J Korean Med Sci.

2016 Nov;31(11):1673-1683. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1673.

Molecular Strain Typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a Review of Frequently Used Methods

- Affiliations

-

- 1Advanced Molecular Research Centre, Department of Medical Research, Yangon, Myanmar.

- 2International Tuberculosis Research Center, Changwon, Korea.

- 3Institute of Convergence Bio-Health, Dong-A University, Busan, Korea.

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea. cchl@pusan.ac.kr

- KMID: 2470260

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1673

Abstract

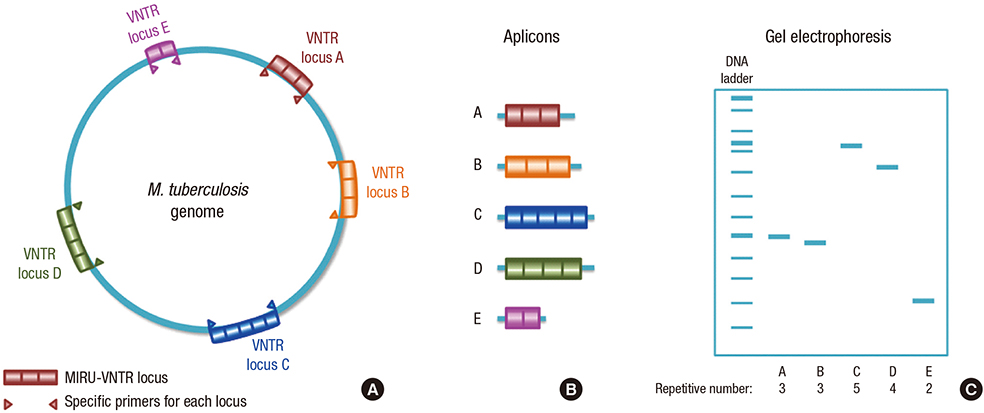

- Tuberculosis, caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains one of the most serious global health problems. Molecular typing of M. tuberculosis has been used for various epidemiologic purposes as well as for clinical management. Currently, many techniques are available to type M. tuberculosis. Choosing the most appropriate technique in accordance with the existing laboratory conditions and the specific features of the geographic region is important. Insertion sequence IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis is considered the gold standard for the molecular epidemiologic investigations of tuberculosis. However, other polymerase chain reaction-based methods such as spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping), which detects 43 spacer sequence-interspersing direct repeats (DRs) in the genomic DR region; mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units-variable number tandem repeats, (MIRU-VNTR), which determines the number and size of tandem repetitive DNA sequences; repetitive-sequence-based PCR (rep-PCR), which provides high-throughput genotypic fingerprinting of multiple Mycobacterium species; and the recently developed genome-based whole genome sequencing methods demonstrate similar discriminatory power and greater convenience. This review focuses on techniques frequently used for the molecular typing of M. tuberculosis and discusses their general aspects and applications.

MeSH Terms

-

DNA Transposable Elements/genetics

High-Throughput Nucleotide Sequencing

Humans

Molecular Typing/*methods

Mycobacterium tuberculosis/genetics/*isolation & purification/metabolism

Nucleic Acid Hybridization

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Polymorphism, Restriction Fragment Length

