Ann Rehabil Med.

2020 Jun;44(3):246-255. 10.5535/arm.19100.

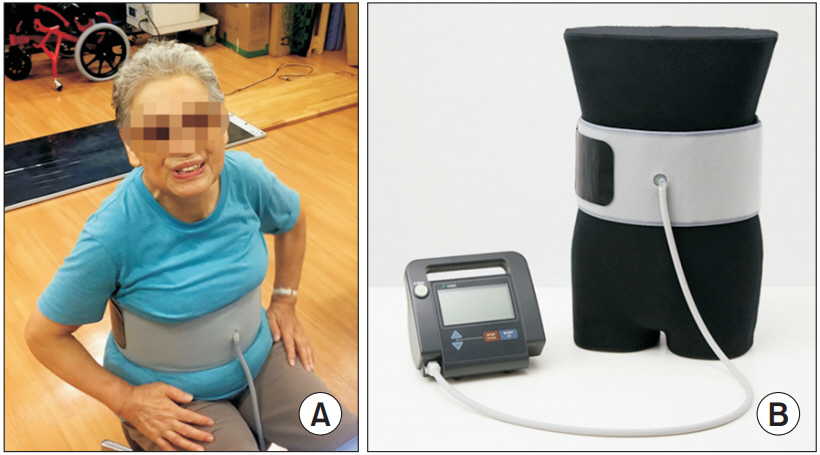

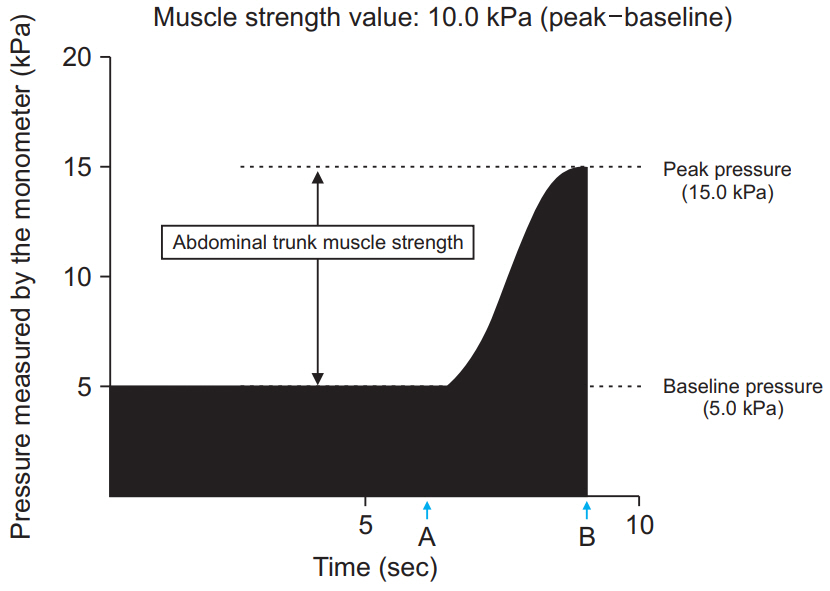

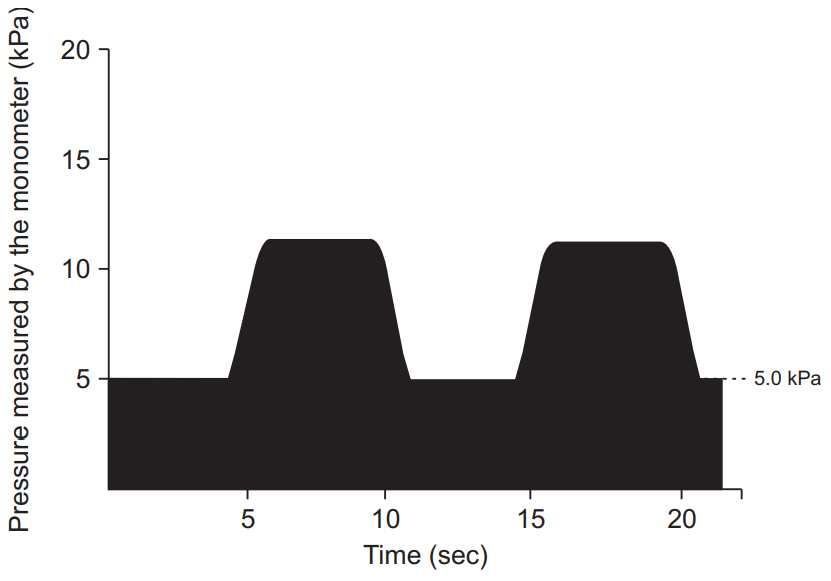

Efficacy and Safety of Abdominal Trunk Muscle Strengthening Using an Innovative Device in Elderly Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pilot Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan

- KMID: 2504445

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5535/arm.19100

Abstract

Objective

To examine the efficacy and safety of an innovative, device-driven abdominal trunk muscle strengthening program, with the ability to measure muscle strength, to treat chronic low back pain (LBP) in elderly participants.

Methods

Seven women with non-specific chronic LBP, lasting at least 3 months, were enrolled and treated with the prescribed exercise regimen. Patients participated in a 12-week device-driven exercise program which included abdominal trunk muscle strengthening and 4 types of stretches for the trunk and lower extremities. Primary outcomes were adverse events associated with the exercise program, improvement in abdominal trunk muscle strength, as measured by the device, and improvement in the numerical rating scale (NRS) scores of LBP with the exercise. Secondary outcomes were improvement in the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) score and the results of the locomotive syndrome risk test, including the stand-up and two-step tests.

Results

There were no reports of increased back pain or new-onset abdominal pain or discomfort during or after the device-driven exercise program. The mean abdominal trunk muscle strength, NRS, RDQ scores, and the stand-up and two-step test scores were significantly improved at the end of the trial compared to baseline.

Conclusion

No participants experienced adverse events during the 12-week strengthening program, which involved the use of our device and stretching, indicating the program was safe. Further, the program significantly improved various measures of LBP and physical function in elderly participants.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J. 2008; 8:8–20.

