J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Apr;35(16):e102. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e102.

Factors Associated with Triage Modifications Using Vital Signs in Pediatric Triage: a NationwideCross-Sectional Study in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Emergency Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2500199

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e102

Abstract

- Background

Previous studies on inter-rater reliability of pediatric triage systems have compared triage levels classified by two or more triage providers using the same information about individual patients. This overlooks the fact that the evaluator can decide whether or not to use the information provided. The authors therefore aimed to analyze the differences in the use of vital signs for triage modification in pediatric triage.

Methods

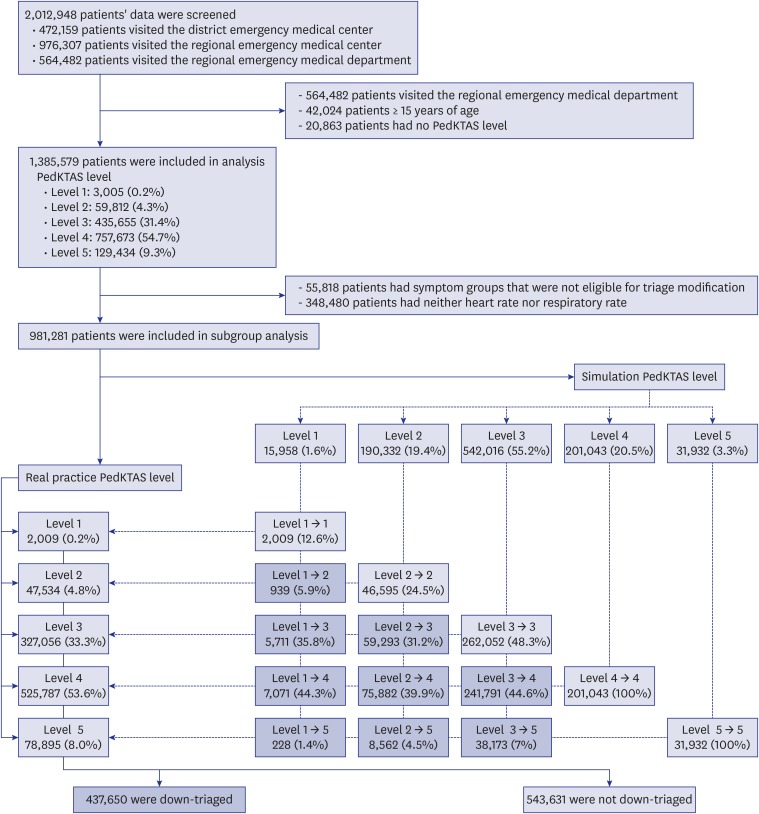

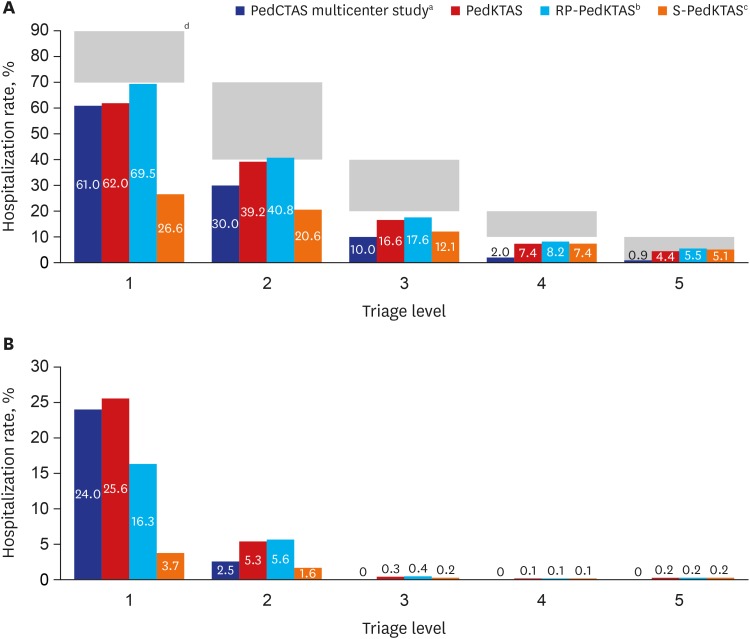

This was an observational cross-sectional study of national registry data collected in real time from all emergency medical services beyond the local emergency medical centers (EMCs) throughout Korea. Data from patients under the age of 15 who visited EMC nationwide from January 2016 to December 2016 were analyzed. Depending on whether triage modifications were made using respiratory rate or heart rate beyond the normal range by age during the pediatric triage process, they were divided into down-triage and non-down-triage groups. The proportions in the down-triage group were analyzed according to the triage provider's profession, mental status, arrival mode, presence of trauma, and the EMC class.

