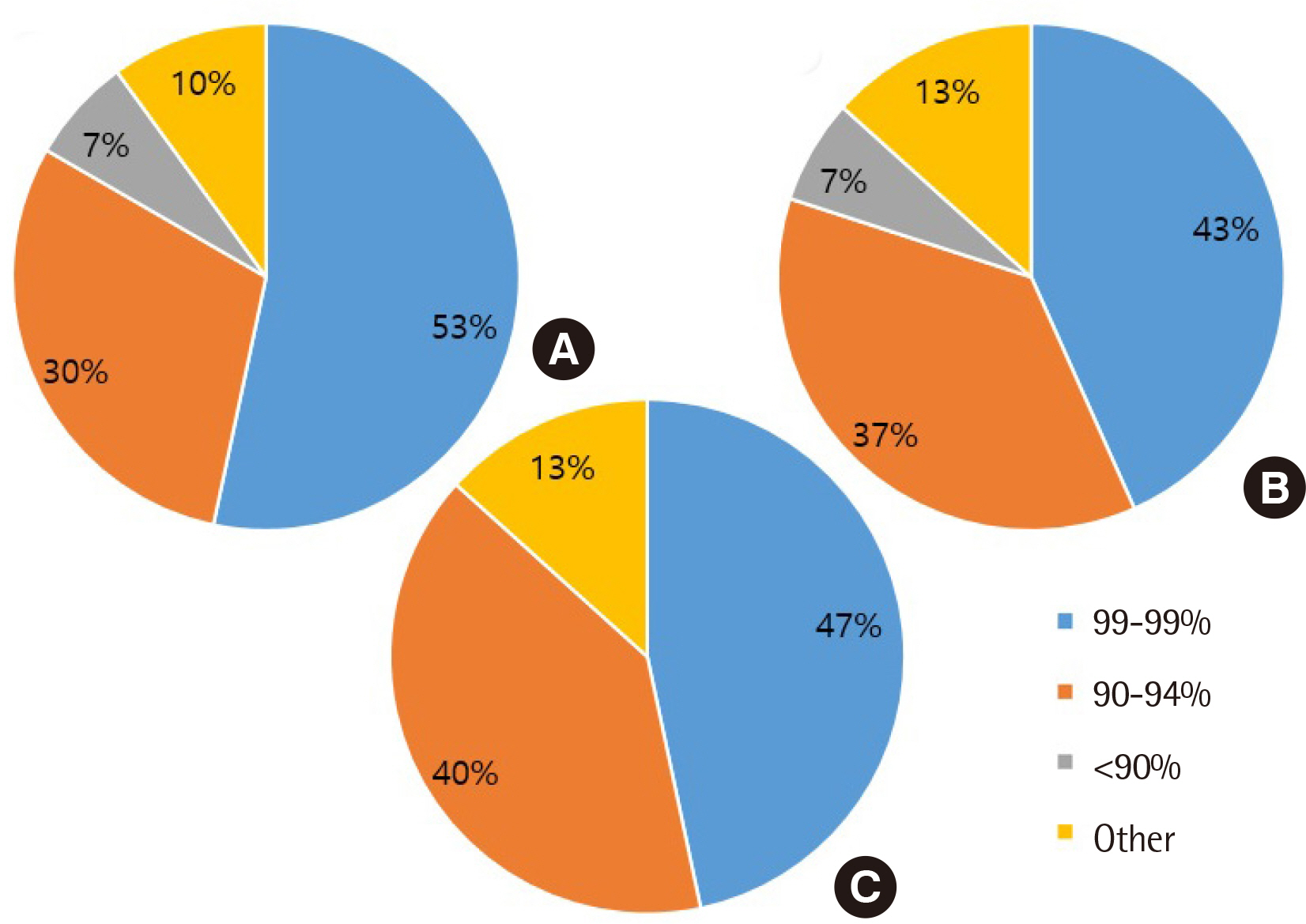

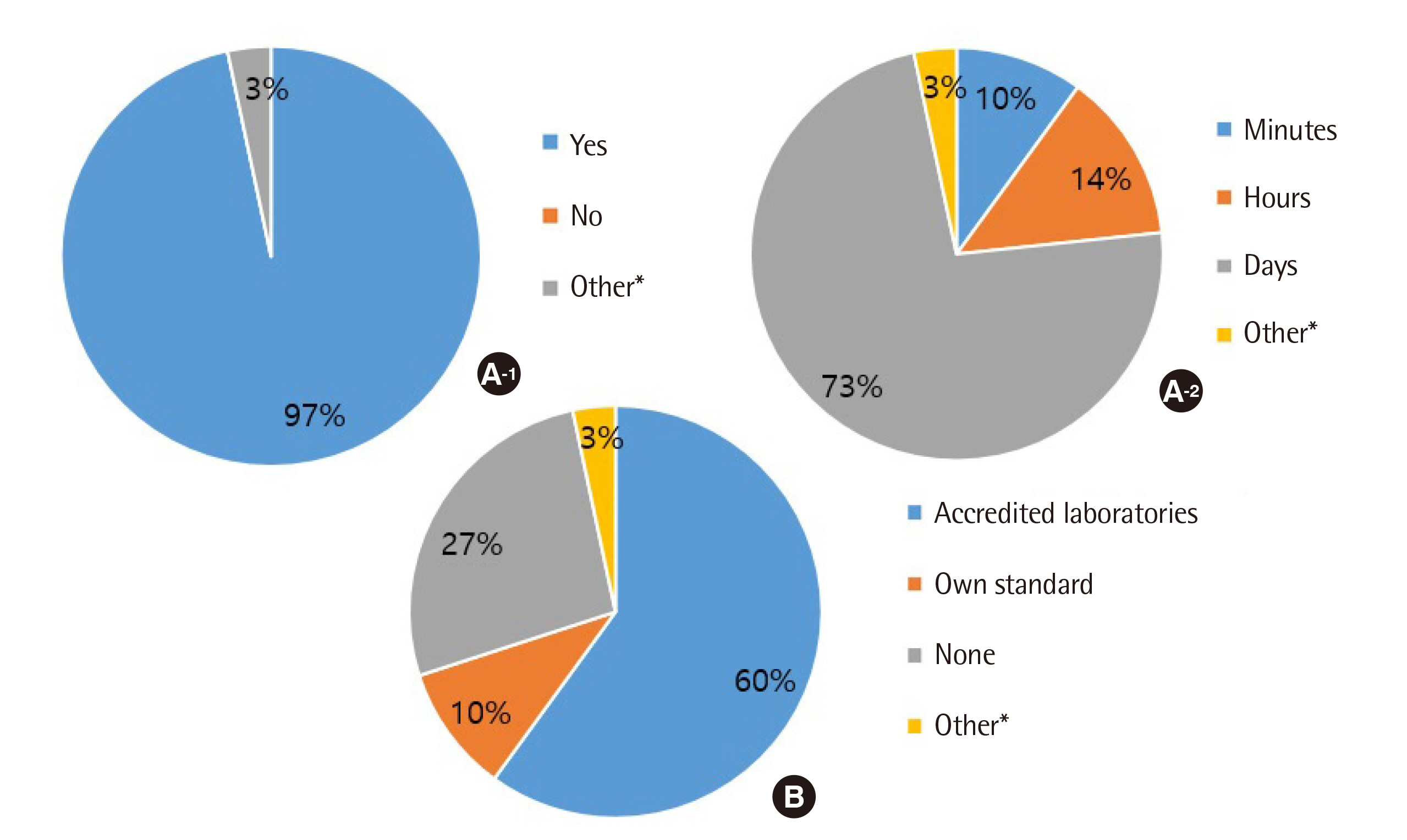

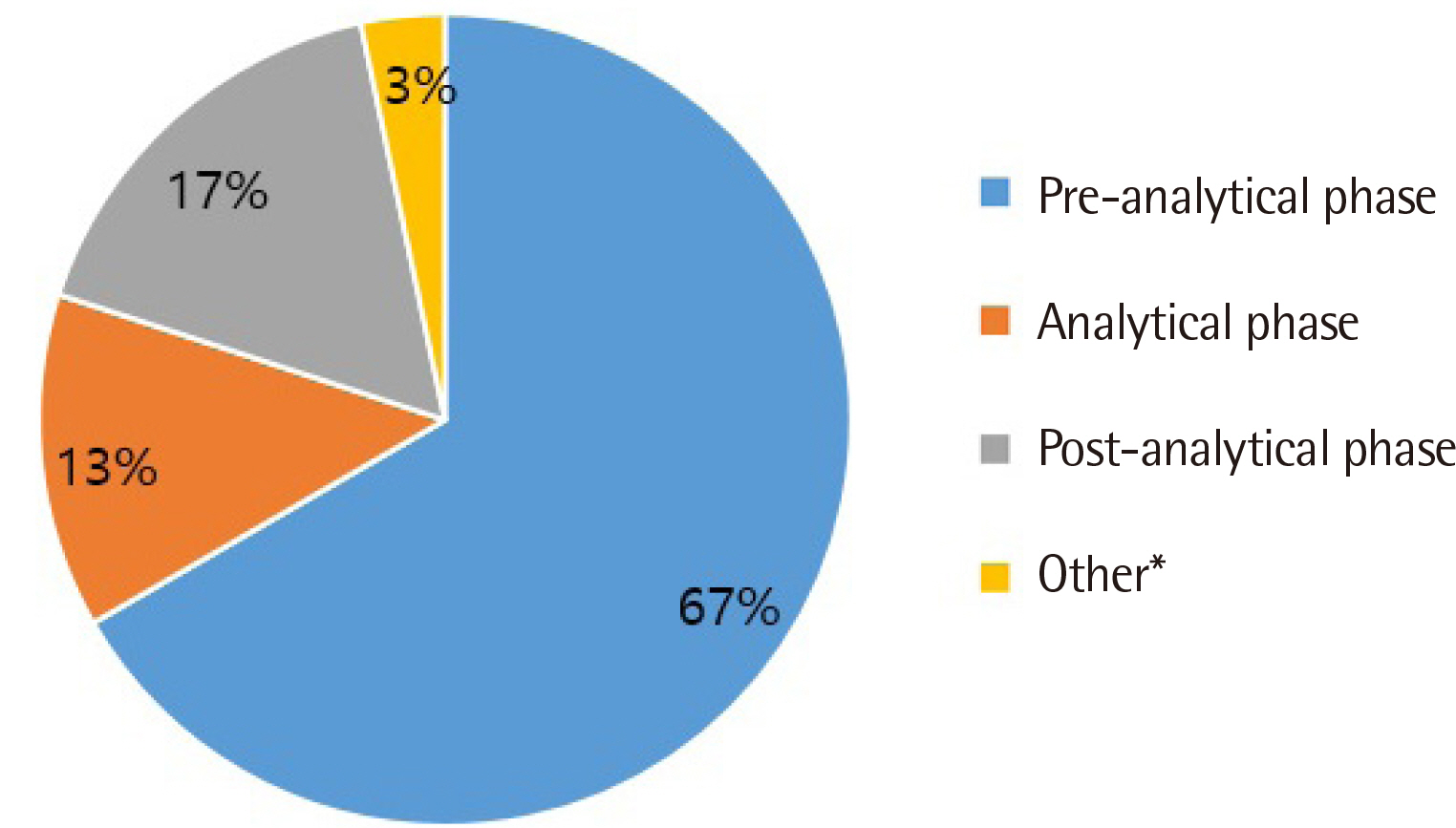

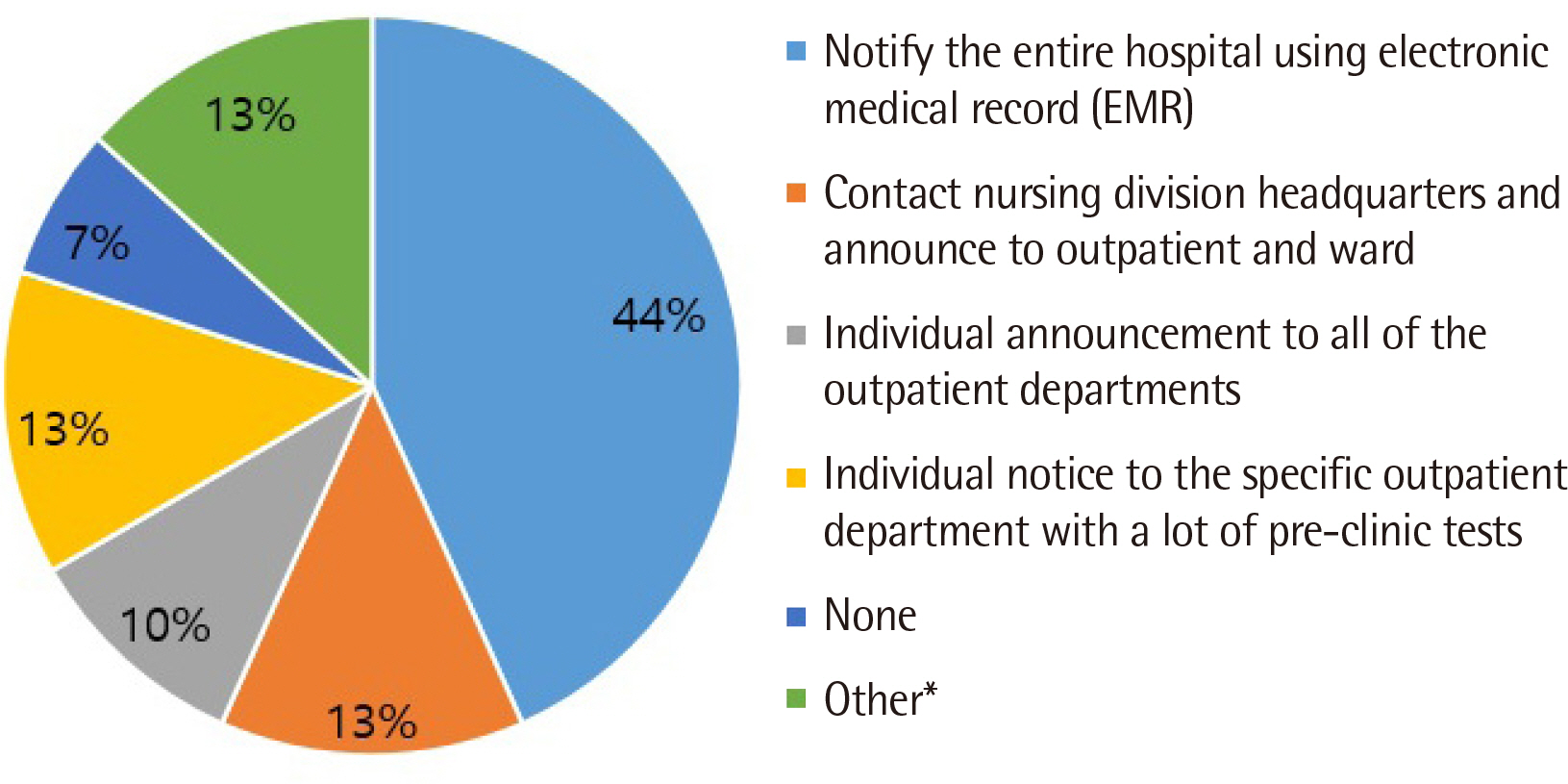

All clinical laboratories requested to undertake the survey completed the questionnaire (response rate 100%, 30/30) and answered that they were setting and managing TAT for all tests. Many laboratories (33%) set the TAT starting point as the reception stage, prior to commencing centrifugation. Of the surveyed laboratories, 37% achieved a TAT of 120 min or more for general tests, 27% met the TAT of 90 min for pre-clinic tests, and 77% met the TAT of 60 min for completion of stat tests. Most laboratories (67%) reported that the most delayed stage was pre-analysis, and 50% reported that the greatest obstacle to shortening TAT was the ratio of stat and pre-clinic tests to general tests.