Tandem Repeat Sequences/genetics

Tuberculosis/microbiology

DNA Transposable Elements

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015 [Internet]. accessed on 9 September 2016. Available at http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.2. Gutacker MM, Mathema B, Soini H, Shashkina E, Kreiswirth BN, Graviss EA, Musser JM. Single-nucleotide polymorphism-based population genetic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from 4 geographic sites. J Infect Dis. 2006; 193:121–128.3. van Soolingen D, Borgdorff MW, de Haas PE, Sebek MM, Veen J, Dessens M, Kremer K, van Embden JD. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in the Netherlands: a nationwide study from 1993 through 1997. J Infect Dis. 1999; 180:726–736.4. National Tuberculosis Controllers Association (US). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Group on Tuberculosis Genotyping (US). Guide to the Application of Genotyping to Tuberculosis Prevention and Control. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2004.5. Jagielski T, Minias A, van Ingen J, Rastogi N, Brzostek A, Żaczek A, Dziadek J. Methodological and clinical aspects of the molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016; 29:239–290.6. Foxman B, Riley L. Molecular epidemiology: focus on infection. Am J Epidemiol. 2001; 153:1135–1141.7. Cattamanchi A, Hopewell PC, Gonzalez LC, Osmond DH, Masae Kawamura L, Daley CL, Jasmer RM. A 13-year molecular epidemiological analysis of tuberculosis in San Francisco. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006; 10:297–304.8. van Embden JD, Cave MD, Crawford JT, Dale JW, Eisenach KD, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick TM, et al. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993; 31:406–409.9. Park YK, Bai GH, Kim SJ. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from countries in the Western Pacific region. J Clin Microbiol. 2000; 38:191–197.10. Choi GE, Jang MH, Song EJ, Jeong SH, Kim JS, Lee WG, Uh Y, Roh KH, Lee HS, Shin JH, et al. IS6110-restriction fragment length polymorphism and spoligotyping analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates for investigating epidemiologic distribution in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1716–1721.11. Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997; 35:907–914.12. Yun KW, Song EJ, Choi GE, Hwang IK, Lee EY, Chang CL. Strain typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Korea by mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units-variable number of tandem repeats. Korean J Lab Med. 2009; 29:314–319.13. Supply P, Magdalena J, Himpens S, Locht C. Identification of novel intergenic repetitive units in a mycobacterial two-component system operon. Mol Microbiol. 1997; 26:991–1003.14. Cangelosi GA, Freeman RJ, Lewis KN, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Shah KS, Milan SJ, Goldberg SV. Evaluation of a high-throughput repetitive-sequence-based PCR system for DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium complex strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2004; 42:2685–2693.15. Gardy JL, Johnston JC, Ho Sui SJ, Cook VJ, Shah L, Brodkin E, Rempel S, Moore R, Zhao Y, Holt R, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and social-network analysis of a tuberculosis outbreak. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:730–739.16. Schürch AC, van Soolingen D. DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: from phage typing to whole-genome sequencing. Infect Genet Evol. 2012; 12:602–609.17. Walker TM, Ip CL, Harrell RH, Evans JT, Kapatai G, Dedicoat MJ, Eyre DW, Wilson DJ, Hawkey PM, Crook DW, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013; 13:137–146.18. Jang MH, Choi GE, Chang CL, Kim YD. Characteristics of molecular strain typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from Korea. Korean J Clin Microbiol. 2011; 14:41–47.19. Thierry D, Brisson-Noël A, Vincent-Lévy-Frébault V, Nguyen S, Guesdon JL, Gicquel B. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence, IS6110, and its application in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990; 28:2668–2673.20. Brosch R, Gordon SV, Marmiesse M, Brodin P, Buchrieser C, Eiglmeier K, Garnier T, Gutierrez C, Hewinson G, Kremer K, et al. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002; 99:3684–3689.21. Asgharzadeh M, Shahbabian K, Majidi J, Aghazadeh AM, Amini C, Jahantabi AR, Rafi A. IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from East Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006; 101:517–521.22. Wall S, Ghanekar K, McFadden J, Dale JW. Context-sensitive transposition of IS6110 in mycobacteria. Microbiology. 