Korean Circ J.

2020 Nov;50(11):1026-1036. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0172.

Impact of Hospital Volume of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) on In-Hospital Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Based on the 2014 Cohort of the Korean Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (K-PCI) Registry

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Gyeongju, Korea

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Cardiovascular Center, Dongguk University Illsan Hospital, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea

- 3Division of Cardiology, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

- 4Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Vincent's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Suwon, Korea

- 5Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Bucheon, Korea

- 7Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Cheju Halla General Hospital, Jeju, Korea

- 8Department of Cardiology, Korea University Ansan Hospital, Ansan, Korea

- 9Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kwangju Christian Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- 10Department of Internal Medicine, Pohang St. Mary's Hospital, Pohang, Korea

- 11Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Pohang Semyeong Christianity Hospital, Pohang, Korea

- 12Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2508288

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0172

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

The relationship between the hospital percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) volumes and the in-hospital clinical outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains the subject of debate. This study aimed to determine whether the in-hospital clinical outcomes of patients with AMI in Korea are significantly associated with hospital PCI volumes.

Methods

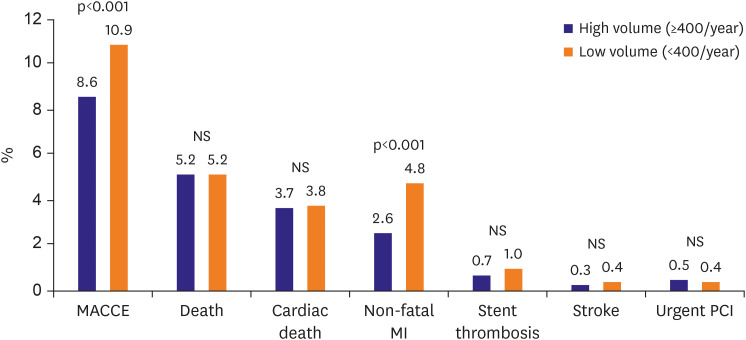

We selected and analyzed 17,121 cases of AMI, that is, 8,839 cases of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and 8,282 cases of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, enrolled in the 2014 Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to hospital annual PCI volume, that is, to a high-volume group (≥400/year) or a low-volume group (<400/year). Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) were defined as composites of death, cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), stent thrombosis, stroke, and need for urgent PCI during index admission after PCI.

Results

Rates of MACCE and non-fatal MI were higher in the low-volume group than in the high-volume group (MACCE: 10.9% vs. 8.6%, p=0.001; non-fatal MI: 4.8% vs. 2.6%, p=0.001, respectively). Multivariate regression analysis showed PCI volume did not independently predict MACCE.

Conclusions

Hospital PCI volume was not found to be an independent predictor of in-hospital clinical outcomes in patients with AMI included in the 2014 K-PCI registry.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Is Hospital Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Volume-In-hospital Outcome Relation an Issue in Acute Myocardial Infarction?

Seung-Woon Rha

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(11):1037-1039. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0383.Does Hospital Volume of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Matter on Mid-Term Mortality?: from the Data of National Health Insurance Service in Korea

Jang-Whan Bae

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(6):530-532. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0122.

Reference

-

1. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 67:1235–1250. PMID: 26498666.2. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011; 124:2574–2609. PMID: 22064598.3. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:87–165. PMID: 30165437.4. Canto JG, Every NR, Magid DJ, et al. The volume of primary angioplasty procedures and survival after acute myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1573–1580. PMID: 10824077.5. Vakili BA, Kaplan R, Brown DL. Volume-outcome relation for physicians and hospitals performing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction in New York state. Circulation. 2001; 104:2171–2176. PMID: 11684626.

Article6. Spaulding C, Morice MC, Lancelin B, et al. Is the volume-outcome relation still an issue in the era of PCI with systematic stenting? Results of the greater Paris area PCI registry. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:1054–1060. PMID: 16569652.

Article7. Shiraishi J, Kohno Y, Sawada T, et al. Effects of hospital volume of primary percutaneous coronary interventions on angiographic results and in-hospital outcomes for acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2008; 72:1041–1046. PMID: 18577809.