Conclusions

The laboratories participating in this survey set a TAT based on various criteria and were performing management for TAT improvement. The results of this study can be used as basic data to guide efficient TAT management.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hawkins RC. 2007; Laboratory turnaround time. Clin Biochem Rev. 28:179–94. DOI: 10.1515/cclm.2002.068. PMID: 32969071.2. Chung H-J, Lee W, Chun S, Park H-I, Min W-K. 2009; Analysis of turnaround time by subdividing three phases for outpatient chemistry specimens. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 39:144–9. PMID: 19429800.3. Novis DA, Walsh MK, Dale JC, Howanitz PJ. 2004; Continuous monitoring of stat and routine outlier turnaround times: two College of American Pathologists Q-Tracks monitors in 291 hospitals. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 128:621–6. DOI: 10.1043/1543-2165(2004)128<621:CMOSAR>2.0.CO;2. PMID: 15163240.

Article4. Steindel SJ, Novis DA. 1999; Using outlier events to monitor test turnaround time: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study in 496 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 123:607–14. DOI: 10.1043/0003-9985(1999)123<0607:UOETMT>2.0.CO;2. PMID: 10388917.5. Dhatt G, Manna J, Bishawi B, Chetty D, Al Sheiban A, James D. 2008; Impact of a satellite laboratory on turnaround times for the emergency department. Clin Chem Lab Med. 46:1464–7. DOI: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.290. PMID: 18844503.