1999; 145:3169–3176.23. Cave MD, Eisenach KD, McDermott PF, Bates JH, Crawford JT. IS6110: conservation of sequence in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and its utilization in DNA fingerprinting. Mol Cell Probes. 1991; 5:73–80.24. van Soolingen D, Hermans PW, de Haas PE, Soll DR, van Embden JD. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991; 29:2578–2586.25. Van Embden JD, Van Soolingen D, Heersma HF, De Neeling AJ, Jones ME, Steiert M, Grek V, Mooi FR, Verhoef J. Establishment of a European network for the surveillance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MRSA and penicillin-resistant pneumococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996; 38:905–907.26. Heersma HF, Kremer K, van Embden JD. Computer analysis of IS6110 RFLP patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Methods Mol Biol. 1998; 101:395–422.27. Skuce RA, McCorry TP, McCarroll JF, Roring SM, Scott AN, Brittain D, Hughes SL, Hewinson RG, Neill SD. Discrimination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria using novel VNTR-PCR targets. Microbiology. 2002; 148:519–528.28. de Boer AS, Borgdorff MW, de Haas PE, Nagelkerke NJ, van Embden JD, van Soolingen D. Analysis of rate of change of IS6110 RFLP patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on serial patient isolates. J Infect Dis. 1999; 180:1238–1244.29. Warren RM, van der Spuy GD, Richardson M, Beyers N, Borgdorff MW, Behr MA, van Helden PD. Calculation of the stability of the IS6110 banding pattern in patients with persistent Mycobacterium tuberculosis disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:1705–1708.30. Barlow RE, Gascoyne-Binzi DM, Gillespie SH, Dickens A, Qamer S, Hawkey PM. Comparison of variable number tandem repeat and IS6110-restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses for discrimination of high- and low-copy-number IS6110 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2001; 39:2453–2457.31. Bauer J, Andersen AB, Kremer K, Miörner H. Usefulness of spoligotyping to discriminate IS6110 low-copy-number Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains cultured in Denmark. J Clin Microbiol. 1999; 37:2602–2606.32. Yang ZH, Ijaz K, Bates JH, Eisenach KD, Cave MD. Spoligotyping and polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequence fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains having few copies of IS6110. J Clin Microbiol. 2000; 38:3572–3576.33. Das S, Paramasivan CN, Lowrie DB, Prabhakar R, Narayanan PR. IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Madras, South India. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995; 76:550–554.34. Yang ZH, Mtoni I, Chonde M, Mwasekaga M, Fuursted K, Askgård DS, Bennedsen J, de Haas PE, van Soolingen D, van Embden JD, et al. DNA fingerprinting and phenotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive and HIV-seronegative patients in Tanzania. J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33:1064–1069.35. Cronin WA, Golub JE, Magder LS, Baruch NG, Lathan MJ, Mukasa LN, Hooper N, Razeq JH, Mulcahy D, Benjamin WH, et al. Epidemiologic usefulness of spoligotyping for secondary typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110. J Clin Microbiol. 2001; 39:3709–3711.36. Cowan LS, Mosher L, Diem L, Massey JP, Crawford JT. Variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110 by using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:1592–1602.37. Jagielski T, van Ingen J, Rastogi N, Dziadek J, Mazur PK, Bielecki J. Current methods in the molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacteria. Biomed Res Int. 2014; 2014:645802.38. Dale JW, Brittain D, Cataldi AA, Cousins D, Crawford JT, Driscoll J, Heersma H, Lillebaek T, Quitugua T, Rastogi N, et al. Spacer oligonucleotide typing of bacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: recommendations for standardised nomenclature. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001; 5:216–219.39. Brudey K, Driscoll JR, Rigouts L, Prodinger WM, Gori A, Al-Hajoj SA, Allix C, Aristimuño L, Arora J, Baumanis V, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex genetic diversity: mining the fourth international spoligotyping database (SpolDB4) for classification, population genetics and epidemiology. BMC Microbiol. 