Article2. Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA, Badley E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly: a systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999; 24:1813–9.3. Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of LBP: reaching a specific diagnosis is often impossible. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162:1444–8.4. Poitras S, Brosseau L. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, interferential current, electrical muscle stimulation, ultrasound, and thermotherapy. Spine J. 2008; 8:226–33.

Article5. Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Kawchuk G, Dagenais S. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with spinal manipulation and mobilization. Spine J. 2008; 8:213–25.

Article6. Standaert CJ, Weinstein SM, Rumpeltes J. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with lumbar stabilization exercises. Spine J. 2008; 8:114–20.

Article7. Mayer J, Mooney V, Dagenais S. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with lumbar extensor strengthening exercises. Spine J. 2008; 8:96–113.

Article8. Slade SC, Keating JL. Trunk-strengthening exercises for chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006; 29:163–73.

Article9. Oesch P, Kool J, Hagen KB, Bachmann S. Effectiveness of exercise on work disability in patients with non-acute non-specific low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2010; 42:193–205.

Article10. Dagenais S, Tricco AC, Haldeman S. Synthesis of recommendations for the assessment and management of low back pain from recent clinical practice guidelines. Spine J. 2010; 10:514–29.

Article11. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142:776–85.

Article12. Phillips EM, Schneider JC, Mercer GR. Motivating elders to initiate and maintain exercise. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 85(7 Suppl 3):S52–7.13. Rudy TE, Weiner DK, Lieber SJ, Slaboda J, Boston JR. The impact of chronic low back pain on older adults: a comparative study of patients and controls. Pain. 2007; 131:293–301.

Article14. Coyle PC, Velasco T, Sions JM, Hicks GE. Lumbar mobility and performance-based function: an investigation in older adults with and without chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2017; 18:161–8.