Article6. Sorita A, Patterson A, Landazuri P, De-Lin S, Fischer C, Husk G, et al. 2014; The feasibility and impact of midnight routine blood draws on laboratory orders and processing time. Am J Clin Pathol. 141:805–10. DOI: 10.1309/AJCPPL8KFH3KFHNV. PMID: 24838324.

Article7. Arslan FD, Karakoyun I, Basok BI, Aksit MZ, Baysoy A, Ozturk YK, et al. 2017; The local clinical validation of a new lithium heparin tube with a barrier: BD Vacutainer® Barricor LH Plasma tube. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 27:030706. DOI: 10.11613/BM.2017.030706. PMID: 28900369. PMCID: PMC5575652.

Article8. Cadamuro J, Mrazek C, Leichtle AB, Kipman U, Felder TK, Wiedemann H, et al. 2018; Influence of centrifugation conditions on the results of 77 routine clinical chemistry analytes using standard vacuum blood collection tubes and the new BD-Barricor tubes. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 28:10704. DOI: 10.11613/BM.2018.010704. PMID: 29187797. PMCID: PMC5701775.

Article9. Compeau S, Howlett M, Matchett S, Shea J, Fraser J, McCloskey R, et al. 2016; Does elimination of a laboratory sample clotting stage requirement reduce overall turnaround times for emergency department stat biochemical testing? Cureus. 8:e819. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.819. PMID: 27843737. PMCID: PMC5096945.

Article10. Ko DH, Won D, Jeong TD, Lee W, Chun S, Min WK. 2015; Comparison of red blood cell hemolysis using plasma and serum separation tubes for outpatient specimens. Ann Lab Med. 35:194–7. DOI: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.2.194. PMID: 25729720. PMCID: PMC4330168.

