J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Jan;36(2):e16. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e16.

Clinical Pathway for Emergency Brain Surgery during COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Clinical Outcomes

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2510589

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e16

Abstract

- Background

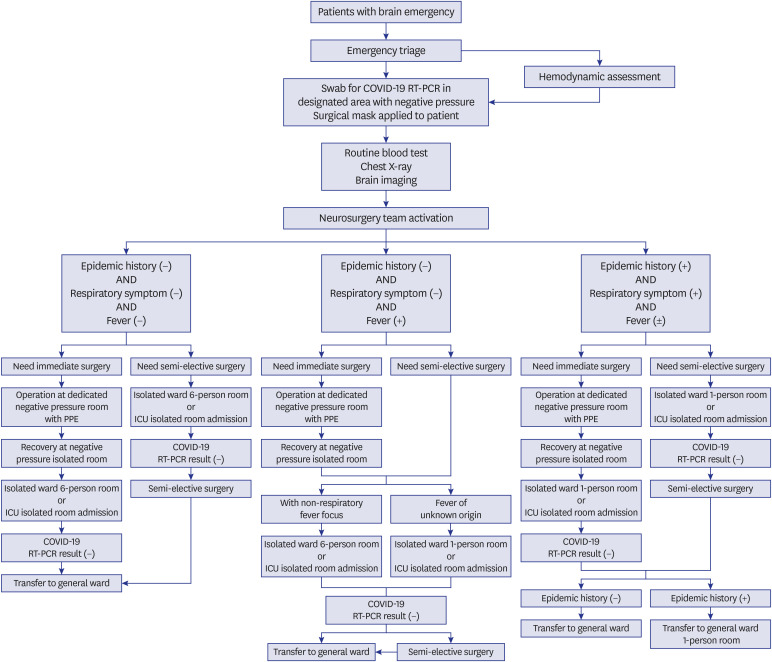

One of the challenges neurosurgeons are facing in the global public health crisis caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is to balance COVID-19 screening with timely surgery. We described a clinical pathway for patients who needed emergency brain surgery and determined whether differences in the surgery preparation process caused by COVID-19 screening affected clinical outcomes.

Methods

During the COVID-19 period, patients in need of emergency brain surgery in our institution were managed using a novel standardized pathway designed for COVID-19 screening. We conducted a retrospective review of patients who were hospitalized through the emergency room and underwent emergency brain surgery. A total of 32 patients who underwent emergency brain surgery from February 1 to June 30, 2020 were included in the COVID-19 group, and 65 patients who underwent surgery from February 1 to June 30, 2019 were included in the pre-COVID-19 group. The baseline characteristics, disease severity indicators, time intervals of emergency processes, and clinical outcomes of the two groups were compared. Subgroup analysis was performed between the immediate surgery group and the semi-elective surgery group during the COVID-19 period.

Results

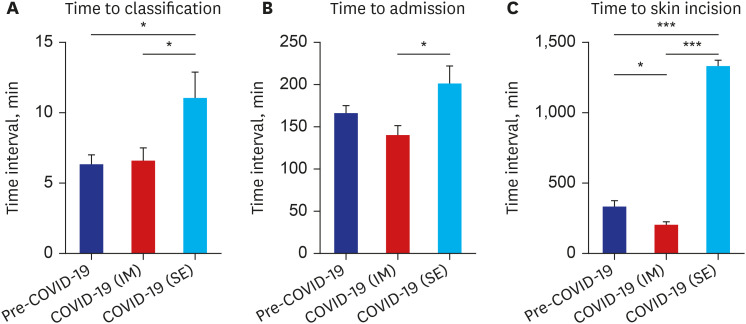

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics and severity indicators between the pre-COVID-19 group and COVID-19 group. The time interval to skin incision was significantly increased in the COVID-19 group (P = 0.027). However, there were no significant differences in the clinical outcomes between the two groups. In subgroup comparison, the time interval to skin incision was shorter in the immediate surgery group during the COVID-19 period compared with the pre-COVID-19 group (P = 0.040). The screening process did not significantly increase the time interval to classification and admission for immediate surgery. The time interval to surgery initiation was longer in the COVID-19 period due to the increased time interval in the semi-elective surgery group (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

We proposed a clinical pathway for the preoperative screening of COVID-19 in patients requiring emergency brain surgery. No significant differences were observed in the clinical outcomes before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The protocol we described showed acceptable results during this pandemic.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020; 55(3):105924. PMID: 32081636.

