Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2021 Jan;25(1):69-77. 10.4196/kjpp.2021.25.1.69.

The effect of adenosine triphosphate on propofol-induced myopathy in rats: a biochemical and histopathological evaluation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Balikesir Ataturk City Hospital Anesthesiology and Reanimation Clinic, Balikesir 10010, Turkey

- 2Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Erzurum Nenehatun Maternity Hospital, Erzurum 25000, Turkey

- 3Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Faculty of Medicine, Ataturk University, Erzurum 25000, Turkey

- 4Departments of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Faculty of Medicine, Erzincan Binali Yildirim University, Erzincan 24100, Turkey

- 5Departments of Medical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Erzincan Binali Yildirim University, Erzincan 24100, Turkey

- 6Departments of Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Erzincan Binali Yildirim University, Erzincan 24100, Turkey

- 7Departments of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine, Erzincan Binali Yildirim University, Erzincan 24100, Turkey

- 8Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Erzincan Binali Yildirim University, Erzincan 24100, Turkey

- 9Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Erzincan Binali Yildirim University, Erzincan 24100, Turkey

- KMID: 2509656

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2021.25.1.69

Abstract

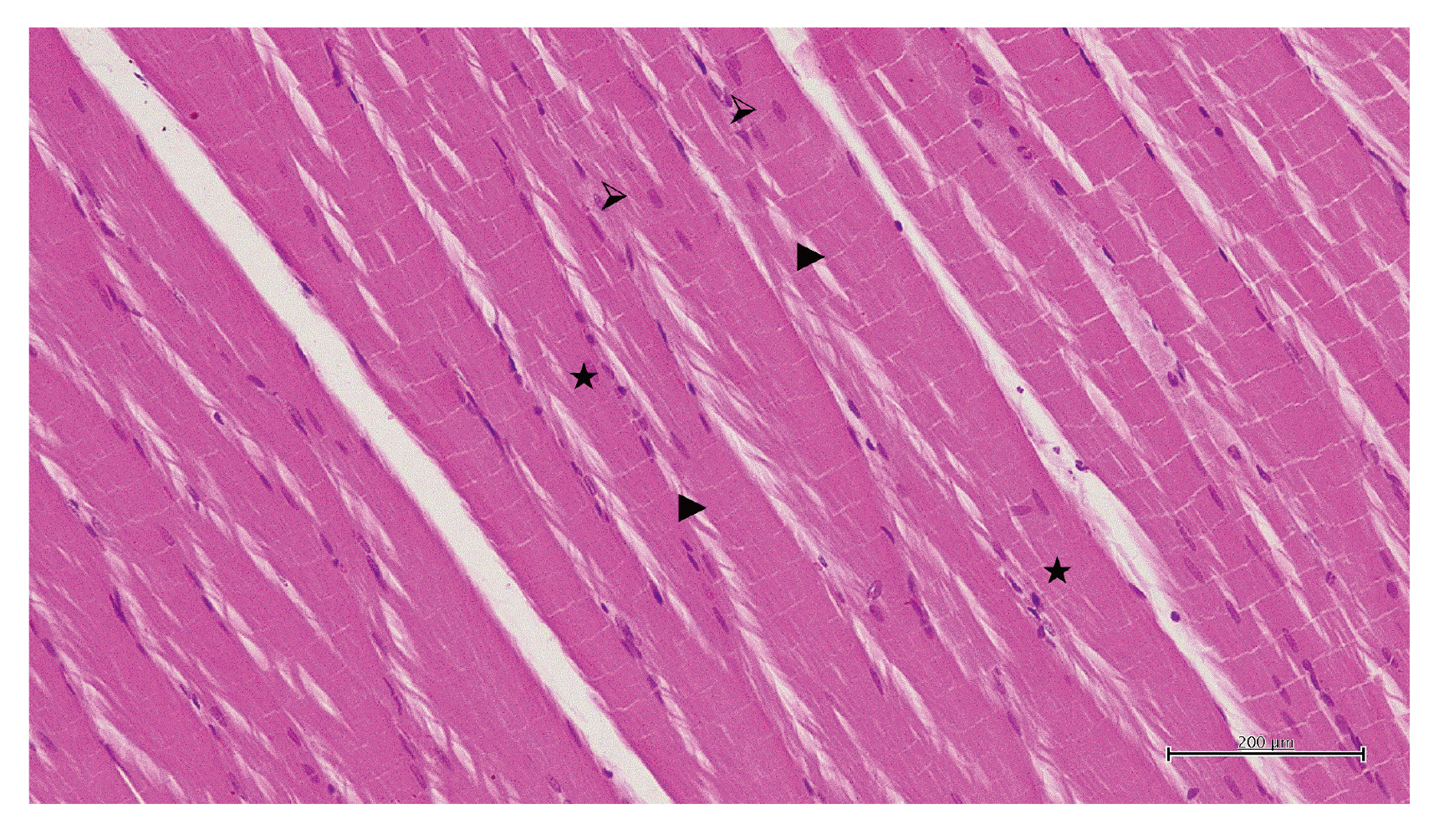

- Propofol infusion syndrome characterized by rhabdomyolysis, metabolic acidosis, kidney, and heart failure has been reported in long-term propofol use for sedation. It has been reported that intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is reduced in rhabdomyolysis. The study aims to investigate the protective effect of ATP against possible skeletal muscle damage of propofol in albino Wistar male rats biochemically and histopathologically. PA-50 (n = 6) and PA-100 (n = 6) groups of animals was injected intraperitoneally to 4 mg/kg ATP. An equal volume (0.5 