Article11. Fernandes CM, Worster A, Eva K, Hill S, McCallum C. 2006; Pneumatic tube delivery system for blood samples reduces turnaround times without affecting sample quality. J Emerg Nurs. 32:139–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.11.013. PMID: 16580476.

Article12. World Health Organization. Use of anticoagulants in diagnostic laboratory investigations. 2nd Revision. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/65957/WHO_DIL_LAB_99.1_REV.2.pdf?.sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Updated on Jan 2002.13. Lou AH, Elnenaei MO, Sadek I, Thompson S, Crocker BD, Nassar BA. 2017; Multiple pre-and post-analytical lean approaches to the improvement of the laboratory turnaround time in a large core laboratory. Clin Biochem. 50:864–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.04.019. PMID: 28457964.14. Fournier JE, Northryp V, Clark C, Fraser J, Howlett M, Atkinson P, et al. 2018; Evaluation of BD Vacutainer® Barricor™ blood collection tubes for routine chemistry testing on a Roche Cobas® 8000 Platform. Clin Biochem. 58:94–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.06.002. PMID: 29885310.15. Laboratory Medicine Foundation. 2019. Clinical laboratory accreditation checklist for clinical chemistry. Laboratory Medicine Foundation;Seoul:16. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010. Development and use of quality indicators for process improvement and monitoring of laboratory quality; Approved guideline. CLSI guideline QMS12-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;Wayne, PA:17. Steindel SJ, Howanitz PJ. 2001; Physician satisfaction and emergency department laboratory test turnaround time: observations based on College of American Pathologists Q-Probes studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 125:863–71.18. Stotler BA, Kratz A. 2012; Determination of turnaround time in the clinical laboratory: "accessioning-to-result" time does not always accurately reflect laboratory performance. Am J Clin Pathol. 138:724–9. DOI: 10.1309/AJCPYHBT9OQRM8DX. PMID: 23086774.19. McKillop PA, Auld P. 2017; National turnaround time survey: professional consensus standards for optimal performance and thresholds considered to compromise efficient and effective clinical management. Ann Clin Biochem. 54:158–64. DOI: 10.1177/0004563216651887. PMID: 27166313.

Article20. Goswami B, Singh B, Chawla R, Gupta VK, Mallika V. 2010; Turn around time (TAT) as a benchmark of laboratory performance. Indian J Clin Biochem. 25:376–9. DOI: 10.1007/s12291-010-0056-4. PMID: 21966108. PMCID: PMC2994570.

Article21. Acute phase hospital Accreditation. 2018. Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation. http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0101vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=040101&CONT_SEQ=345528&page=1.22. Kaushik N, Khangulov VS, O'Hara M, Arnaout R. 2018; Reduction in laboratory turnaround time decreases emergency room length of stay. Open Access Emerg Med. 10:37–45. DOI: 10.2147/OAEM.S155988. PMID: 29719423. PMCID: PMC5916382.

Article23. Holland LL, Smith LL, Blick KE. 2005; Reducing laboratory turnaround time outliers can reduce emergency department patient length of stay: an 11-hospital study. Am J Clin Pathol. 124:672–4. DOI: 10.1309/E9QPVQ6G2FBVMJ3B. PMID: 16203280.24. Howanitz PJ. 2005; Errors in laboratory medicine: practical lessons to improve patient safety. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 129:1252–61. DOI: 10.1043/1543-2165(2005)129[1252:EILMPL]2.0.CO;2. PMID: 16196513.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of Turnaround Time for Packed Red Blood Cell Delivery by Laboratory Information System: Shortening of Turnaround Time Through Quality Improvement Program

- Efficiency of an Automated Reception and Turnaround Time Management System for the Phlebotomy Room

- Turnaround times of blood issue analyzed by a computer system

- p53-mediated Inhibitory Mechanism on HIV-1 Tat is Likely to be Associated with Tat-Phosphorylation

- Application of Predictive Modelling to Improve the Discharge Process in Hospitals