2006; 6:23.40. Demay C, Liens B, Burguière T, Hill V, Couvin D, Millet J, Mokrousov I, Sola C, Zozio T, Rastogi N. SITVITWEB--a publicly available international multimarker database for studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol. 2012; 12:755–766.41. Goguet de la Salmonière YO, Li HM, Torrea G, Bunschoten A, van Embden J, Gicquel B. Evaluation of spoligotyping in a study of the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 1997; 35:2210–2214.42. Cox R, Mirkin SM. Characteristic enrichment of DNA repeats in different genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997; 94:5237–5242.43. Nakamura Y, Leppert M, O’Connell P, Wolff R, Holm T, Culver M, Martin C, Fujimoto E, Hoff M, Kumlin E, et al. Variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) markers for human gene mapping. Science. 1987; 235:1616–1622.44. Nakamura Y, Carlson M, Krapcho K, Kanamori M, White R. New approach for isolation of VNTR markers. Am J Hum Genet. 1988; 43:854–859.45. Woods SA, Cole ST. A family of dispersed repeats in Mycobacterium leprae . Mol Microbiol. 1990; 4:1745–1751.46. Hermans PW, van Soolingen D, Bik EM, de Haas PE, Dale JW, van Embden JD. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect Immun. 1991; 59:2695–2705.47. Hermans PW, van Soolingen D, van Embden JD. Characterization of a major polymorphic tandem repeat in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its potential use in the epidemiology of Mycobacterium kansasii and Mycobacterium gordonae . J Bacteriol. 1992; 174:4157–4165.48. van Soolingen D, de Haas PE, Hermans PW, Groenen PM, van Embden JD. Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 1993; 31:1987–1995.49. Bigi F, Romano MI, Alito A, Cataldi A. Cloning of a novel polymorphic GC-rich repetitive DNA from Mycobacterium bovis . Res Microbiol. 1995; 146:341–348.50. Philipp WJ, Poulet S, Eiglmeier K, Pascopella L, Balasubramanian V, Heym B, Bergh S, Bloom BR, Jacobs WR Jr, Cole ST. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with Mycobacterium leprae . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996; 93:3132–3137.51. Supply P, Mazars E, Lesjean S, Vincent V, Gicquel B, Locht C. Variable human minisatellite-like regions in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Mol Microbiol. 2000; 36:762–771.52. Han H, Wang F, Xiao Y, Ren Y, Chao Y, Guo A, Ye L. Utility of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit typing for differentiating Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Wuhan, China. J Med Microbiol. 2007; 56:1219–1223.53. Kremer K, van Soolingen D, Frothingham R, Haas WH, Hermans PW, Martín C, Palittapongarnpim P, Plikaytis BB, Riley LW, Yakrus MA, et al. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J Clin Microbiol. 1999; 37:2607–2618.54. Supply P, Lesjean S, Savine E, Kremer K, van Soolingen D, Locht C. Automated high-throughput genotyping for study of global epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J Clin Microbiol. 2001; 39:3563–3571.55. Frothingham R, Meeker-O’Connell WA. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology. 1998; 144:1189–1196.56. Mazars E, Lesjean S, Banuls AL, Gilbert M, Vincent V, Gicquel B, Tibayrenc M, Locht C, Supply P. High-resolution minisatellite-based typing as a portable approach to global analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis molecular epidemiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001; 98:1901–1906.57. Lee AS, Tang LL, Lim IH, Bellamy R, Wong SY. Discrimination of single-copy IS6110 DNA fingerprints of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates by high-resolution minisatellite-based typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:657–659.58. Kam KM, Yip CW, Tse LW, Leung KL, Wong KL, Ko WM, Wong WS. Optimization of variable number tandem repeat typing set for differentiating Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in the Beijing family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006; 256:258–265.59. Surikova OV, Voitech DS, Kuzmicheva G, Tatkov SI, Mokrousov IV, Narvskaya OV, Rot MA, van Soolingen D, Filipenko ML. Efficient differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains of the W-Beijing family from Russia using highly polymorphic VNTR loci. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005; 20:963–974.60. Supply P, Allix C, Lesjean S, Cardoso-Oelemann M, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Willery E, Savine E, de Haas P, van Deutekom H, Roring S, et al. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 2006; 44:4498–4510.61. Iwamoto T, Yoshida S, Suzuki K, Tomita M, Fujiyama R, Tanaka N, Kawakami Y, Ito M. Hypervariable loci that enhance the discriminatory ability of newly proposed 15-loci and 24-loci variable-number tandem repeat typing method on Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains predominated by the Beijing family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007; 270:67–74.62. Oelemann MC, Diel R, Vatin V, Haas W, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Locht C, Niemann S, Supply P. Assessment of an optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive- unit-variable-number tandem-repeat typing system combined with spoligotyping for population-based molecular epidemiology studies of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007; 45:691–697.63. Alonso-Rodríguez N, Martínez-Lirola M, Herránz M, Sanchez-Benitez M, Barroso P; INDAL-TB group. Bouza E, García de Viedma D. Evaluation of the new advanced 15-loci MIRU-VNTR genotyping tool in Mycobacterium tuberculosis molecular epidemiology studies. BMC Microbiol. 