ml) of distilled water was administered intraperitoneally to the P-50, P-100, and HG groups. One hour after the administration of ATP and distilled water, 50 mg/kg propofol was injected intraperitoneally to the P-50 and PA-50 groups. This procedure was repeated once a day for 30 days. The dose of 100 mg/kg propofol was injected intraperitoneally to the P-100 and PA-100 groups. This procedure was performed three times with an interval of 1 days. Our experimental results showed that propofol increased serum CK, CK-MB, creatinine, BUN, TP I, ALT, AST levels, and muscle tissue MDA levels at 100 mg/kg compared to 50 mg/kg and decreased tGSH levels. At a dose of 100 mg/ kg, propofol caused more severe histopathological damage compared to 50 mg/ kg. It was found that ATP prevented propofol-induced muscle damage and organ dysfunction at a dose of 50 mg/kg at a higher level compared to 100 mg/kg. ATP may be useful in the treatment of propofol-induced rhabdomyolysis and multiple organ damage.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Trevor AJ, Miller RD. Katzung BG, editor. 1998. General anesthetic. Basic and clinical pharmacology. 7th ed. Appleton & Lange;Stamford (CT): p. 409–423.2. Sear JW. 1987; Toxicity of i.v. anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth. 59:24–45. DOI: 10.1093/bja/59.1.24. PMID: 3548787.3. Krajčová A, Løvsletten NG, Waldauf P, Frič V, Elkalaf M, Urban T, Anděl M, Trnka J, Thoresen GH, Duška F. 2018; Effects of propofol on cellular bioenergetics in human skeletal muscle cells. Crit Care Med. 46:e206–e212. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002875. PMID: 29240609.

Article4. Secor T, Safadi AO, Gunderson S. Gunderson S, editor. 2020. Propofol toxicity. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing;Treasure Island (FL):5. Hemphill S, McMenamin L, Bellamy MC, Hopkins PM. 2019; Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured literature review and analysis of published case reports. Br J Anaesth. 122:448–459. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.12.025. PMID: 30857601. PMCID: PMC6435842.