Article15. Nakamura K. A “super-aged” society and the “locomotive syndrome”. J Orthop Sci. 2008; 13:1–2.

Article16. Nakamura K, Ogata T. Locomotive syndrome: definition and management. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2016; 14:56–67.

Article17. Kato S, Murakami H, Inaki A, Mochizuki T, Demura S, Nakase J, et al. Innovative exercise device for the abdominal trunk muscles: an early validation study. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0172934.

Article18. Kato S, Inaki A, Murakami H, Kurokawa Y, Mochizuki T, et al. Reliability of the muscle strength measurement and effects of the strengthening by an innovative exercise device for the abdominal trunk muscles. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2019; Oct. 15. [Epub]. http://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-181419.

Article19. Kavcic N, Grenier S, McGill SM. Determining the stabilizing role of individual torso muscles during rehabilitation exercises. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004; 29:1254–65.

Article20. Ogata T, Muranaga S, Ishibashi H, Ohe T, Izumida R, Yoshimura N, et al. Development of a screening program to assess motor function in the adult population: a cross-sectional observational study. J Orthop Sci. 2015; 20:888–95.

Article21. Richardson CA, Jull GA. Muscle control-pain control: what exercises would you prescribe? Man Ther. 1995; 1:2–10.

Article22. Akuthota V, Ferreiro A, Moore T, Fredericson M. Core stability exercise principles. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008; 7:39–44.

Article23. Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Latimer J, Herbert RD, Hodges PW, Jennings MD, et al. Comparison of general exercise, motor control exercise and spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. Pain. 2007; 131:31–7.

Article24. Brown SH, Vera-Garcia FJ, McGill SM. Effects of abdominal muscle coactivation on the externally preloaded trunk: variations in motor control and its effect on spine stability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006; 31:E387–93.

Article25. Grenier SG, McGill SM. Quantification of lumbar stability by using 2 different abdominal activation strategies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007; 88:54–62.

Article26. Vera-Garcia FJ, Elvira JL, Brown SH, McGill SM. Effects of abdominal stabilization maneuvers on the control of spine motion and stability against sudden trunk perturbations. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2007; 17:556–67.

Article27. Akuthota V, Nadler SF. Core strengthening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 85(3 Suppl 1):S86–92.28. Okubo Y, Kaneoka K, Imai A, Shiina I, Tatsumura M, Izumi S, et al. Electromyographic analysis of transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus using wire electrodes during lumbar stabilization exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010; 40:743–50.

Article29. Helewa A, Goldsmith C, Smythe H, Gibson E. An evaluation of four different measures of abdominal muscle strength: patient, order and instrument variation. J Rheumatol. 1990; 17:965–9.30. Lee JH, Ooi Y, Nakamura K. Measurement of muscle strength of the trunk and the lower extremities in subjects with history of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995; 20:1994–6.

Article31. Nourbakhsh MR, Arab AM. Relationship between mechanical factors and incidence of low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002; 32:447–60.

Article32. Granacher U, Gollhofer A, Hortobagyi T, Kressig RW, Muehlbauer T. The importance of trunk muscle strength for balance, functional performance, and fall prevention in seniors: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2013; 43:627–41.

Article33. Granacher U, Lacroix A, Muehlbauer T, Roettger K, Gollhofer A. Effects of core instability strength training on trunk muscle strength, spinal mobility, dynamic balance and functional mobility in older adults. Gerontology. 2013; 59:105–13.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effects of Lumbar Strengthening Exercise in Lower-Limb Amputees With Chronic Low Back Pain

- Concentric and Eccentric Isokinetic Trunk Muscle Evaluation in Chronic Low Back Pain

- The Effect of Chronic Low Back Pain on Bone Mineral Density and Trunk Muscle Strength in Women

- Associations Between Trunk Muscle/Fat Composition, Narrowing Lumbar Disc Space, and Low Back Pain in Middle-Aged Farmers: A Cross-Sectional Study

- Effects of a Strengthening Program for Lower Back in Older Women with Chronic Low Back Pain