2008; 8:34.64. Shamputa IC, Rigouts L, Eyongeta LA, El Aila NA, van Deun A, Salim AH, Willery E, Locht C, Supply P, Portaels F. Genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity among Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004; 42:5528–5536.65. Shamputa IC, Jugheli L, Sadradze N, Willery E, Portaels F, Supply P, Rigouts L. Mixed infection and clonal representativeness of a single sputum sample in tuberculosis patients from a penitentiary hospital in Georgia. Respir Res. 2006; 7:99.66. Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988; 26:2465–2466.67. Weniger T, Krawczyk J, Supply P, Niemann S, Harmsen D. MIRU-VNTRplus: a web tool for polyphasic genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:W326-31.68. Farber JM. An introduction to the hows and whys of molecular typing. J Food Prot. 1996; 59:1091–1101.69. Stern MJ, Ames GF, Smith NH, Robinson EC, Higgins CF. Repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences: a major component of the bacterial genome. Cell. 1984; 37:1015–1026.70. Healy M, Huong J, Bittner T, Lising M, Frye S, Raza S, Schrock R, Manry J, Renwick A, Nieto R, et al. Microbial DNA typing by automated repetitive-sequence-based PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2005; 43:199–207.71. Jang MH, Choi GE, Shin BM, Lee SH, Kim SR, Chang CL, Kim JM. Comparison of an automated repetitive sequence-based PCR microbial typing system with IS6110-restriction fragment length polymorphism for epidemiologic investigation of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Korea. Korean J Lab Med. 2011; 31:282–284.72. Niemann S, Köser CU, Gagneux S, Plinke C, Homolka S, Bignell H, Carter RJ, Cheetham RK, Cox A, Gormley NA, et al. Genomic diversity among drug sensitive and multidrug resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with identical DNA fingerprints. PLoS One. 2009; 4:e7407.73. Pettersson E, Lundeberg J, Ahmadian A. Generations of sequencing technologies. Genomics. 2009; 93:105–111.74. Kato-Maeda M, Ho C, Passarelli B, Banaei N, Grinsdale J, Flores L, Anderson J, Murray M, Rose G, Kawamura LM, et al. Use of whole genome sequencing to determine the microevolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during an outbreak. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e58235.75. Roetzer A, Diel R, Kohl TA, Rückert C, Nübel U, Blom J, Wirth T, Jaenicke S, Schuback S, Rüsch-Gerdes S, et al. Whole genome sequencing versus traditional genotyping for investigation of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreak: a longitudinal molecular epidemiological study. PLoS Med. 2013; 10:e1001387.76. Bryant JM, Schürch AC, van Deutekom H, Harris SR, de Beer JL, de Jager V, Kremer K, van Hijum SA, Siezen RJ, Borgdorff M, et al. Inferring patient to patient transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from whole genome sequencing data. BMC Infect Dis. 2013; 13:110.77. Guerra-Assunção JA, Houben RM, Crampin AC, Mzembe T, Mallard K, Coll F, Khan P, Banda L, Chiwaya A, Pereira RP, et al. Recurrence due to relapse or reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a whole-genome sequencing approach in a large, population-based cohort with a high HIV infection prevalence and active follow-up. J Infect Dis. 2015; 211:1154–1163.78. Kohl TA, Diel R, Harmsen D, Rothgänger J, Walter KM, Merker M, Weniger T, Niemann S. Whole-genome-based Mycobacterium tuberculosis surveillance: a standardized, portable, and expandable approach. J Clin Microbiol. 2014; 52:2479–2486.79. Ross BC, Raios K, Jackson K, Dwyer B. Molecular cloning of a highly repeated DNA element from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its use as an epidemiological tool. J Clin Microbiol. 1992; 30:942–946.80. Chaves F, Yang Z, el Hajj H, Alonso M, Burman WJ, Eisenach KD, Dronda F, Bates JH, Cave MD. Usefulness of the secondary probe pTBN12 in DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 1996; 34:1118–1123.81. Abed Y, Davin-Regli A, Bollet C, De Micco P. Efficient discrimination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains by 16S-23S spacer region-based random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33:1418–1420.82. Glennon M, Smith T. Can random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of the 16S-23S spacer region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis differentiate between isolates? J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33:3359–3360.83. Singh SP, Salamon H, Lahti CJ, Farid-Moyer M, Small PM. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for molecular epidemiologic and population genetic studies of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 1999; 37:1927–1931.84. Ruiz M, Rodríguez JC, Rodríguez-Valera F, Royo G. Amplified-fragment length polymorphism as a complement to IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 2003; 41:4820–4822.85. Krishnan MY, Radhakrishnan I, Joseph BV, Madhavi Latha GK, Ajay Kumar R, Mundayoor S. Combined use of amplified fragment length polymorphism and IS6110-RFLP in fingerprinting clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Kerala, South India. BMC Infect Dis. 2007; 7:86.86. Goulding JN, Stanley J, Saunders N, Arnold C. Genome-sequence-based fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Clin Microbiol. 2000; 38:1121–1126.87. Sims EJ, Goyal M, Arnold C. Experimental versus in silico fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: improved typing with an extended fragment range. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:4072–4076.88. Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant DA, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998; 95:3140–3145.89. Lu B, Dong HY, Zhao XQ, Liu ZG, Liu HC, Zhang YY, Jiang Y, Wan KL. A new multilocus sequence analysis scheme for Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Biomed Environ Sci. 2012; 25:620–629.90. Cooksey RC, Jhung MA, Yakrus MA, Butler WR, Adékambi T, Morlock GP, Williams M, Shams AM, Jensen BJ, Morey RE, et al. Multiphasic approach reveals genetic diversity of environmental and patient isolates of Mycobacterium mucogenicum and Mycobacterium phocaicum associated with an outbreak of bacteremias at a Texas hospital. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008; 74:2480–2487.91. Baker L, Brown T, Maiden MC, Drobniewski F. Silent nucleotide polymorphisms and a phylogeny for Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10:1568–1577.92. McHugh TD, Newport LE, Gillespie SH. IS6110 homologs are present in multiple copies in mycobacteria other than tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1997; 35:1769–1771.93. Barnes PF, Cave MD. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:1149–1156.94. Mulenga C, Shamputa IC, Mwakazanga D, Kapata N, Portaels F, Rigouts L. Diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes circulating in Ndola, Zambia. BMC Infect Dis. 2010; 10:177.95. Gori A, Bandera A, Marchetti G, Degli Esposti A, Catozzi L, Nardi GP, Gazzola L, Ferrario G, van Embden JD, van Soolingen D, et al. Spoligotyping and Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Emerg Infect Dis. 2005; 11:1242–1248.96. de Beer JL, van Ingen J, de Vries G, Erkens C, Sebek M, Mulder A, Sloot R, van den Brandt AM, Enaimi M, Kremer K, et al. Comparative study of IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism and variable-number tandem-repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in the Netherlands, based on a 5-year nationwide survey. J Clin Microbiol. 2013; 51:1193–1198.97. Jonsson J, Hoffner S, Berggren I, Bruchfeld J, Ghebremichael S, Pennhag A, Groenheit R. Comparison between RFLP and MIRU-VNTR genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated in Stockholm 2009 to 2011. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e95159.98. Kremer K, Au BK, Yip PC, Skuce R, Supply P, Kam KM, van Soolingen D. Use of variable-number tandem-repeat typing to differentiate Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing family isolates from Hong Kong and comparison with IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism typing and spoligotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2005; 43:314–320.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Characteristics of Molecular Strain Typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolated from Korea

- Rifampin-resistant Relapsed Tuberculosis Confirmed by Molecular Technique

- Application of Infrequent-Restriction-Site Amplification for Genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-tuberculous Mycobacterium

- The Present and Future of Molecular Epidemiology in Tuberculosis

- Molecular fingerprinting of clinical isolates of Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis from India by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)