Article6. Michel-Macías C, Morales-Barquet DA, Reyes-Palomino AM, Machuca-Vaca JA, Orozco-Guillén A. 2018; Single dose of propofol causing propofol infusion syndrome in a newborn. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2018:omy023. DOI: 10.1093/omcr/omy023. PMID: 29942532. PMCID: PMC6007798.

Article7. Tezcan AH, Öterkuş M, Dönmez İ, Öztürk Ö, Yavuzekinci Z. 2018; A mild type propofol infusion syndrome presentation in critical care. Kafkas J Med Sci. 8:61–63. DOI: 10.5505/kjms.2018.32154.

Article8. Tezcan AH, Ozturk O, Adali Y, Erdem E, Yagmurdur H. 2016; Abstract PR462: the effects of N-acetylcysteine in a propofol infusion syndrome model in rats. Anesth Analg. 123(3 Suppl 2):586. DOI: 10.1213/01.ane.0000492849.43769.9e.9. Khan FY. 2009; Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Neth J Med. 67:272–283. PMID: 19841484.10. Ypsilantis P, Politou M, Mikroulis D, Lambropoulou M, Bougioukas I, Theodoridis G, Tsigalou C, Manolas C, Papadopoulos N, Bougioukas G, Simopoulos C. 2011; Attenuation of propofol tolerance conferred by remifentanil co-administration does not reduce propofol toxicity in rabbits under prolonged mechanical ventilation. J Surg Res. 168:253–261. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.020. PMID: 20036388.

Article11. Bidani A, Churchill PC. 1989; Acute renal failure. Dis Mon. 35:57–132. DOI: 10.1016/0011-5029(89)90017-5. PMID: 2647437.

Article12. Yapanoglu T, Adanur S, Ziypak T, Arslan A, Kunak CS, Alp HH, Suleyman B. 2015; The comparison of resveratrol and N-acetylcysteine on the oxidative kidney damage caused by high dose paracetamol. Lat Am J Pharm. 34:973–979.13. Hohenegger M. 2012; Drug induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 12:335–339. DOI: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.04.002. PMID: 22560920. PMCID: PMC3387368.

Article14. Cray SH, Robinson BH, Cox PN. 1998; Lactic acidemia and bradyarrhythmia in a child sedated with propofol. Crit Care Med. 26:2087–2092. DOI: 10.1097/00003246-199812000-00046. PMID: 9875925.

Article15. Keltz E, Khan FY, Mann G. 2014; Rhabdomyolysis. The role of diagnostic and prognostic factors. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 3:303–312. DOI: 10.32098/mltj.04.2013.11. PMID: 24596694. PMCID: PMC3940504.

Article16. Orrenius S, Burkitt MJ, Kass GE, Dypbukt JM, Nicotera P. 1992; Calcium ions and oxidative cell injury. Ann Neurol. 32 Suppl:S33–S42. DOI: 10.1002/ana.410320708. PMID: 1510379.

Article17. Gu H, Yang M, Zhao X, Zhao B, Sun X, Gao X. 2014; Pretreatment with hydrogen-rich saline reduces the damage caused by glycerol-induced rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury in rats. J Surg Res. 188:243–249. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.12.007. PMID: 24495844.

Article18. Reiter RJ. 1995; Oxidative processes and antioxidative defense mechanisms in the aging brain. FASEB J. 9:526–533. DOI: 10.1096/fasebj.9.7.7737461. PMID: 7737461.19. Park SK, Kang JY, Kim JM, Park SH, Kwon BS, Kim GH, Heo HJ. 2018; Protective effect of fucoidan extract from Ecklonia cava on hydrogen peroxide-induced neurotoxicity. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 28:40–49. DOI: 10.4014/jmb.1710.10043. PMID: 29121706.

Article20. Mathews CK, Van Holde KE, Ahern KG. 2000. Biochemistry. 3rd ed. Addison Wesley Longman;San Francisco (CA):21. Dutka TL, Lamb GD. 2004; Effect of low cytoplasmic [ATP] on excitation-contraction coupling in fast-twitch muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol. 560(Pt 2):451–468. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069112. PMID: 15308682. PMCID: PMC1665263.