Article2. Lai CC, Wang CY, Wang YH, Hsueh SC, Ko WC, Hsueh PR. Global epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): disease incidence, daily cumulative index, mortality, and their association with country healthcare resources and economic status. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020; 55(4):105946. PMID: 32199877.

Article3. Kandel N, Chungong S, Omaar A, Xing J. Health security capacities in the context of COVID-19 outbreak: an analysis of International Health Regulations annual report data from 182 countries. Lancet. 2020; 395(10229):1047–1053. PMID: 32199075.

Article4. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(8):727–733. PMID: 31978945.

Article5. Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020; 76:71–76. PMID: 32112977.

Article6. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Updated 2020. Accessed September 2, 2020. https://covid19.who.int/.7. Coronavirus disease-19, Republic of Korea. Updated 2020. Accessed September 2, 2020. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/.8. Schirmer CM, Ringer AJ, Arthur AS, Binning MJ, Fox WC, James RF, et al. Delayed presentation of acute ischemic strokes during the COVID-19 crisis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020; 12(7):639–642. PMID: 32467244.

Article9. Ansari A. Neurosurgical practice during coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020; 15(3):469–470. PMID: 33145193.

Article10. Massey PA, McClary K, Zhang AS, Savoie FH, Barton RS. Orthopaedic surgical selection and inpatient paradigms during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020; 28(11):436–450. PMID: 32304401.

Article11. Gok AFK, Eryılmaz M, Ozmen MM, Alimoglu O, Ertekin C, Kurtoglu MH. Recommendations for trauma and emergency general surgery practice during COVID-19 pandemic. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2020; 26(3):335–342. PMID: 32394416.

Article12. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020; 91(1):157–160. PMID: 32191675.13. Kwon YS, Park SH, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Hyun MR, Kim HA, et al. Screening clinic for coronavirus disease 2019 to prevent intrahospital spread in Daegu, Korea: a single-center report. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(26):e246. PMID: 32627444.

Article14. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020; 323(13):1239–1242. PMID: 32091533.15. Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, Gordon D, Hartl R, Newell DW, et al. Guidelines for the surgical management of traumatic brain injury author group. Appendix II: evaluation of relevant computed tomographic scan findings. Neurosurgery. 2006; 58(Suppl 3):S2-62.16. Kim JE, Ko SB, Kang HS, Seo DH, Park SQ, Sheen SH, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the medical and surgical management of primary intracerebral hemorrhage in Korea. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014; 56(3):175–187. PMID: 25368758.

Article17. Nuñez JH, Sallent A, Lakhani K, Guerra-Farfan E, Vidal N, Ekhtiari S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an emergency traumatology service: experience at a tertiary trauma centre in Spain. Injury. 2020; 51(7):1414–1418. PMID: 32405089.

Article18. Randelli PS, Compagnoni R. Management of orthopaedic and traumatology patients during the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in northern Italy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020; 28(6):1683–1689. PMID: 32335697.

Article19. Meng Y, Leng K, Shan L, Guo M, Zhou J, Tian Q, et al. A clinical pathway for pre-operative screening of COVID-19 and its influence on clinical outcome in patients with traumatic fractures. Int Orthop. 2020; 44(8):1549–1555. PMID: 32468202.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-hospital mortality in patients admitted through the emergency department

- Characteristics and clinical outcomes of older patients with trauma visiting the emergency department before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A level 1 trauma center cohort study

- Impact of COVID-19 on the care of acute appendicitis: a single-center experience in Korea

- Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Colorectal Cancer

- The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and chronic diseases