Article8. Tsuchihashi M, Tsutsui H, Tada H, et al. Volume-outcome relation for hospitals performing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: results from the nationwide Japanese registry. Circ J. 2004; 68:887–891. PMID: 15459459.9. Badheka AO, Patel NJ, Grover P, et al. Impact of annual operator and institutional volume on percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes: a 5-year United States experience (2005-2009). Circulation. 2014; 130:1392–1406. PMID: 25189214.10. Lee JH, Eom SY, Kim U, et al. Effect of operator volume on in-hospital outcomes following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: based on the 2014 cohort of Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:133–144. PMID: 31845555.

Article11. Hirshfeld JW Jr, Ellis SG, Faxon DP. Recommendations for the assessment and maintenance of proficiency in coronary interventional procedures: statement of the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 31:722–743. PMID: 9502660.12. Milstein A, Galvin RS, Delbanco SF, Salber P, Buck CR Jr. Improving the safety of health care: the leapfrog initiative. Eff Clin Pract. 2000; 3:313–316. PMID: 11151534.13. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2551–2567. PMID: 22922414.14. Dawkins KD, Gershlick T, de Belder M, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention: recommendations for good practice and training. Heart. 2005; 91(Suppl 6):vi1–vi27. PMID: 16365340.

Article15. Post PN, Kuijpers M, Ebels T, Zijlstra F. The relation between volume and outcome of coronary interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010; 31:1985–1992. PMID: 20511324.

Article16. Banning AP, Baumbach A, Blackman D, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in the UK: recommendations for good practice 2015. Heart. 2015; 101(Suppl 3):1–13. PMID: 26041756.

Article17. Dehmer GJ, Weaver D, Roe MT, et al. A contemporary view of diagnostic cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: a report from the CathPCI Registry of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, 2010 through June 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:2017–2031. PMID: 23083784.18. Jang JS, Han KR, Moon KW, et al. The current status of percutaneous coronary intervention in Korea: based on year 2014 cohort of Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:328–340. PMID: 28567083.

Article19. Hong SJ, Mintz GS, Ahn CM, et al. Effect of intravascular ultrasound-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: 5-year follow-up of the IVUS-XPL randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13:62–71. PMID: 31918944.20. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:213–224. PMID: 19144937.

Article21. Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Yamaji K, et al. Impact of institutional and operator volume on short-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the Japanese nationwide registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017; 10:918–927. PMID: 28473114.22. Langabeer JR 2nd, Kim J, Helton J. Exploring the relationship between volume and outcomes in hospital cardiovascular care. Qual Manag Health Care. 2017; 26:160–164. PMID: 28665907.

Article23. Kim YH, Her AY. Relationship between hospital volume and risk-adjusted mortality rate following percutaneous coronary intervention in Korea, 2003 to 2004. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2013; 13:237–242. PMID: 23395704.

Article24. Harold JG, Bass TA, Bashore TM, et al. ACCF/AHA/SCAI 2013 update of the clinical competence statement on coronary artery interventional procedures: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training (Writing Committee to Revise the 2007 Clinical Competence Statement on Cardiac Interventional Procedures). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:357–396. PMID: 23665367.25. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. EuroIntervention. 2015; 10:1024–1094. PMID: 25187201.

Article26. Kumbhani DJ, Cannon CP, Fonarow GC, et al. Association of hospital primary angioplasty volume in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with quality and outcomes. JAMA. 2009; 302:2207–2213. PMID: 19934421.

Article27. Desai NR, Bradley SM, Parzynski CS, et al. Appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization and trends in utilization, patient selection, and appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2015; 314:2045–2053. PMID: 26551163.

Article28. Maroney J, Khan S, Powell W, Klein LW. Current operator volumes of invasive coronary procedures in Medicare patients: implications for future manpower needs in the catheterization laboratory. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 81:34–39. PMID: 22431421.

Article29. Fanaroff AC, Zakroysky P, Dai D, et al. Outcomes of PCI in relation to procedural characteristics and operator volumes in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:2913–2924. PMID: 28619191.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Prognostic Impact of Hypertriglyceridemia and Abdominal Obesity in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Current Status of Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

- Consecutive Multivessel Myocardial Infarction during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Unprotected Left Main Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in a 108-Year-Old Patient

- Usefulness of Myocardial Perfusion SPECT after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)