Article22. Kumbasar S, Cetin N, Yapca OE, Sener E, Isaoglu U, Yilmaz M, Salman S, Aksoy AN, Gul MA, Suleyman H. 2014; Exogenous ATP administration prevents ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and tissue injury by modulation of hypoxanthine metabolic pathway in rat ovary. Cienc Rural. 44:1257–1263. DOI: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20131006.

Article23. Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. 1979; Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 95:351–358. DOI: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. PMID: 36810.

Article24. Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. 1968; Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal Biochem. 25:192–205. DOI: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. PMID: 4973948.

Article25. Skitek M, Kranjec I, Jerin A. 2014; Glycogen phosphorylase isoenzyme BB, creatine kinase isoenzyme MB and troponin I for monitoring patients with percutaneous coronary intervention - a pilot study. Med Glas (Zenica). 11:13–18. PMID: 24496335.26. Totsuka M, Nakaji S, Suzuki K, Sugawara K, Sato K. 2002; Break point of serum creatine kinase release after endurance exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 93:1280–1286. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2001. PMID: 12235026.27. Baird MF, Graham SM, Baker JS, Bickerstaff GF. 2012; Creatine-kinase- and exercise-related muscle damage implications for muscle performance and recovery. J Nutr Metab. 2012:960363. DOI: 10.1155/2012/960363. PMID: 22288008. PMCID: PMC3263635.

Article28. Grobben RB, Nathoe HM, Januzzi JL Jr, van Kimmenade RR. 2014; Cardiac markers following cardiac surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Lab Med. 34:99–111. viiDOI: 10.1016/j.cll.2013.11.013. PMID: 24507790.

Article29. Siegel AJ, Silverman LM, Evans WJ. 1983; Elevated skeletal muscle creatine kinase MB isoenzyme levels in marathon runners. JAMA. 250:2835–2837. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1983.03340200069032. PMID: 6644963.

Article30. Ricchiuti V, Voss EM, Ney A, Odland M, Apple FS. 2004; Skeletal muscle expression of creatine kinase-B in end-stage renal disease. Clin Proteom. 1:33–39. DOI: 10.1385/CP:1:1:033.

Article31. Kiely PD, Bruckner FE, Nisbet JA, Daghir A. 2000; Serum skeletal troponin I in inflammatory muscle disease: relation to creatine kinase, CKMB and cardiac troponin I. Ann Rheum Dis. 59:750–751. DOI: 10.1136/ard.59.9.750. PMID: 11023449. PMCID: PMC1753274.

Article32. Stelow EB, Johari VP, Smith SA, Crosson JT, Apple FS. 2000; Propofol-associated rhabdomyolysis with cardiac involvement in adults: chemical and anatomic findings. Clin Chem. 46:577–581. DOI: 10.1093/clinchem/46.4.577. PMID: 10759487.

Article33. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. 2000; Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 36:959–969. DOI: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. PMID: 10987628.34. Hussein A, Ahmed AA, Shouman SA, Sharawy S. 2012; Ameliorating effect of DL-α-lipoic acid against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and cardiotoxicity in experimental animals. Drug Discov Ther. 6:147–156. DOI: 10.5582/ddt.2012.v6.3.147. PMID: 22890205.

Article35. Mallard JM, Rieser TM, Peterson NW. 2018; Propofol infusion-like syndrome in a dog. Can Vet J. 59:1216–1222. PMID: 30410181. PMCID: PMC6190180.36. Jo KM, Heo NY, Park SH, Moon YS, Kim TO, Park J, Choi JH, Park YE, Lee J. 2019; Serum aminotransferase level in rhabdomyolysis according to concurrent liver disease. Korean J Gastroenterol. 74:205–211. DOI: 10.4166/kjg.2019.74.4.205. PMID: 31650796.