Results

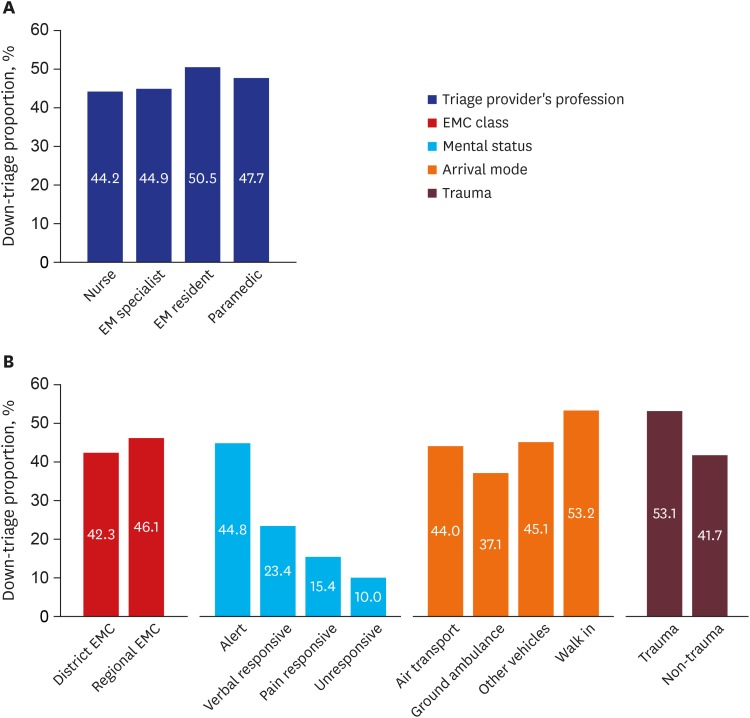

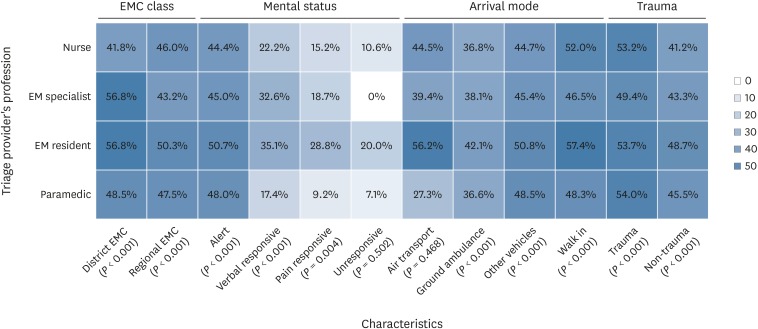

During the study period, 1,385,579 patients' data were analyzed. Of these, 981,281 patients were eligible for triage modification. The differences in down-triage proportions according to the profession of the triage provider (resident, 50.5%; paramedics, 47.7%; specialist, 44.9%; nurses, 44.2%) was statistically significant (P < 0.001). The triage provider's professional down-triage proportion according to the medical condition of the patients showed statistically significant differences except for the unresponsive mental state (P = 0.502) and the case of air transport (P = 0.468).

Conclusion

Down-triage proportion due to abnormal heart rates and respiratory rates was significantly different according to the triage provider's condition. The existing concept of inter-rater reliability of the pediatric triage system needs to be reconsidered.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. de Caen AR, Maconochie IK, Aickin R, Atkins DL, Biarent D, Guerguerian AM, et al. Part 6: pediatric basic life support and pediatric advanced life support: 2015 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2015; 132(16):Suppl 1. S177–S203. PMID: 26472853.2. Maconochie IK, Bingham R, Eich C, López-Herce J, Rodríguez-Núñez A, Rajka T, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 6. paediatric life support. Resuscitation. 2015; 95:223–248. PMID: 26477414.3. Parshuram CS, Duncan HP, Joffe AR, Farrell CA, Lacroix JR, Middaugh KL, et al. Multicentre validation of the bedside paediatric early warning system score: a severity of illness score to detect evolving critical illness in hospitalised children. Crit Care. 2011; 15(4):R184. PMID: 21812993.

