J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Sep;35(38):e334. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e334.

Factors Affecting Collaborations between a Tertiary-level Emergency Department and Community-based Mental Healthcare Centers for Managing Suicide Attempts

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Incheon St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Incheon, Korea

- 2Department of Counseling Psychology, Graduate School of Theology, Seoul Theological University, Bucheon, Korea

- 3Department of Emergency Medical Service, College of Health and Nursing, Kongju National University, Gongju, Korea

- 4Department of Nuclear Medicine, Ewha Womans University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2507085

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e334

Abstract

- Background

Community-based active contact and follow-up are known to be effective in reducing the risk of repeat suicide attempts among patients admitted to emergency departments after attempting suicide. However, the characteristics that define successful collaborations between emergency departments and community-based mental healthcare centers in this context are not well known.

Methods

This study investigated patients visiting the emergency department after suicide attempts from May 2017 to April 2019. Patients were classified in either the successful collaboration group or the failed collaboration group depending on whether or not they were linked to a community-based follow-up intervention. Clinical features and socioeconomic status were considered as independent variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors influencing the collaboration.

Results

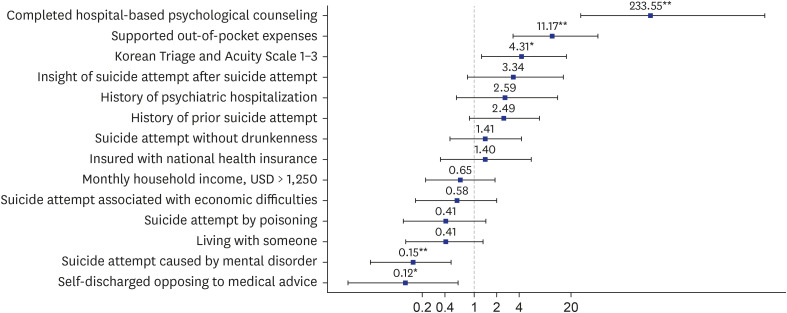

Of 674 patients, 153 (22.7%) were managed successfully via the targeted collaboration. Completion of hospital-based psychological counseling (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 233.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 14.99–3,637.67), supported out-of-pocket expenses (aOR, 11.17; 95% CI, 3.03–41.03), Korean Triage and Acuity Scale 1–3 (aOR, 4.31; 95% CI, 1.18–15.73), suicide attempt associated with mental disorder (aOR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.04–0.52), and self-discharge against medical advice (aOR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.02–0.70) were independent factors influencing the collaboration.

Conclusion

Completion of hospital-based psychological counseling was the most highly influential factor determining the outcome of the collaboration between the emergency department and community-based mental healthcare center in the management of individuals who had attempted suicide. Completion of hospital-based psychological counseling is expected to help reduce the risk of repeat suicide attempts.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Rudd MD, Goulding JM, Carlisle CJ. Stigma and suicide warning signs. Arch Suicide Res. 2013; 17(3):313–318. PMID: 23889579.

Article2. World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization;2014.3. World Health Organization. Suicide prevention (SUPRE). Updated 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/.4. Ting SA, Sullivan AF, Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Camargo CA Jr. Trends in US emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1993-2008. Crisis. 2008; 29(2):73–80. PMID: 18664232.

Article5. Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, Sivilotti ML, Hutson JR, Mamdani MM, et al. Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015; 72(6):570–575. PMID: 25830811.

Article6. Artieda-Urrutia P, Parra Uribe I, Garcia-Pares G, Palao D, de Leon J, Blasco-Fontecilla H. Management of suicidal behaviour: is the world upside down? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014; 48(5):399–401. PMID: 24589981.

Article7. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005; 294(16):2064–2074. PMID: 16249421.8. Morthorst B, Krogh J, Erlangsen A, Alberdi F, Nordentoft M. Effect of assertive outreach after suicide attempt in the AID (assertive intervention for deliberate self harm) trial: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012; 345:e4972. PMID: 22915730.

Article9. Wei S, Liu L, Bi B, Li H, Hou J, Tan S, et al. An intervention and follow-up study following a suicide attempt in the emergency departments of four general hospitals in Shenyang, China. Crisis. 2013; 34(2):107–115. PMID: 23261916.

Article10. Battaglia J, Wolff TK, Wagner-Johnson DS, Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, Basco MR. Structured diagnostic assessment and depot fluphenazine treatment of multiple suicide attempters in the emergency department. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999; 14(6):361–372. PMID: 10565804.

Article11. Inagaki M, Kawashima Y, Kawanishi C, Yonemoto N, Sugimoto T, Furuno T, et al. Interventions to prevent repeat suicidal behavior in patients admitted to an emergency department for a suicide attempt: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2015; 175:66–78. PMID: 25594513.

Article12. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Bridge JA. Emergency treatment of deliberate self-harm. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012; 69(1):80–88. PMID: 21893643.

Article13. Cooper J, Steeg S, Bennewith O, Lowe M, Gunnell D, House A, et al. Are hospital services for self-harm getting better? An observational study examining management, service provision and temporal trends in England. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(11):e003444.

Article14. Shand FL, Batterham PJ, Chan JK, Pirkis J, Spittal MJ, Woodward A, et al. Experience of health care services after a suicide attempt: results from an online survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018; 48(6):779–787. PMID: 28960505.

Article15. Mork E, Mehlum L, Fadum EA, Rossow I. Collaboration between general hospitals and community health services in the care of suicide attempters in Norway: a longitudinal study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2010; 9:26. PMID: 20540725.

Article16. Kim JH, Kim JW, Kim SY, Hong DY, Park SO, Baek KJ, et al. Validation of the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale compare to triage by emergency severity index for emergency adult patient: preliminary study in a tertiary hospital emergency medical center. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2016; 27(5):436–441.17. Korean National Statistical Office. 2018 Death and Cause of Death in Korea. Daejeon: Korea: Korean National Statistical Office;2019.18. Jeon HJ, Lee JY, Lee YM, Hong JP, Won SH, Cho SJ, et al. Lifetime prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation, plan, and single and multiple attempts in a Korean nationwide study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010; 198(9):643–646. PMID: 20823725.

Article19. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). Korea Suicide Prevention Center. White Book. Seoul: Suicide Prevention Center;2017.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Efficacy of a Program Associated with a Local Community of Suicide Attempters who Visited a Regional Emergency Medical Center

- Suicidal Behaviors Among Public Community Healthcare Center Registrants: A Comparison of Mental and General Healthcare Center Registrants in Korea

- Analysis of social factors influencing authenticity of suicide for patient who attempt to suicide in emergency department: Retrospective study based Post-suicidal Care Program data

- Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Low-rescue Suicide Attempts in Patients Visiting the Emergency Department after Attempting Suicide

- Characteristics of Suicide Attempters Admitted to the Emergency Room and Factors Related to Repetitive Suicide Attempts