J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Jan;36(1):e10. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e10.

Etiological Distribution and Morphological Patterns of Granulomatous Pleurisy in a Tuberculosis-prevalent Country

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 2Department of Clinical Pathology, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 3Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2510378

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e10

Abstract

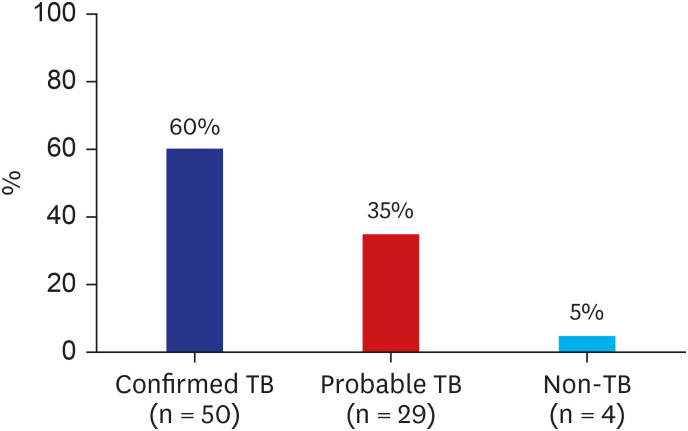

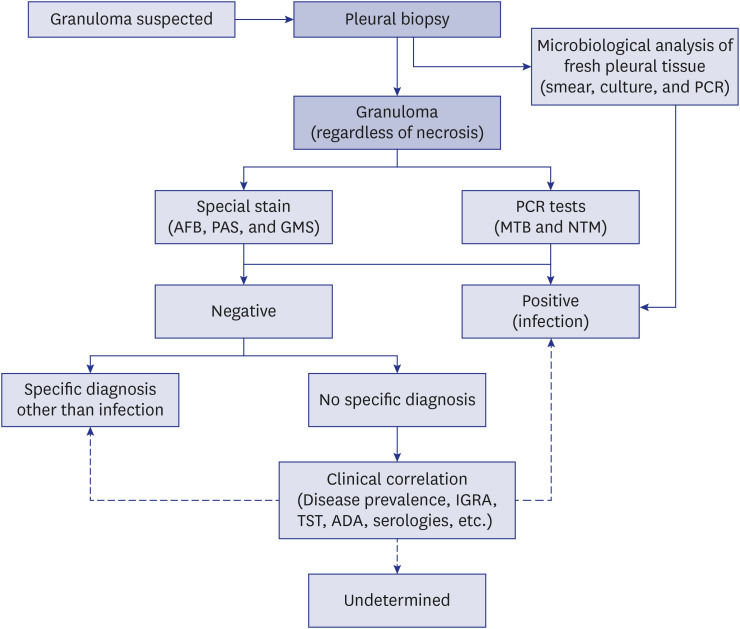

- The cause of epithelioid granulomatous inflammation varies widely depending on the affected organ, geographic region, and whether the granulomas morphologically contain necrosis. Compared with other organs, the etiological distribution and morphological patterns of pleural epithelioid granulomas have rarely been investigated. We evaluated the final etiologies and morphological patterns of pleural epithelioid granulomatous inflammation in a tuberculosis (TB)-prevalent country. Of 83 patients with pleural granulomas, 50 (60.2%) had confirmed TB pleurisy (TB-P) and 29 (34.9%) had probable TBP. Four patients (4.8%) with non-TB-P were diagnosed. With the exception of microbiological results, there was no significant difference in clinical characteristics and granuloma patterns between the confirmed TB-P and non-TB-P groups, or between patients with confirmed and probable TB-Ps. These findings suggest that most pleural granulomatous inflammation (95.2%) was attributable to TB-P in TB-endemic areas and that the granuloma patterns contributed little to the prediction of final diagnosis compared with other organs.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Woodard BH, Rosenberg SI, Farnham R, Adams DO. Incidence and nature of primary granulomatous inflammation in surgically removed material. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982; 6(2):119–129. PMID: 7102892.

Article2. Mukhopadhyay S, Farver CF, Vaszar LT, Dempsey OJ, Popper HH, Mani H, et al. Causes of pulmonary granulomas: a retrospective study of 500 cases from seven countries. J Clin Pathol. 2012; 65(1):51–57. PMID: 22011444.

Article3. Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017; 7:1–12. PMID: 31723695.

Article4. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2019. Updated 2020. Accessed August 12, 2020. http://www.who.int/tb/data.5. WHO revised definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis. Euro Surveill. 2013; 18:20455. PMID: 23611033.6. Yeon JH, Seong H, Hur H, Park Y, Kim YA, Park YS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of latent tuberculosis among Korean healthcare workers using whole-blood interferon-gamma release assay. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1):10113. PMID: 29973678.

Article7. Judson MA. The clinical features of sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015; 49(1):63–78. PMID: 25274450.

Article8. Huggins JT, Doelken P, Sahn SA, King L, Judson MA. Pleural effusions in a series of 181 outpatients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2006; 129(6):1599–1604. PMID: 16778281.

Article9. Park S, Jo KW, Lee SD, Kim WS, Shim TS. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of pleural effusions in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Respir Med. 2017; 133:36–41. PMID: 29173447.

Article10. Naito M, Maekura T, Kurahara Y, Tahara M, Ikegami N, Kimura Y, et al. Clinical features of nontuberculous mycobacterial pleurisy: a review of 12 cases. Intern Med. 2018; 57(1):13–16. PMID: 29033435.

Article11. Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the series "Pathology for the clinician" edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev. 2007; 26(145):170012.12. Akhter N, Sumalani KK, Chawla D, Ahmed Rizvi N. Comparison between the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert MTB/Rif assay and culture for pleural tuberculosis using tissue biopsy. ERJ Open Res. 2019; 5(3):00065-2019. PMID: 31579677.

Article13. Che N, Yang X, Liu Z, Li K, Chen X. Rapid detection of cell-free mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in tuberculous pleural effusion. J Clin Microbiol. 2017; 55(5):1526–1532. PMID: 28275073.

Article14. Choi H, Chon HR, Kim K, Kim S, Oh KJ, Jeong SH, et al. Clinical and laboratory differences between lymphocyte- and neutrophil-predominant pleural tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2016; 11(10):e0165428. PMID: 27788218.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Tuberculous Pleurisy: An Update

- Statistical Clinical Observation on Lung Diseases from 1972 to 1976

- Soluble Interleukin-2 Receptor(sIL-2R) Levels in Patients Tuberculous Pleurisy VS Nontuberculous Pleurisy

- Tuberculous Pleurisy: Clinical Characteristics of Primary and Reactivation Disease

- Diagnostic Efficacy of Adenosine Deaminase Isoenzyme in Tuberculous Pleurisy