Article4. Duncan H, Hutchison J, Parshuram CS. The pediatric early warning system score: a severity of illness score to predict urgent medical need in hospitalized children. J Crit Care. 2006; 21(3):271–278. PMID: 16990097.

Article5. Warren DW, Jarvis A, LeBlanc L, Gravel J, et al. CTAS National Working Group. Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Revisions to the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale paediatric guidelines (PaedCTAS). CJEM. 2008; 10(3):224–243. PMID: 19019273.

Article6. Bullard MJ, Chan T, Brayman C, Warren D, Musgrave E, Unger B, et al. Revisions to the Canadian emergency department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) guidelines. CJEM. 2014; 16(6):485–489. PMID: 25358280.

Article7. Takahashi T, Inoue N, Shimizu N, Terakawa T, Goldman RD. ‘Down-triage’ for children with abnormal vital signs: evaluation of a new triage practice at a paediatric emergency department in Japan. Emerg Med J. 2016; 33(8):533–537. PMID: 27044947.

Article8. Lee B, Kim DK, Park JD, Kwak YH. Clinical considerations when applying vital signs in pediatric Korean Triage and Acuity Scale. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(10):1702–1707. PMID: 28875617.

Article9. Bullard MJ, Musgrave E, Warren D, Unger B, Skeldon T, Grierson R, et al. Revisions to the Canadian emergency department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) guidelines 2016. CJEM. 2017; 19(S2):S18–S27. PMID: 28756800.

Article10. Sprivulis PC, Da Silva JA, Jacobs IG, Frazer AR, Jelinek GA. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust. 2006; 184(5):208–212. PMID: 16515429.

Article11. Participant's manual for the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale: combined adult/paediatric education program. Updated 2013. Accessed April 26, 2019. http://ctas-phctas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/participant_manual_v2.5b_november_2013_0.pdf.12. Aeimchanbanjong K, Pandee U. Validation of different pediatric triage systems in the emergency department. World J Emerg Med. 2017; 8(3):223–227. PMID: 28680520.

Article13. Alquraini M, Awad E, Hijazi R. Reliability of Canadian emergency department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) in Saudi Arabia. Int J Emerg Med. 2015; 8(1):80. PMID: 26251308.

Article14. Mirhaghi A, Heydari A, Mazlom R, Ebrahimi M. The reliability of the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale: meta-analysis. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7(7):299–305. PMID: 26258076.

Article15. van Veen M, Moll HA. Reliability and validity of triage systems in paediatric emergency care. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009; 17(1):38. PMID: 19712467.

Article16. Dalwai M, Tayler-Smith K, Twomey M, Nasim M, Popal AQ, Haqdost WH, et al. Inter-rater and intrarater reliability of the South African Triage Scale in low-resource settings of Haiti and Afghanistan. Emerg Med J. 2018; 35(6):379–383. PMID: 29549171.

Article17. Karjala J, Eriksson S. Inter-rater reliability between nurses for a new paediatric triage system based primarily on vital parameters: the Paediatric Triage Instrument (PETI). BMJ Open. 2017; 7(2):e012748.

Article18. Magalhães-Barbosa MC, Robaina JR, Prata-Barbosa A, Lopes CS. Reliability of triage systems for paediatric emergency care: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2019; 36(4):231–238. PMID: 30630838.

Article19. Gravel J, Gouin S, Bailey B, Roy M, Bergeron S, Amre D. Reliability of a computerized version of the pediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale. Acad Emerg Med. 2007; 14(10):864–869. PMID: 17761546.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Considerations When Applying Vital Signs in Pediatric Korean Triage and Acuity Scale

- Consideration in Korean Triage and Acuity Scale for febrile pediatric patients: symptom duration

- A Development of Triage in the Emergency Department

- Influence of Emergency Department Nurses' Grit, Self-Leadership, and Communication on Their Triage Competencies: A Descriptive Survey Study

- Inter-rater agreement of Korean Triage and Acuity Scale between emergency physicians and nurses