Article37. Wroblewski F. 1958; The clinical significance of alterations in transaminase activities of serum and other body fluids. Adv Clin Chem. 1:313–351. DOI: 10.1016/S0065-2423(08)60362-5. PMID: 13571034.38. Pratt DS. Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors. 2016. Liver chemistry and function tests. Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease. 10th ed. Saunders/Elsevier;Philadelphia (PA): p. 1245–1246.

Article39. El-Ganainy SO, El-Mallah A, Abdallah D, Khattab MM, Mohy El-Din MM, El-Khatib AS. 2016; Elucidation of the mechanism of atorvastatin-induced myopathy in a rat model. Toxicology. 359-360:29–38. DOI: 10.1016/j.tox.2016.06.015. PMID: 27345130.

Article40. Farswan M, Rathod SP, Upaganlawar AB, Semwal A. 2005; Protective effect of coenzyme Q10 in simvastatin and gemfibrozil induced rhabdomyolysis in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 43:845–848. PMID: 16235714.41. Dickey DT, Muldoon LL, Doolittle ND, Peterson DR, Kraemer DF, Neuwelt EA. 2008; Effect of N-acetylcysteine route of administration on chemoprotection against cisplatin-induced toxicity in rat models. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 62:235–241. DOI: 10.1007/s00280-007-0597-2. PMID: 17909806. PMCID: PMC2776068.

Article42. Chew DJ, Dibartola SP. Ettinger SJ, editor. 1989. Diagnosis and pathophysiology of renal disease. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine: Diseases of the dog and cat. 3rd ed. W.B. Saunders;Philadelphia (PA): p. 1893–1961.43. Goulart M, Batoréu MC, Rodrigues AS, Laires A, Rueff J. 2005; Lipoperoxidation products and thiol antioxidants in chromium exposed workers. Mutagenesis. 20:311–315. DOI: 10.1093/mutage/gei043. PMID: 15985443.

Article44. Urso ML, Clarkson PM. 2003; Oxidative stress, exercise, and antioxidant supplementation. Toxicology. 189:41–54. DOI: 10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00151-3. PMID: 12821281.

Article45. Chaudry IH. 1982; Does ATP cross the cell plasma membrane. Yale J Biol Med. 55:1–10. PMID: 7051582. PMCID: PMC2595991.46. Fedelesová M, Ziegelhöffer A, Krause EG, Wollenberger A. 1969; Effect of exogenous adenosine triphosphate on the metabolic state of the excised hypothermic dog heart. Circ Res. 24:617–627. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.24.5.617. PMID: 5770252.47. Hou Q, Wang Y, Fan B, Sun K, Liang J, Feng H, Jia L. 2020; Extracellular ATP affects cell viability, respiratory O2 uptake, and intracellular ATP production of tobacco cell suspension culture in response to hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress. Biologia. 75:1437–1443. DOI: 10.2478/s11756-020-00442-w.

Article48. Nance JR, Mammen AL. 2015; Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve. 51:793–810. DOI: 10.1002/mus.24606. PMID: 25678154. PMCID: PMC4437836.

Article49. Lindberg C, Sixt C, Oldfors A. 2012; Episodes of exercise-induced dark urine and myalgia in LGMD 2I. Acta Neurol Scand. 125:285–287. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01608.x. PMID: 22029705.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Efficacy of adenosine triphosphate in infants and children with supraventricular tachycardia

- Early changes in tissue ATP. glucose and lactate following vascular occlusion in island skin flaps of the rats

- Assessment of Coronary Flow Reserve with Adenosine Triphosphate Compared to the Response to Adenosine

- Effect of Caffeine on UTP-induced Ca2+ Mobilization and Mucin Secretion in Human Middle Ear Epithelial Cells

- Effects of Adenosine 5'-Tetraphosphate on the Cardiac Activity*